Learning The Art Of Vitreous Enamel Dialmaking Thanks To anOrdain

There's a lot more to it than just putting powder on a dial and firing it in a kiln!

When we recently reached out to anOrdain to see if we could conduct an interview about this very interesting brand, they came back to us and said, “we can do you one better!”. Curious as we are, we wanted to know more. In an effort to show, rather than tell, they wanted to open their atelier doors for us and come find out more for ourselves. We jumped at the opportunity, and we flew one member of the MONOCHROME editorial team to Glasgow, Scotland, to discover the traditional art of vitreous enamel dials, a signature element in all anOrdain watches up to this point. And as it turns out, it’s not easy to get right!

In essence, the art of enamel dials dates back to the early days of watchmaking and has always been an important element in the craftsmanship of clocks and watches. Even now, very early high-quality enamel dials can still look amazing! There’s a soft, luscious shine to an enamel dial that is virtually impossible to recreate with any other technique, and it can’t really be done by a machine. It takes great skill to finish an enamel dial to perfection, as it is an extremely delicate process. So with our visit to anOrdain in Glasgow, we had the perfect opportunity to learn more!

Before diving into the art of enamelling, it’s important to make one clear distinction first. Some people mistake cold enamelling as a form of enamelling, while technically, it isn’t. The process that people often refer to as cold enamelling sees a resin-type substance dispersed on a dial blank. Cold enamel generally cures and hardens at room temperature. An example of a watch with a ‘cold enamel’ dial is the Holthinrichs Ornament 1 with ‘Delft Blue’ porcelain dials. This process results in a rich, glossy finish and can be done in a vast range of colours.

In reality, the only genuine enamelling process where a powdered substance is deposited on a base material is hot enamelling. This is also known as Grand Feu enamel or vitreous enamel, which is what’s done at anOrdain. Subgenres of vitreous enamel are techniques like champlevé, cloisonné or flinqué, but that’s for another time perhaps.

