Deconstructing a Miyota 9015 Automatic, and What I Discovered

While I'm no watchmaker, I was curious to see how one of the industry's most widespread movements is built, and finished!

Whenever movements are discussed, attention tends to focus on the Swiss, which is understandable, but it excludes some of the biggest movement manufacturers. Seiko, Miyota and so on, let alone the Chinese, produce far more movements per year on their own than ETA or Sellita do, for instance. To put this into some form of perspective, Miyota produces three movements per second! What is also mind-boggling is that Miyota holds a Guinness World Record with its quartz calibre 2035, of which it produced a staggering 1.7 BILLION units by the late 1990s. It is still in production today and has well surpassed a total production volume of 5 billion in its 40+ year life. With all this in mind, and with the opportunity to take apart a Miyota 9015, I’m taking a stand for a movement that has become a true cornerstone of the industry and tearing one down in the process to take a closer look.

Miyota’s Mechanical lineage

As part of the Citizen Group, Miyota is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of movements. They produce both quartz and mechanical movements at an astonishing rate. The origins of Miyota date back to 1959, when Citizen built a movement factory in Miyota town, in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. It became a stand-alone name in 1980 and produces quartz and mechanical movements for the Citizen Group and third parties. And with close to 70 years of experience, Miyota has become a true expert! The company’s main factory, now located in Saku, Japan, employs just over 200 people and features an almost fully automated production and assembly line for solar, quartz, and mechanical movements.

Miyota is also known for several innovations in movement construction, including the Parashock shock-absorber system and AO-Oil and AO-Grease, long-lasting, corrosion-resistant lubricants. The movements are also entirely produced in-house, even down to the mainspring and hairspring, which should be pleasing to many. It means every step in its production is optimised and controlled, which is reassuring.

Miyota’s mechanical movement catalogue is split between the 6T-, 8000- and 9000-series of calibres. The 6T-series is where Miyota’s mechanical watchmaking journey started, back in 1969. This was followed by Calibre 82 in 1975, which became one of the most widespread mechanical movements in history. This further developed into the 8205 automatic, introduced in 1986, and eventually into the calibre 9015, launched in 2009. And Miyota doesn’t end there: in 2017, it introduced the calibre 8315, which offered a longer power reserve, and in 2021, the calibre 9075, an automatic flyer GMT movement.

To break things down even further, the 6T-series is a family of small-dimension calibres, with a width of 8 3/4 lignes (19.74mm). The 8000-series is a range of full-size mechanical movements with a standard level of finishing, while the 9000-series is the premium line based on the same architecture as the 8000-series. There are some technical differences, though, such as the capability to be wound by hand and a higher frequency for the 9000-series. The 9000-series is also slimmer and uses a different ball bearing for the central rotor to reduce noise and increase stability.

They both offer a range of functionality, from time-only displays to full calendar views, and from open-heart layouts to fully skeletonised. Depending on the specific movement within the 8000- and 9000-series, the size is either 11 1/2 lignes (25.94mm) or 13 1/2 lignes (30.45mm). That means they are within the industry’s standards, making them a solid alternative to Swiss-made counterparts (ETA 2824 or Sellita SW200).

Now, let’s move to actually taking apart one of their movements!

