A Closer Look at Laurent Ferrier’s Natural Escapement and the Micro-Rotor Movement

This superb movement is a marvel of mechanics regulated by a natural escapement.

Today, for our latest in-depth video, we’re going technical. This is what MONOCHROME is all about, after all. Sharing the knowledge behind fine horology and understanding how our beloved mechanical watches actually work. Today’s topic is one dear to our hearts, as it combines everything we love in fine watchmaking: high-end finishing, mechanical ingenuity, profound historical references and a complex mechanical device that aims to enhance precision. It is time for us to dive into one of the most spectacular movements currently in production, Laurent Ferrier‘s micro-rotor calibre, and to understand how its natural escapement works.

Horology 101 – What is an escapement?

Before we even approach the concept of the natural escapement, we need a concise reminder about the escapement itself. What is the role of the escapement in a watch? The escapement is one of the most critical parts of a watch, the brain of the movement, or its heart, as some might say. It is the device that counts the passage of time that regulates the tic-tac of the movement. It commands the speed at which the energy from the mainspring barrel is released. It works in conjunction with the oscillator (balance + hairspring), giving impulses to power it. In return, it is regulated by the oscillator. Its role is critical in the quest for a movement’s perfect precision, stability and durability.

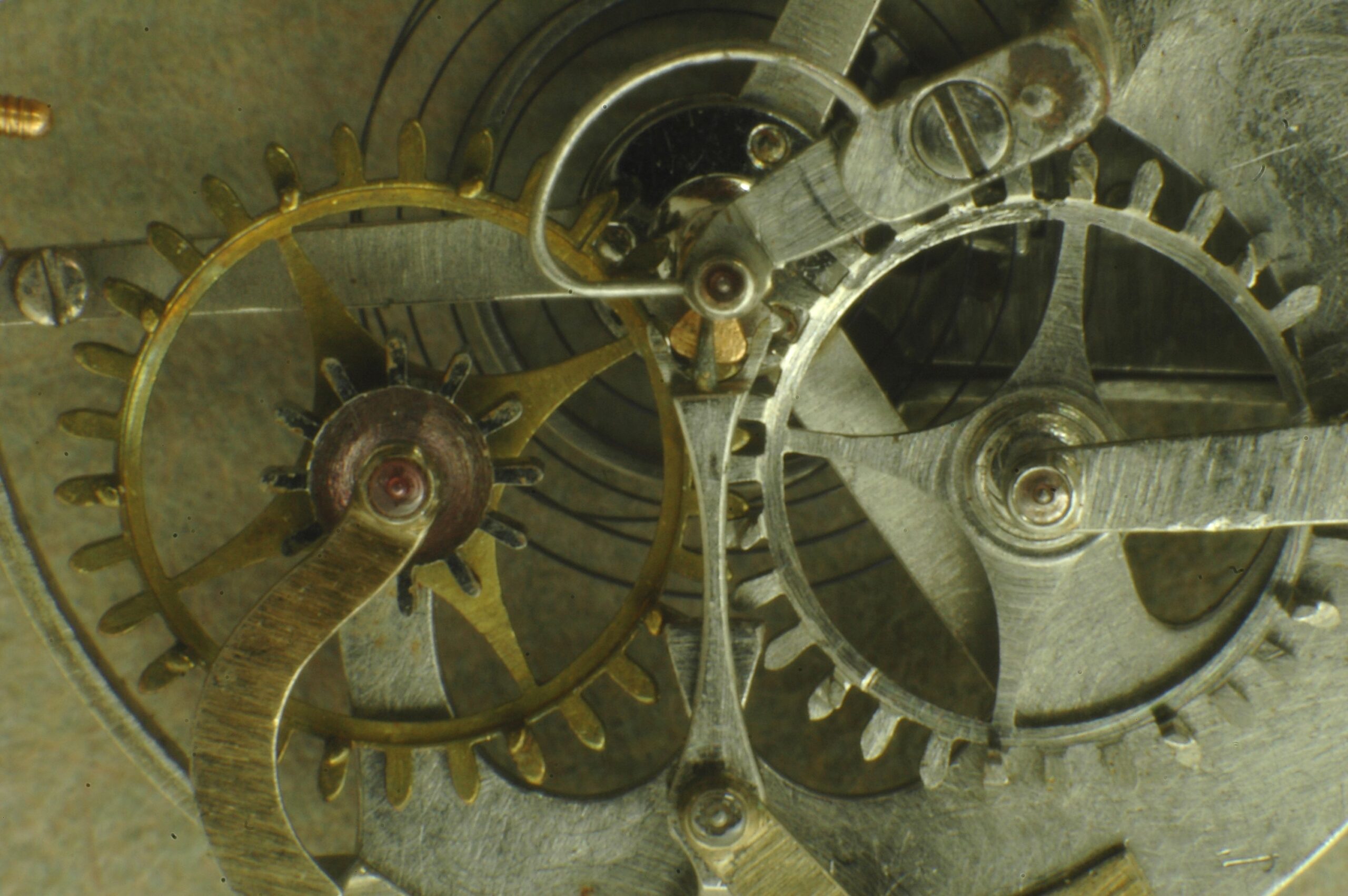

Invented by the English horologist Thomas Mudge in the middle of the 18th century, the Swiss lever escapement is currently used in almost all of the mechanical watches we have today. Its supremacy lies in its unparalleled simplicity, making it extremely economical. Although it is known for its outstanding reliability, the Swiss lever escapement has low efficiency, transmitting to the oscillator barely more than a third of the energy it receives from the mainspring.

The Swiss lever escapement is also appreciated for its self-starting capacity, yet it comes with the inherent need for lubrication. Indeed, the sliding motion of the pallet jewels creates a high level of friction. Not only does this affect the escapement’s efficiency, but it also affects the precision of the movement over time as the oils degrade. This is why, for as long as horology has existed, watchmakers have challenged the concept of the Swiss lever escapement, trying to find more efficient solutions.

