The Curious Case Of Hybrids In Watchmaking

You certainly know about hybrids in the world of cars… But what about hybrid-based watchmaking?

Quartz and mechanical watches have learned to co-exist, but the call of nature still produces mixed offspring. If one almost killed the other, mechanical watches rose from the ashes and returned stronger than ever. However, just like the automotive world, things are changing, and the watchmaking industry has seen the arrival of new wrist-worn technologies, inventions which have nothing in common with classic watchmaking – whether we talk quartz or mechanical. Their survival is a matter of evolution, and maybe of merging… And here comes the concept of hybrid watchmaking.

Defining Hybrid

Hybrids entered our world in several areas, generating a fair amount of confusion about the definition. If you are a biologist, a hybrid would mean an offspring of two animals representing different species or varieties. A style combining two elements may be called a hybrid by a musician. In business, a hybrid would be a mix of in-office and remote work so employees have greater work-life balance and flexibility. A hybrid car would rely upon an internal combustion engine and electric motors drawing power from a battery charged through regenerative braking and by the engine. In watches, hybrid is used freely to describe several creative solutions.

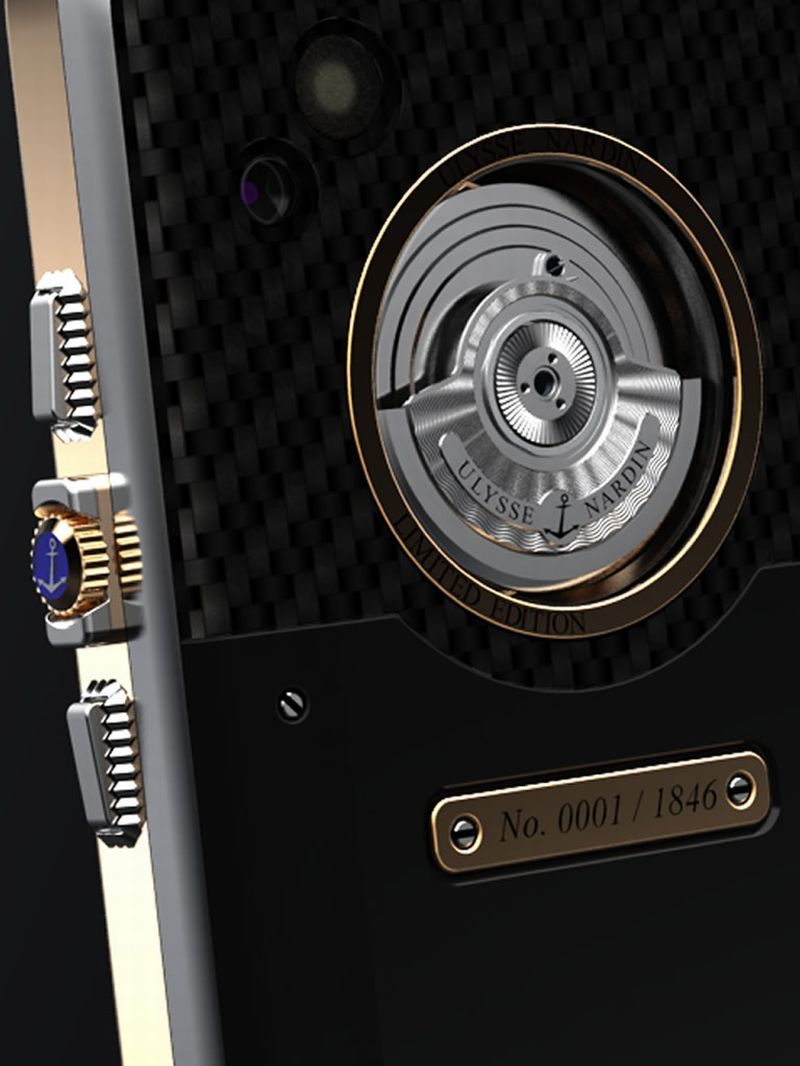

The first-generation Toyota Prius… Looking at it might explain why the idea of “hybrid” wasn’t really creating emotions If we adopt the automotive industry’s definition, a hybrid watch must be mechanical, wound manually or by a rotating weight, with a built-in battery-powered electric motor. The motor will only engage to keep the watch running once the main spring loses its torque. The battery would have to be fueled by the rotor’s movement for the experiment’s purity. (Remember the Ulysse Nardin Chairman, an Android smartphone launched in 2011? It had a rotor to charge the battery).

