The Rise of Mechanical Watches Among Quartz-Focused Brands

Mechanical watches are having a second renaissance of sorts among unlikely brands as shifting consumer preferences demand change.

The Quartz Crisis of the 1970s and 1980s was a defining moment for the industry, to say the least. Following Seiko’s Astron in 1969, the first quartz watch to hit the market, a huge swathe of traditional brands closed down as cheap, extremely accurate and virtually maintenance-free Japanese quartz watches hit the streets. Add to this the appreciation of the Swiss Franc, which made exports even more expensive, and Japan was suddenly in a league of its own. Approximately two-thirds of Swiss watchmakers disappeared, and within a decade, Swiss exports declined by more than 50%. During this period, many brands shifted to quartz (at least in part) to survive, although others thrived and created an identity around the new technology. Swatch even formed as an effective answer to Japan in 1983, bringing inexpensive yet stylish plastic quartz watches to the masses – and subsequently jumpstarting the Swiss industry overall.

Times have certainly changed as mechanical watches have been back in fashion for a couple of decades, but the comeback started in earnest in the 1990s. Quartz watches, for the most part, are viewed as cheaper alternatives today, with exceptions for specific, purpose-built models like Casio’s G-SHOCK or Citizen’s Eco-Drive models. That said, many luxury brands continue to offer high-end quartz models, such as Cartier, TAG Heuer, and Omega, indicating that mechanical and quartz movements still have a place at all levels. Most surprising, however, is the recent trend of quartz-focused brands – ones that adapted and thrived during the Quartz Crisis and beyond – embracing mechanical watches after decades of dormancy or even for the first time. Watchmakers like Timex, Casio and others are responding to changes in consumer preferences for mechanical timepieces.

