A Comprehensive Overview of Patek Philippe’s Annual Calendar, and How the Complication Came to Life

A look into the fascinating history of Patek Philippe’s recent complication, and its genius mechanics at work.

Calendar indications are a classic of watchmaking. But not all calendar watches are born equal. As our own Xavier Markl explained in this Technical Perspective article, calendar watches range from basic date displays to the ultra-rare and highly complex secular calendar mechanism and everything in between. Next to the highly praised perpetual calendar, there is a complication that has gathered great interest in recent years following its invention in 1996, the annual calendar. An almost-perfect mix of complexity, practicality and reliability, its creation has to be credited to Patek Philippe. Today, in our latest in-depth historical and technical article, we’re taking a closer look at what makes it such a great complication, how it came to exist and what are the most notable Patek Philippe Annual Calendar watches.

Calendars and clocks

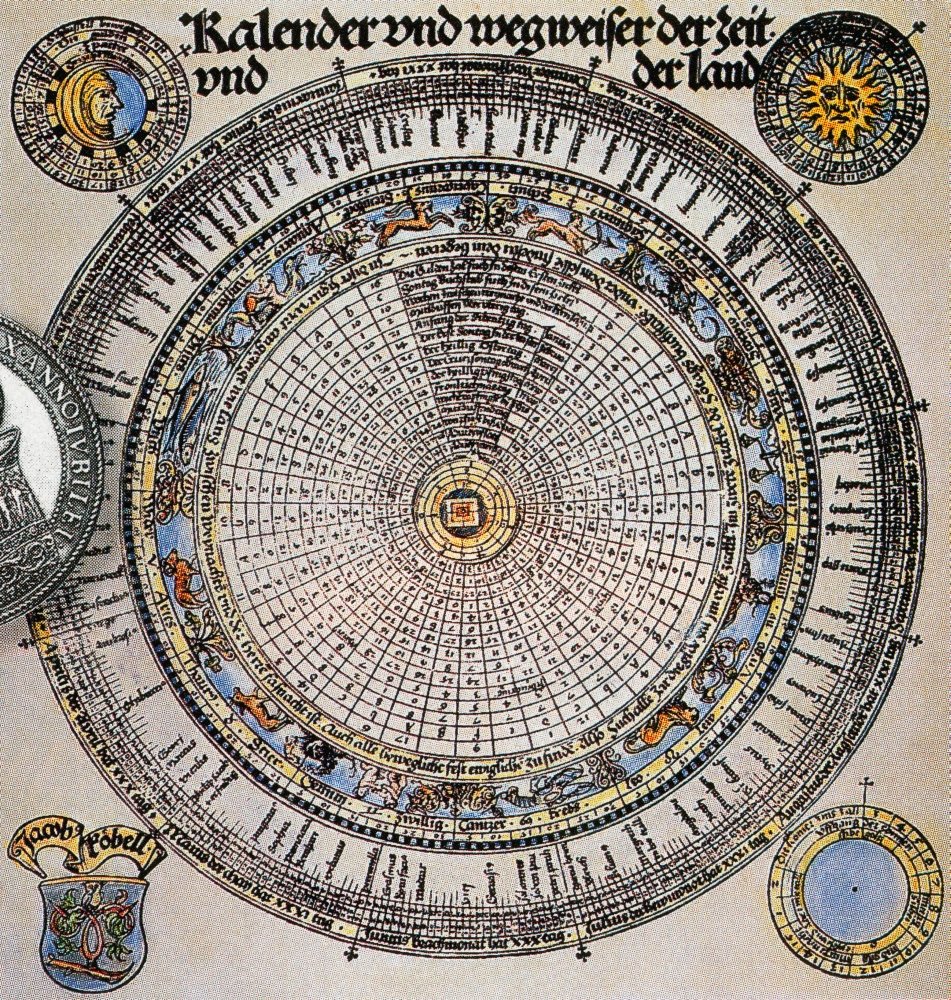

When monks in 14th-century medieval Europe first invented clocks, they were primarily designed as mechanical calendars to track the seasons, religious holidays, and rituals. Even as timekeeping by the hour became more widespread, calendars remained integral to clock design. Examples are well known across Europe; one is the clock commissioned by King Henry VIII for Hampton Court Palace around 1540, which not only displayed the hour but also the day of the month, the month, the position of the Sun, the moon phases, and other astronomical details.

Complicated spring-driven clocks were already in use by the 16th century, which is when the Gregorian calendar, now used in most parts of the world and internationally accepted, was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 to correct issues in the earlier Julian calendar (in use since 45 BC). One key problem with the Julian system was its inaccuracy in calculating the date of Easter, which caused it to drift over time. The Julian calendar, with 365 days divided into 24-hour days, seven-day weeks, and months of 30 or 31 days (except February, with 28 days), did not perfectly match the time it takes Earth to orbit the Sun – approximately 365 days, 5 hours, 49 minutes, and 16 seconds.

