The IWC Doppelchronograph 3711, the First 7750-Based Split-Seconds Chrono

One of the best examples of a no-nonsense, rugged and yet mechanically important watch, that you still can get at a bargain price.

Welcome to The Collector’s Corner, a new series of stories about watches from the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, and maybe the occasional watch from the 1970s. You could say, ‘post quartz-crisis watches’ or watches from the renaissance of high-end watchmaking or ‘youngtimers’ or ‘neo-vintage’. Whatever you (or we) call these watches, there are so many very cool watches from the aforementioned era that really deserve some renewed attention and that’s exactly what we will do in the Collector’s Corner instalments. We describe why we think they’re cool and why they deserve your attention!

The ‘neo-vintage’ watches, despite their own contributions to horology, remain overlooked and (often) under-appreciated and are just entering the cusp of vintage-dom. To understand the significance of this era, it’s important to do a quick recap of the quartz crisis; so much has already been said on the subject that I promise to keep it short! And then, we’ll start this series by looking at an important watch, one that truly deserves your attention, and one that offers a lot of mechanical pleasure for a relatively accessible price (for now…), the IWC Pilot’s Watch Doppelchronograph 3711.

The world’s first commercially viable quartz wristwatch, the Seiko Astron, was introduced in 1969. With the promise of cheap, reliable, and accurate timekeepers from the East, the values of traditional mechanical watchmaking – not just Swiss – were turned on their head. The watch models that are credited with saving the mechanical watchmaking industry are well-known to all and were designed by a certain Gerald Genta. The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and the Patek Philippe Nautilus ushered in a new age where watchmaking was less about timekeeping and more about the preservation of generations of tradition, heritage, and art. After the quartz crisis led to a culling of the herd in the Swiss watch industry, the two decades that followed were a time of rebirth and re-discovery for many companies. It’s crazy to think that mechanical watchmaking went from being on the brink of obsolescence to being a celebration of complications, all in the span of some 20 years! By the early 1990s, in fact, watch companies were engaged in a competition to see who could manufacture the most impressive uber-complicated watch.

You’re probably asking yourself what all of this has to do with IWC… after all, this is supposed to be an article about IWC, right?

IWC after the quartz crisis

Since its founding in 1868, IWC’s engineering-driven approach manifested itself in a series of technological innovations. In 1885, IWC designed the first watches with a digital hours and minutes display (the so-called Pallweber system). IWC’s first “Special Pilot’s Watch”, which featured a rotating bezel with a triangular luminous index to aid pilots in registering takeoff times, was launched in 1936. The 1940s saw the development of a robust and efficient pawl-based winding system by Technical Director Albert Pellaton. This technological focus also led IWC to participate in the collaborative effort of Swiss watchmaking companies to develop a Swiss quartz movement in the late 1960s, the same technology that would leave the company floundering for direction in the 1980s.