Timex

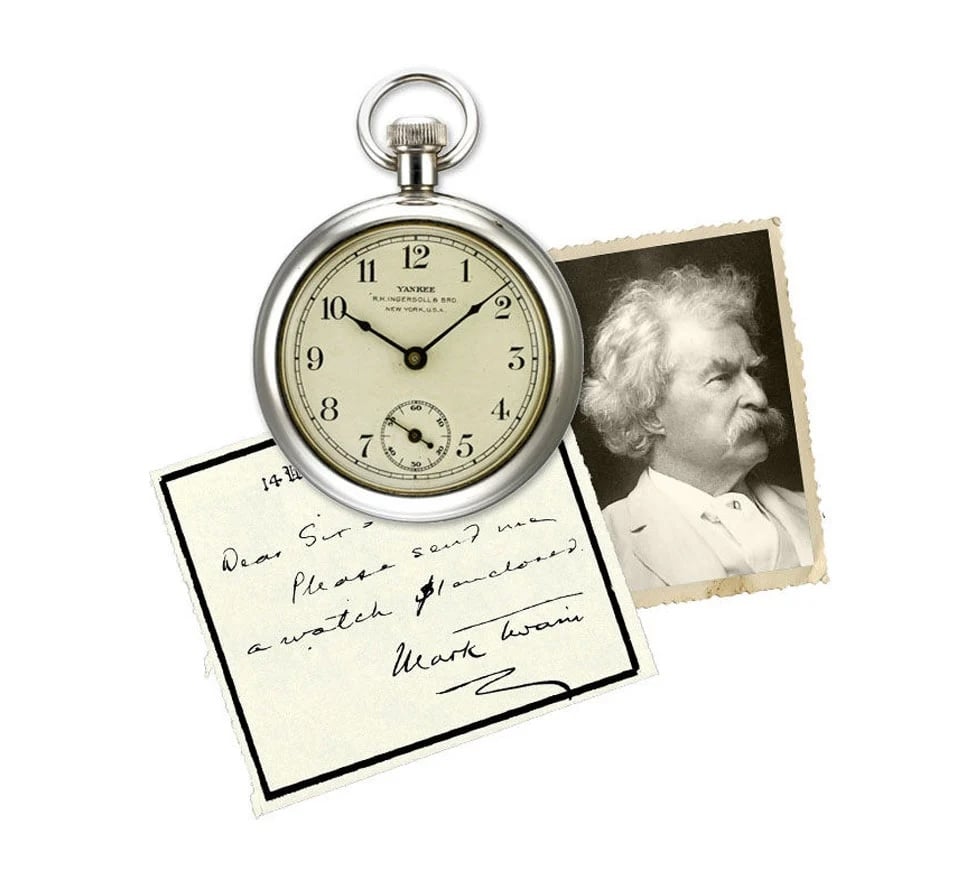

Timex is among the most recognised and successful watchmakers in history (with some hardships along the way), founded in 1854 in Connecticut as the Waterbury Clock Company. Of course, everything was mechanical back then, but the brand focused on affordability for much of its existence. As the name suggests, clocks were the initial focus and the company was among the largest for American sales and exports to Europe. By 1887, a new non-jewelled pocket watch was designed with only 58 parts, comprised mostly of inexpensive and easy-to-produce punched sheet brass. Production hit 200 pieces per day the following year, and the Waterbury Watch Company was formed in 1880 to continue mass production of affordable watches. Within a decade, the watchmaker had become the world’s largest by volume. In 1922, the Waterbury Clock Company purchased Ingersoll after it went bankrupt the prior year, but the Great Depression caused fragmentation and selloffs that threatened the company’s solvency. Believe it or not, it was Mickey Mouse that saved the watchmaker after a licensing agreement was reached with Walt Disney in 1930. The now iconic Mickey Mouse watch debuted in 1933 at the Chicago World’s Fair and became the brand’s first million-dollar series. It remains a popular image on watch dials today and even an animated option on smartwatches.

During World War II, the company produced military fuse timers and received the Army-Navy “E” Award in 1943, and shareholders soon renamed the brand the United States Time Corporation. Following the war, affordable wristwatches became the renewed focus and wartime techniques like automation and the use of Armalloy came into play. Armalloy was a super-hard alloy that was adapted for movement bearings to replace more expensive jewels, and the success of the new production methods and materials led to another name change in 1950: Timex. “Time” was combined with “X” as the latter represented innovation and technical expertise. In 1956, torture tests were televised live to demonstrate durability, including freezing watches, putting them in water tanks with a running outboard boat propeller and shooting them with arrows. Famed news anchor John Cameron Swayze hosted many events and said after successful tests, “It takes a licking and keeps on ticking”. He didn’t create the line himself, but it became one of the most successful marketing slogans in history.

Fast forward to the Quartz Crisis, and Timex recognised the opportunity to shift from mechanical to quartz analogue and digital watches, with the latter being a huge trend at the time. Digital watches were not only easy to read, extremely accurate and a complement to the rising personal computer/tech era, they also provided a smorgasbord of complications that were rare and very expensive on mechanical counterparts (if available at all) – alarms, perpetual calendars, chronographs, multiple time zones, calculators, memory storage and even games. By 1982, Timex ceased production of all mechanical watches and fully embraced quartz, and the brand became synonymous with inexpensive, reliable and durable watches for the masses – the “Everyman” watch. Timex dominated sales in the 1980s and 1990s with quartz watches, particularly in the United States, alongside Japanese leaders such as Casio, Seiko, and Citizen.

Timex Ironman and Indiglo

In 1986, the Timex Ironman Triathlon debuted with an aggressive, durable design featuring a large LCD screen and functions for endurance athletes like an 8-lap memory and 100 metres of water-resistance. It became the best-selling watch in the United States within the first year and remains one of the brand’s most popular collections. Designed by John T. Houlihan, the Ironman had large, front-mounted buttons that allowed for easy lap timing, which was a specific request from runners. In 1992, Timex introduced Indiglo, which provided a bright and perfectly even backlight on both analogue dials and digital displays at the push of a button, putting all conventional lume to shame. It used a patented electroluminescent panel with a bluish-green glow and remains unsurpassed today. The iconic Ironman was among the first to debut with Indiglo, and around 70% of all Timex models had the lighting system by the late 1990s. As Timex moved into the 2000s and beyond, it maintained massive global success with affordable quartz and Indiglo technology, having little reason to move away from the battery. The brand is known for adaptability, however, and made a surprising shift to keep up with evolving consumer preferences.

Timex Marlin

In 2017, 35 years after successfully abandoning mechanical watches for quartz, Timex returned with the hand-wound Marlin – a reissue of a 1960s model with a 34mm case and reliable mechanical movement (sourced from Seagull). Reviving watches from the past has been a big industry trend and Timex had also brought back quartz models like the classic Ironman and Q Timex, but pulling from its older mechanical portfolio was a big hit. The price was only USD 199, so affordability was maintained, and the collection soon expanded to multiple sizes, including 38mm and 40mm, with automatic Miyota movements and exhibition casebacks. More mechanical collections followed like Deepwater, MK1 and Expedition, and the continued growth is a real sea change for a brand so closely identified with quartz.

Timex Atelier

It doesn’t end here as Timex recently released the Atelier collection, labelled as “The Next Chapter” by Chief Creative Director Giorgio Galli. The brand is dipping its toes in the accessible luxury market with prices north of USD 1,000, but it demonstrates a commitment and recognition of how important the affordable luxury segment has become. The stainless steel Atelier GMT24 M1a has a Swiss Landeron GMT automatic, sapphire crystal, Super-LumiNova, exhibition caseback and 100m water-resistance. Finishing is a step above the norm, and the price is reasonable at USD 1,450. The Giorgio Galli S2Ti is an even higher-end piece with a titanium case and Sellita SW200 decorated with perlage and Côtes de Genève, and a black ion-plated rotor. It follows the Giorgio Galli S1 from a few years ago and the price is a bit higher at USD 1,950, but still reasonable for what’s being offered. Both the Atelier and Giorgio Galli S2Ti feature innovative, tool-free I-Size adjustable bracelets (to remove or replace links) and quick-release levers, and can certainly rival some mechanical pieces from Longines and Hamilton. I never thought I’d say that about a Timex. How times have changed.