Pope Gregory XIII introduced the leap day to correct this discrepancy, adding February 29 every four years. However, even this adjustment slightly overcompensates for the difference, so the Gregorian calendar omits leap years in centuries not divisible by 400. So 1700, 1800, 1900 and 2100 are not leap years, but 1600, 2000, and 2400 are leap years.

A great example of 16th-century timekeeping is the Buschman Renaissance clock, housed in the National Maritime Museum in the UK. This table clock, dating to around 1586 and believed to have been made by Johann Reinhold of Augsburg, features intricate gearing that provides over forty indications, including calendar data and telling the time. The clock is detailed in an excellent article by Víctor Pérez Álvarez in “Antiquarian Horology” (Volume 39, No. 3, September 2018). It’s a fascinating read for anyone interested in the subject, though it doesn’t directly relate to the concept of a perpetual calendar – a mechanism that automatically tracks the date and month while considering leap years without needing adjustment until the year 2100, as long as the watch remains running and accurate.

In contrast, the annual calendar complication – our hero of the day – typically tracks the month, weekday and date automatically from month to month. Yet, once a year, on March 1, the user must make a single adjustment to compensate for the short February.

From Thomas Mudge’s perpetual to Patek Philippe’s annual, via Patek Philippe’s perpetual

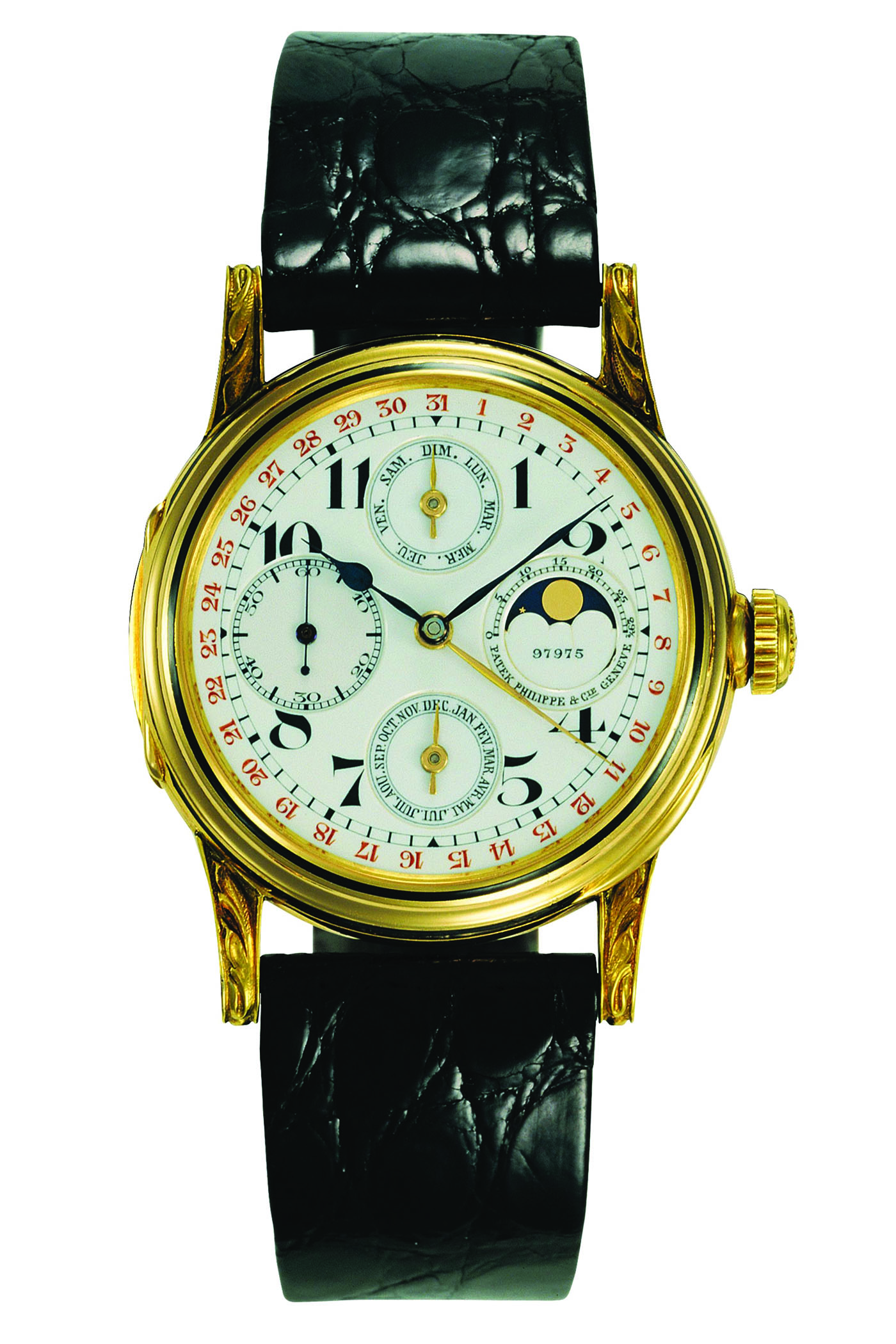

Returning to the topic of calendars in watches – and skipping a good part of watchmaking history – it was the English watchmaker Thomas Mudge who, in 1762, first introduced a perpetual calendar complication inside a 50mm pocket watch. The complexity and precision required for such a mechanism must have deterred other watchmakers from pursuing it (Breguet’s “Marie Antoinette” is one exceptional exception) as it wasn’t until nearly a century later, in 1864, that Patek Philippe produced another perpetual calendar pocket watch. In 1898, Patek created a perpetual calendar for a ladies’ pendant watch, which remained unsold. The movement was later re-cased in a 34.4mm wristwatch in 1925 and sold in 1927 to American collector Thomas Emery.

Emery’s piece was unique. Patek Philippe began serial production of perpetual calendar wristwatches with the reference 1526 in 1941, and in 1962, the brand introduced its first automatic perpetual calendar, the reference 3448. So why all this talk about perpetual calendars when the focus is on annual calendars? It’s just that until the 1990s, the idea of a watch calendar mechanism that required only one yearly adjustment – an annual calendar – was completely overlooked by watchmakers. That is until Patek Philippe introduced it. The patent granted (CH685585G) described the innovation as an annual calendar mechanism designed to address the drawbacks of fully mechanical perpetual calendars. Those drawbacks? Perpetual calendars are notoriously complex and costly and traditionally use a hand for date indication.

To understand why Patek sought to introduce a simpler and more affordable calendar watch, one must consider the state of the watchmaking industry in 1996. Insights from an interview with Philippe Stern, as reported by seasoned journalist and our dear friend Pascal Brandt (published in “Journal de Genève” in 1996), shed light on the motivations behind this move.

The Context