Creating such a hybrid watch is possible, but to what end? Purely mechanical watches offer an impressive power reserve of up to 50 days, like the Hublot MP-05 Ferrari, or 31, like the A. Lange & Söhne Lange 31, and a 7 to 10-day power reserve is becoming very common. Think Panerai Luminor GMT 10 days, Oris Big Crown ProPilot Calibre 111, or Parmigiani Kalpa Hebdomadaire. Quartz battery-powered movements can run non-stop for about four years.

But non-stop functioning is just one of the aspects to consider. Accuracy and maintaining it at a constant level is what has preoccupied watchmakers’ minds for ages – and still does. After all, quartz technology was born almost 100 years ago from a desire to exercise better control over chronometric functions. Back in 1927, Bell Telephone Labs engineer Warren Marrison discovered that he could achieve a constant uniform vibration by sending a charge through a quartz crystal. He used this observation to create a quartz mechanism, albeit the size of a room, but with much better accuracy than offered by a mechanical watch.

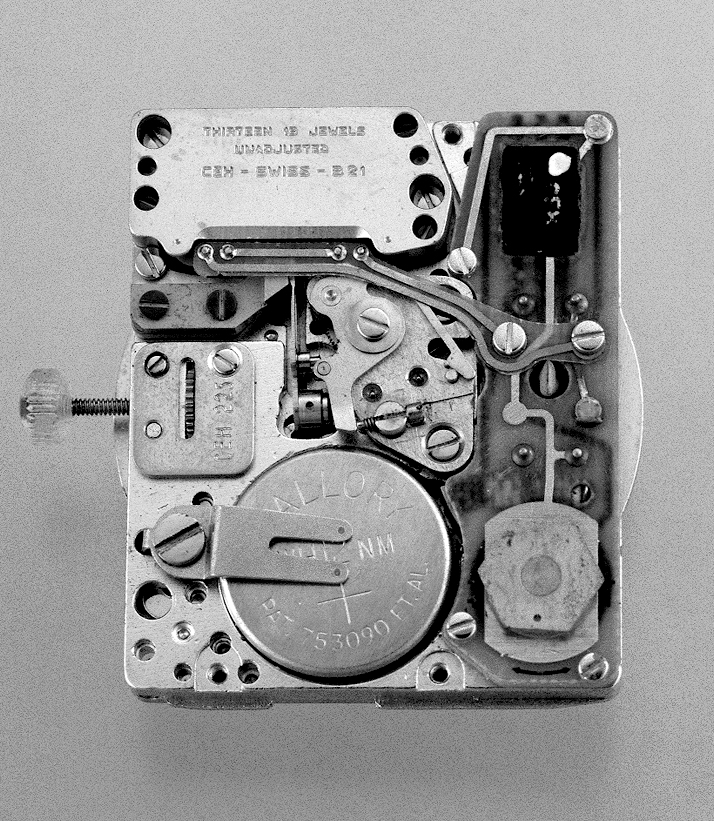

The Quartz Astron was the first serial wristwatch quartz movement and was presented by Seiko in 1969. Seiko had used quartz in chronometry for many years, producing large clocks for astronomical observatories. Then these devices were reduced to the size of table clocks, and it became evident that quartz technology would eventually be applied to wristwatches and that the Swiss and Japanese would compete. At Seiko, they tasked a group of engineers from within the company while the Swiss formed a committee. This committee recruited engineers from several competing watch brands, scientists, and employees of electronics companies. The group of specialists settled in Neuchâtel was named Center Electronique Horloger (CEH). By 1967 CEH had produced the world’s first quartz movement Beta 21 but in a microscopic series with only five prototypes.