Breguet’s idea, The Natural escapement

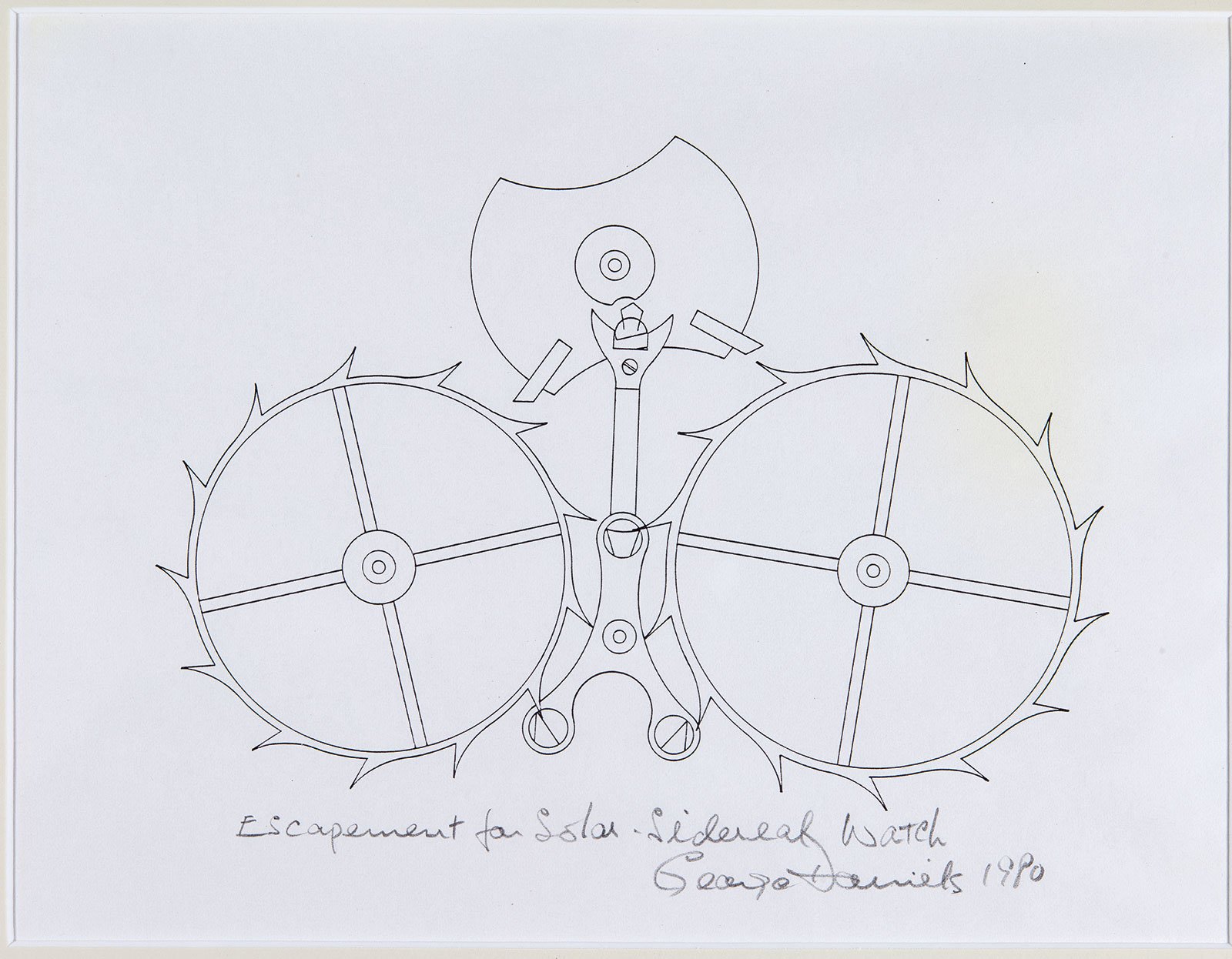

One of the oldest yet most fascinating solutions to compensate for the flaws of the lever escapement has to be credited to one of the greatest names in horology, Abraham-Louis Breguet. His idea was to combine the self-starting capacity of Mudge’s 1755 lever escapement with the frictionless operation of another exotic solution, the detent escapement – which predates the lever escapement, arguably invented in 1748 by clockmaker Pierre Le Roy, refined by Englishmen Arnold and Earnshaw. Breguet thus conceived the so-called natural escapement.

In his quest to improve chronometry, Breguet’s idea was to create an escapement incorporating two escape wheels. The escapement is said to be ‘natural’ because the impulses are transmitted from the escapement wheels to the balance wheel as directly as possible. There is no sliding friction, which is one of the main weaknesses of the Swiss lever escapement, and they do not require lubrication. Operating in alternation, these give two impulses per oscillation, one in each direction.

However, Breguet faced major issues in the development of the natural escapement, mostly related to the lack of technology, the poor quality of the materials and the inability to achieve the high tolerances required for such a complex mechanism – there was some play between the gears and backlash. For this reason, Breguet and other contemporary watchmakers who tried to make the natural escapement feasible, even though theoretically superior, had to return to the classic Swiss lever system.

Modern days, the return of the double-wheel escapement

The resurgence of independent watchmaking that followed the quartz crisis brought back some of the great horologists under the spotlight, with the work of A.L. Breguet being studied by men such as George Daniels and Derek Pratt. Daniels, while researching alternative escapements – which gave birth to the all-time famous co-axial escapement – and solutions to reduce the sliding friction of the Swiss lever, came to rediscover Breguet’s natural escapement.

Daniels tried to improve Breguet’s solution, implementing his own vision within the movements of the Space Traveller I and Space Traveller II. One of the tweaks was to remove the direct connection between the two escape wheels, creating two sub-movements with each its own mainspring, gear train and escape wheel. As such, the issue of play found in Breguet’s idea was cancelled, as well as the need for escape wheels with pillars. Essentially, Daniels created a double-wheel escapement, not a fully functional natural escapement the Breguet way.

Derek Pratt, a friend of Daniels and an equally genius horologist, adopted Breguet’s concept for himself more respectfully. He did not use separate gear trains. The idea, explained in a Horological Journal article from 2009 – which you can read here – came from another Breguet concept, the tourbillon. Found in the Double-Wheel Remontoir Tourbillon of 1997, this watch featured double escape wheels within the tourbillon cage with separate remontoir springs into each escape wheel.