The 1990s marked a period of renaissance for the Swiss watch industry after the challenging years of the 1970s and 1980s. Reflecting on 1996, Philippe Stern, then head of Patek Philippe, referred to it as a period of stabilisation, having “lived through the exceptional situation between 1988 and 1993”. However, the industry’s first four months of 1996 showed continued regression, with exports down compared to the same period in 1995. While steel watches experienced considerable growth, gold, gold-plated, and bi-metal watches saw regular declines, and overall exports to major markets dropped.

The rising success of mechanical watches as luxury products led many brands to abandon their niches and move upmarket, offering complicated watches in quantities that diluted the concept of exclusivity – an important and proven marketing tool for luxury. As Stern pointedly remarked, “in five or six years, more minute repeaters were produced than had been made in two centuries”. To preserve the brand’s integrity, a few years earlier, he had limited Patek’s production of complicated watches, even at the cost of turnover.

At the same time, Stern recognised a significant price gap between time-only and highly complicated watches, with Patek Philippe operating primarily in the CHF 10,000 to CHF 40,000 segments. He saw the need for the development of “serviceable complications” – innovative watches that were more accessible than high complications like perpetual calendars and minute repeaters – thus providing its clientele with a smoother entry into the world of complications and, equally important, offering practical value to the wearer. The first of these was the world’s first annual calendar wristwatch, the Patek Philippe Ref. 5035, revealed at Baselworld in 1996, which created a new category of complications now offered by many brands (A. Lange & Söhne, F.P. Journe, Laurent Ferrier, ochs und junior, Omega, Parmigiani Fleurier, IWC, Longines, Glashütte Original and Rolex, to name a few).

1996 – The Annual Calendar Ref. 5035

The 1996 Patek Philippe Ref. 5035 featured a 37mm yellow gold case, 11mm thick, with a crown in the traditional position and three corrector pushers on the sides for adjusting the corresponding displays. The dial had a clean and quite interesting layout, with two sub-dials positioned above the central line – month at 3 o’clock and day at 9 o’clock – and a 24-hour sub-dial placed just above the date window at 6 o’clock. The Roman numerals, including the traditional “IV” instead of “IIII”, and the gold hour and minute hands were coated with luminous material for visibility, while the central running seconds hand circumnavigating the peripheral railroad-style minutes track distinguished the appearance of an annual calendar from the QP.

The watch offered a water resistance of 25 meters, and the caseback featured a sapphire crystal, allowing a view of the beautifully decorated and finished movement, the calibre 315 S QA (Quantième Annuel), which incorporated the annual calendar mechanism module as described in the patent CH685585G which listed Cedric Fague and Philip Barat as inventors.

The Calibre 315 S QA

Calibre 315 S QA is a module with an ingenious new mechanical way for the calendar to function, added to calibre 315 S, then Patek’s primary central rotor automatic watch movement with a 21,600 vibrations/hour frequency, which replaced the problematic calibres 310 and 335 and was produced from 1984 to 2005, until the arrival of calibre 324. Notably, following a long-lived tradition at Patek Philippe to collaborate with schools and universities, the task to create an annual calendar mechanism that would have all the functions ensured by rotating parts, without levers, racks and other components actuated by winders or springs, was entrusted in 1991 to the final year students of the Geneva School of Engineering, and one of the young graduates named Cedric who worked on this Patek-initiated project landed the coveted job with the company – and still works there as a movement engineer.

