Everything You Should Know about the Legendary Valjoux 7750 Chronograph Movement

The why and how a not-so good-looking “tractor” chronograph movement, born half a century ago, continues to influence the watchmaking world

The ETA Valjoux 7750 chronograph movement is well-known in the world of watchmaking for being tough, reliable, and versatile. Since it was first introduced in the early 1970s, it has gained a strong reputation for being accurate and long-lasting, which has made it a favourite chronograph calibre among both watchmakers and enthusiasts. In addition, the 7750 is built in a way that makes it relatively easy to service and update so that it can be used as a base for different kinds of upgrades and changes. Because of this, it’s been used in thousands of watches, from affordable to truly high-end ones, showing how versatile and appealing it is, but also how influential it has been for the industry. We gladly mark the 50 years of the Valjoux 7750 by offering a look at its origins, characteristics and importance to the industry.

Valjoux – 1901 to 1983, from Reymond Freres SA to ETA

The most better-known and pervasively present chronograph movement was created by a company founded in 1901 by brothers John and Charles Reymond. Initially operating as Reymond Frères SA (until 1929), the company used the brand name “Valjoux” (short for Vallée de Joux) and a cursive R for Reymond within a shield logo starting in the 1920s. In 1929, when the Reymond brothers’ sons, Marius and Arnold, took over, the company was renamed Valjoux SA and already enjoyed the status of a renowned specialist in chronographs, producing both ébauches complete movements and – the iconic Valjoux Calibre 22, introduced by Reymond Frères SA in 1914, remained in production for 60 years until 1974.

When Marius and Arnold got hold of Valjoux SA, the movement manufacturing business was transforming. In 1931, Ebauches SA, initially formed in 1926 by three watch movement manufacturers, joined forces with several other Swiss companies to create ASUAG, a larger holding company. The following year, in 1932, Eterna became part of this conglomerate but was divided into two entities: Eterna SA, responsible for producing complete watches, and ETA SA Fabriques d’Ebauches, dedicated to manufacturing watch ébauche movements. Over the years, many other companies were absorbed into ASUAG/Ebauches SA, including Valjoux SA in 1944. In 1979, A. Schild merged into ETA, making it the largest ébauche manufacturer in the world. Three years later, FHF, the owner of Landeron, was incorporated into ETA along with other ébauche makers. Finally, in 1983, Ebauches SA discontinued operations and companies such as Unitas, Peseux, and Valjoux, joined ETA. Notably, a decade before this consolidation, Valjoux SA introduced the 7750, the most ubiquitous self-winding chronograph movement.