Casio

Casio was founded in 1946 by Tadao Kashio in Tokyo, but not as a watch company. Its first product of note was actually the yubiwa pipe – a ring that held a cigarette for hands-free use and the ability to smoke it down to the nub. The brand soon shifted to electric analogue calculators (without digital screens) in the early 1950s and launched the first all-electric desk calculator, the 14-A, in 1957. This used 341 relays and consisted of a typewriter-sized unit mounted on a rolling desk-sized cabinet that housed the necessary components. At the equivalent of USD 15,000 today, it was pricey yet revolutionary for businesses. In 1965, the more advanced 001 electronic desktop calculator was a true desktop unit without the need for a supplementary rolling cabinet. The display had 10 analogue numbers via rolling digits (like a vintage cash register), although that soon shifted to a LED digital display. In 1972, the Casio Mini became the first personal and truly portable calculator, and the following LC-78 Casio Mini Card shrunk down to a card-sized unit and was only 3.9mm thick. Casio was now firmly established as a world-class calculator brand and technology company, and offices and manufacturing facilities spread globally with a presence in the United States, Germany, London and more.

Casiotron QW02 and Quick Progression

In 1974, Casio leveraged its experience with calculators and released its first digital watch, the Casiotron QW02. At the time, it was the only digital quartz watch with an automatic calendar that adjusted itself for longer and shorter months. February still needed a manual adjustment, so it was an electric annual calendar, but that was soon updated to be a true perpetual calendar. In 1976, the X-1 added both a world time complication and a stopwatch, and Casio became a leader in the quartz digital watch space alongside Seiko and soon, Timex. Another game changer debuted in 1977: the F100, featuring the first all-resin case and strap, bringing a very lightweight, durable, and corrosion-resistant material to the wrist. Resin also simplified manufacturing as it’s easy to work with, lowering prices as it established quicker mass production techniques.

Of course, the brand had to merge its calculator and watch portfolio, although it wasn’t the first to do so. Pulsar released the first calculator watch in 1975 with an LED screen, but Casio went on to produce the most varied LCD calculator models that included data banks and scientific functions. It released its first calculator watch in 1980, the C-80, which used a resin case and was marketed as an inexpensive “microcomputer on your wrist”. In 1984, one of the most iconic calculator watches of all time debuted, the no-nonsense CA-50 that appeared on the wrist of Marty McFly in Back to the Future. As mentioned in our previous ABCs article about iconic watches appearing in movies, the right movie placement can elevate watches to legendary status, and that’s certainly the case with Casio’s CA-50 and its successor, the 1988 CA-53W, which appeared in the two BTTF sequels and on the arm of Walter White in Breaking Bad. The CA-53W is still in production almost 40 years later as model CA-53W-1.