The QA mechanism abandoned the perpetual calendar’s complex series of jumper springs, cams, racks, and levers and was based on a rotary stack of gear wheels with pinions mounted on a calendar plate and positioned between the base movement and the dial.

In months with 31 days, the calendar mechanism functions as follows: the date finger attached to the 24-hour driving wheel, which completes one full rotation every 24 hours, advances the 31-tooth date wheel by one notch daily. Through a gear train, this 31-tooth date wheel drives the calendar’s daisy wheel, which in turn moves the date ring, displaying the current date.

Beneath the date wheel, a 12-pointed month star wheel is hidden. The date wheel also drives this star wheel and completes one full rotation each year. The pinion on the star wheel carries the month display hand on the dial, ensuring the hand jumps accurately from one month to the next.

The automatic switching for short months – April, June, September, and November – requires the date wheel to advance twice, moving from the 30th to the 31st and then directly to the 1st. This task is managed by a calendar programme wheel, which is co-axial with both the 31-tooth date wheel and the month star wheel. The programme wheel features five rounded teeth corresponding to the short months, including February (which advances to the 29th in leap years to display the correct date). Naturally, the programme wheel completes one full rotation each year.

At the end of a 30-day month, one of the teeth on the calendar programme wheel engages the short-month rocker cam, causing it to rotate slightly counterclockwise. This positions its outer tooth in the path of the extra advance cam. As the 24-hour wheel continues its rotation, the tooth on the extra advance cam engages with the secondary date finger attached to the date wheel, advancing the 31-tooth date wheel by an additional notch to account for the transition from the 30th to the 1st. This operation begins just before midnight and takes about four hours to fully complete.

In simple terms, the date finger on the 24-hour wheel moves the 31-tooth date wheel forward by one notch each day. At the end of a 30-day month, a second finger steps in, advancing the wheel by an extra notch, allowing the date to skip from the 30th, past the 31st, to the 1st.

Interestingly, the patent claims that, “in a variant of the mechanism, it could be made perpetual by using the same principle of actuation of the superimposed fingers and teeth to control the passage from February 28 to March 1”. Was it ever done? Stay tuned. We will answer this question when we return with a review of Patek’s notable QPs.

And just like that, the PP Annual Calendar 5035 became a hot item, sought after by watch enthusiasts wanting to own a complicated Patek watch at a price that was not forbidding (about CHF 18300; in comparison, the 3940, a QP in yellow gold was offered at CHF 44,700 in 1997), as I am sure collectors who loved the idea of a “useful complication” and the watch’s elegant aesthetic also added the new QA to their wrists.

Annual Calendar Ref. 5036 with moon phase display (1998), Gondolo Calendario Ref. 5135R (2004), Ladies’ Annual Calendar Ref. 4936 (2005), new Annual Calendar Ref. 5146 (2005)

Two years after the 5035’s debut, the brand offered another annual calendar model, Ref. 5036 (1998), with a moon phase display replacing the 24-hour dial and a power reserve indicator below the XII, with the brand’s name moving to the lower part of the dial, between the moon phase and date apertures. Ref. 5036 was powered by calibre 315 S IRM QA LU, and its moon phase mechanism offered accuracy that required correction by one day every 122 years. The operating frequency remained at 21,600 vibrations/hour, and the power reserve at 48 hours.

The moon phase indicator will become a feature of practically all of Patek’s standard (without other complications added) annual calendars starting in 2005, with the release of Ref. 5146, which replaced the 5035 in the collection. The 5146 came in a slightly larger 39mm case, with the redesigned dial now featuring an even cleaner look. The Roman numerals gave way to baton indices and Arabic numerals at 3, 9 and 12, and the power reserve indicator below 12 got a simplified plus and minus signs display and no digits.

Also in 2005, the Ladies’ Annual Calendar Ref. 4936 saw the light of day, presented in a 37mm case, thus slightly smaller than the gentlemen’s version. Yet before that, in 2004, the Genevan watchmaker revealed another notable timepiece, the Gondolo Calendario Ref. 5135, and it’s a watch that deserves a few extra words.

The Gondolo collection is dedicated to non-round watches, including square, rectangular, and tonneau-shaped timepieces. Its name is a tribute to Patek Philippe’s former Brazilian distributor, Gondolo & Labouriau (1872–1927), which at one point accounted for a third of Patek Philippe’s entire production. The partnership led to the creation of the exclusive Chronometro Gondolo series, designed specifically for the Brazilian market.

The Gondolo Calendario Ref. 5135 stands out with its architectural, Art Deco-inspired tonneau-shaped case, measuring 39mm wide and 51mm long, complemented by a cushion-shaped bezel. The dial design features a distinctive layout with weekday, date, and month apertures arranged in an arched display between the 10 and 2 o’clock positions. A 24-hour sub-dial at 6 o’clock incorporates a moon phase indicator. The date window at 12 is framed in line with the arrow-shaped indices, while the dial’s surface contrasts beautifully with a two-tone finish – a circular azuré pattern in the centre and a satiné sunburst finish on the outermost part. The overall design is a captivating nod to both form and function.