Although Japan was ahead of its Swiss counterparts in the development of mass-production quartz, Patek, Rolex and Audemars Piguet soon presented their watches that used Swiss-made quartz movements. The first quartz watches were expensive – Seiko’s Quartz Astron, they say, cost as much as a car. But the technology developed, the consumers appreciated it, and off we went. Mass production of inexpensive quartz watches flooded the market, almost killing the mechanical watch industry in Switzerland. In the same year, 1969, Seiko, ahead of the Swiss, released its automatic chronograph movement – the company was and still is one of the most advanced in quartz and mechanical movements. So it was no surprise that Seiko offered a way to control a mechanical movement using a new regulating organ. Enter Seiko Spring Drive, a hybrid defined by a musician’s approach involving a combination of two elements.

Hybrid According to Grand Seiko, The Spring Drive

Seiko/Grand Seiko first presented the Spring Drive movement in 1998, following two decades of research and development and over six hundred prototypes. Yoshikazu Akahane, an engineer at the Suwa Seikoshi watchmaking branch, is said to have been inspired by the use of bicycle brakes to maintain constant speed during the hill descent. Akahane thought to apply the same principle to the motion control of watch hands without using a balance wheel, and it is, in essence, the foundation of the Spring Drive movements.

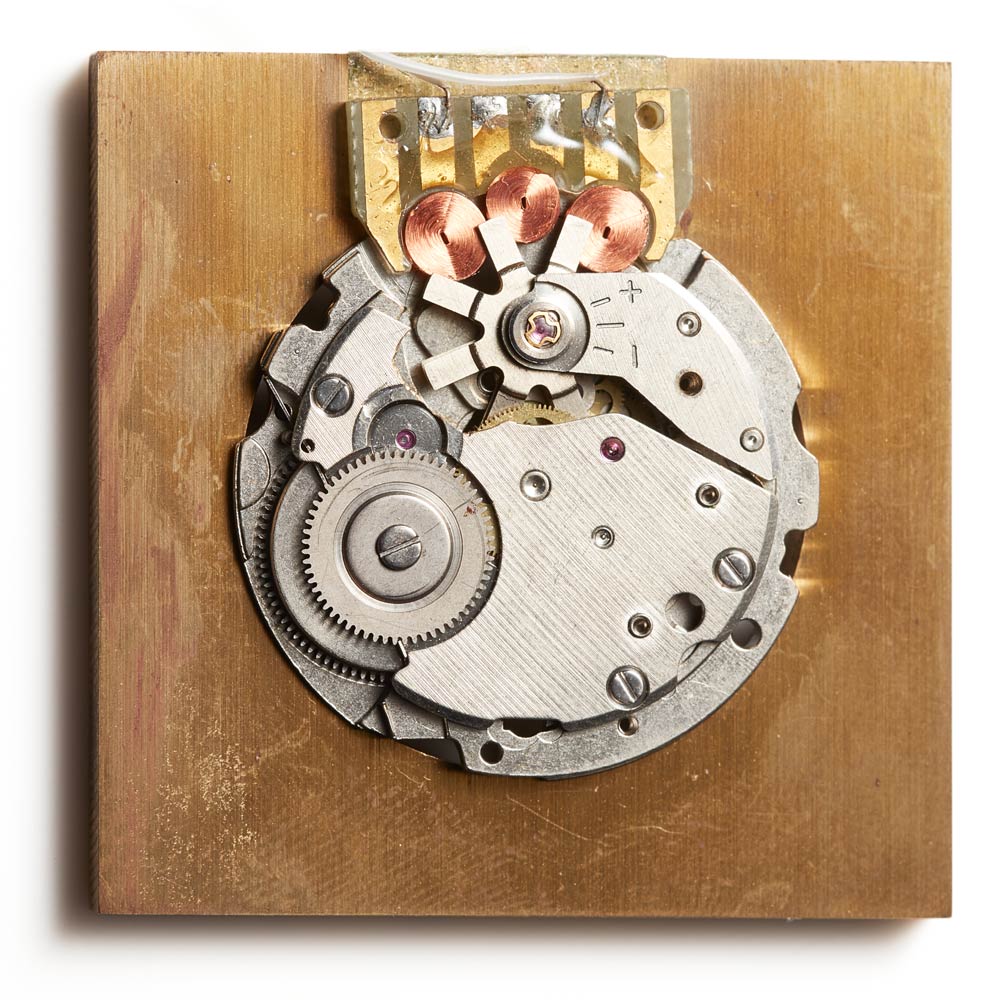

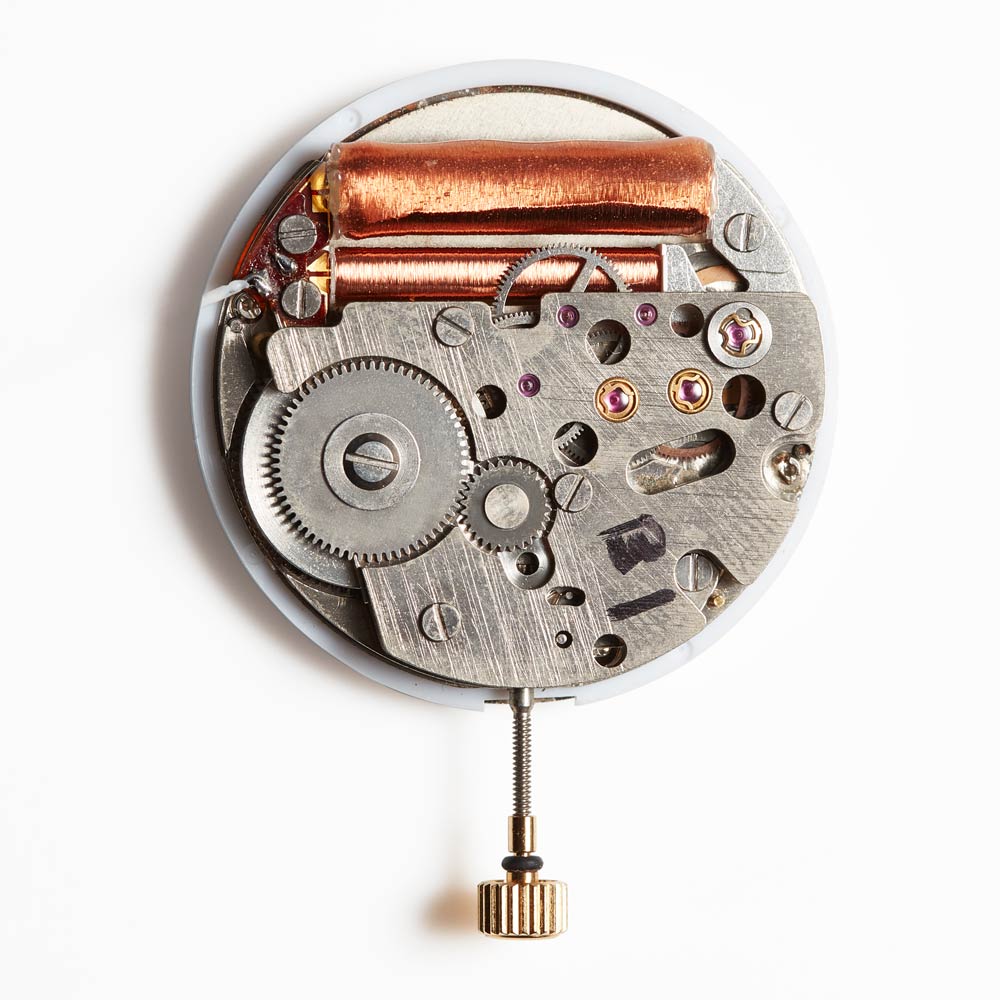

Below: The first Spring Drive prototype from 1982 (left) and the second Spring Drive prototype from 1993 (right). Images from Grand Seiko

Like a regular mechanical watch movement, a Spring Drive calibre is powered by a mainspring. The energy is then transferred to the gear train, making the watch hands move in the desired manner. The absence of the escapement and the balance wheel is the main difference between the two movements, as the Spring Drive uses a regulator that manages three different types of energy (Tri-synchro Regulator). It is mechanical from the mainspring, electrical converted from mechanical to power up the quartz oscillator and electromagnetic for the variable “braking” – adjustment of the rotational speed of the hands.