Context and origins – the creation of the Valjoux 7750

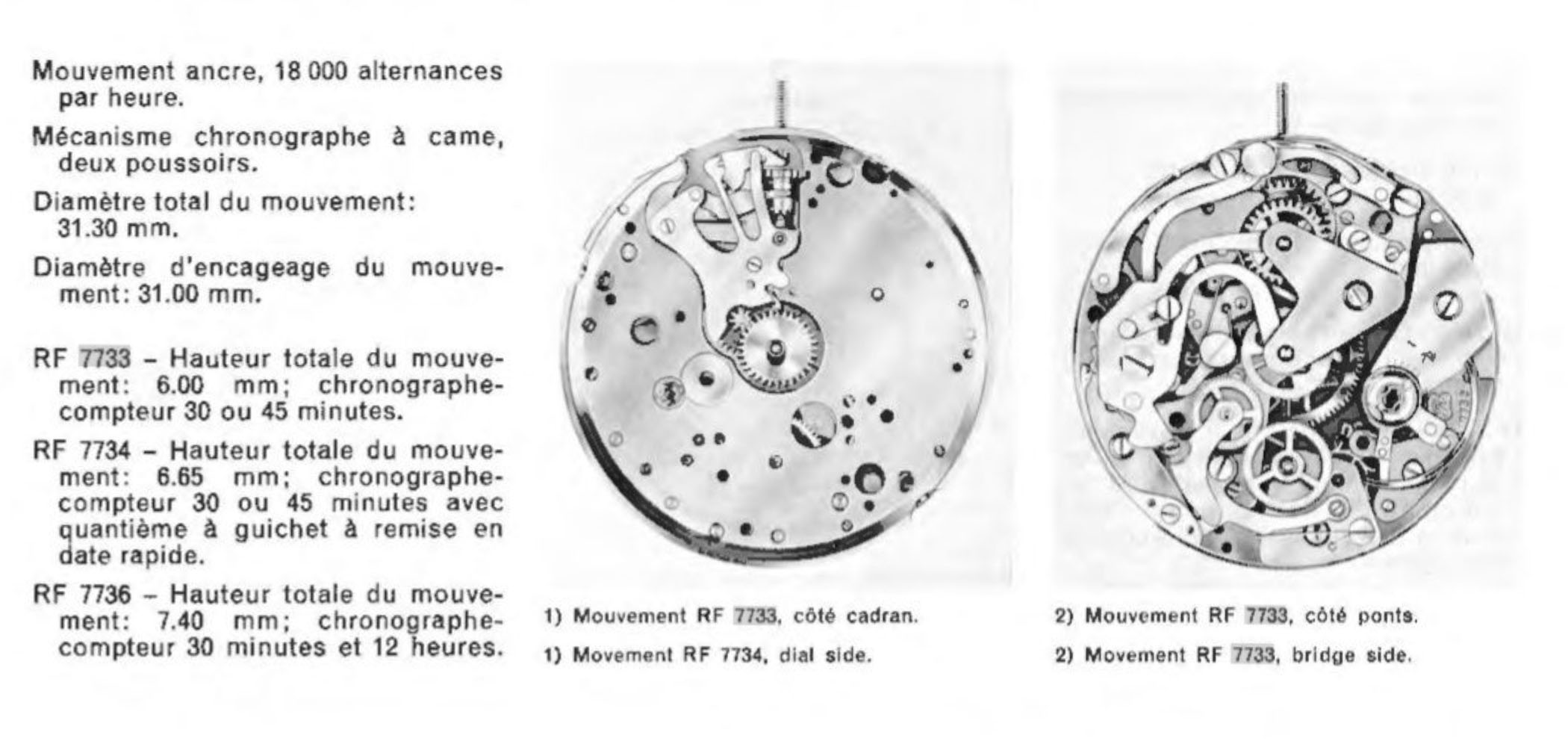

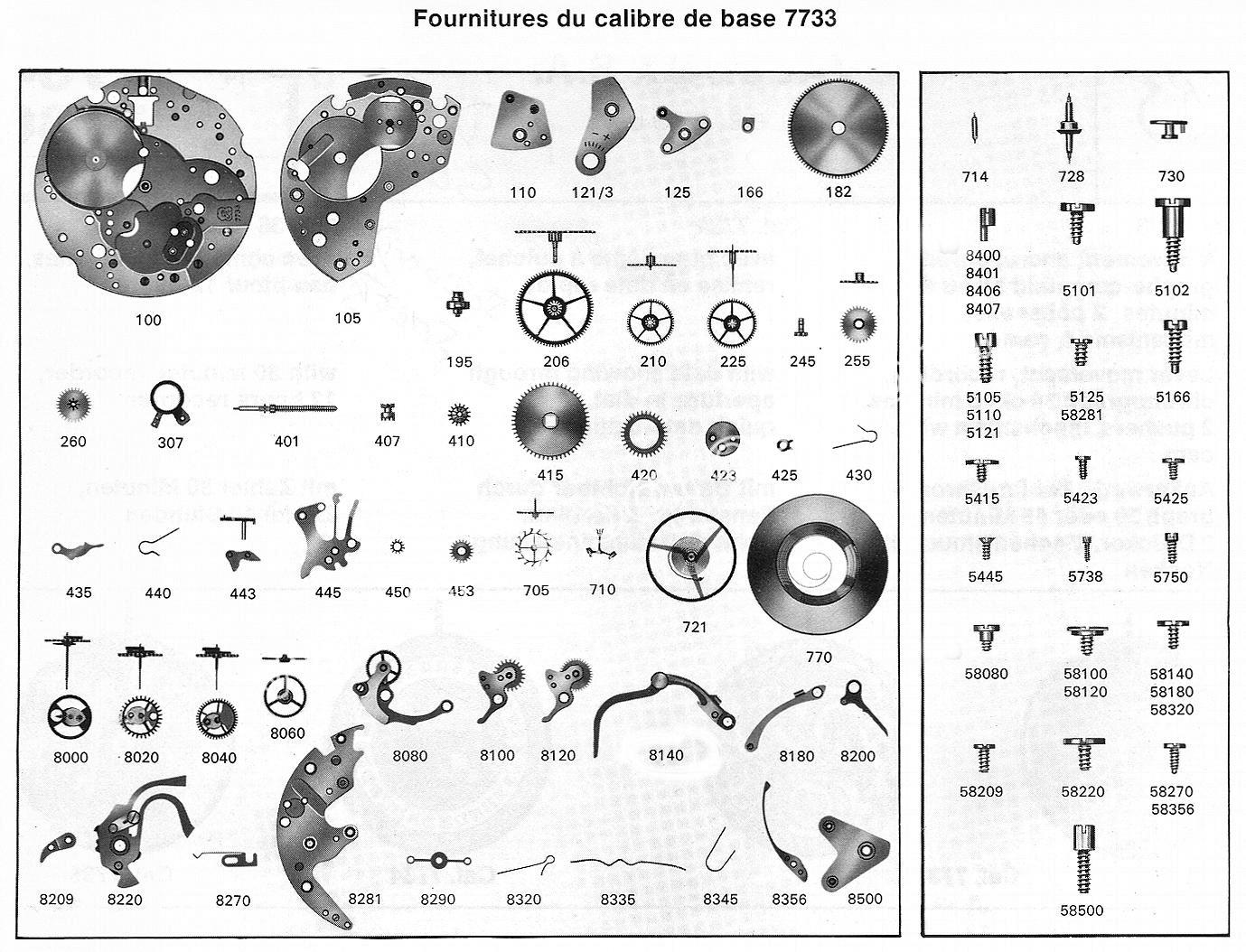

Beloved by brands across a broad spectrum of price segments, the Valjoux 7750 was derived from the manually-wound Valjoux 7733 chronograph calibre, which itself was a descendant of the Venus calibre 188, created by a company established in 1924 and acquired by Ebauches SA in 1928. When Venus terminated independent operations in 1966, Valjoux inherited the Venus cal. 188 from its sister company and produced it is a Valjoux 7730. The manually wound 7730 was redesigned a few years later, making way for the 7733 (the affordable 7733 movement remained in production until 1978, with over 2 million made).

That was in 1969 – a pivotal year in the history of automatic chronographs. Seiko introduced its integrated, column-wheel chronograph with vertical coupling, the calibre 6139. Meanwhile, a consortium comprising Dubois-Dépraz, Büren, Breitling, and Heuer released the Calibre 11, a modular chronograph based on a micro-rotor Büren movement and a Dépraz chronograph mechanism. Zenith, leveraging the expertise of Martel Watch Co. (acquired by Zenith in the late 1950s), developed the high-frequency integrated chronograph 3019 PHC, later famously known as El Primero.

In response, Valjoux, already behind in the innovation game and eager to catch up, hired Edmond Capt, a young watchmaker and engineer who had just begun working at Rolex after completing his studies. Born in Le Brassus in 1946, Capt was 24 years old when he was tasked with creating a new automatic chronograph movement that could be mass-produced and was more cost-effective than the intricate column-wheel calibres 6139 and El Primero, or the modular construction of the Calibre 11. He was supported by Gérald Gander, Donald Rochat, and advanced technology – a gigantic computer at Valjoux’s Neuchatel office – facilitating simulations and functional sequence drawings. This technological edge enabled the 7750 to come out rather fast – and it gained the title of the first watch movement developed using computer-assisted design.