Molten glass powder

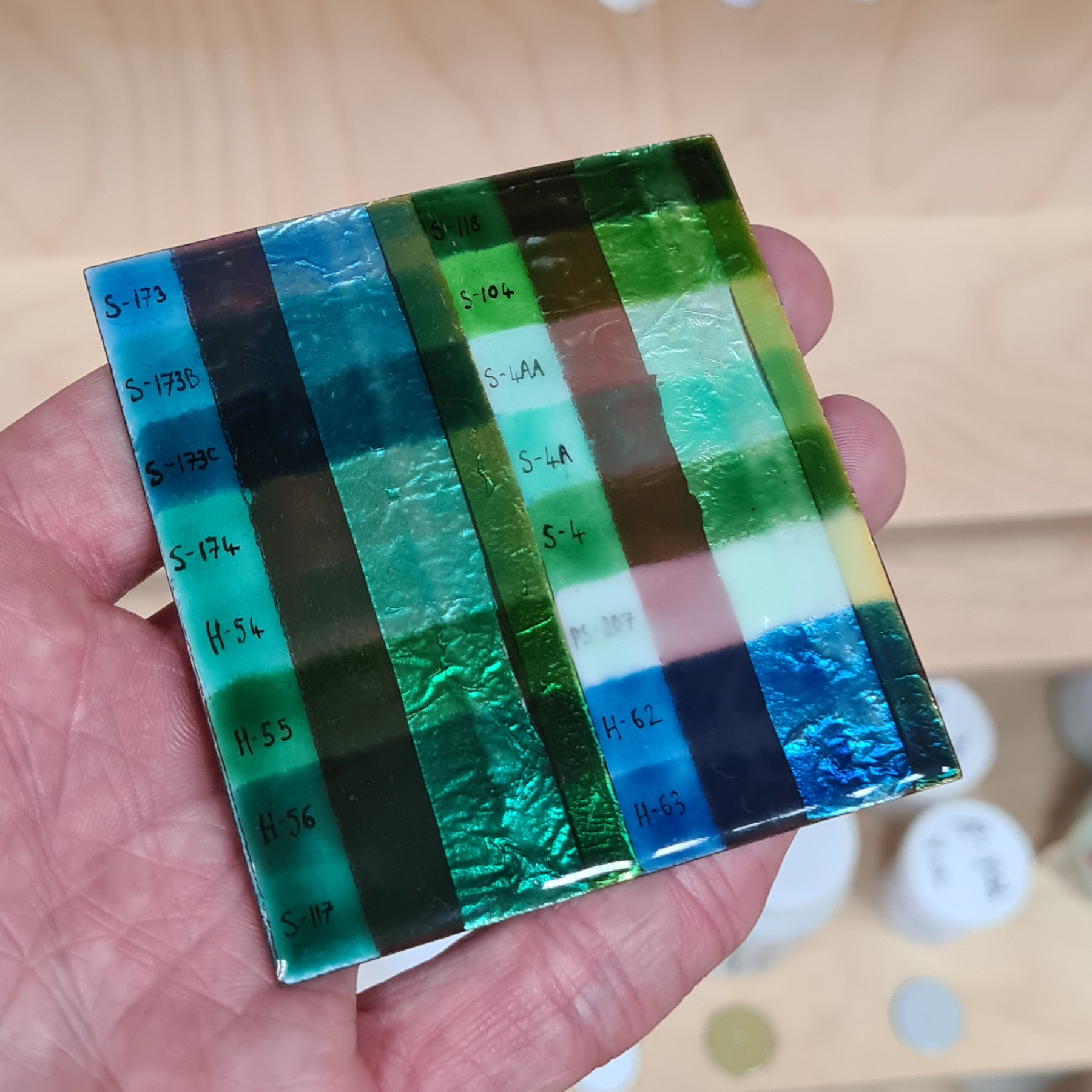

Every type of enamel starts as soft glass powder derived from silica mixed with various other compounds. This is melted down in a crucible until it’s a transparent crystal-like liquid. Various other substances can be added to create unique and uniform colours. Cobalt creates blue tones; iodine is used for shades of red, and so on. Making a batch of enamel takes an average of 14 hours in a kiln to properly bond together before it’s taken out to cool. The next step is to break down the solid piece of enamel into smaller chunks before grinding it into a powder again.

anOrdain sources its enamel from a number of suppliers from the UK and mainland Europe. Several things are critical when a dial artist starts making an actual dial. First, the blank dial. This needs to be in perfect condition, as blemishes, burrs and warps can result in imperfect enamel dials or even cause breakage during the firing steps. Second, the powder. It’s essential that the enamel powder is ground to a specific consistency. To achieve this, a dial artist uses a pestle and mortar to grind down the powder. During the grinding process, it’s mixed with water to rinse out any unwanted elements and obtain a uniform powder. The craftsman or -woman uses the sound and feel of the pestle against the mortar to determine if it’s ground down enough. It’s then put in a small cup and mixed with demineralised water to make a smooth paste.