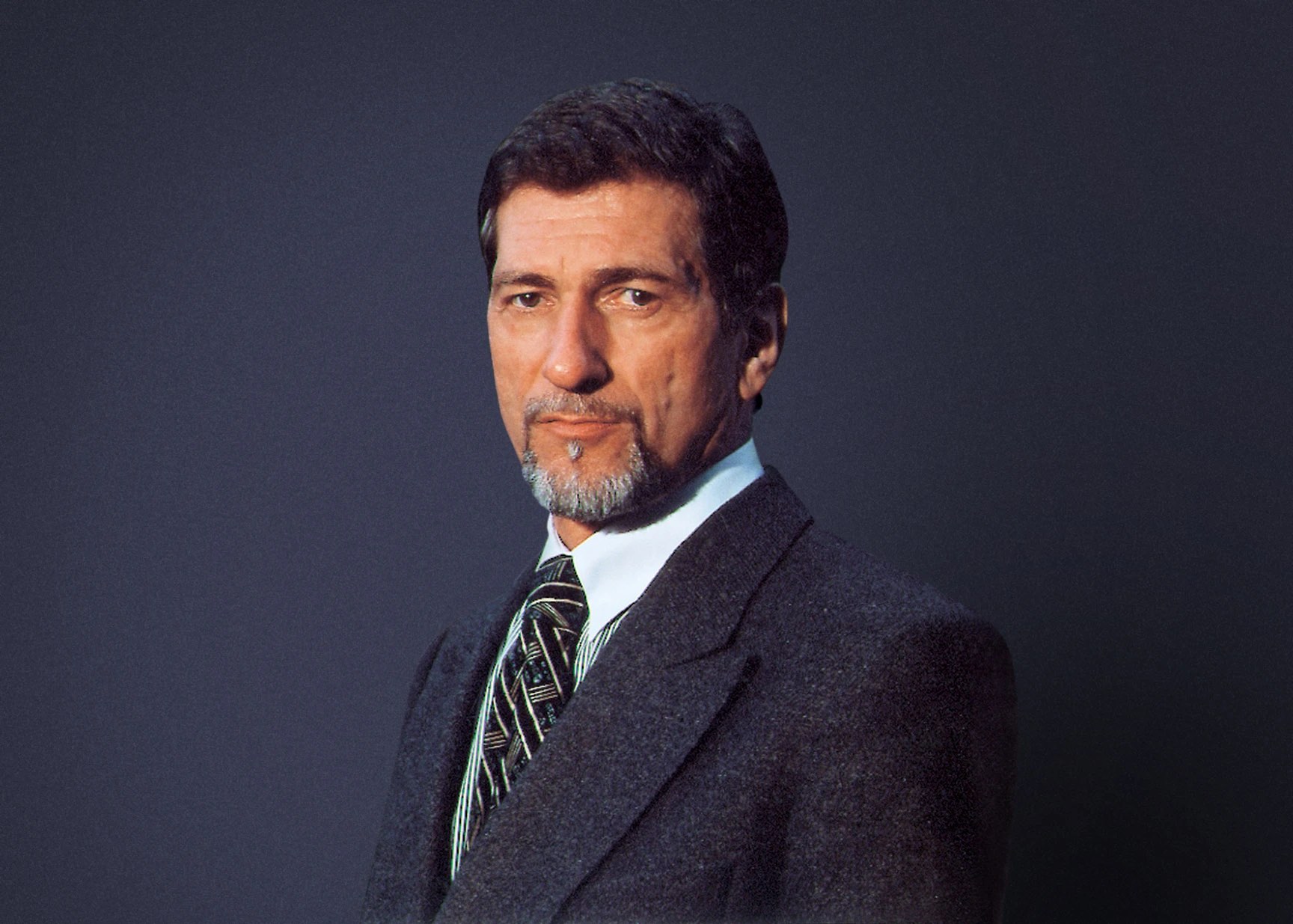

The history of IWC, much likes the fates of its now-sister Richemont companies A. Lange & Söhne and Jaeger-LeCoultre, is intertwined with one Günter Blümlein. Born in the shadow of a war-ravaged Germany in 1943, Blümlein benefited from the rapid recovery and reconstruction in Germany known as the Wirtschaftswunder. In 1980 Blümlein, an engineer by trade became the head of Les Manufactures Horlogères, an umbrella company that the German precision instrument company VDO Adolf Schindling AG formed to manage its newly acquired portfolio of two watchmaking companies: IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre.

For a full look at the impact Mr Blümlein had on IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and A. Lange & Söhne, and on watchmaking as a whole in recovering after the quartz crisis, check out our in-depth in-depth feature remembering Mr Blümlein, 20 years after his passing.

The year Blümlein took over LMH marked the beginning of the great turnaround for IWC and it’s important to devote some words to understand the impact he had on the company. Under the visionary Blümlein, IWC was marketed as an unabashedly masculine manufacturer of no-nonsense timepieces. Engineering was put front and centre. IWC watches were to be timekeepers for the young and adventurous crowd – it was a clean break from the fuddy-duddy, old-fashioned IWC of the past.

Building on IWC’s experimentation with exotic case materials, such as the original IWC-Porsche Design compass watch in aluminium, IWC experimented with watches in titanium and ceramic, and sometimes even a combination of the two.

Blümlein also had the foresight to make the iconic Flieger watch available to the general public. Formerly, the Mark XI, which had been in production since 1948, was only offered to military and civilian pilots. The 1989 Pilot’s Watch range was finally made widely available with the introduction of the reference 3741 and, reflecting the predominance of quartz technology at the time, powered by a JLC meca-quartz movement.

