When BMW Exploited A Loophole To Beat Porsche

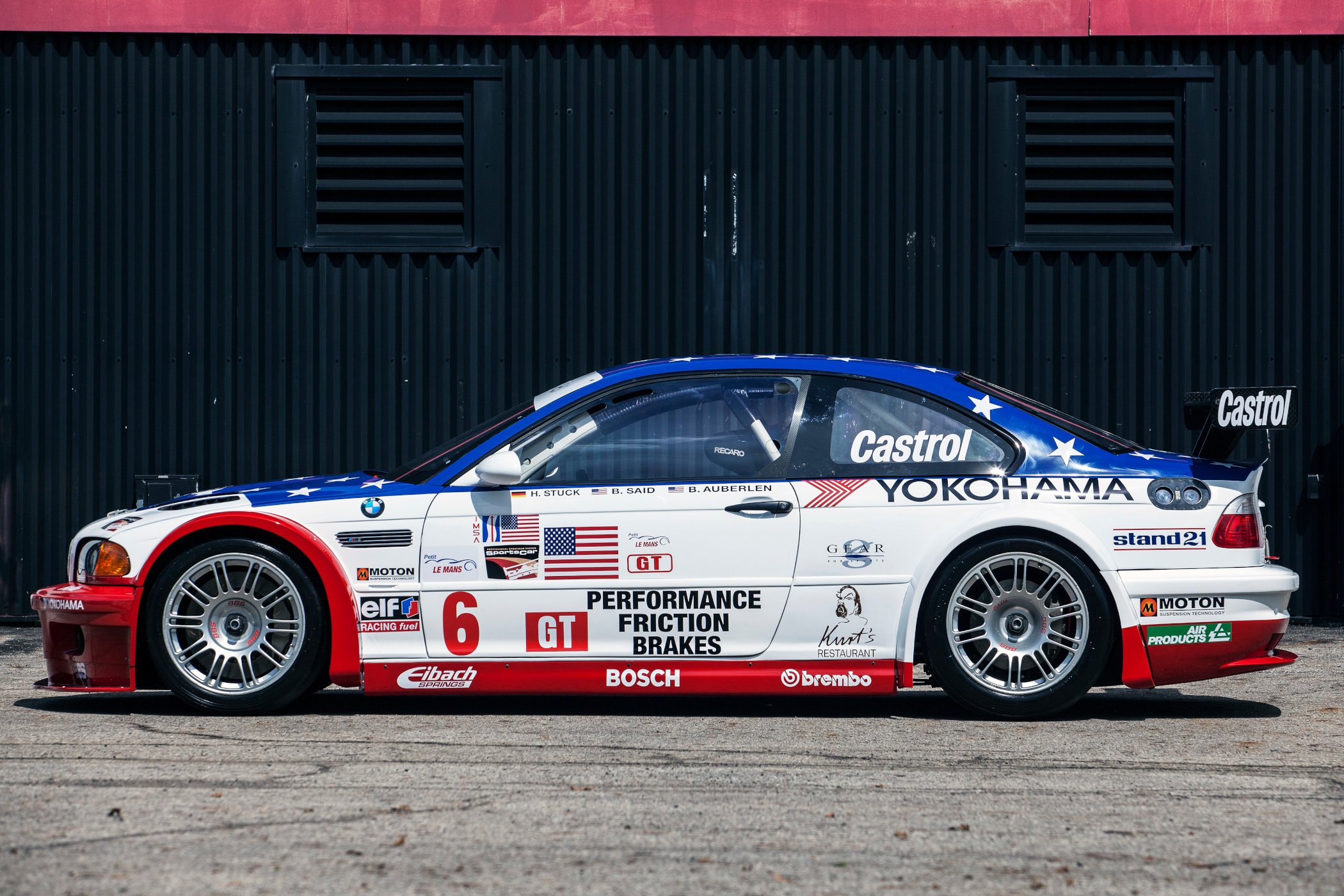

This is the story of the very special BMW E46 M3 GTR, a car that shouldn't exist, but does!