The Gondolo Calendario Ref. 5135 introduced a new calibre developed from the base of the 324 movement, which itself was an evolution of the 315. The 324 brought several key improvements. First, it operated at a higher frequency of 28,800 vibrations per hour, ensuring a more stable rate and enhanced accuracy. Second, the efficiency of the automatic winding mechanism was significantly improved by enlarging the central rotor to generate more winding power. Third, the Gyromax balance wheel was refined, now featuring four spokes and reducing the number of tunable weights from eight to four.

Additionally, the 324 movement introduced several technical advancements: a new wheel tooth geometry, a reinforced winding wheel, lower-friction wheel arbour pivots and pinions, a redesigned minutes train bridge, and an asymmetric date train. The calibre 324 S QA LU 24H (324/205) was prominently displayed through the transparent caseback of the Gondolo Calendario Ref. 5135, with four corrector pushers – two on each side of the case – allowing for easy adjustments.

The distinctive arched aperture arrangement for the annual calendar display, first seen on the 2004 Gondolo Calendario Ref. 5135, returned in Patek Philippe’s notable creation of 2006. This brings us to a significant chapter in the history of Patek Philippe’s annual calendars – the introduction of the groundbreaking Flyback Chronograph Annual Calendar Ref. 5960.

2006 – The Flyback Chronograph Annual Calendar Ref. 5960

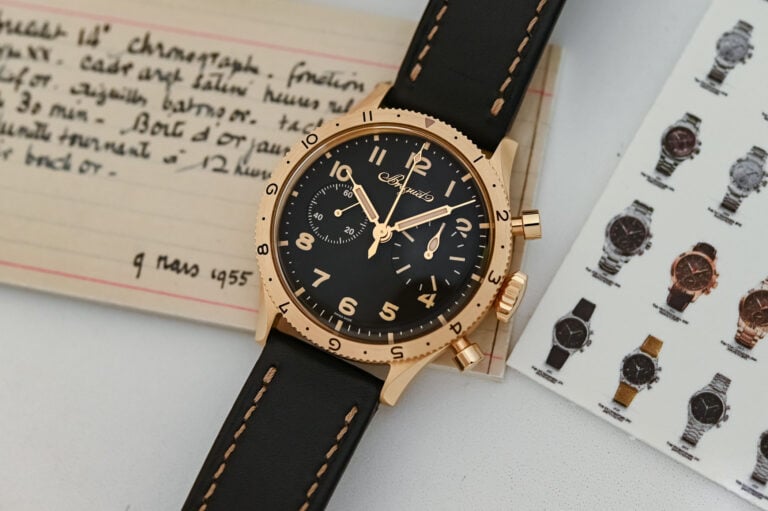

To understand the magnitude of the event, let’s go back in time and recall that the very first serially produced perpetual calendar chronograph was the manually wound 35mm Patek Philippe reference 1518, revealed in 1941. It was powered by the calibre 13”’130, based on a Valjoux ébauche, which, of course, is no surprise as Patek’s reliance on Valjoux, Lemania, and Victorin Piguet base movements on which the company developed many of its movements and most long-lasting chronographs is watchmaking trivia. So, it was a big deal when the manufacture was ready to reveal its new, first entirely in-house developed and produced automatic chronograph calibre CH 28-520 with the revolutionary Spiromax silicon-based balance spring in 2006. Patek presented the first results of its Advanced Research program aimed at mastering the qualities of silicon-based components in 2005; we’ll talk about it later.

The high-performance CH 28-520 flyback chronograph calibre featured the column wheel and vertical clutch configuration, used a gold central rotor for winding and had a better power reserve, providing between 50 and 55 hours of autonomy. CH 28-520 operated at 28,800 vibrations/hour, combining the Spiromax hairspring with a Gyromax balance, and was a technically improved, brought-forward movement that introduced a genuinely marvellous display of elapsed time. The conventional sub-dials for the small seconds and hours and minutes counters were no longer needed. The movement allowed just one to display elapsed hours and minutes and keep the chronograph running without remorse (in case you missed the running seconds feature). To showcase the newly developed movement, in an act that blended two distinct timekeeping mechanisms, Patek chose Ref. 5960 for its debut, and so CH 28-520 first appeared as calibre CH 28-520 IRM QA 24H. Fanfare, please.

The Flyback Chronograph Annual Calendar Ref. 5960, powered by the CH 28-520 IRM QA 24H calibre comprising 456 parts, debuted in a 40.5mm case with classic round chronograph pushers. When activated, the centrally mounted chronograph seconds hand, which shared its axis with the hour and minute hands, began its sweep. The single sub-dial at 6 o’clock featured two co-axially mounted hands, displaying elapsed minutes in two segments: 0 to 30 and 30 to 60 on the outer track and hours up to 12 on the inner circle. A small round window within the sub-dial indicated day or night by changing colours, adding practicality to the design.