A star is born, meet the Valjoux 7750

The legendary Valjoux 7750 emerged from the manually wound 7733 and incorporated vintage innovations like the oscillating pinion, invented and patented by Edouard Heuer in 1887. It also featured a zero-return mechanism designed by Edmond Capt, based on a 1940s invention patented by the watchmaker Henri Jacot-Guyot, which replaced the traditional column wheel (like the Landeron Cal. 47 and 48). Unlike column wheel systems, the 7750 used levers to operate the chronograph functions via a stamped, oblong-shaped cam. This design made mass production easier and cheaper than its column wheel-operated counterparts. Additionally, cost-saving measures included parts made in Delrin plastic (polyoxymethylene) and simple blocking and jumper springs.

Though the Valjoux 7750 in its original form might not have been as aesthetically pleasing as the El Primero, as design compromises have been made to create a chronograph movement at a reasonable cost, they did not affect the timekeeping – it was highly functional and reliable, which ensured its lasting success in the world of chronographs. As we shall see later, it was modified endlessly by several brands, to become equipped at some point with a column-wheel chronograph mechanism.

Yet, at introduction in 1973/1974, it was characterized by the cam-controlled chronograph function, unidirectional, centre-mounted automatic winding, a straightforward three-plate brass base and not the bridges (calendar plate with modular components, main plate with off-centre centre wheel, hacking lever, and simple bent-spring ratchet, and the top plate with additional winding bridge). Last but not least, the distinguishing feature which conveyed the immediately recognizable look to many of the 7750-powered watches was its design, which provided for the subdials at 6, 9 and 12 o’clock, for the chronograph 12-hour counter, running seconds, and the chronograph 30-minute counter, respectively.