Rivalries can be a great thing, and push competitors (or even colleagues, if an internal rivalry is concerned) to great heights. This has always been the case, especially in the field of professional sports. It’s said that the first motor race was held 5 minutes after the second car got built, which paints a pretty imaginative picture of things. Rivalries will always be a part of racing, as that is the very nature of the sport; multiple cars and drivers find out who’s best on track. Racing fans still revel in the battles between Ford and Ferrari for Le Mans dominance in the early 1960s, or the Senna vs Prost rivalry! And whenever a team asserts its authority for a couple of years on end, others try to find a competitive advantage, sometimes breaking the rules in the process. But, reading the rulebook carefully, can also reveal a loophole to be exploited to gain the upper hand. One such instance was the BMW versus Porsche battle in the American Le Mans Series in the early 2000s!

Now, to make one thing clear, finding a loophole in the regulation is not necessarily breaking them. There are plenty of examples in racing history where a loophole found by one team, gave them such an advantage the team became virtually unbeatable. One of the most recent and most fitting examples is the story of Brawn GP, and the double diffuser they developed. It allowed them to pull out a very big gap during the first half of the 2009 Formula 1 season, the only year the team was active. It resulted in both the Driver’s and Constructor’s titles for the team, something that was never done before. There are also instances where drivers, constructors or teams blatantly cheated, something we’ve also covered before. But this story isn’t about cheating, but rather about interpreting the rulebook in your favour.

ALMS Racing Series

The American Le Mans Series, or ALMS in short, was created by US businessman Don Panoz in collaboration with the Le Mans organiser Automobile Club de l’Ouest. The idea was to have an endurance championship hosted on continental US soil, in the same spirit as Le Mans for prototype and GT racing cars. It ran between 1998 and 2013 and merged with Grand-Am Road Racing and would form the IMSA SportsCar Championship under the management of The International Motor Sports Association. The ruleset for ALMS was very similar to the 24 hours of Le Mans, with the exception of the length of the race. You were mandated to run a car with multiple drives under either the purpose-built prototype racing cars or modified production sports cars.

The ALMS championship made its debut with 8 races held in 1999, starting with the 12 hours of Sebring. This challenging race was held at the former Hendricks Army Airfield World War II base in Sebring, Florida. This race and track has a history dating as far back as 1950 and has become one of the most respected endurance racing events on the calendar. The championship grew to 12 races by the year 2000, and even crossed oceans to host a race in Australia and two in Europe. Where at first oval tracks and infields were used, the series moved to road courses more and more. Tracks like Laguna Seca, Road Atlanta, Mosport Park and even temporary street circuits in city centres were added to the calendar.

Just like the European counterpart, the World Endurance Championship (WEC), it attracted mainstream manufacturers and professional racing teams to the top-tier LMP1 and GTE-Pro classes. Many of the cars that lined up on the grid of the Le Mans 24 hours would also race in the ALMS championship. Manufacturers like Porsche, Audi, BMW, Chevrolet and others would enter, and even famous racing institutes like Joest and Lola would have a go (and succeed!) at winning some races and titles. One of the most notable episodes of racing under the ALMS regulations was the 2001 and 2002 seasons. This is the period where BMW tried to break Porsche’s stranglehold on GT-racing, by building a car that essentially shouldn’t have existed; the BMW E46 M3 GTR.

Porsche vs BMW, BMW vs Porsche

Ever since the early days of the brand, Porsche has a very active and hugely successful racing division. Whether it’s in Formula 1, endurance racing, GT racing, road racing or even off-roading events, Porsche is always a force to be reckoned with. This is exemplified by no less than 19 overall Le Mans 24-hour victories, more than any other manufacturer ever. At one point they even won SEVEN years in a row, and in the 1983 edition of the famous endurance race, the team even managed to lock down the entire top 10 with the exception of 9th place! But that’s only in prototype or Group C racing only and doesn’t include the countless entries and wins in other forms of racing with cars like the 906, 908, 917, 935, 956/962 and many, many others.