In 1999, the first commercial models equipped with Spring Drive movements – 7R68 and 7R78 – were launched exclusively for the Japanese market as limited editions. The company produced two references under the Seiko brand in steel and gold cases and a Credor in platinum. These were manually wound movements with a power reserve of 48 hours. In 2004, the 9R65 automatic calibre debuted, with a power reserve of 72 hours. The Spring Drive made its way to Grand Seiko-branded watches with the release of SBGA001, and in 2007, the Grand Seiko Spring Drive chronograph was introduced. Today, the 9R Spring Drive movement family comprises 11 calibres, with chronograph and GMT functions, 3 to 8 days power reserve, all accurate to +/- 0.5 or 1.0 seconds per day.

Good work, Japan, but what about Switzerland? There were quite a few patents on the subject registered in the 1970s, like the ? 595636 by Ebauches SA, for a “watch movement driven by a spring and regulated by an electronic circuit“, but to my knowledge, nothing materialised. My guess is that the Swiss had a vote and were not in favour of developing a local Spring Drive competitor. However, the idea of a hybrid, whatever the definition, Spring Drive-like or not, keeps on popping up, and there are some exciting models to mention.

Piaget Enters the Hybrid Scene

The closest to the Spring Drive would be the Piaget Emperador Coussin XL 700P, which took many of us by surprise in 2016. Although Piaget was active in the Beta 21 project and developed a Swiss quartz wristwatch and other refined quartz movements, we cherish the brand for its mechanical prowess.

With all the expertise in mechanical and quartz technologies, Piaget’s 700P was an engineering exercise and proof of its capabilities. It was modelled after the Piaget Polo Emperador Tourbillon and had an attractive appearance; only a generator occupied the space of the tourbillon. The Piaget Emperador Coussin XL 700P was an exquisite high-end timepiece with a micro-rotor on the dial side to power up the mainspring. The energy from the mainspring was released to drive a gear train, which transferred power to an alternator to generate an electric current. This energy powered the quartz oscillator, which controlled the alternator’s 5.33 rotations per second.

As in the Spring Drive, a “braking system” was developed to bring the oscillations down to 32Hz. The 700P was accurate to +/- 1 second per day, way beyond the reach of any mechanical calibre without electronic assistance. What is the main difference between the 700P and the Spring Drive? Well, the Spring Drive movements are in the wild, alive and ticking; the 700P is as if it never existed. In conclusion, the 700P deserves a place in the biological hybrids section as the offspring of two animals representing different species that did not survive the evolution process. RIP.