The design, construction and innovation

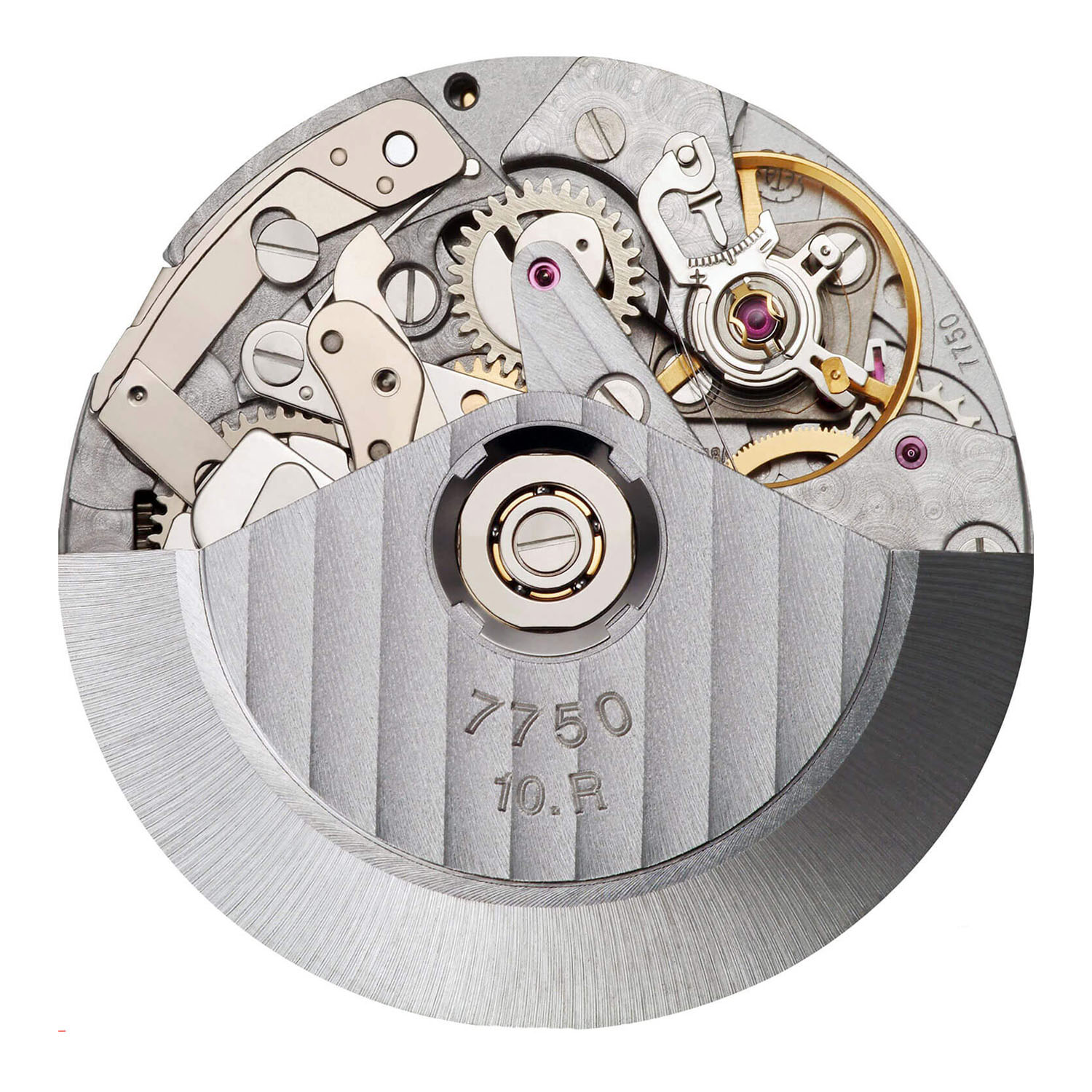

Starting from the top, let’s take a look at the integrated construction of the 30mm diameter, 7.9mm thick, automatic chronograph Valjoux 7750 movement.

The calendar plate of the basic version of the 7750 features semi-instantaneous date and weekday indications, with a quick reset option via the crown. However, using this function between 8 PM and 2 AM is not advisable, as the automatic calendar system is engaged during this time to adjust the wheels to the next day. Using the quick reset during this period could disrupt proper functioning or cause damage.

To access the front side of the mainplate, you need to remove the hands and then the three screws. This reveals the gears that power and set the hands, along with the manual-winding mechanism and the chronograph hour-accumulating wheel driven by the barrel.

The rearward pivot of the counter’s hand turns within a hole drilled into the plate. Given that this pivot rotates only occasionally and slowly, the designers decided against using a jewel at this point. The lever that blocks the elapsed-hours counter by pressing against the teeth of the hour-accumulating wheel was initially made of white plastic. This material choice served the purpose well and exerted less lateral pressure on the pivots of the chronograph hour-accumulating wheel than a metal lever would. Additionally, a slipping clutch on the arbour allowed the lever to engage with the gear in contact with the barrel.