a delicate process

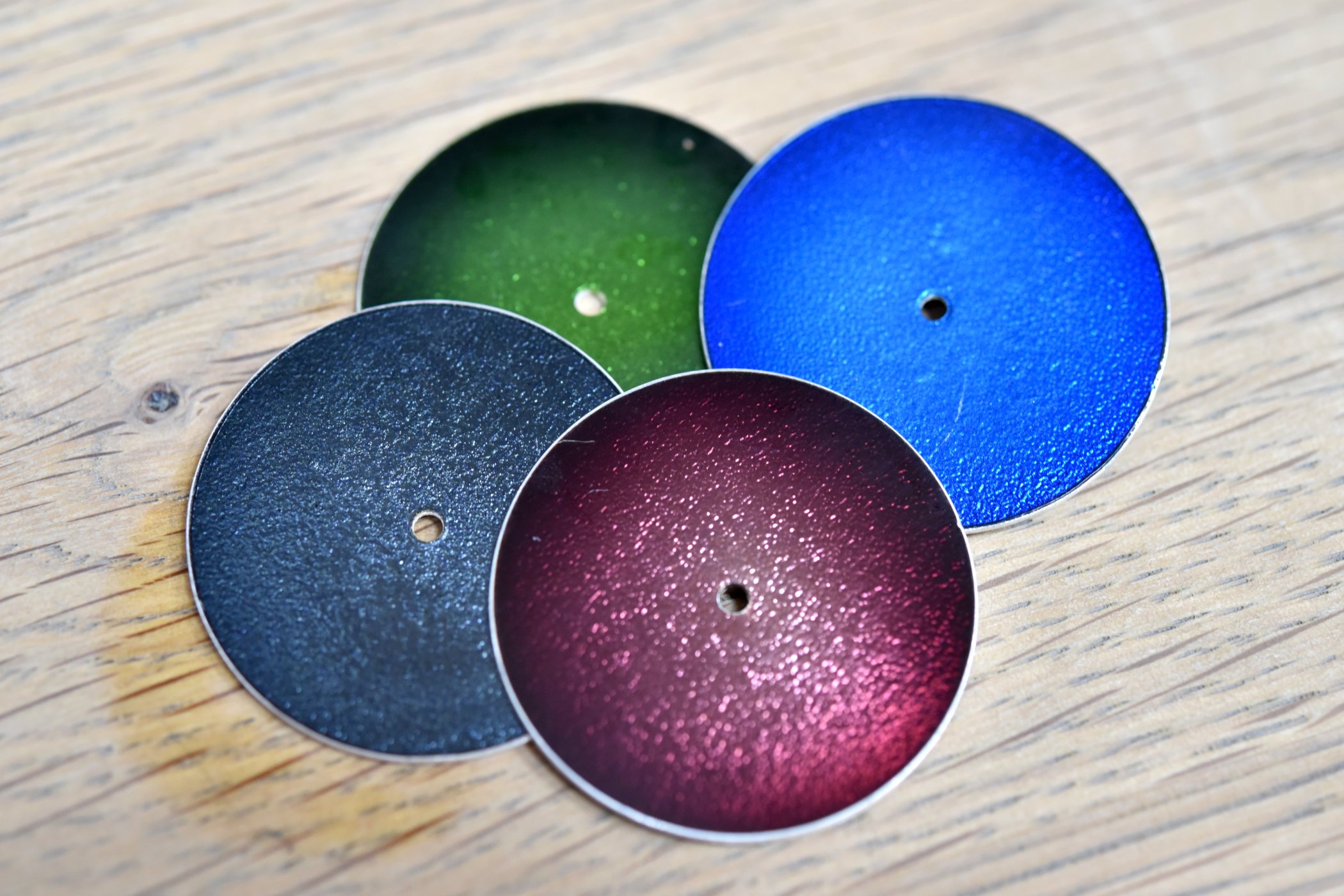

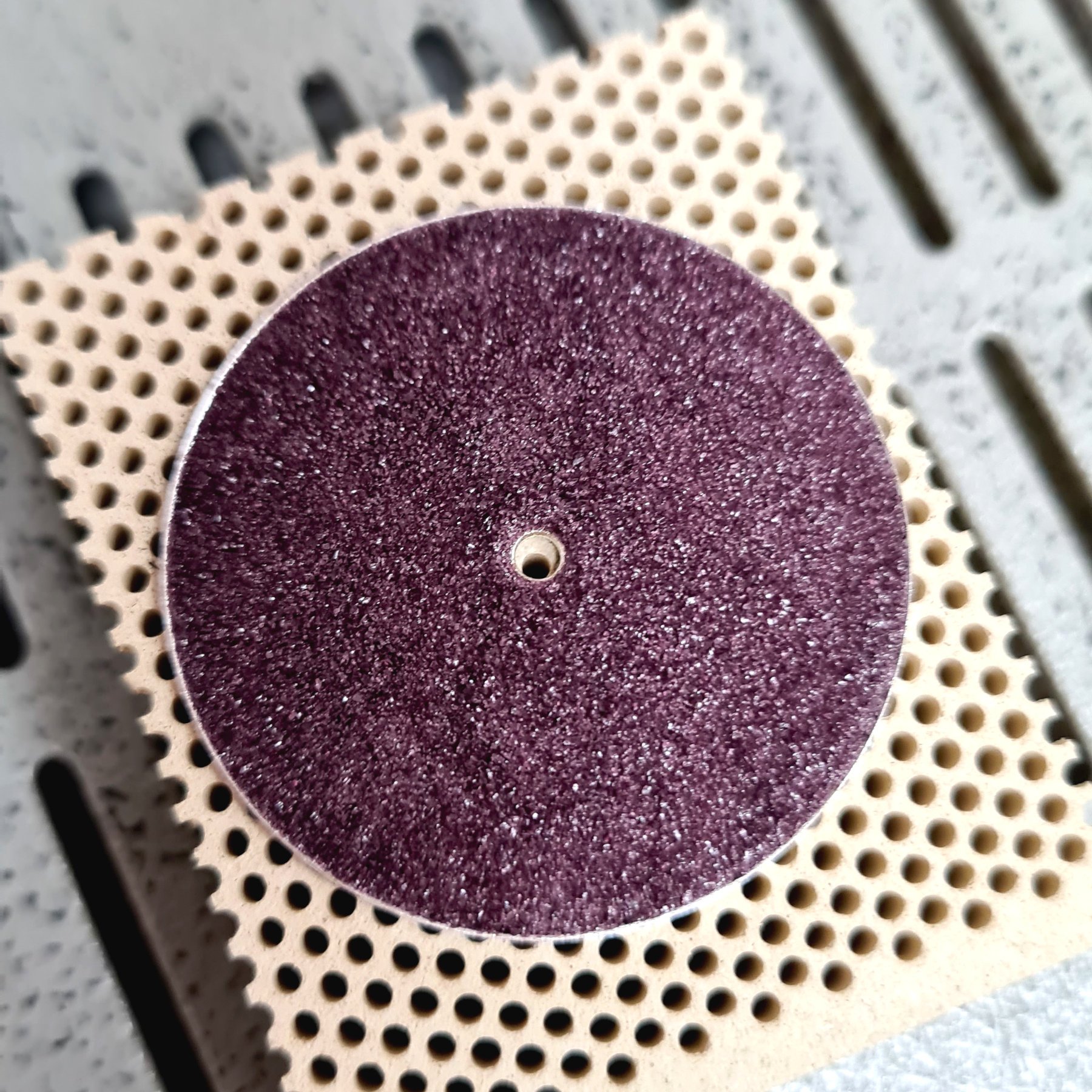

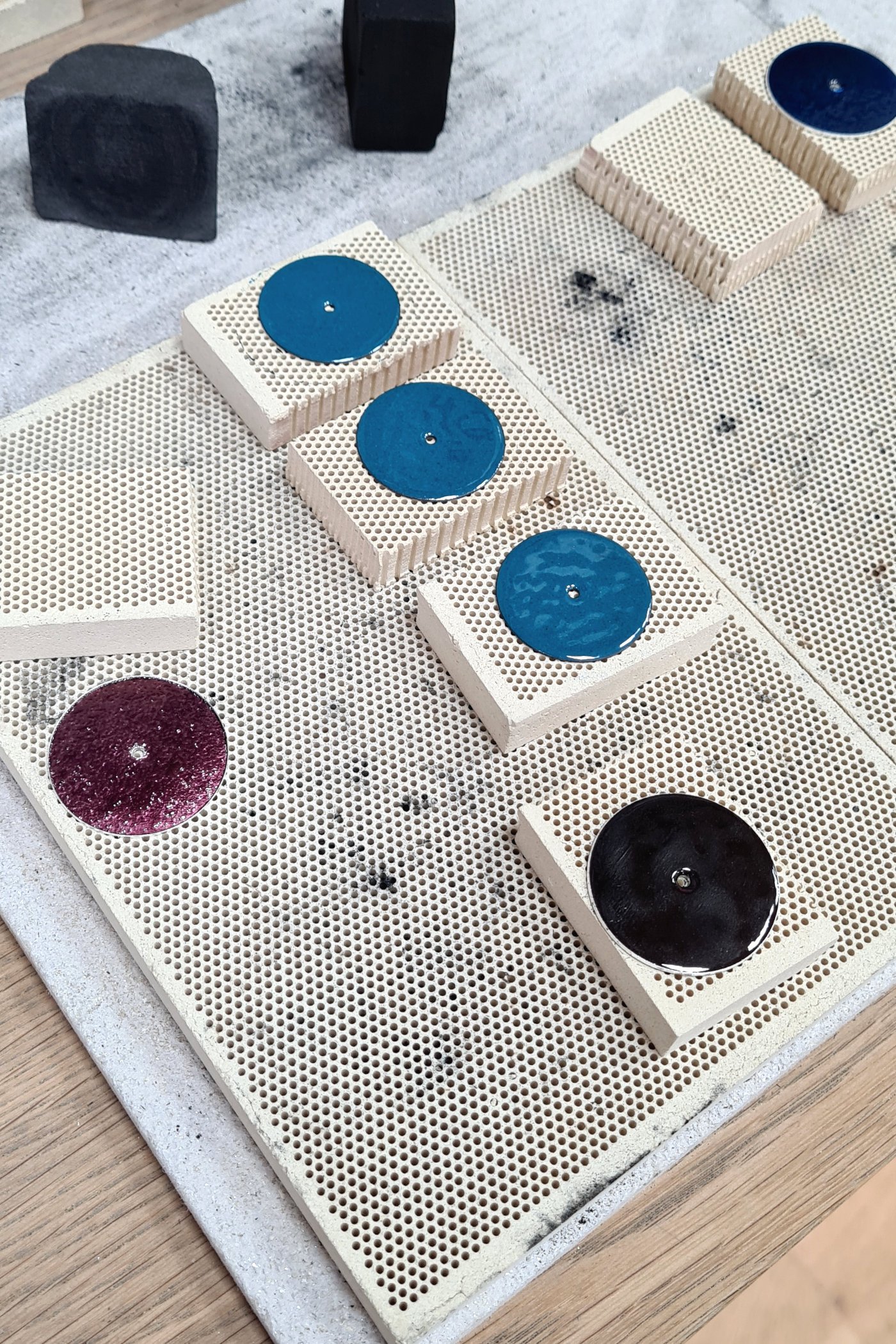

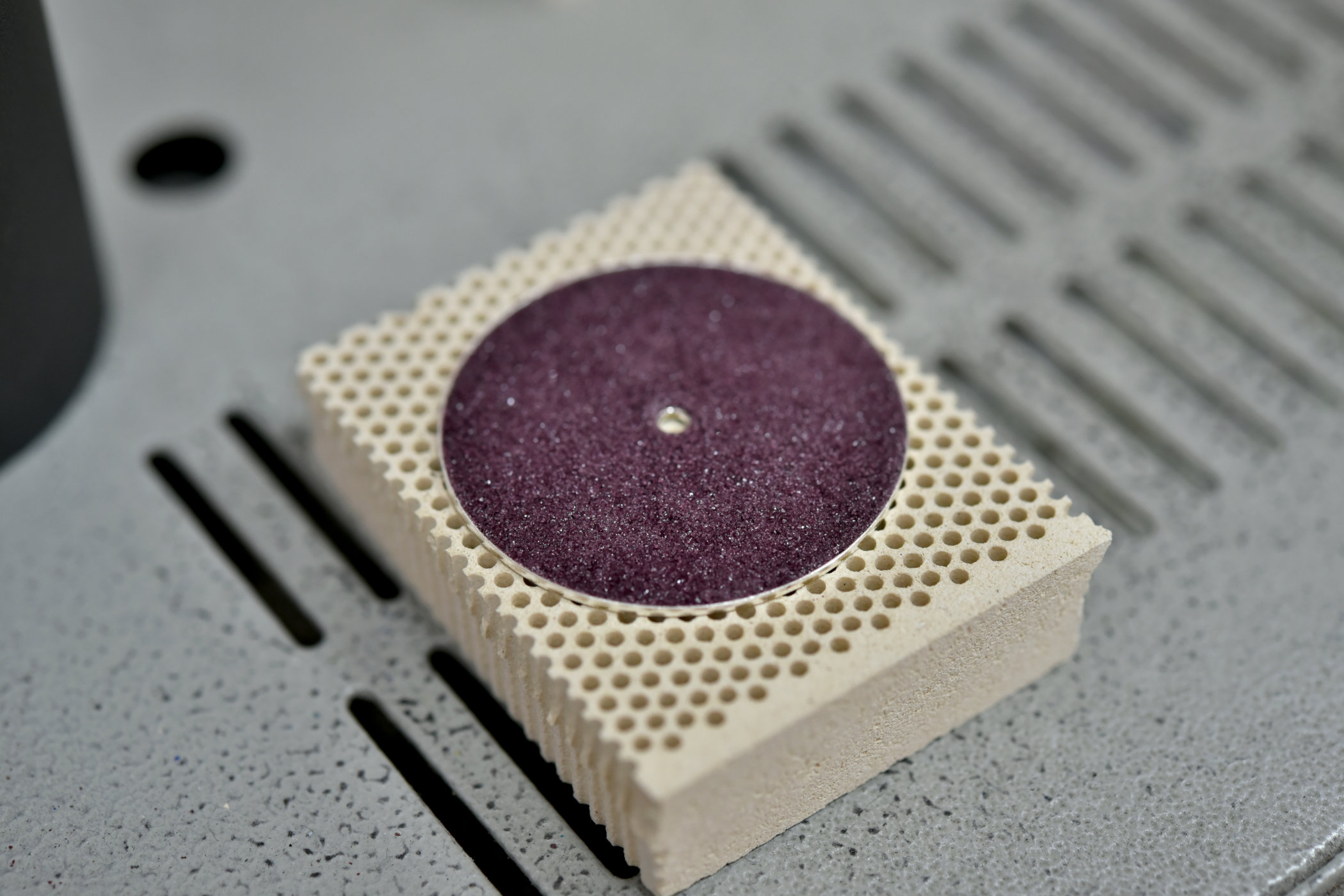

Once the powder is prepared, the dial artist can begin applying it to the blank. This is done by carefully transferring it onto the dial with a brush in an even layer for transparent enamel, but it can also be done using a sieve for opaque dials. After the first layer is done, it’s fired in a kiln that can be anywhere between 800 and 1200 degrees centigrade. The precise temperature, and length of firing the actual dial, varies per colour. After a dial is fired, it needs some time to cool down before the next layer can be applied. Slight imperfections or particles trapped inside the previous layer can be carefully ground out between the first three to four layers. However, this is no longer possible for subsequent layers, as the ground-out spots would show up in the final dial.

A dial artist works on four to six dials of the same type in rotation at any given time. Depending on the type and colour of the enamel dial (opaque or translucent), each dial is built up with six or seven different layers. Once the final layer is done and approved after inspection, it’s put into a specialised machine to sand down and polish the top surface. At any given time during this entire process, a dial can get damaged or broken. Through trial and error and understanding every single aspect of the production of enamel dials, anOrdain has managed to reduce the rejection rate to roughly 30%. This still sounds like a lot, but the fact of the matter is that most others don’t even come close.

From start to finish, the slightest changes or mishaps in the making of a dial can render it useless. It was through one of those mishaps, though, that the Scottish team discovered how to make translucent fumé dials. A type of dial we mostly associate with one or two other high-end watchmakers, but it was anOrdain that first introduced it in 2019!