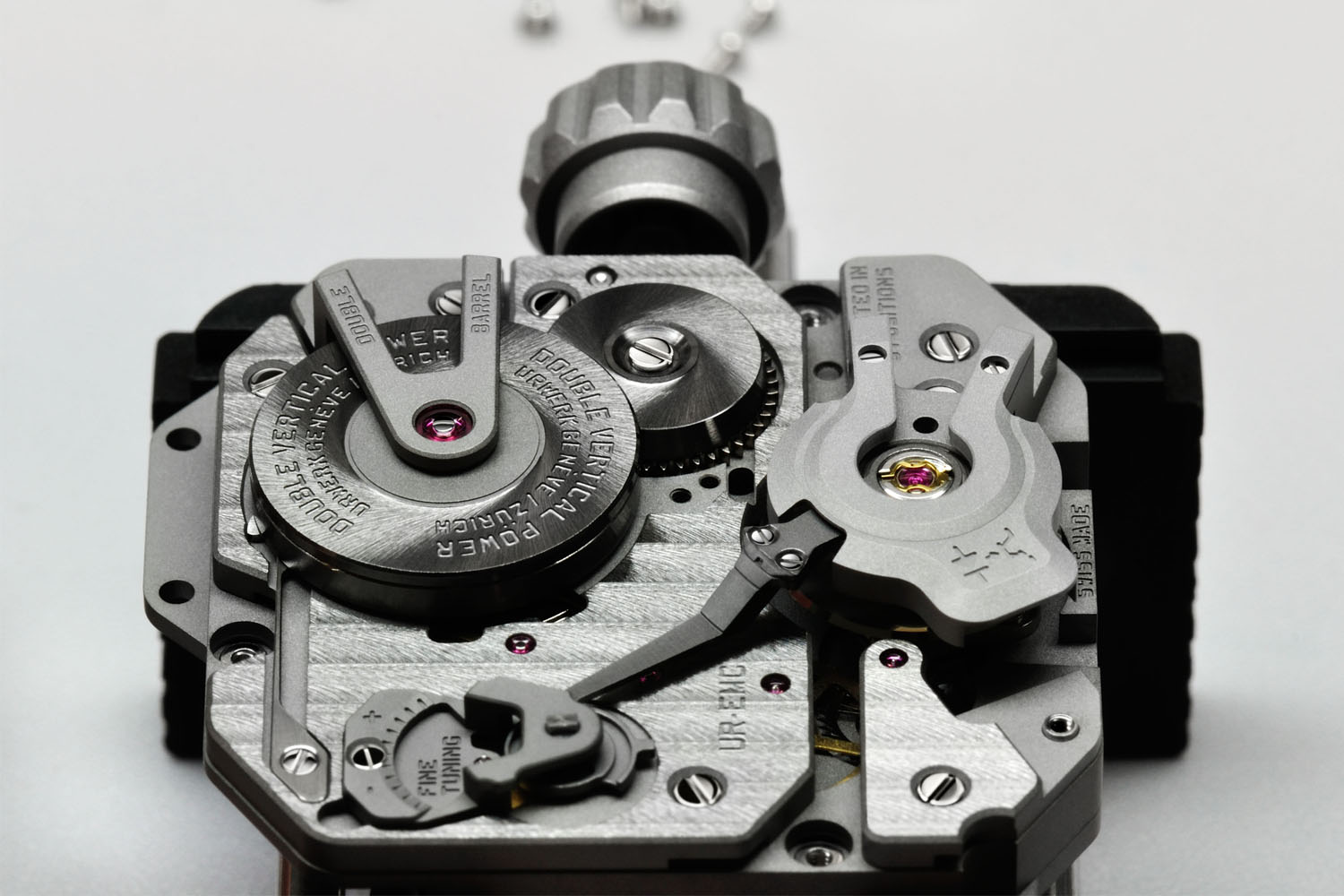

Hybrid of a different kind, The Urwerk EMC

The quest for accuracy and the inspiration to learn how an owner interacts with a watch led Martin Frei and Felix Baumgartner at Urwerk to another, different sort of hybrid creation, an EMC – Electro Mechanical Control. The Urwerk EMC is a mechanical watch with some electronics inside to measure chronometric performance and report it to the owner.

The optical sensor, mounted on the balance wheel, registers the oscillation rate. This sensor is connected to an electronic oscillator that serves as a reference, and the circuit board calculates the difference between the going rate and the reference rate. A precision indicator on the dial side, with +/-20seconds per day range, informs the owner of the Urwerk EMC whether a tune-up is needed. The fun part? If the watch’s accuracy is off, the owner does not need to take his mechanical wonder to a watchmaker. A fine adjustment can be performed by turning the designated screw on the back of the watch. It saves time, and money, too. Mind you, no batteries, just a micro-generator with a giant winding handle to power it up.