Another German manufacturer that’s been very successful in racing is BMW, primarily known for its multiple GT or Touring car championships. It was also active in Formula 1 and even won Le Mans as a factory racing team in 1999 with its V12 LMR. But, most people with probably think of BMW and its M3, a car that shaped touring car racing throughout Europe. And it’s this M3 that is the starting point of a very fierce rivalry in the ALMS racing series in the early 200s.

The ALMS racing series was another championship where Porsche proved its expertise and won multiple times in the early stages of the series. The LMP1 class might have been dominated by the Audi R8, but Porsche ruled the GT classes pretty much every year. In 1999 and 2000, the Zuffenhausen-based manufacturer won three out of the four GT-class titles as a manufacturer despite competition from plenty of other high-profile teams and manufacturers. One such team was BMW, who had enough of Porsche’s stranglehold after the 2000 season. So, exploiting a very particular stipulation in the regulations, it decided to up the ante and introduce a car that technically, should not have been allowed to compete; the BMW E36 M3 GTR.

The BMW E46 M3 GTR

It’s well known that for most its life, at least the first generations, the top-tier BMW 3-series was powered by a straight-six engine. This was also used in racing, as many of the classes the M3 competed in stipulated that a specific number of road-legal versions had to be built and sold to the public. Plenty of cars have started out like such so-called Homologation Specials, including very special machines like the Toyota GT-One and the Porsche 911 GT1 Strassenversion. On a lower end of the scale, special cars like the Peugeot 205 GTI and indeed the BMW E30 M3 are the result of rules like this.

But however potent and reliable the straight-six was in the M3, it proved no match for the 996-generation of the Porsche 911 GT3. So in an effort to tip the scales in their favour, BMW started development of the M3 GTR, built around a V8 engine instead. This new all-aluminium engine was specially developed for motorsports and had a 4.0-litre capacity and a power output of around 500 horsepower, much more than the straight-six it replaced. To comply with the regulations, BMW announced ten Strassenversions, or street-versions of the M3 GTR would be built using a de-tuned specimen of the race-bred 4.0 litre V8. The price for the car was set at a staggering EUR 250,000 (almost as much as the Ferrari 550 Barchetta Pininfarina of the same year!)

The car made its debut at the 12 hours of Sebring, the 2001 season-opener, but wasn’t successful straight out of the box. It won its first race in the third round of the championship, and took home a total of seven consecutive GT wins and both the Driver’s and Constructor’s title that year. This rubbed Porsche the wrong way as they argued that the BMW E46 M3 GTR was basically a prototype racer developed to compete in GT-racing. And they had a fair point, as prior to that there was never a production M3 that featured a V8 whatsoever. BMW countered by saying they complied with the rules by building a road-legal version available to the public. You can hear the commentators talk about the controversy leading into the 2001 Sonoma race below.

Nevertheless, the ALMS governing bodies took action and tightened the rules for the following year. For the 2002 season, it was stipulated that any competitor racing in the GT classes had to enter with a car that had a homologated run of 100 complete road cars, and 1,000 engines. This was no issue for Porsche whatsoever, but for BMW it was impossible to comply with such an expensive and specialist engine. That sealed the M3 GTR’s faith in the ALMS racing series, but the car would go on to win the Nürburgring 24 Hours race twice. As for the road car, sources say between 6 and 10 were built and some even suggest none were ever sold, which only adds to the unicorn status of the formidable BMW E46 M3 GTR.

For more information, please visit BMW-M.com, Press.BMWGroup.com or UltimateCarPage.com.

Editorial Note: The images portrayed in this article are sourced from Press.BMWGroup.com (red, white & blue #6 racing car & M3 GTR Strassenversion), DoubleApex.co.za and previous articles.