The Breakdown

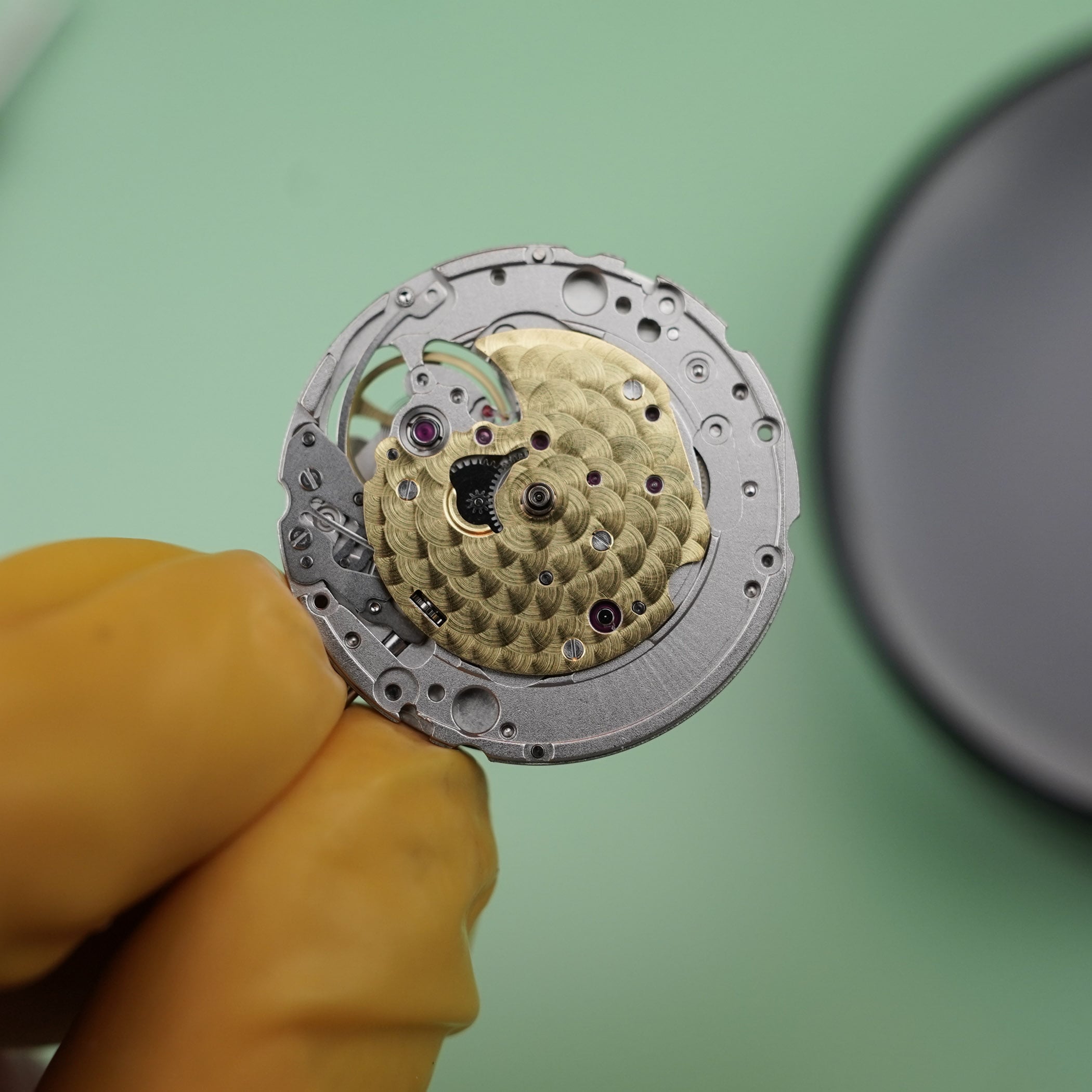

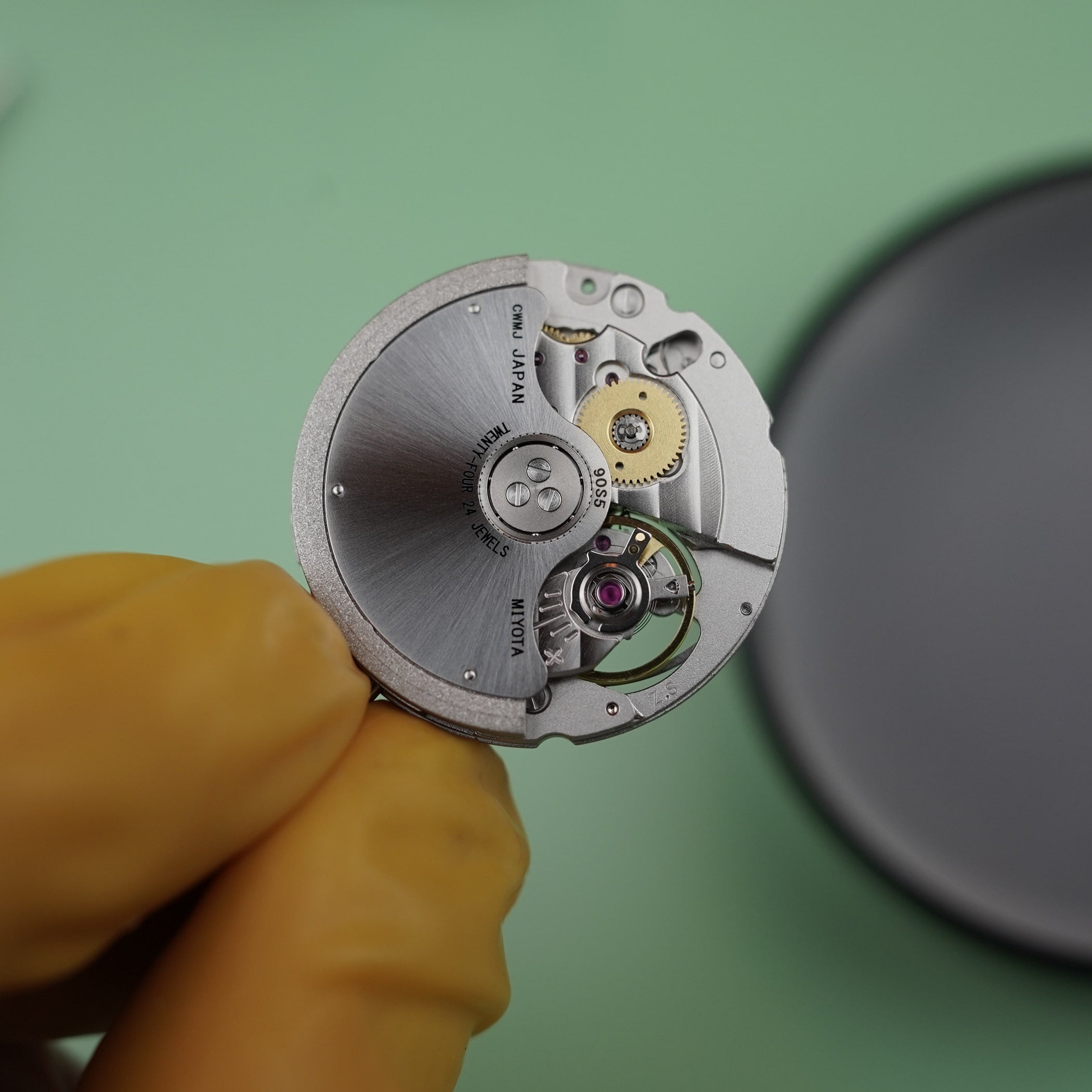

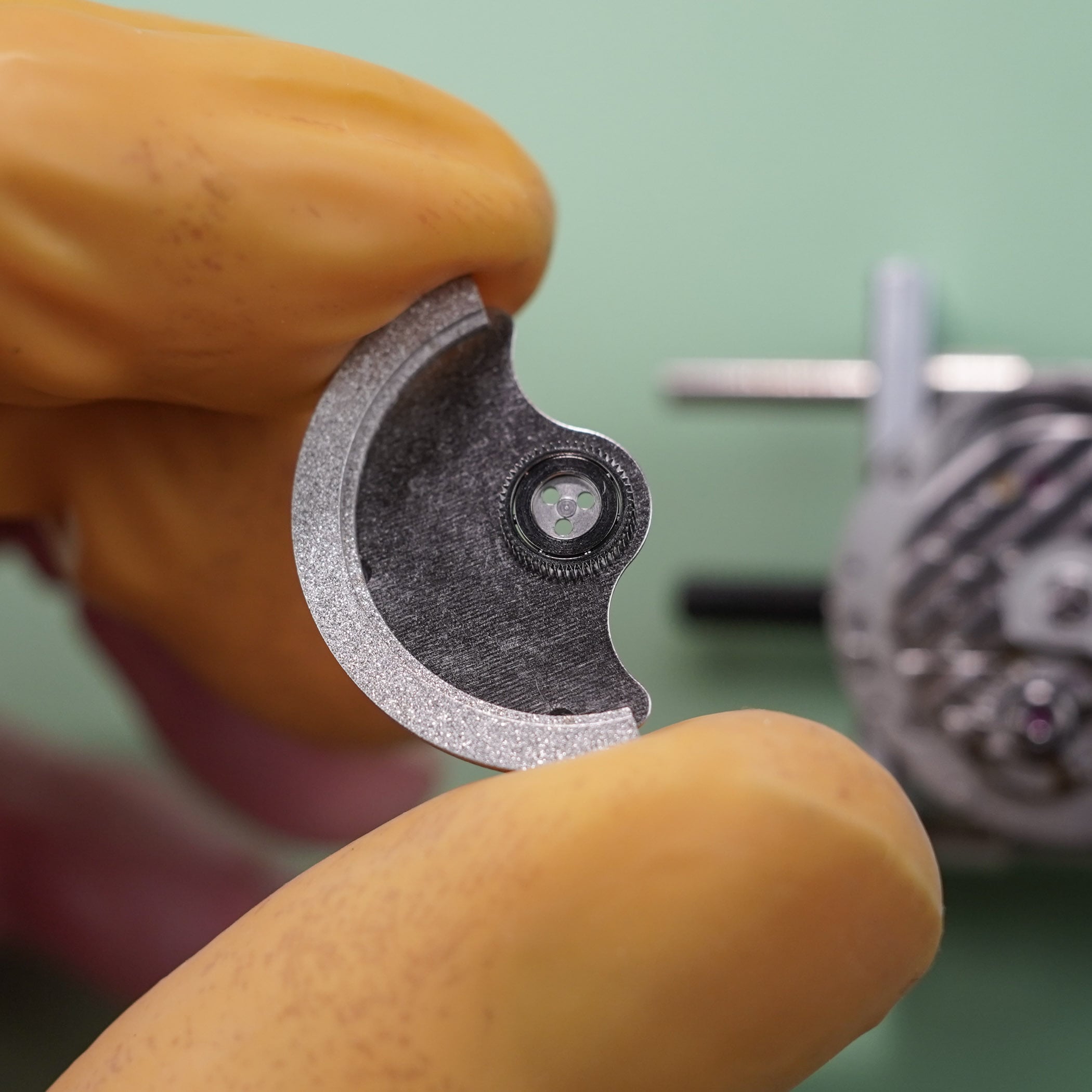

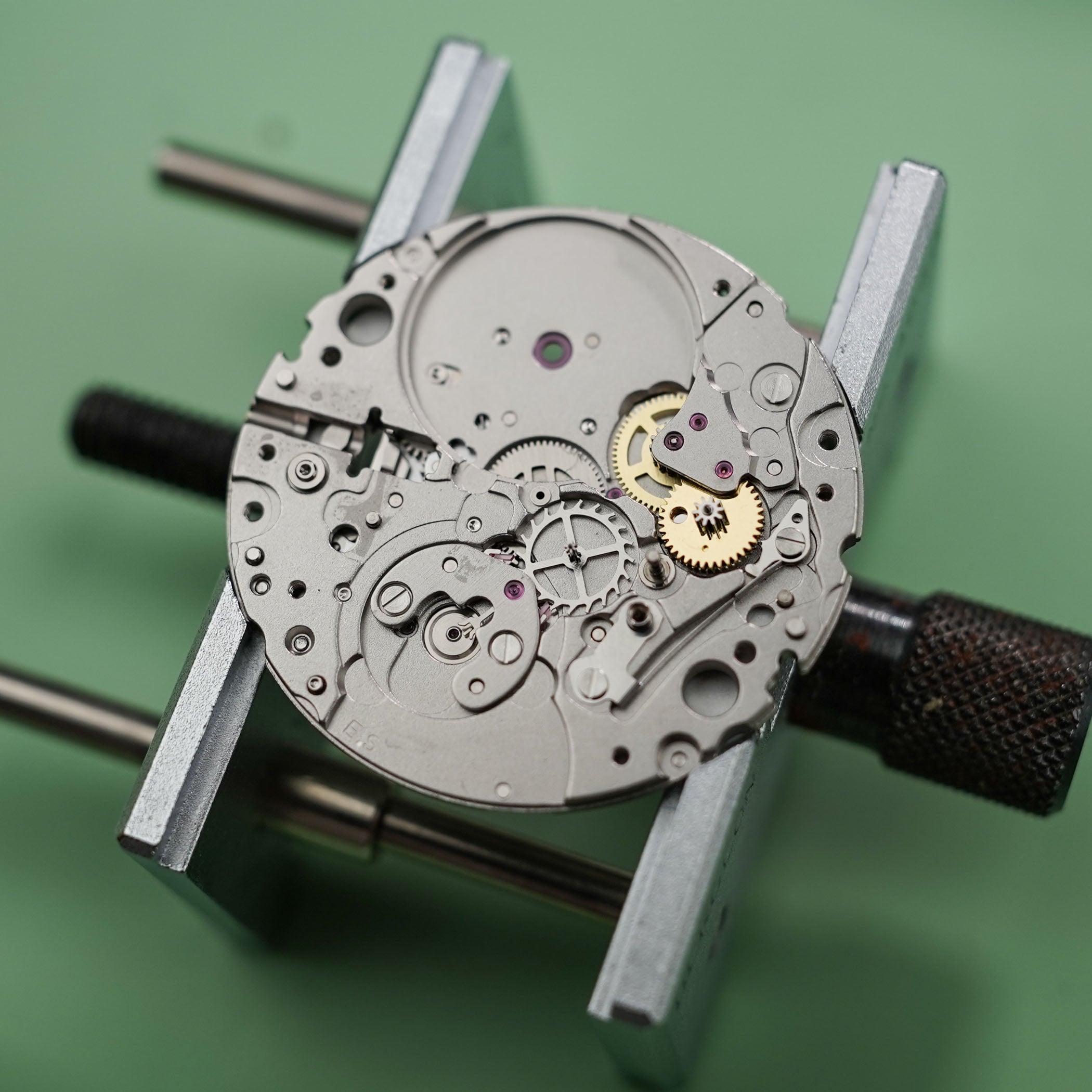

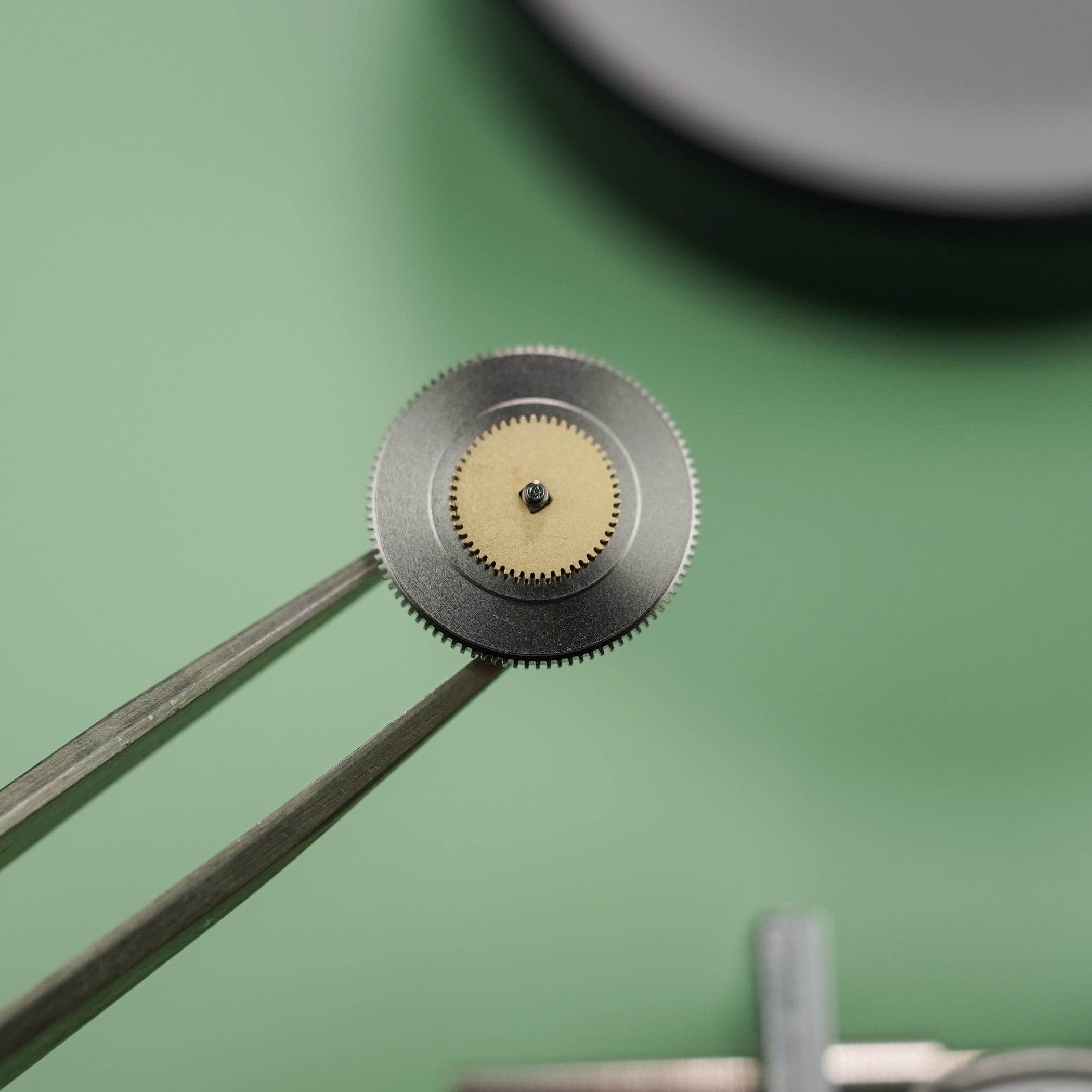

Dismantling the movement starts with removing the crown stem, and then the central rotor, which is held in place with three screws and a central ball bearing. What immediately strikes me is the difference with some of the other staples in the industry, like the ETA 2824 and Sellita SW200, which both have a single central screw.