The upper section of the dial displayed the arched apertures for the annual calendar, presenting day, date, and month data with ease. Just below the date window, a power reserve indicator provided an additional layer of functionality. Despite the abundance of information on the dial, Patek Philippe managed to preserve a clean and elegant layout, with eight full-sized baton hour markers contributing to its aesthetic and usability. This clarity and elegance became a hallmark of the 5960 and set a design standard that was successfully carried forward in other references.

2006 – Annual Calendar Ref. 5396 Calatrava

In 2006, Patek Philippe launched another annual calendar reference, the 5396, offering a completely different yet supremely elegant design. Housed in a 38.5mm Calatrava case, the watch featured a vintage-inspired sector dial that exuded classic sophistication. The day and month indicators were positioned within rectangular apertures at the top of the dial, just below the 12 o’clock marker. Meanwhile, the moon phase display was integrated into a 24-hour sub-dial below the centre, with the date window at 6 o’clock slightly overlapping.

For those wondering about the purpose of the 24-hour indicator, it’s important to remember that complicated calibres, like the one powering the 5396 (calibre 324 S QA LU 24H/303, consisting of 347 parts, many more than 280 typically needed for the standard perpetual calendar movement with a moon phase display), are tricky beasts and require precise handling. Adjustments to such intricate movements should only be made when the date change mechanism and moon phase switch are inactive. According to the owner’s manual, the safest time to adjust the watch using the correction pushers is around 6 AM, when the date and moon phase systems are dormant. This is where the 24-hour dial proves its practical value, ensuring the owner avoids damaging the delicate mechanisms during adjustments.

Before moving on to the important annual calendar timepieces revealed by Patek next, let’s touch on the promised subject of the Advanced Research Programme and the results it yielded relevant to our review.

Advanced Research References 5250, 5350 and 5450 (2005, 2006 and 2008)

The Patek Philippe Advanced Research webpage opens with a quote from Thierry Stern, the company’s current president: “In 2005, we decided to create a new concept of advanced research. The idea behind this concept was to show the world all the watchmaking knowledge and mastery of Patek Philippe.” This initiative was built upon a unique collaboration that began earlier, in 2002, between Patek Philippe, Ulysse Nardin (which introduced the Freak, the world’s first wristwatch with silicon escapement wheels, in 2001), Rolex, the Swatch Group, and CSEM (Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology). The watchmaking giants formed a consortium to secure a patent (EP1422436B1, granted in 2005 and expired in 2022) for the manufacturing of silicon hairsprings.

The consortium was driven by the shared belief in the material’s potential for revolutionising watchmaking. Silicon, being harder yet lighter than steel, non-magnetic, corrosion-resistant, shock-proof, and requiring no lubrication, was seen as an ideal material for critical watch components. Patek Philippe established its Advanced Research department to explore further and develop silicon applications in horology. The first watch to showcase the Advanced Research movement – self-winding calibre 315 S IRM QA LU SI with a new silicon-based escape wheel inside the traditional Swiss lever escapement – was the Advanced Research Annual Calendar Ref. 5250, presented as a limited edition of 100 in 2005.

The Ref. 5250 debuted in a 39mm white gold case with a silvered dial, mirroring the layout of the 5146, and introduced Patek Philippe’s mono-crystal silicon material, Silinvar, with its new escape wheel. A “cyclops” magnifying glass was placed on the sapphire crystal caseback, positioned above the escapement to highlight the innovation. This magnifier became a signature feature of future Advanced Research models, including the 2006 Ref. 5350 in pink gold. Powered by the 324 S IRM QA LU calibre, it featured the new Silinvar-based balance spring known as Spiromax, which improved consistency and accuracy. The Ref. 5350 was limited to 300 pieces and marked the widespread use of Spiromax in most new Patek Philippe calibres.

In 2008, the brand continued with the release of the Advanced Research Annual Calendar Ref. 5450P. This platinum timepiece, limited to 300 pieces, stood out with its salmon-coloured dial and introduced the Pulsomax silicon-based escapement, incorporating both the escape wheel and lever in Silinvar. This innovation significantly increased energy efficiency and eliminated the need for lubrication, marking another leap forward in horological technology.

2007 – Minute Repeater Annual Calendar Grand Complication Ref. 5033

In 2007, the annual calendar once again took centre stage as Patek Philippe featured this “lesser” complication in its prestigious Grand Complications collection. The Minute Repeater Annual Calendar Grand Complication Ref. 5033, first produced in a limited run of 10 pieces as a special order, might have seemed like an unconventional choice – perhaps even a daring experiment that raised a few sceptical eyebrows. However, it holds historical significance for two reasons: it highlights Patek Philippe’s storied tradition of crafting minute repeater mechanisms while incorporating a relatively new complication, the annual calendar, which had become emblematic of the brand’s modern innovation.