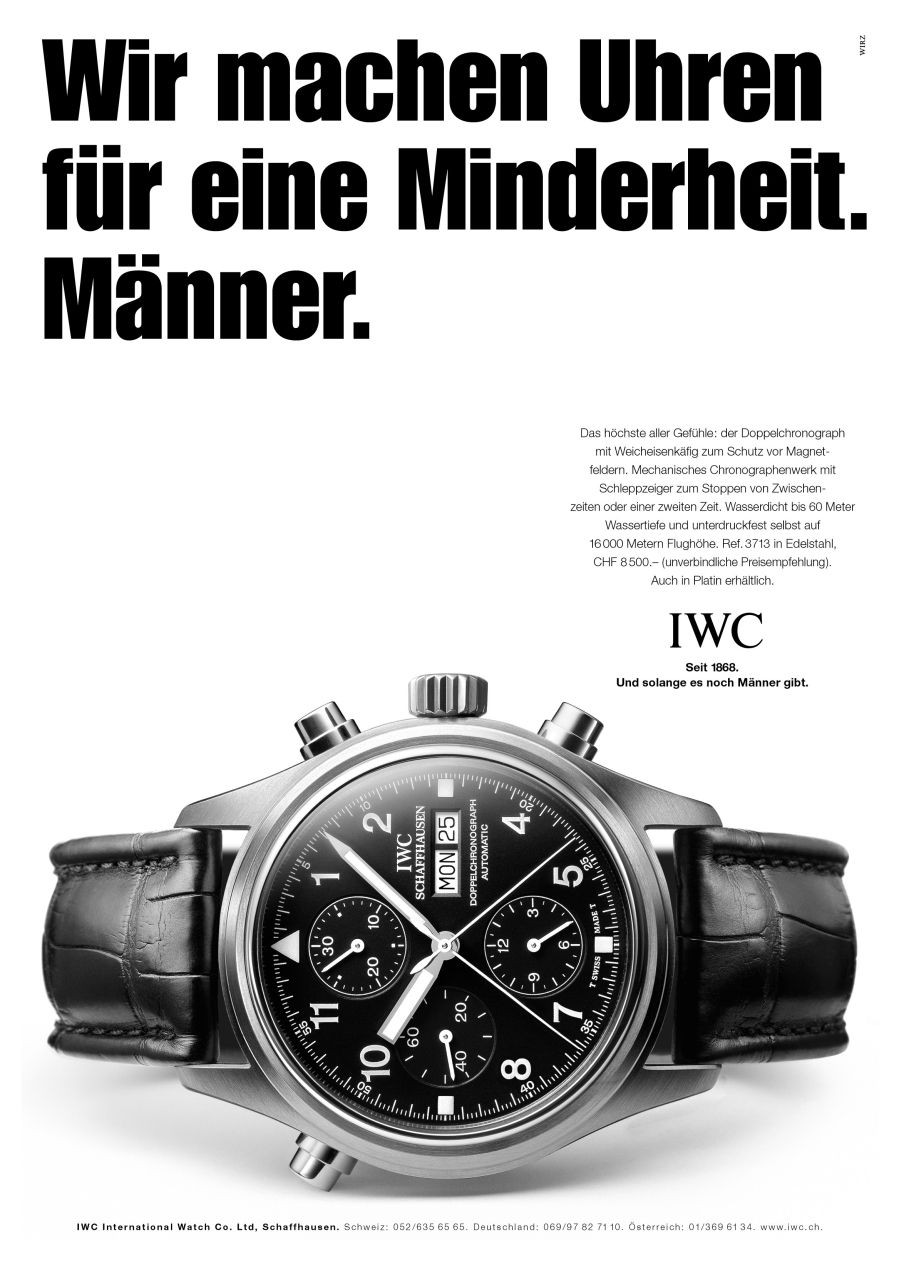

At the same time, Blümlein doubled down on mechanical watchmaking and pioneered the concept of accessible, modular complications. First came the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Chronograph wristwatch, which used Kurt Klaus’s mechanically programmed calendar module on top of the ubiquitous Valjoux 7750 that was already widely being used in the company’s line-up. And second, with the Doppelchronograph ref. 3711, the world’s first modular split-seconds chronograph complication was born. Two years later, IWC released the Il Destriero Scafusia, “The Warhorse from Schaffhausen” to commemorate the 125th anniversary of its founding. This 125-piece grand complication, a tourbillon, minute repeater, perpetual calendar, split-seconds wristwatch took the idea of the modular complication to new heights, and is actually based on the Valjoux 7750!

The IWC Doppelchronograph 3711 – The Basics

The IWC reference 3711 is a 42mm watch that stands 16.5mm thick, thanks in part to the modular rattrapante complication and the soft-iron inner caseback that protects the movement against magnetism. The case in all metal variants (along with steel, the 3711 was offered in yellow gold and platinum) is brushed, and all three pushers are pump-style. The yellow gold variant, however, has a more upscale appearance – the upper lug hoods are polished. Also, instead of a matte finish, the dial is finished in glossy black lacquer with applied golden indices, golden-coloured day and date discs, and gilt printing.

Two dial variants were offered, white and black – all were manufactured before the widespread use of Luminova and have tritium lume plots at the quarters. The more common black dial is finished with a matte texture and the hour numerals are printed in high-contrast white. For increased legibility, the day-date complication at 3 o’clock features black on white printing. A few noticeable features of this Doppelchronograph 3711 are the emblematic “fish crown” (screw-down) as a testimony of the case’s water-resistance and the presence, on this reference only, of an ultra-domed sapphire crystal. The caseback, screwed on the case, proudly shows the mention “DER DOPPELCHRONOGRAPH”.