Modern technologies made it possible for watchmakers to reduce tolerances to the max and thus to adapt Breguet’s natural escapement to wristwatches and for it to perform its ballet, as conceived by Breguet. Kari Voutilainen, François-Paul Journe, Charles Frodsham, Bernard Lederer, and Ulysse Nardin, with its dual impulse escapement, all have been inspired by Breguet and managed to produce natural escapements thanks to silicon, LIGA, DRIE and CNC machining.

Laurent Ferrier’s Natural Escapement

Laurent Ferrier is known for crafting some of the most elegant wristwatches, classics with a twist and superbly finished movements. In 2009, after a long career with Patek Philippe, he founded an eponymous brand with his friend Francois Servanin. The first watch presented by the brand was a tourbillon equipped with a double hairspring. The second model, released a year later, was fitted with the brand’s proprietary micro-rotor movement. And the latter wasn’t only spectacular in its design and decoration, it also came with a fully functioning take on the natural escapement, the way Breguet conceived it… something that somehow doesn’t get the recognition it should.

Developed together with movement specialist La Fabrique du Temps (now owned by LV), the Laurent Ferrier micro-rotor returned to the original idea of A.L. Breguet, where the two escape wheels mesh, as the first escape wheel not only plays its escapement role but also drives the second one as part of the gear train – the LF micro-rotor notably features only a single mainspring and gear train, not two like Daniels’ concept.