Patek’s history with repeater mechanisms dates back to 1839, with the manufacture continuing to produce them until the 1960s. After a brief hiatus, Patek reintroduced minute repeaters in the 1980s and, by 1989, began making them exclusively with in-house movements. This shift was marked by the introduction of the mini-rotor calibre R 27 PS, which would later serve as the foundation for the calibre R 27 PS QA, the movement that powers the Ref. 5033. It was introduced in a 38mm x 51mm platinum tonneau-shaped Gondolo case featuring a small sliding lever on the left to activate the minute repeater. The dial design echoed that of the Gondolo Ref. 5135, with its arched display for the calendar information in the upper section. However, unlike the 5135, Ref. 5033 omitted the moon phase and 24-hour sub-dial at 6 o’clock, replacing it with small seconds, resulting in a cleaner, more streamlined look.

2010 – Nautilus Annual Calendar Ref. 5726

One thing that is often attributed to the Annual Calendar’s “useful complication” is that, in a way, it started a trend for owners to actually wear fine mechanical watches daily rather than admire them as part of the collection. If so, then 120m water-resistant Nautilus Annual Calendar Ref. 5726, first released in 2010, is the epitome. To quote an early advertisement for “one of the world’s costliest watches made of steel”, it would “accompany you when you dive, or when the occasion is formal or festive, or when you set out to slay dragons in the boardroom”, it was “meant to be inseparable for life” with its owner. Daily wear, no less.

The Ref. 5726 debuted in a stainless steel 40.5mm case, with a thickness of 11.3mm, paired with an integrated leather strap. Its caseback and bezel were secured to the case middle by lateral screws at the iconic Nautilus “ears.” The dark grey gradient dial featured the signature horizontal embossed bars and an annual calendar layout familiar from the Calatrava Annual Calendar Ref. 5396. Two apertures beneath the 12 o’clock double index displayed the day and month, while the date window, positioned at 6 o’clock, was elegantly framed. The date aperture also overlapped a 24-hour indicator ring, which shared space with the moon phase display.

Powered by the self-winding calibre 324 S QA LU 24H/303, the Ref. 5726 relied on recessed corrector pushers for easy adjustment, just like the Calatrava Ref. 5396. A perfect blend of daily practicality and refined luxury, it captured the essence of the “useful complication”.

2011 – Annual Calendar Regulator Ref. 5235

In 2011, Patek Philippe introduced the bold Annual Calendar Regulator Display Ref. 5235, housed in a 40.5mm white gold case. This was the first wristwatch by Patek to feature a regulator-style dial layout, characterised by its exceptional clarity and legibility. The design includes a central sweep minutes hand to show minutes on the wide outermost track, with a sub-dial positioned just below the 12 o’clock mark for the hours, flanked by day and month apertures. A seconds sub-dial at 6 o’clock incorporates the date window. With its elegant retro-modern aesthetic, the dial was inspired by precision regulator clocks that watchmakers once used to fine-tune movements – a nod to the one in Mr Stern’s office, said to be the direct inspiration behind the Ref. 5235.

The bold new release by Patek Philippe was all about precision. It was powered by the ultra-thin, self-winding calibre 31-260 REG QA, developed through the Advanced Research Programme and operating at 23,040 vibrations/hour. With this infrequently encountered frequency, we shall start our quick look into this movement. The conventional operating frequency had to be recalibrated due to the inclusion of what Patek called “a complete collection of Silinvar components” in its introductory video. The three “maxes” – the Spiromax hairspring, Gyromax balance wheel, and Pulsomax escapement – work in unison to deliver precision timekeeping in the 31-260 REG QA calibre, achieving an impressive accuracy of -3/+2 seconds per day. The Spiromax hairspring is mounted on the top axle of the Gyromax balance wheel, while the Pulsomax’s pallet fork and escapement wheel provide the necessary impulse to the Gyromax.

These advanced components necessitated optimising the going train between the spring barrel and the Pulsomax escapement. As a result, the wheel teeth were redesigned to improve engagement and reduce friction, ensuring a constant flow of force with only 3% friction resistance. In line with the regulator display’s precision-driven nature, the movement also includes a hacking seconds feature, allowing for accurate time-setting.

The movement, featuring exceptional finishing and decoration with gold engravings and a mini-rotor, is visible through the sapphire crystal caseback. Despite the extensive use of Silinvar components, the caseback lacks the cyclops lens seen in earlier Advanced Research models, as by this time, silicon-based parts had become more common across Patek Philippe calibres.

2022 – Annual Calendar Travel Time 5326

The latest Patek Philippe creation to include the annual calendar mechanism is the Annual Calendar Travel Time Ref. 5326, which, as the name implies, also has a dual time zone display, making the watch twice as useful and very practical, for the movement is built so that the calendar indicators are synchronised with the local time hand. From admiration over the vintage and even military-inspired aesthetic of the exceptionally detailed, grainy textured anthracite dial and the watch’s exquisitely decorated 41mm x 11.7mm Calatrava-type case featuring a Clous de Paris hobnail guilloched pattern on the sides let’s delve into the works of the underlying calibre 31-260 PS QA LU FUS 24H (equipped with the Gyromax balance and Spiromax balance spring in Silinvar, with the off-centre platinum micro-rotor for winding and 38 to 48 hours of autonomy) and functions of this original timepiece.