Inside the case is the automatic calibre 79030 (later the 79230, upon the switch to Triovis regulation). The 79030 is based on a Valjoux 7750 ébauche with a modular split-seconds chronograph mechanism designed by Richard Habring. He significantly simplified what is otherwise a notoriously difficult and expensive complication to create the world’s first serially produced rattrapante chronograph calibre. The 79030 has a 3Hz beat rate, bi-directional winding, and a healthy 44-hour power reserve.

Why should you consider the IWC Doppelchronograph 3711?

The Doppelchronograph speaks to me on many levels. When you look at the watch and hold it in your hand, you realize this is far removed from the dainty, precious metal toys that most split-seconds chronographs tend to be. The Doppelchronograph screams “tool watch”. It is big and, in the variant I’d go for, is made entirely in brushed stainless steel. The all-brushed finish invites daily wear and the watch’s reassuring heft is comforting – you know that it can take a knock or two and won’t miss a beat! There’s nothing more vexing than owning a watch that you’re afraid to wear frequently because you worry it isn’t up to the rigours of daily life.

There’s something about these no-fuss, bang-them-up watches that speaks to me. Looking at the Doppelchronograph 3711, I get the same feeling as when I hold a well-loved Submariner 14060 or a Speedmaster Professional… or, taking the analogy away from the world of watches, like holding a pair of battered and worn Redwing boots. These watches take me back to the days when a watch was just a watch, an instrument for telling the time, not the safe queen, status symbols of the modern world. Granted, I wasn’t even alive to witness those days, but the sheer “utilitarian-ness” of the watch appeals to me at an emotional level that I can’t quite explain! You look down at the dial of the Doppelchronograph and you’re struck by the sheer legibility of it. White printing on a matte black base makes for incredible contrast – the day and date are reversed: once again, legibility is the name of the game! It also has to be said that the Doppelchronograph is instantly recognizable as an IWC – even though IWC was not alone in manufacturing the first Flieger watches, it is the company people automatically associate with the look.

Being a technical-minded enthusiast and a fan of all things chronograph, I can’t deny that the historical significance of the 3711 appeals to me: in owning the Doppelchronograph, you are buying into a chapter of complications history. The Doppelchronograph was the first step toward the democratization of high complications – a trend that continues today with brands such as Horage recently unveiling a tourbillon for under CHF 10,000. The genius of Richard Habring’s rattrapante system is that it is based on the readily-available Valjoux 7750 base movement. By extending the same philosophy of ease of machining and assembly to the rattrapante, Habring created one of the most durable and affordable split-seconds chronographs on the market.

Lastly, let’s come to the value proposition. The Doppelchronograph was manufactured only for four brief years, between 1992 and 1995. It would later be replaced by the 3713, using a flat sapphire crystal and, for most of the production run, Super-LumiNova on the dial – with the exception of early versions of the 3713, still using tritium markers.

That short production run, combined with its flagship-status retail price at the time of its release, make it a relatively uncommon watch. Nonetheless, it can now be had upwards of just over EUR 5,000 in stainless steel, certainly not a lot of money for one of the greatest chronograph innovations in watch history. The Double Chronograph is an IWC icon that lives on today in the form of the ref. IW371815, the Pilot’s Watch Double Chronograph Top Gun Ceratanium. If anything, this speaks to the timelessness of Richard Habring’s groundbreaking innovation – it is still relevant 30 years after its introduction.

After all, there has to be a reason the caseback of the original read “DER DOPPELCHRONOGRAPH”, German for the double chronograph. Not just any double chronograph, but the double chronograph!

2 responses

Not sure $6-$7k would be considered a “bargain”. Also, at 42mm with pushers on both sides, it’s a bit large. I’d say the regular chrono version (iW3706) at 39mm is therefore a better option, and slightly more in the “bargain” category.

@Tim Eckel: On the contrary I would argue 42mm is on the small side these days (it’s the smallest on my shelf, alongside the 43mm ‘little’ Big Pilot, a 44mm Ulysse Nardin Torpilleur Military and a 43mm Tudor Black Bay Bronze slate dial) but the heft makes up for the lack of width to some extent. I’ve had a couple of 39mm 3706 models but sold them as they were too small on my 20cm wrist. The Doppel is the one to have, and it is indeed very much a bargain (still) when you consider the movement is so special. The 3706 is pretty humdrum by comparison.