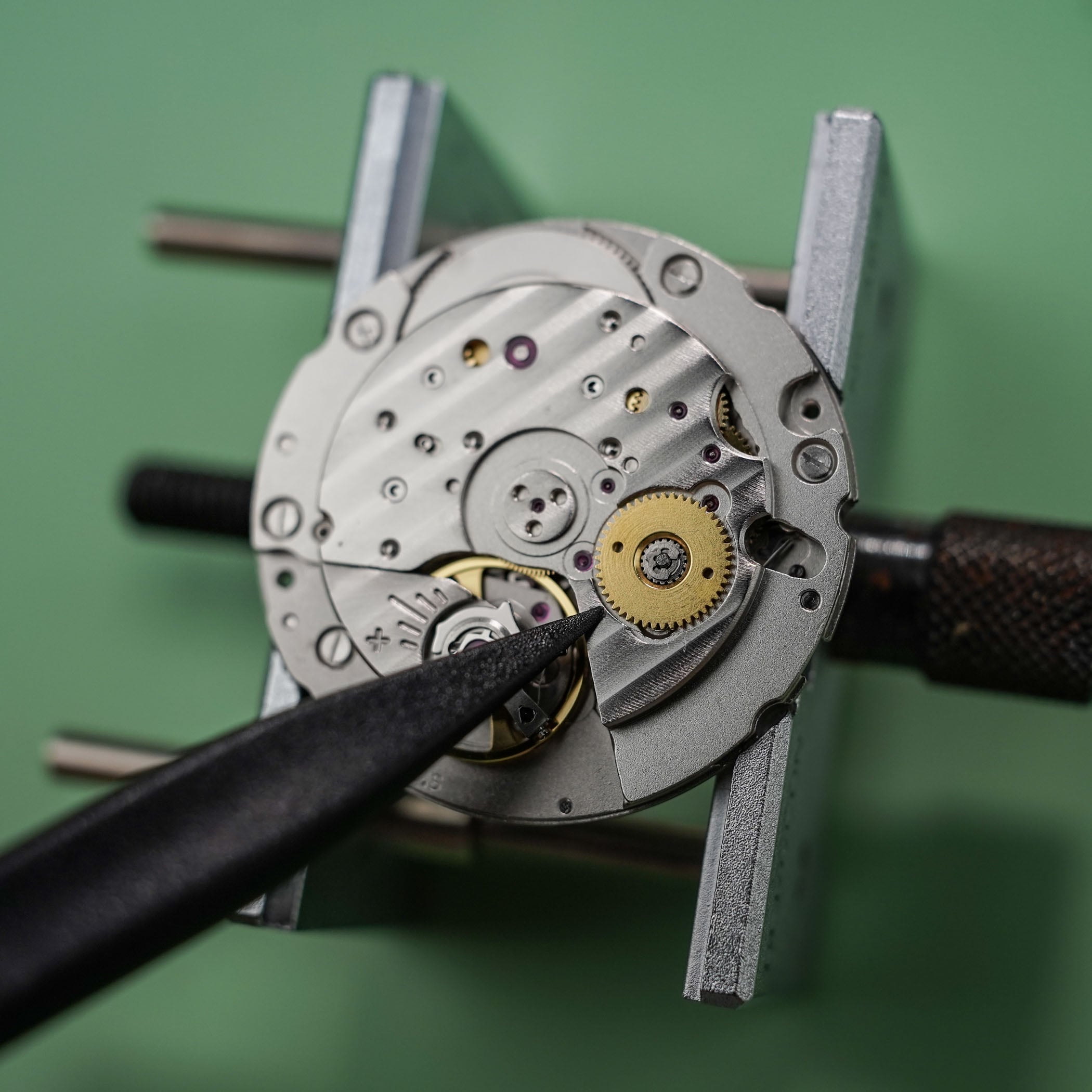

Underneath, you can notice a single directional wheel for the winding system, as opposed to the bi-directional double-wheel system in the aforementioned ETA and Sellita calibres. This means the movement is wound only in one direction as the rotor spins. When running in the other direction, it spins freely, which is why MB&F opted to use it in the M.A.D.1, for instance.