The Urwerk EMC was revealed as a working piece in 2013; five years later, another exciting Urwerk model named AMC proved once again that Baumgartner/Frei’s creative spirit has no limits. Modelled after Breguet’s “Sympathique” clocks with a built-in system that allowed a pocket watch to be automatically set and wound when put in the special compartment of the table clock, the contemporary version offered to set the wristwatch with atomic precision – deviation of one second in 317 years. The AMC base (mother clock) can wind, adjust and regulate the wristwatch, and all operations are mechanical and performed by pins and triggers. But I digress.

Frederique Constant Brings “Smart” into Mechanical

In 2018 Frederique Constant presented a watch that put the concept of hybrid in the spotlight, on the dial and inside the case. The Frederique Constant Hybrid Manufacture featured a combination of mechanical and digital – its “best of both worlds” solution. The mechanical part came dressed as a manufactured FC-750 calibre; the first FC movement developed in-house. The digital part was an intelligent module created by sister company MMT (Manufacture Modules Technologies), installed on top of the mechanical calibre.

The watch retained the aesthetic and emotional appeal of a classic timepiece, as well as the implied Swiss-made value, and at the same time, it received relevant smart functions. Activity tracking and sleep monitoring were useful features accessible via the Hybrid App. But it was the possibility to run diagnostics on the watch, to check its health, that really mattered. The diagnostic function measured rate, amplitude and beat daily and made the report available in the app.

To some extent, Frederique Constant and MTT followed the path set by the Urwerk EMC, but in the case of EMC, the owner could make the necessary adjustment should the test reveal anomalies. With Frederique Constant’s Hybrid Manufacture, the watch would have to be taken to the service centre, which makes all the difference. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a system to perform the necessary mechanical movement tune-up autonomously? The idea has a certain appeal, but no matter how ingenious, such a device will take away all the fun of owning a mechanical timepiece.

Conclusion

To bring this long review to a logical end and in search of a proper definition, let us consult the Internet. The web explains that a hybrid watch is any watch that looks like a traditional, classic analogue watch but functions as a smartwatch. I think these are hideous beasts, but with sales growing exponentially, I am a minority. We all champion the creativity, research, engineering and production efforts of those tasked voluntarily – or by obligation – to seek the best of both worlds, but let’s face it, the pure mechanical breed remains the most attractive, with all its flaws. So be it. (And since you’re reading MONOCHROME, you must have been expecting this answer!).

14 responses

Beta 21 wasn´t the first quartz watch, but Beta 1, that competed at the observatory competitions in 1967.

You’ve left out the Ressence Type 2, also a hybrid of source with it’s e-crown and solar capabilities!

I love Spring Drive and my two SD watches perform pretty well for several years already.

Thanks for the article!!

No mention of mechaquartz ie Seiko’s VK series example VK64

You say, “The 700P was accurate to +/- 1 second per day, way beyond the reach of any mechanical calibre without electronic assistance.” But that is a two second window of accuracy per day for the 700P – exactly what the new purely mechanical Omega caliber claims at 0 to +2 per day. Your statement then is hyperbolic at best and misleading at worst.

you almost got a balance here in the article away from promotion of a spring drive, almost.

omitting so many important hybrid developments that could have made a quality article of this quick post.

Interesting topic, a more in-depth look would be even better. In particular, I wonder how Spring Drive will compare with the new Omega Spirate technology going forward, and what this means for “hybrid” movements.

The first electromechanical watch was the Salto in 1997, by Asulab, the research center of the Swatch Group.

@LusophoneLover

Regarding accuracy there’s no contest. Spring Drive doesn’t have any deviation from different positions and power status.

Swatch group introduced auto quartz with Tissot

@JJ The Omega calibre didn’t exist when the 700p was developed so the author is neither misleading nor hyperbolic.

Prior to the Spring Drive, wouldn’t Seiko’s Kinetic movements qualify as a hybrid?

@George

Hybrid, yes, but of a different kind. Kinetic is quartz, Spring Drive is mechanical movement with quartz circuit control.