The back of the mainplate showcases the gear train, the barrel with its mainspring providing about 45 hours of power reserve, the escapement, and the balance wheel, which can be hacked to set the time with to-the-second precision. The running seconds hand is placed at the 9 o’clock position, opposite the crown, highlighting the Lépine construction of the 7750.

Initially, the Valjoux 7750 regulated its rate by altering the length of the Nivarox balance spring. In contemporary versions, this method has been replaced by the Etachron system. Additionally, towards the end of the 1990s, plastic parts were replaced with metal ones, and the initial 17 jewels were increased to 25.

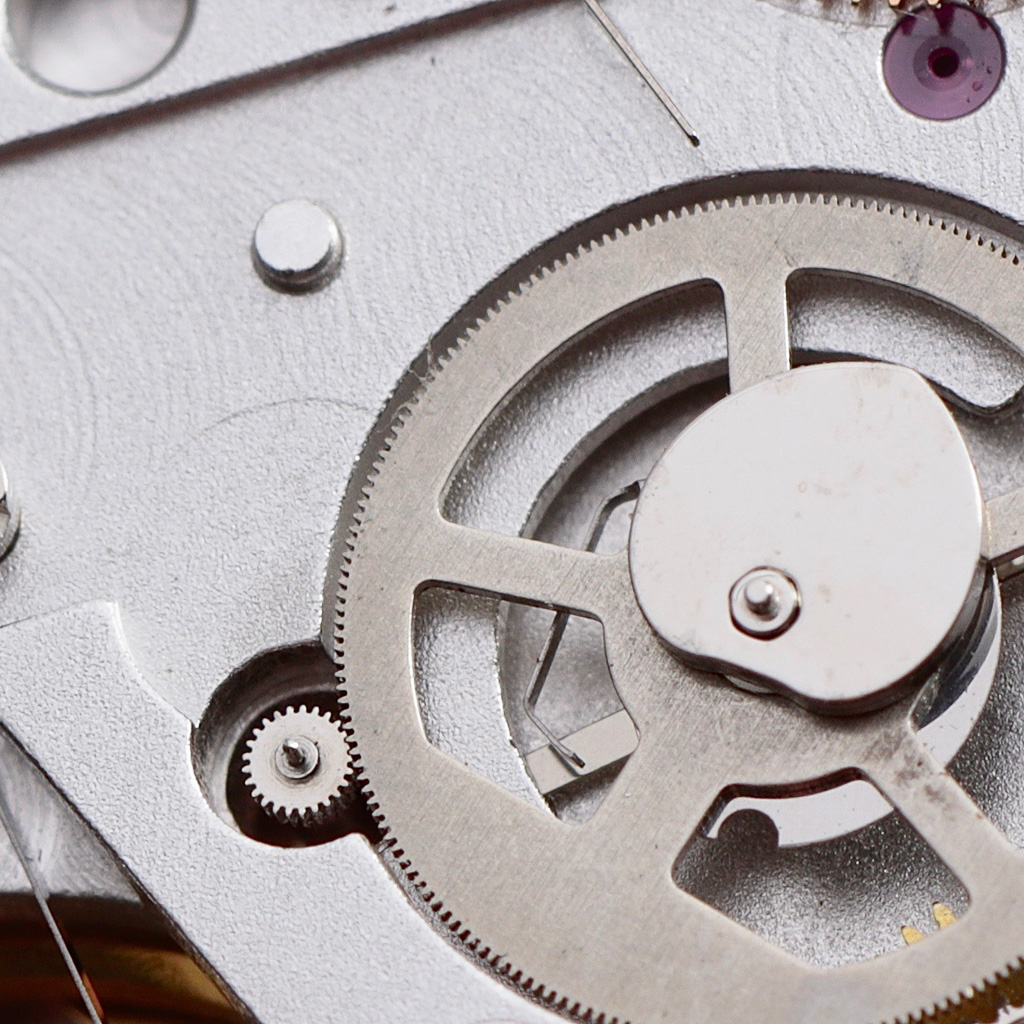

The chronograph’s switching mechanism is located on the back of the movement, becoming visible only after removing the automatic winding assembly. The start-stop-reset functions of the chronograph are controlled by a layered switching cam, which is manufactured through a simple stamping process, similar to many other parts of the 7750 movement. This cam is responsible for making and breaking the connection between the movement and the chronograph. The self-winding mechanism features a ball-mounted rotor that transfers energy to the barrel through a ratchet wheel and a reduction gear, but only during clockwise rotation. While this unidirectional winding does not compromise efficiency, the rotor’s fast rotation in the opposite direction produces a noticeable noise, a characteristic trait of the 7750, along with its 6-9-12 layout.