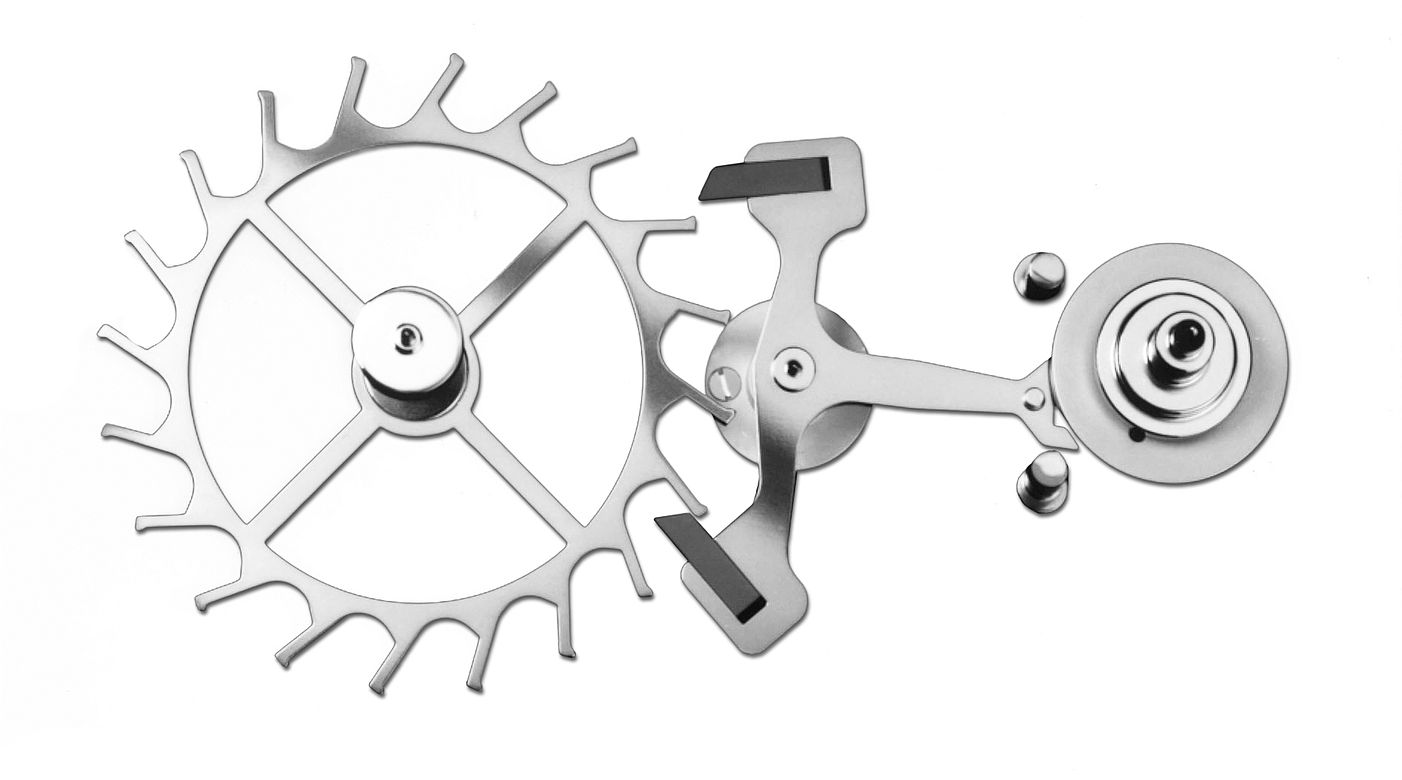

The geometry of these two escape wheels incorporates vertical teeth or pillars that replace the pallets of a standard escapement. They give the impulse directly to the balance. They also rest on the anchor while waiting for the next impulse to the balance wheel. The conception of this complex natural escapement was made possible thanks to modern technologies. It relies on LIGA technology (Lithographie, Galvanoformung, Abformung) to create escape wheels made from nickel-phosphorus as a single part on two planes. With this design, LF’s natural escapement could well be the closest to the original designs of Breguet, and in all fairness, this is something that should be much applauded.

These modern technologies were crucial in making the natural escapement viable, mainly because a natural escapement requires ultra-precise and light components (low inertia is crucial for the natural escapement) with minimal friction. This explains why there are no jewels in the escapement of this Laurent Ferrier micro-rotor movement, contrary to the pallets of a standard Swiss lever escapement. The detent lever is made from silicon, again eliminating the need for lubrication and also allowing for precise geometry.

One of the benefits of this natural escapement, given the low level of friction, is its high efficiency compared to a traditional lever escapement. Laurent Ferrier’s micro-rotor calibre offers 72 hours of power reserve, which is substantial considering the use of an off-centred micro-rotor within the movement, something that doesn’t allow for a large barrel and with a long mainspring.

A movement with spectacular finishing