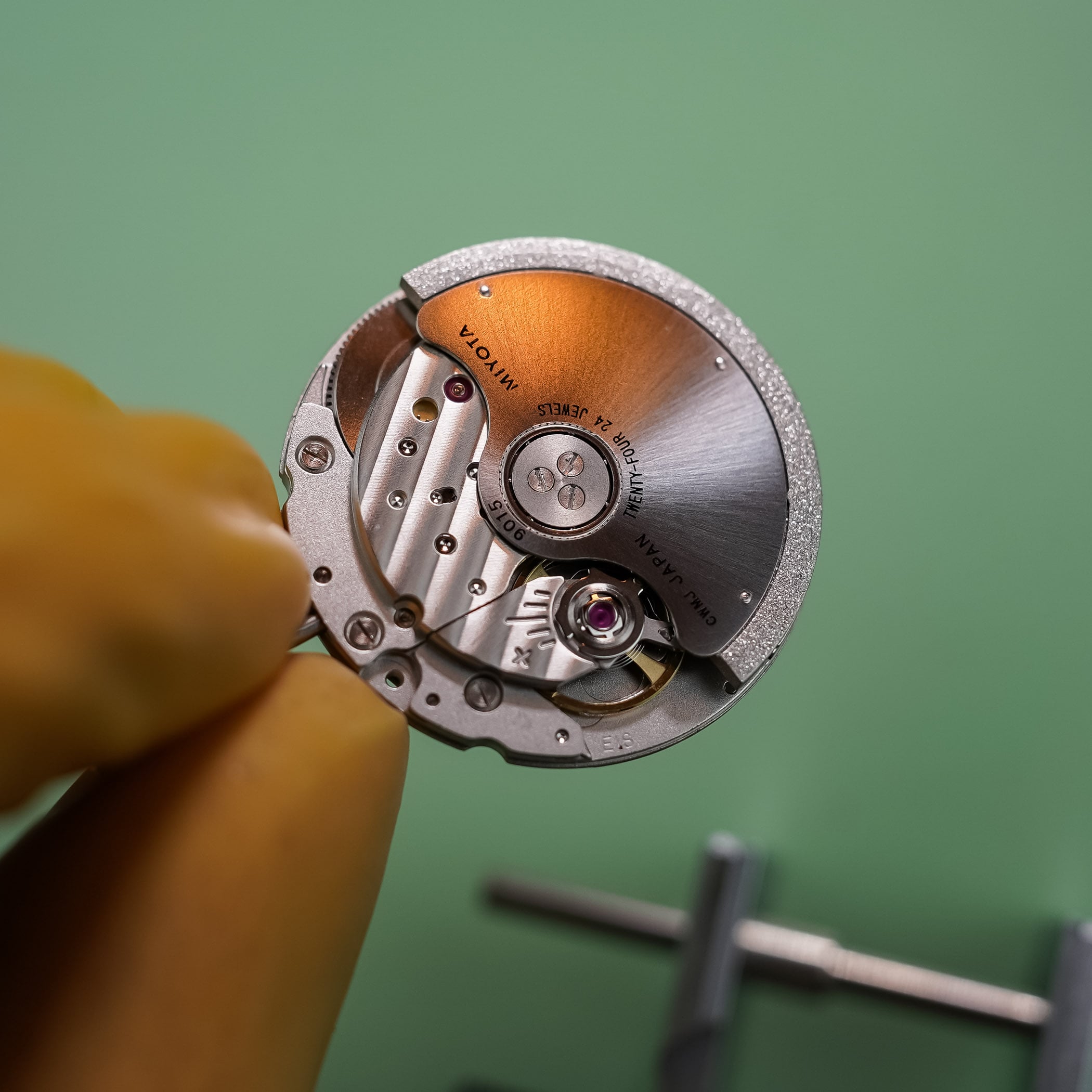

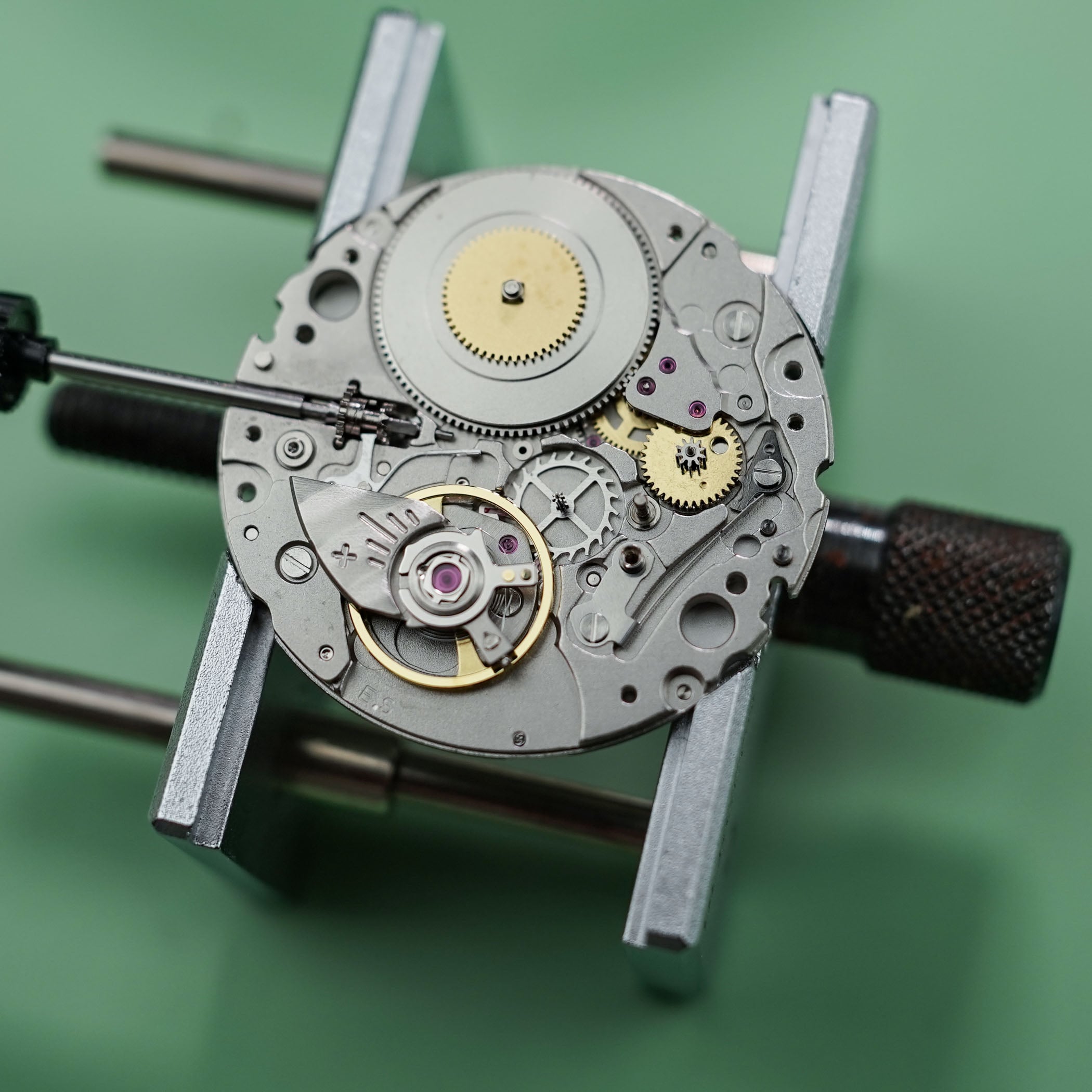

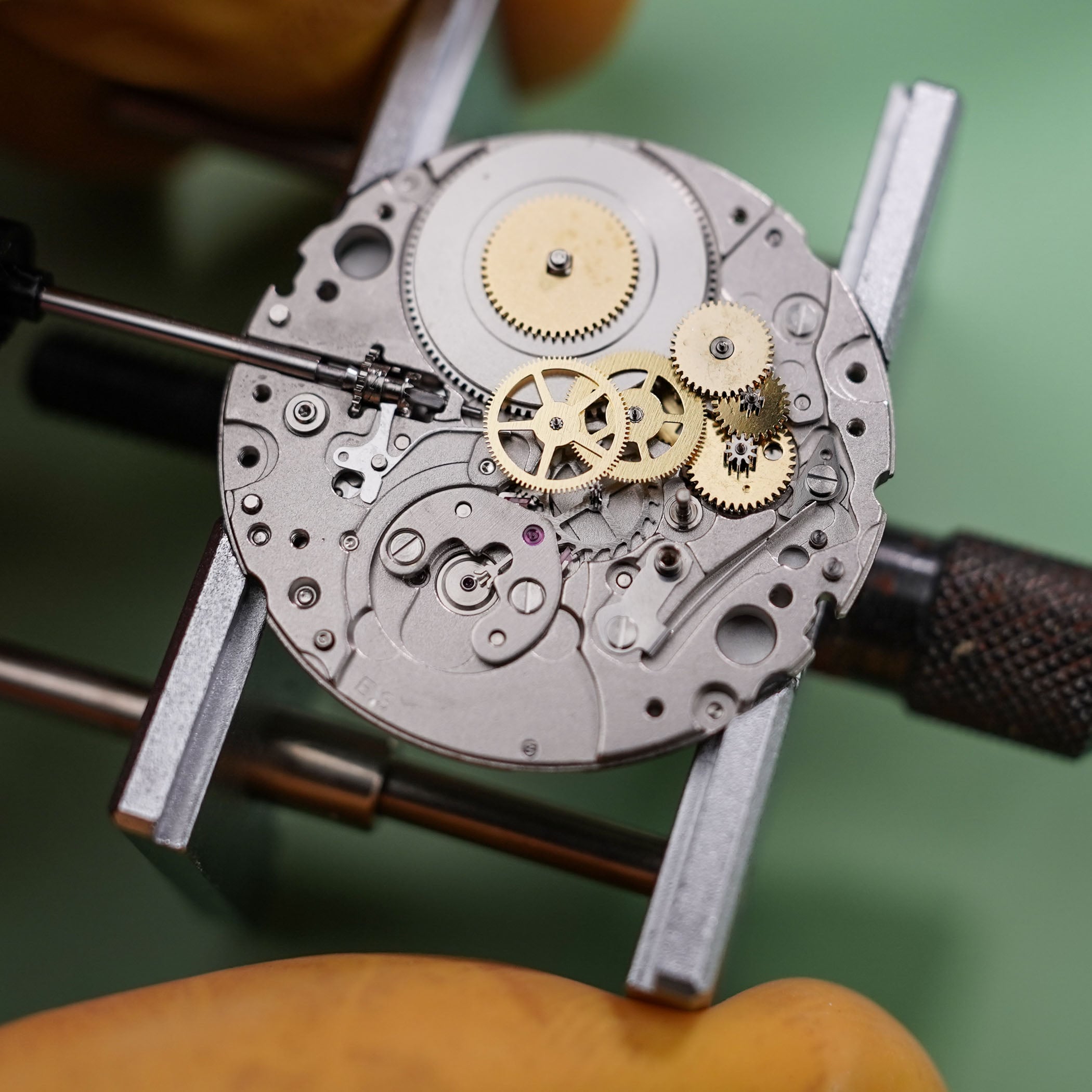

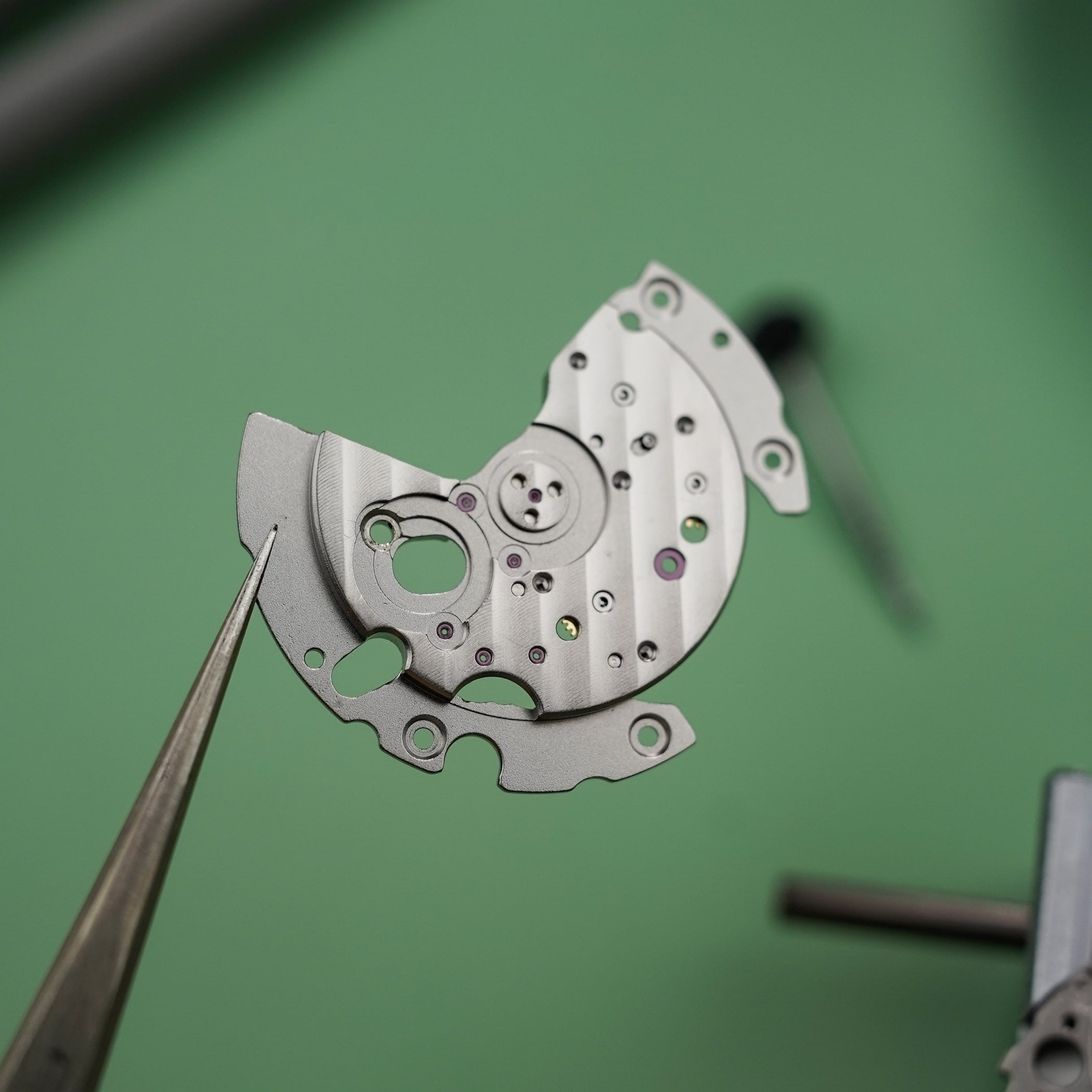

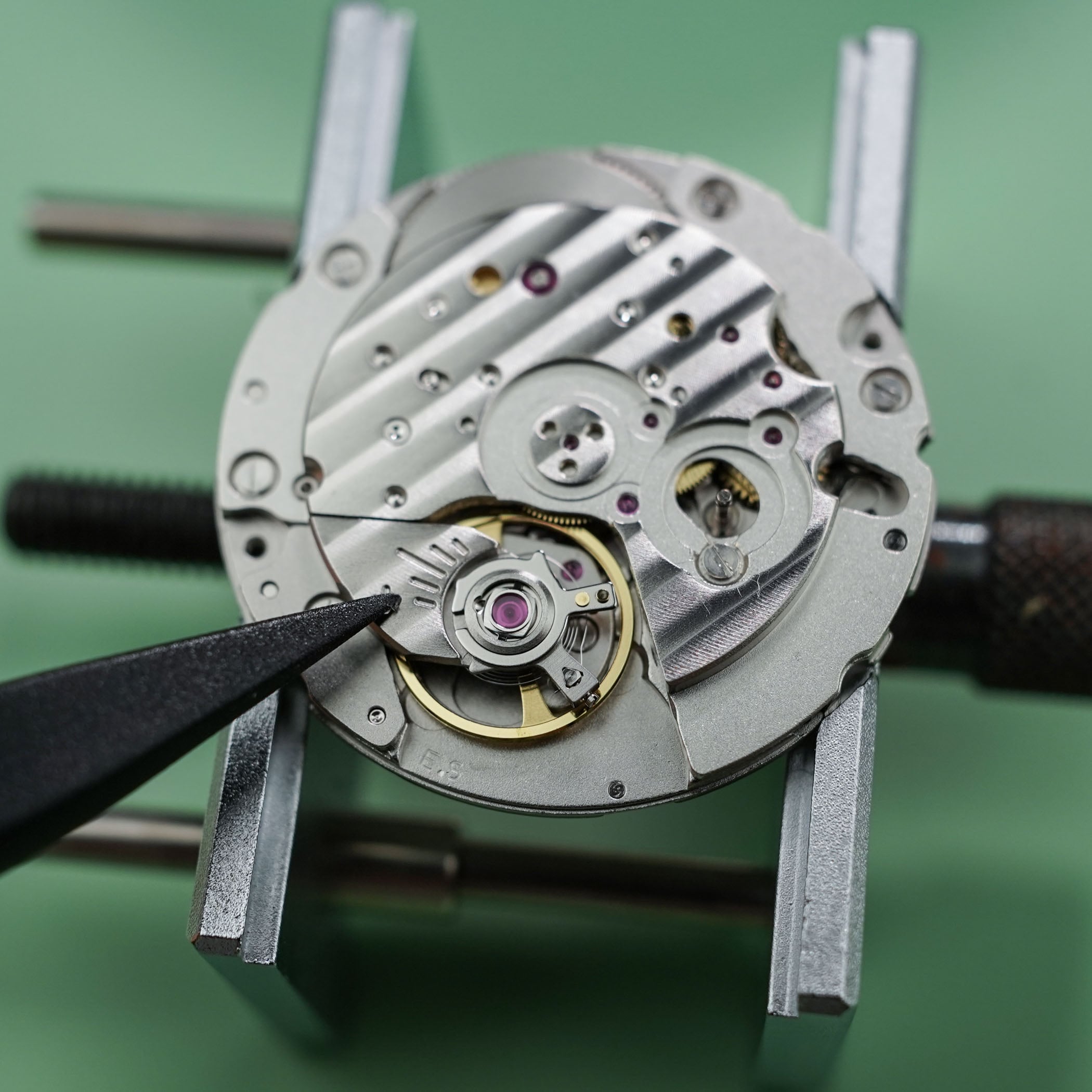

I move on and take off the top three-quarter plate, which holds a lot of components in place. As soon as I do that, almost the entire running gear from the barrel to the balance wheel is laid bare:

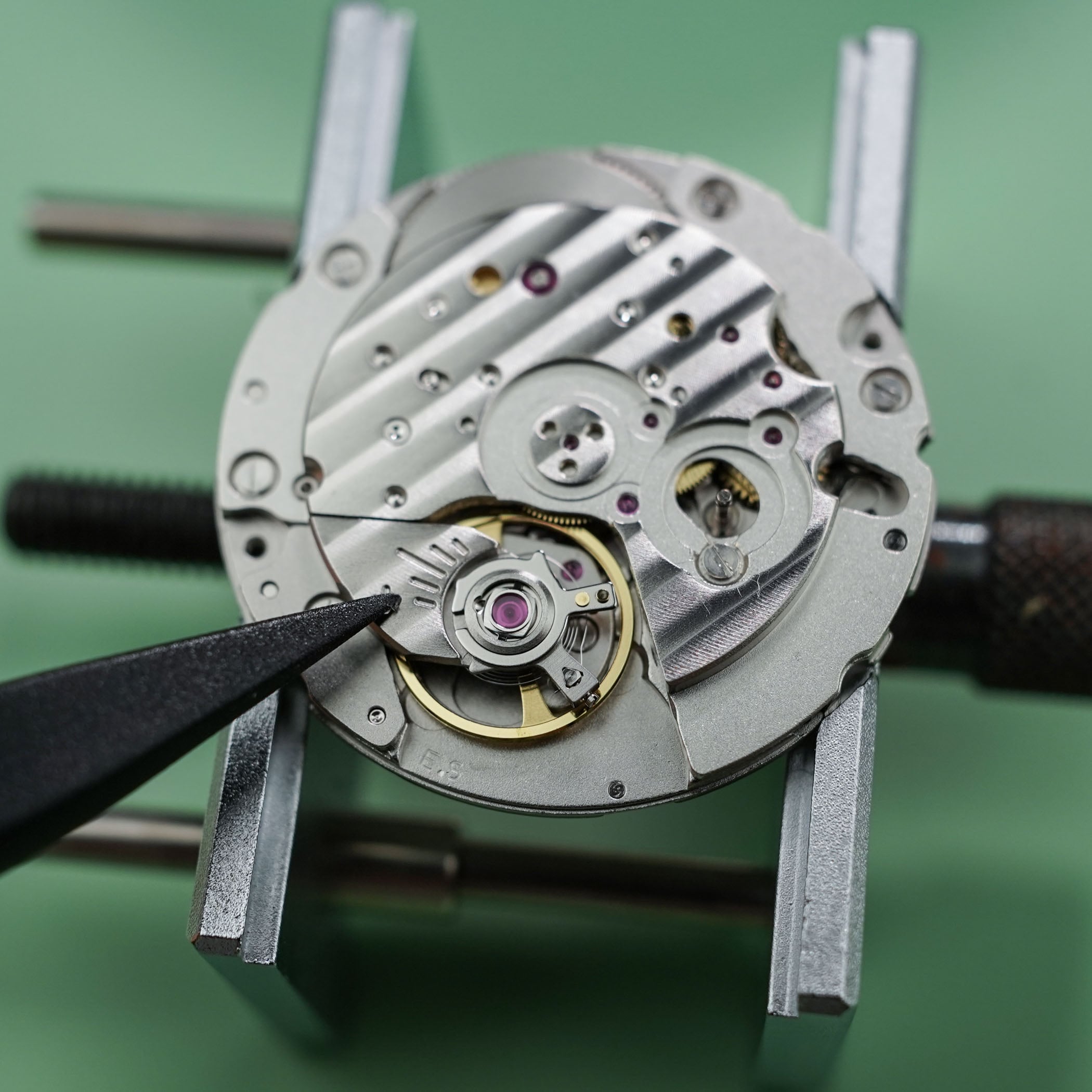

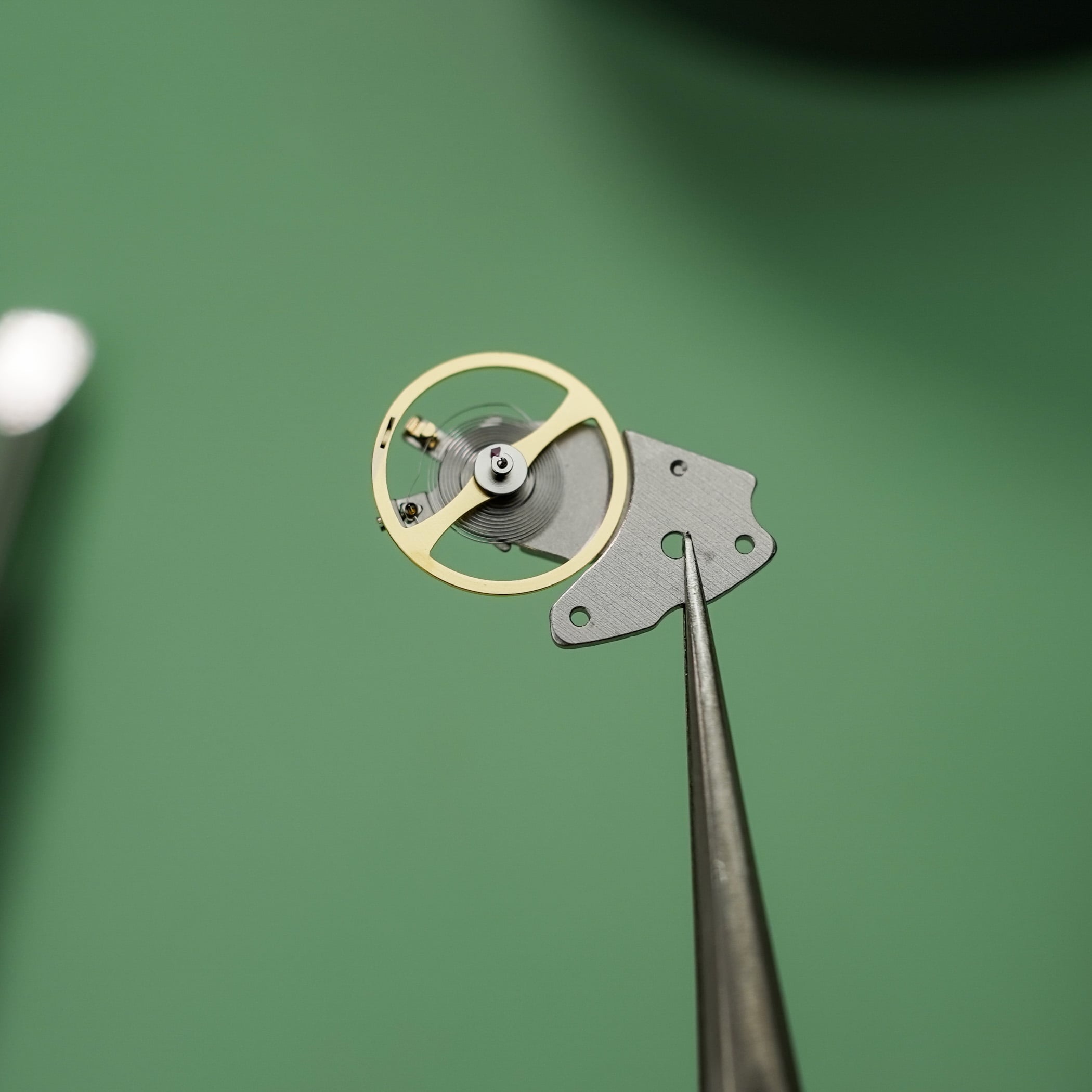

One by one, I remove the entire balance assembly, the intermediate wheels, the third and fourth wheel and so on. What’s evident is the Parashock shock-absorber over the balance staff, a development by Miyota, and how it can be regulated.