For those interested in a deeper exploration of the Valjoux 7750, in addition to the available online ETA technical sheets, I highly recommend the deconstruction of the Valjoux 7750-powered Breitling Navitimer by the Naked Watchmaker – it’s an insightful and enjoyable exercise (and was also a perfect source for illustration images, so credits to The Naked Watchmaker).

The rise, fall and insubordination

Reportedly, the Valjoux 7750 achieved an annual production of 100,000 units upon its introduction. However, sales struggled during the quartz invasion, leading to a halt in manufacturing by 1975. The 7750 seemed destined to share the same fate as the doomed El Primero. Senior management was convinced that mechanical watchmaking was ending and ordered the disposal of all machinery, drawings, and tooling for the Valjoux 7750. Edmond Capt, the creator of the 7750, was tasked with this execution.

Much like Charles Vermot at Zenith, Capt defied orders. He discreetly stored as many tools and documentation as he could. In 1978, Edmond Capt went on and joined Frédéric Piguet as Technical Director, later moving to Nouvelle Lémania in 1992 and returning to Frédéric Piguet as General Director in 1994. By 1999, he was appointed General Director for Manufacture Blancpain and Manufacture Breguet, following Swatch Group’s acquisitions and reorganization. Edmond Capt is credited with creating over 30 mechanical and quartz movements. Yet, the 7750 was his first and most celebrated creation, as it played a crucial role in the revival of mechanical watchmaking, securing its place in horological history. Why? It was there and ready for production, thanks to Capt when mechanical watches initiated the comeback sequence and because ETA took over Valjoux in 1985 and gave it a formidable push.

The mechanical Renaissance, resurrection and proliferation

In the early 1980s, the surging demand for mechanical movements underscored the versatility, simplicity, and reliability of the Valjoux 7750. During this period, Valjoux (later ETA) introduced numerous variations of the 7750, many of which remain in production today, such as the 7751, 7753, and 7754.

The 7751, in production since 1986, is a full-calendar chronograph movement featuring a centrally-mounted date hand, day and month displays at 12 o’clock, and a moon phase indicator at 6 o’clock. The 7753 offers a different (3-6-9) subdial layout, with the minute counter at the 3 o’clock position and a date corrector at 10 o’clock. Since 2003, the 7754 has filled the need for chronograph calibres with a GMT function, incorporating an additional 24-hour and date indication. These movements continue to be part of ETA’s contemporary Mecaline catalogue.

In addition to these enduring models, the early 1980s saw the introduction of several other 7750-based movements to satisfy the growing demand for chronographs, contributing significantly to the mechanical watch resurgence. These included the 7757 with a regatta countdown indication and the 7758 with a moon phase complication. A range of manually wound chronograph calibres was also launched, such as the 7760, the 7761 (without the chronograph hours counter and day indication), the 7768 (similar to the 7761 but with an added moon phase indication), and the 7765 (featuring a 30-minute counter at 12 o’clock and a date indication, but without the chronograph hours and day indication).

The Valjoux 7750, the foundation of watch brands’ success

Before these 7750 derivatives were phased out in the late 1990s and early 2000s, they powered numerous watches and the 7750, in its original form and various adaptations, has been a staple in the watchmaking world for 50 years. This widespread presence and enduring success are a testament to its genuine quality and performance. The Valjoux 7750 and its variants have powered watches released by IWC, Montblanc, Breitling, Chronoswiss, Heuer, Omega, Porsche Design, Sinn, Fortis, Tudor, Eberhard, Alpina, Bremont, Franck Muller, Panerai, Chopard, Ikepod, Bell & Ross, Maurice Lacroix, Louis Erard – and just about every other brand name you can think of that survived the quartz crisis or was created after and came looking to reclaim the market share.

When Breitling celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1984 with the release of the Chronomat, it introduced a completely new design language that would significantly contribute to the brand’s success. This important model was powered by the Valjoux 7750, which also powered the iconic Breitling Navitimer. Thus, two of Breitling’s most important chronographs owe their success to Edmond Capt and his remarkable creation.

Kurt Klaus, the legendary watchmaker known for developing IWC’s famous perpetual calendar module, used the Valjoux 7750 as a base to create the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Chronograph (calibre 79261), which debuted in 1985. Another renowned figure, Richard Habring, designed a 7750-base split-seconds chronograph movement with an additional pusher at 10 o’clock for the IWC Doppelchronograph, introduced in 1992. In 1993, IWC celebrated its 125th anniversary with the complex, 7750-base Il Destriero Scafusia, featuring a perpetual calendar with a four-digit year display, split-seconds chronograph, flying tourbillon, and minute repeater.