Reading the watch’s indications is easy; the dial boasts a logical layout with the annual calendar data displayed in the apertures, the solid lume-filled hour hand indicating the local time and the skeletonised syringe-like hand indicating home time. The home time hour hand can be hidden under the local time hour hand when it is not needed. Both local and home time zones have designated and labelled day and night indicators; the moon phase, inside a small seconds sub-dial at 6 o’clock, completes the display.

The local time hand can be set backwards and forwards in one-hour increments using the crown in the middle position. The calendar indications move in sync with the local time hand (it is the local time hour wheel that drives the calendar), so the calendar is always displaying the local day, date, and month, all thanks to the added rocker and tension spring to the mechanism that pushes the date wheel in the direction needed. The home time is set with the crown in the outermost position, which also activates the stop-seconds mechanism for precise time-setting.

Remember how long the first PP Annual Calendar reference took to change the date? It took around four hours, and while the speed of advancing the display around midnight improved along the way, it still took an hour and a half. The new movement, as explained by the brand, “thanks to a cam system with partial toothing connected to the hour wheel, the 24-hour wheel executes its rotation in four phases instead of continuously: 180° rotation in 3 hours (toward midnight), 9 hours of standstill, 180° rotation in 3 hours (toward noon), 9 hours of standstill”. This improves the coordination of the calendar switching phase with local time and now makes the switch take about 18 minutes.

Engineering solutions “to optimise the efficiency, precision, durability, safety, and operating convenience of the calibre 31-260 PS QA LU FUS 24H movement” resulted in eight patent applications, among them the forward/backward mechanism for the Annual Calendar (EP 3776095A1) that allows the transition from the 30th to the 1st and from the 1st to the 30th without desynchronising the date so that the owner can easily switch the time zone forward or backwards with the winding stem.

The user-friendliness and practicality of the Annual Calendar Travel Time Ref. 5326 deserve commendation. While the Minute Repeater Annual Calendar Grand Complication Ref. 5033 bridges the brand’s past and present, much like the Annual Calendar Regulator Display Ref. 5235, the 5326, looks towards the future. This forward-thinking approach is evident in the innovative materials and solutions employed in the calibre 31-260 and in appealing to a new generation of buyers. It’s thrilling to anticipate how the annual calendar complication will evolve and what exciting new models will emerge next.

Conclusion

If you’ve made it to the end of this overview, I truly appreciate your time and hope the wealth of information sparked interest rather than fatigue. Annual calendars, more accessible than their perpetual siblings, offer a perfect blend of practical functionality, aesthetic appeal, and mechanical mastery. When Patek Philippe sought to create an annual calendar watch in the 1990s, it was an act of genius which introduced a complication that has since become a favourite among many watch enthusiasts. Today, we celebrate this relatively modern invention as one of the most practical and enjoyable timepieces to own and wear.

This list should be seen as an evolutive overview, as the most important steps in the history of the annual calendar complication at Patek Philippe. There are many more Patek watches equipped with an annual calendar function. We can, for instance, list some of them covered in these articles:

- An overview of a special combination of complications, the annual calendar chronograph

- the Patek Philippe Annual Calendar Chronograph 5905P, a bolder, larger and more modern take on the 5960

- the Patek Philippe Chronograph Annual Calendar 5960G with a vintage look

- the classic Patek Philippe 5396R Annual Calendar, a streamlined version in a Calatrava case

- the Patek Philippe Annual Calendar Regulator 5235R, with a rose gold case

- the Patek Philippe Nautilus Annual Calendar 5726A, here in steel with a steel bracelet

- the Patek Philippe Annual Calendar 4947A, a compact and classic version in stainless steel

- the Patek Philippe Chronograph Annual Calendar 5905/1A, a sportier take with a green dial in steel

- the Patek Philippe Aquanaut Luce Annual Calendar 5261R, the first Aquanaut with this complication

For more details, please visit Patek.com.

2 responses

What an excellent article. I’m a huge fan of the annual calendar complication and think it gets rather less attention than it deserves – the 5146 is a great watch. Such a practical complication, being relatively easy to reset if needed (unlike most perpetuals). Fantastic to see the attention deficit redressed by this deep dive. It will be interesting to see how Patek continues the development of this signature complication. Like all complications, legibility is key and love it or loath it, the Cubitus offers a LOT of dial/case real-estate for additional complications. Blancpain played a similar tactic with the 43mm Bathyscaphe – too much negative space for a three-hander, but perfect for the addition of a QA.

Great article! I read it while watching my 4947/1A change the date from 30th to 1st. Indeed it is a both practical and easy to handle complication.