Happy little accidents

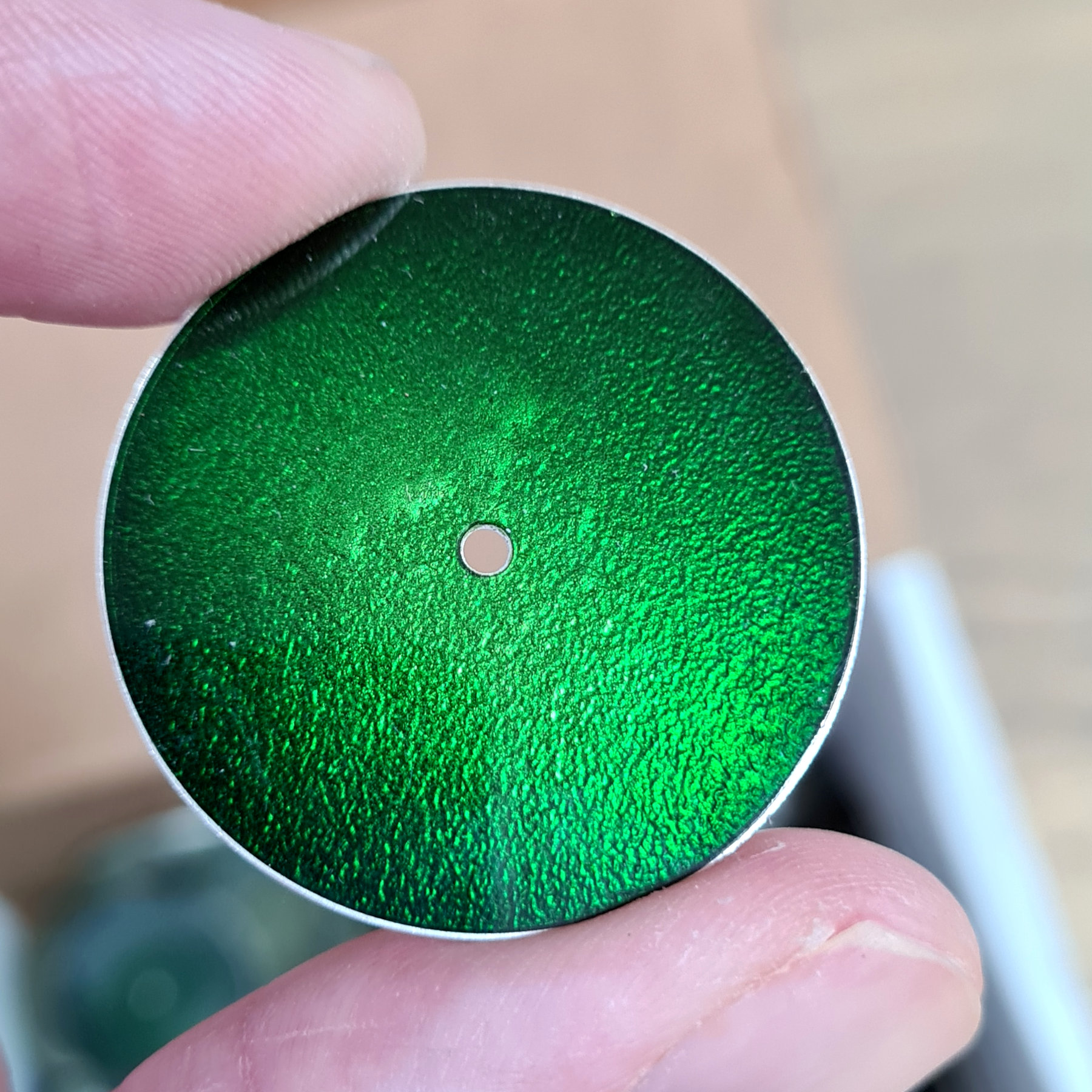

At first, anOrdain used copper dial blanks for most of its opaque (and some transparent) enamel dials. This proved a stable enough material but didn’t do the vivid nature of translucent enamel dials any good, as the colours ended up being too dark. The experiment to switch from copper to silver dial blanks eventually led to the discovery of how to make fumé enamel dials. The silver blanks were softer and subsequently warped under the stress of the firing. At one point, a dial warped slightly upwards in the middle, creating a shallower level for the enamel around the centre and a deeper level towards the outer edge.

The effect was profound, and the colour was bright in the centre but darkened towards the outer perimeter. Unable to repeat the process to a satisfying degree, a chance encounter with a traditional toolmaker in Birmingham provided the solution! This toolmaker was able to factor in the needed warpage and essentially created a domed dial in silver to achieve the desired effect! The margins here are extremely slim, of course, as a dial blank is only 1mm thick. It goes to show the complexity of producing something of this nature. Something the craftsmen and -women at anOrdain have mastered through experimentation but also understanding what’s needed from start to finish. Regardless, there’s always the potential loss of a dial!

So, next time you get your hands on any watch with a vitreous enamel dial, and possibly/preferably an anOrdain, of course, you can appreciate it a little bit more, knowing the care and attention put into each one!

For more information, please visit anOrdain.com.

2 responses

These dials are wonderful, but I feel, from pictures, they are let down by the case.

Now that I’ve read your article I can enjoy my anOrdain more than usual. The best watch company I have ever dealt with.