The 7750 also served as the foundation for several other notable IWC calibres, including the 79251 (a self-winding rattrapante chronograph with a perpetual calendar and moon phase indicator), the 76061 (a hand-wound movement with a chronograph, perpetual calendar, and tourbillon), and the 79091 (a Valjoux 7750 with an in-house IWC perpetual calendar module and minute-repetition mechanism). The list goes on, highlighting IWC Schaffhausen’s deep appreciation for the robust and reliable 7750.

Among the notable movements based on the 7750 is the world’s first mechanical chronograph movement with a built-in alarm, the F-2001 developed by Fortis in collaboration with Zurich-based independent watchmaker Paul Gerber. Introduced in 1997, this movement powered the Fortis B-42 Cosmonaut Chronograph Alarm. Another example is the Eterna 6036, a complex 800-part movement launched in 2004 within the Porsche Design Indicator P’6910. This calibre featured a jumping display of chronograph hours and minutes at 3 o’clock, combined with a power reserve indicator and running seconds.

When TAG Heuer relaunched its Carrera series in 2005, it featured the TAG Heuer Calibre 16, which, as you might have guessed, was based on the 7750 – which powered earlier Heuer chronograph models like the 1977 Kentucky and Pasadena, showcasing the enduring legacy and versatility of the 7750 movement.

As you can see, it took a little while for watchmakers to fall in love with the 7750. This movement quickly proved to be a reliable, durable, and affordable workhorse. Beyond its cost-effectiveness, it was easy to service and adapt to the specific needs of various brands. It was solidly built with a thickness of 7.9mm, which added to its appeal.

To explore its potential flaws, I spent an entire day reading through dedicated forum messages, searching for any systematic errors or frequently occurring issues. I found that most “users” praised the 7750, and most problems stemmed from improper handling rather than inherent flaws. Admittedly, the coulisse lever mechanism doesn’t offer the same tactile satisfaction as a column-wheel chronograph when operated, and the rotor can be noisy, with the famous wobble produced when the rotor spins counterclockwise (not winding). Also, it needs a top-tier finish to make the 7750 attractive (at least in comparison to more refined movements).

The curious upgrades

Interestingly, what initially defined the image of the 7750 – the cam-and-lever mechanism and its utilitarian appearance – later inspired numerous watchmakers. Brands focused on enhancing the 7750, adorning it with exquisite decorations. For instance, the Chronoswiss Opus Cal. 741, by Alfred Rochat & Fils SA, features intricate skeletonization, showcasing the transformation of the 7750 into a symbol of functionality and craftsmanship. See below a modern version of the Chronoswiss Opus, still powered by an openworked 7750.

Furthermore, some sought to enhance the 7750 by equipping it with a column-wheel system, elevating its appeal, functionality and aesthetics. Examples of this evolution include the Chronoswiss rattrapante chronograph Cal. 732 by Alfred Rochat, Panerai OP XVIII, late versions of Hublot HUB44, Graham G 1742, Vulcain V-50, all enhanced by La Joux-Perret. Additionally, the IWC 69000 series and Longines 688 followed suit, embracing the column-wheel system as an improvement.

In 1999, with the advent of the Co-Axial escapement, Omega, which relied on Frédéric Piguet and Lemania for chronograph movements, sought to build a chronograph calibre to accommodate the Co-Axial technology and naturally turned to Swatch Group’s ETA for help, which in a few years delivered what we know as Omega cal. 3330, a COSC-certified chronometer with a column-wheel mechanism, Co-Axial escapement and a silicon balance spring – based on the Longines L688, which in turn is based on ETA Valgranges A08.L01 and the Valgranges calibre family is based on the Valjoux 7750.

Regarding the Swatch Group and ETA 7750 Valjoux, there’s a continuous effort to refine this renowned chronograph movement and customize it to meet the specific needs of the group’s brands. In the 2000s, ETA undertook the task of creating specialized versions of the 7750 tailored for companies within the Swatch Group. This initiative led to the development of the larger Valgranges A07 line and the ETA A05 line, specifically designed for brands like Tissot and Rado. One exciting example is the A05.231, which incorporates modern technology and is featured in the Tissot Telemeter 1938 – I highly recommend taking a closer look at this fascinating development, which was once the topic of our article.