Besides its technical superiority and the simple fact that we’re looking at one of the only working attempts to bring Breguet’s original natural escapement to life, the micro-rotor movement of Laurent Ferrier is also a marvellous piece of horology, a movement that has been handsomely designed and finished. Just like Ferrier’s watches, it isn’t overly demonstrative. It doesn’t try to do too much, but a trained eye will see what matters.

The micro-rotor movement is first and foremost a highly elegant movement, with pleasant shapes for the bridges, large sinks for the jewels and beautifully shaped edges that follow the position of the jewels. A closer look reveals the beauty of the decoration, which is done by hand, including large hand-polished bevels, internal angles and black polished steel parts. The balance bridge and the micro-rotor bridge are, without a doubt, the two most spectacular parts of this movement. Go deeper, and you’ll see that nothing has been left on the side… But then again, it’s never overly spectacular.

This superb calibre has been instrumental in the development of Laurent Ferrier as an independent watchmaking brand. It powers some of the brand’s most appealing models, such as the Galet or Classic Micro-Rotor watches, the more original Square model that you can see in the video or the Traveller’s watch.

For more details, take a look at the video at the top of this article and visit laurentferrier.ch.

6 responses

What a beautifully instructive article and video, thanks so much guys!

And all that with that level of restraint.

A lovely read!

Great article. Will you ever cover the Charles Frodsham Double Impulse Chronometer?

@ Spangles – we’d love to do that, yes. We have to find a way to get our hands on an example, however, which isn’t the easiest. But we’ll try 🙂

Thanks for documenting more of Laurent Ferrier which never gets as much attention as they deserve.

+1 on covering the Charles Frodsham Double Implulse.