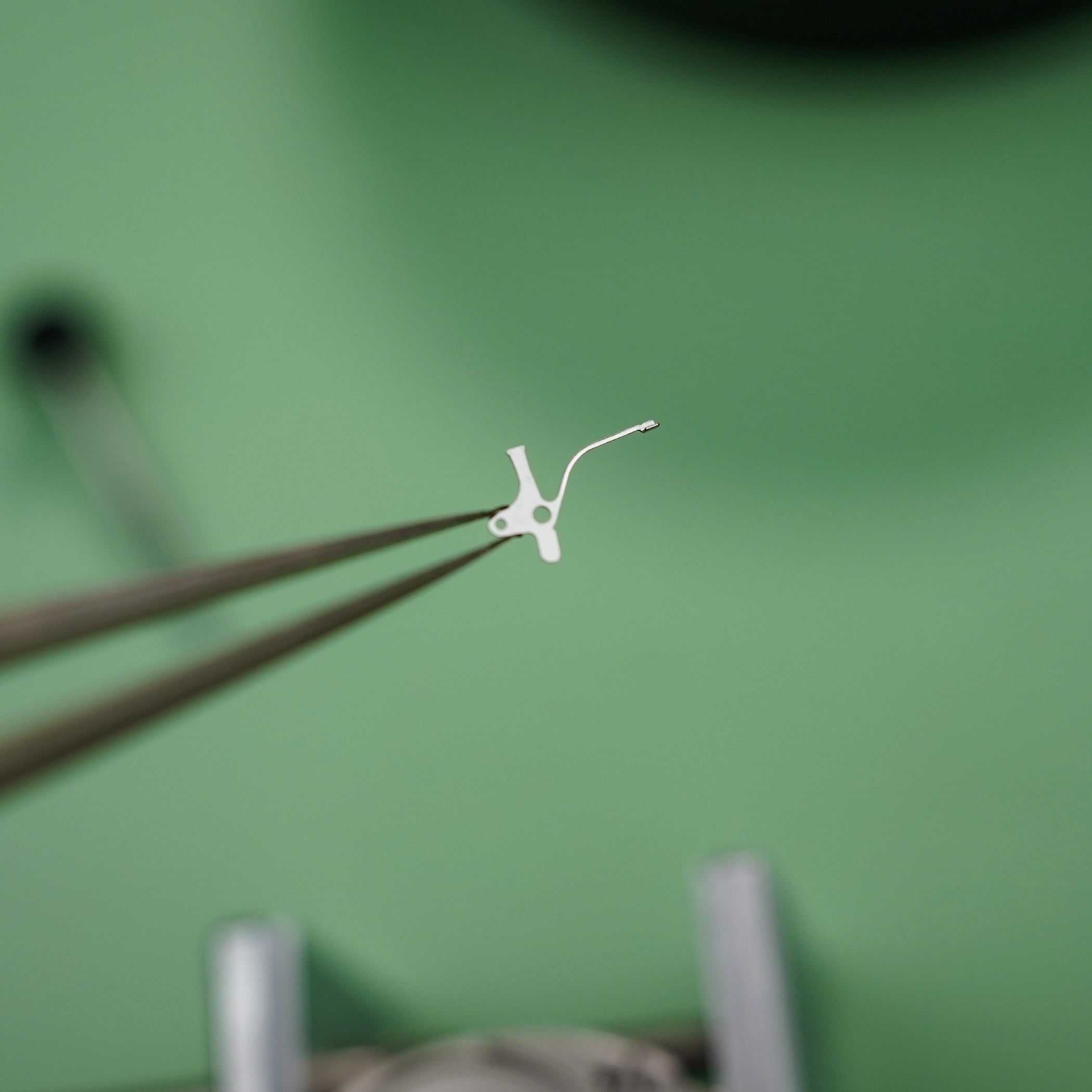

Where you would expect a fine-regulating system like a swan neck, or a poising screw with an A-shaped arm, there’s none of that here. Instead, there’s a plus-minus scale with adjustments made on the rim that also holds the hairspring studs. It’s a nifty solution that helps with manufacturing and assembly.

Moving on, you can also spot the brake lever for the seconds hand (the hacking-seconds mechanism).

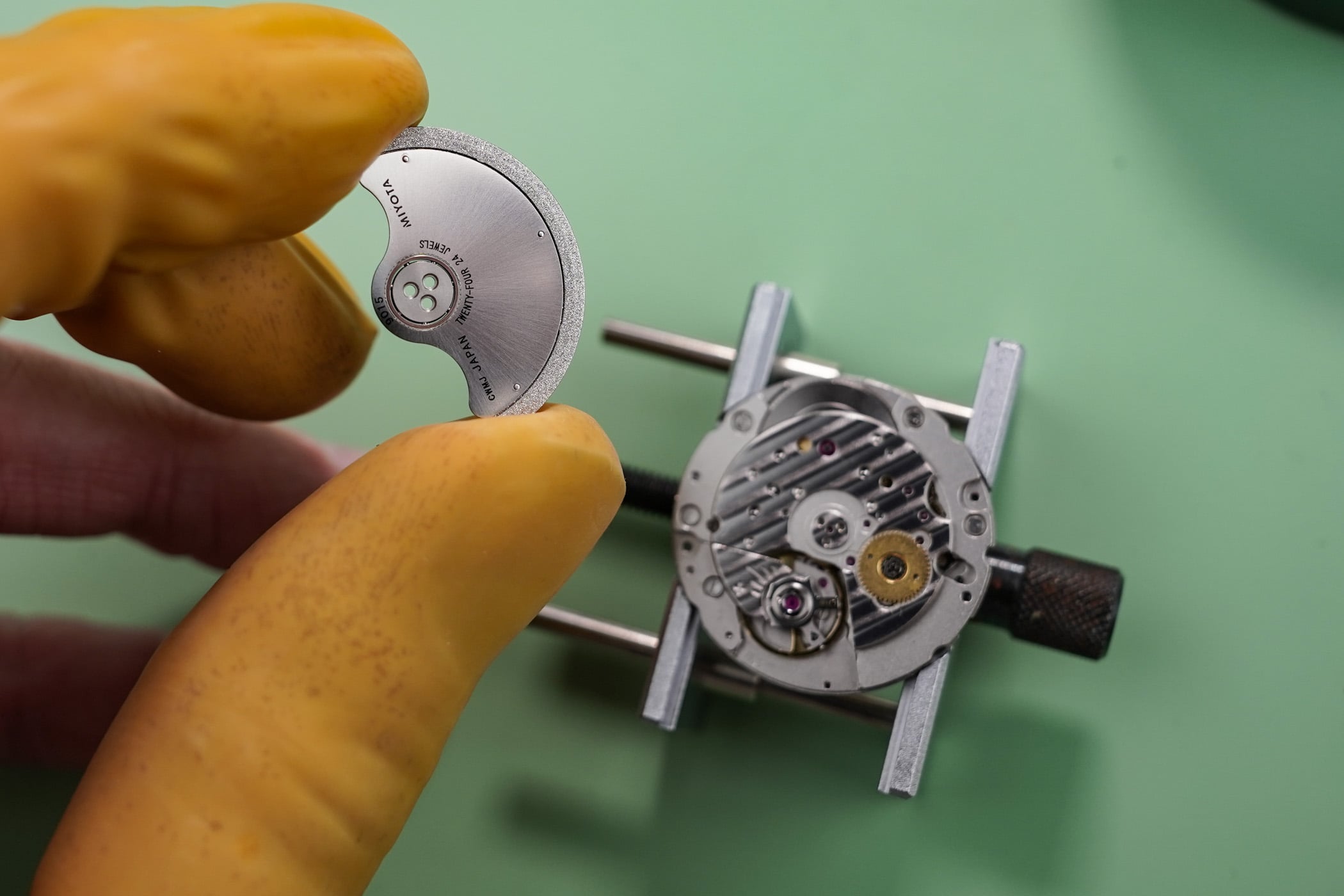

Now that I have all this removed, I can turn to the other side of the movement, as there’s more to be discovered there. I first need to take off the hour wheel guard, which frees the date disc and the date jumper. You can then also notice the setting wheel and lever that moves the date disc in one direction, but moves out of the way when you turn the crown in the other direction.

This is about how far I dared to go with my admittedly rather limited watchmaking experience and skills. Putting everything back together is a bit more challenging, especially the barrel-and-train-wheel bridge, which requires perfectly aligning a multitude of parts.

More detail than expected

My main takeaway from all of this was the level of finish in the movement. I am aware that the 9000-series is positioned as premium by Miyota, but it is still often perceived as unfinished, or at least as very basic. While that is true when compared to hand-finished movements, of course, the finishing was honestly rather surprising to me. There are some polished elements to be found, even in places where it’s not mandated by functionality. There are the bevelled edges on screw sinks, crisp ribbing on bridges and plates, the frosting on all sides of the rotor’s oscillating weight, perlage on the hour wheel cover (calibre 90S5), and so on.

Then there’s the scale at which Miyota’s movement production operates. Things are done on a huge industrial scale and cannot be compared to artisanal watchmaking in any way, yet they also involve manual labour. The terminal curve in the balance spring, for instance, is shaped by hand. But neither can ETA’s nor Sellita’s production methods. However, the level of precision that’s needed to produce movements reliably and cost-effectively, as well as the rate at which Miyota produces, is incredible. Considering Miyota even surpasses industry giants like Seiko is amazing to me, and puts things in a new perspective.

And then, finding true attention to detail and a surprising level of finishing only adds to my appreciation of Miyota and its 9000-series movements. Through it and other movement families, Miyota offers an impressive spectrum of functionality, backed by decades of expertise, resulting in reliability, serviceability, and repairability, at a very fair price. And all at a level the Swiss simply can’t match…

For more information, please visit miyotamovement.com.

3 responses

Excellent Article, Please deconstruct others ?

Loved it, we need more of that!

You are at your best when you present articles such as this; deconstructing and taking us inside the differences and similarities between competing movements, rather than having to read through a review of a watch brand’s “newest” offering, trying to justify another of their outrageous grabs for money.