Only recently, we introduced a new watch from Union Glashütte. This Swatch Group brand updates its movements to feature nice decoration and silicon technology – a notable example is the UNG-25.S1, instantly recognizable as a 7751. Hamilton’s chronograph calibre H-21, introduced in 2011, is a modified version of the 7750, yet with the refined kinematic chain, and improved mainspring (60-hour power reserve).

The copycats

It’s no surprise that Swatch Group brands widely use the ETA 7750 Valjoux and its derivatives. The group’s strategy of prioritizing its needs before supplying external customers led to a significant shift in the industry. In 2002, Swatch Group announced that ETA would cease delivering ébauches to external clients, focusing instead on its brands. This move forced many watchmakers to seek alternative suppliers or invest in developing in-house calibres, including chronographs – a challenging and costly endeavour.

This shift created opportunities for companies like Sellita. Until 2003, Sellita was entrusted by ETA with movement assembly. In response to the reduced deliveries of the ETA Valjoux 7750, Sellita developed its alternative, the SW500, a so-called clone movement, which has been in production since 2009. Watchmakers quickly embraced the SW500; early adopters from the lower-priced segment, such as Invicta and Glycine, were followed by brands like Sinn, Breitling, Tudor, Tag Heuer (Calibre 16) and IWC (cal. 75320). Initially offering only a basic ETA 7750 clone, Sellita gradually built up an extensive list of SW500-series chronograph movements, including manually-wound and mono-pusher variants, and made some improvements. Today, the SW500 is utilized by numerous brands, which are too many to list comprehensively.

Although much later, La Joux-Perret joined in and offered its L100, an automatic integrated chronograph calibre, built on the 7750 architecture, yet with a column wheel instead of a cam-and-lever system to compete with the Sellita SW500 series. Also, there’s a Chinese alternative to ETA Valjoux 7750, the 3L series movement, often called the Asian 7750, produced by the Shanghai Watch Factory, owner, among others, of the Sea Gull brand. If this is not proof of 7750 being pervasively present, what is?

Concluding thoughts

To conclude this short essay on one of the most widely-used chronograph movements in watchmaking history, it’s important to remember that the Valjoux 7750 introduced innovative solutions that reduced production costs while enhancing reliability. Designed as a utility movement, it was intended for rapid, large-scale production, making good-quality chronograph calibres accessible to a broader customer base, not just the few.

Ultimately, the 7750 enabled brands to offer chronograph watches to a wider customer base, sparking interest and appreciation for mechanical movements, so it played an important role in securing the future of the watchmaking industry, ensuring that the tradition of mechanical horology would continue to thrive.

9 responses

Thank you for writing this article. Content like this is all too seldom seen in watch publications nowadays. Well done indeed.

While I appreciate the 7750 for its democratisation of mechanical chronographs, I sometimes wish they would throw that movement in the bin and design something thinner or smaller.

If you take watches based on the hand wound versions of it, you still end up with a whopping 13-13.5mm thickness, and I would love, love for folks to return to the smaller chronographs that folks produced around 1940-1950.

How cool would it be if someone, somewhere would design an affordable chronograph that, complete with automatic rotor, would result in a watch that’s 13mm thick, or even less?

So having the 7750 around is a blessing and a curse at the same time. The fact that it’s bomb proof removes the impetus to design something more elegant.

Fantastic article.

I’ve always had a soft spot for 7750, especially as you can find it in such a huge range of watches from different brands, with numerous interesting variations and modifications.

Dear Denis, thank you for putting the results of your deeply researches in this fantastic article. @monochrome watches: this article show me again your deep knowledge, and you share always the latest news.

@Robert Vallender – thank you so much for these kind words. Much, much appreciated!

ciao Denis, thank you for this comprehensive article.

Even if the story of 7750 is generally known, there’s always something to learn. It would be great to have a similar article on the Lemania 5100 which as far as I know for some time has been a competitor of the 7750 (at least in terms of robustness, easy of built and “blasphemous” use of plastic parts).

Thanks again,

best regards,

Andrea

There is a very interesting presentation by Richard Habring, hosted by the Horological Society of New York, from October 2019. In the presentation, Mr. Habring discusses how his (very) small watch company in Austria was able to create a movement based on the 7750 gear train (with which Mr. Habring was very familiar, having created a cam lever split-second module for IWC’s chronograph, based on the 7750 movement). Habring2 was able to source parts manufactured by a group of small (many family owned) businesses throughout Austria, Germany and Switzerland. It is a worthy chapter in the story of the 7750, and the video presentation (in its entirety) can be found on the YouTube platform.

Thank you for taking the time to share your expertise on this movement!

Dear, LIV claims to use these movements, however, their watch (compared ot others) seem priced very low, .. could they be copies?

Buongiorno quale Gander Monta Il 7750 Grazie