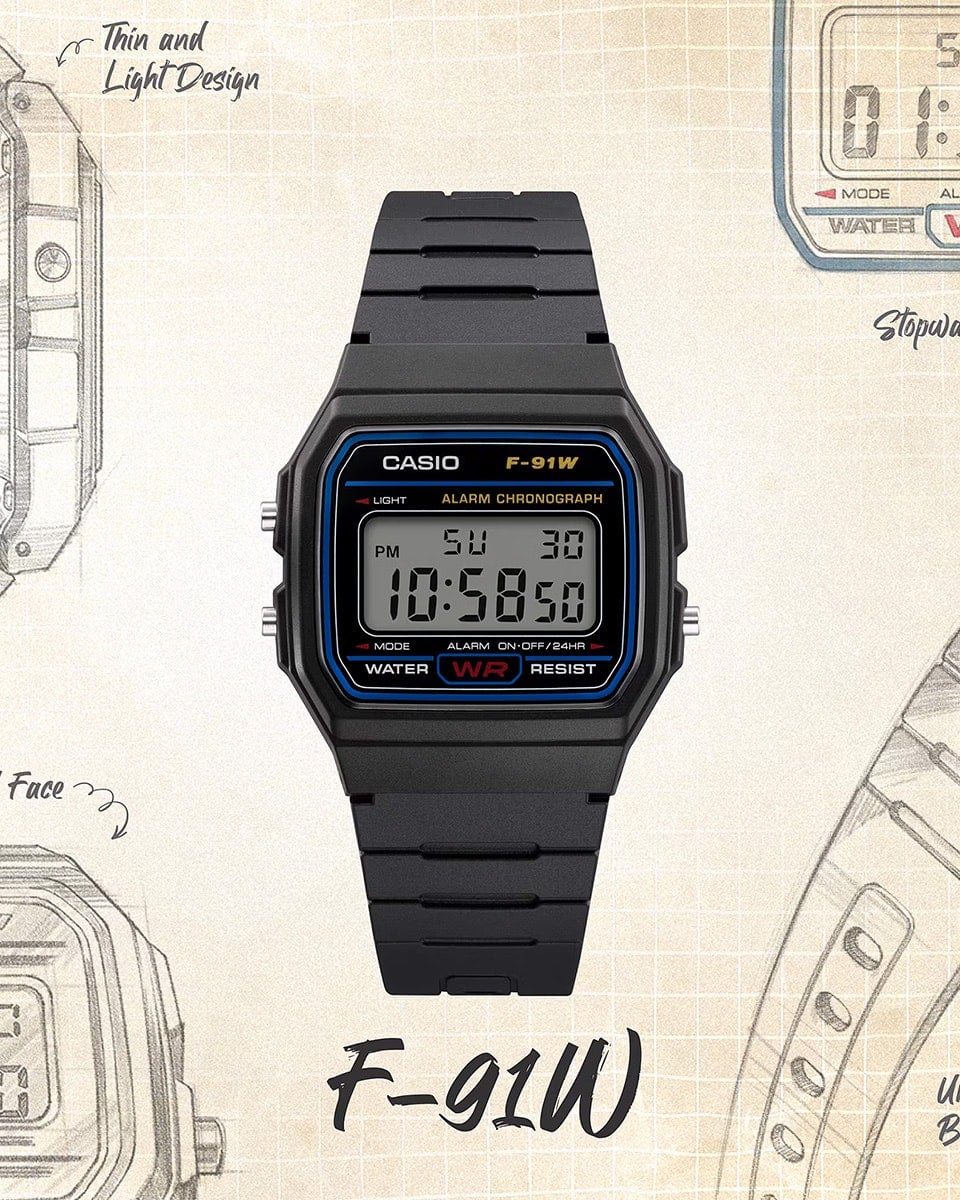

Casio F-91W and G-SHOCK

Along with the aforementioned calculator watches, these are Casio’s most iconic. The F-91W was launched in 1989 as a simple, durable resin digital watch that was lightweight, easy to wear, looked good, and just got the job done. Best of all, it was among the most affordable digital watches and remains in production today as the F-91W-1. The model is also recognised as the highest production digital watch of any brand, with over three million units produced per year (well over 100 million since 1989). It has everything you need from a watch – exceptional accuracy, alarm, perpetual calendar (except for leap years), chronograph, water resistance and an LED screen light. Worn by celebrities, presidents, and even British Army soldiers in the field, these can be purchased today for approximately EUR 20, brand new.

The G-SHOCK needs no introduction, as it has established what it means to be a tough-as-nails, go-anywhere watch. Launched in 1983 as model DW-5000C, the resin case had a hollow construction that supported the digital module at various points with a shock-resistant “floating” design, while a reinforced urethane bezel protected the crystal and side buttons. Five durable layers protected the watch from impacts and water-resistance was 200 metres from the start. The G-SHOCK immediately became popular among firefighters and skateboarders, who appreciated its ability to withstand hard impacts and other severe conditions. By the 1990s, it was a major fashion statement for kids and young adults, while models like the MRG-100 with full-metal cases were released for more discriminating watch enthusiasts. The successor to the original was the DW-5600 in 1987 which remains in production today for less than USD 100. The G-SHOCK portfolio is now vast with both analogue and digital models, but all represent a standard of toughness that few watches can match at any price.

Casio Edifice EFK-100 Automatic

With all the success Casio has enjoyed with quartz watches, particularly its iconic digital models, but also analogue, it was a big surprise to see an automatic series launch in 2025. It’s the first mechanical watch for the tech-focused brand that also makes Casiotone electronic music keyboards and Privia digital pianos, digital cameras, calculators, cash registers and more. They hit a triple with the Edifice EFK-100 Automatic as it’s great looking, well designed and very affordable, giving Japanese rivals Seiko, Citizen and Orient a run for their money. It expands the Edifice collection of metal quartz watches and pulls (almost) no punches – integrated design, multiple textured dials with a forged carbon option, date, sapphire crystal, exhibition case back, 100m water-resistance and a forged carbon case option. I say triple, not a home run, as it uses a pedestrian Seiko NH35A automatic, so a bit low on the totem pole and not in-house (yet). That said, it’s also a reliable and serviceable workhorse with a beat rate of 21,600vph (3Hz) and a 40-hour power reserve. With a starting price of EUR 279/USD 280, it’s not the cheapest Japanese mechanical watch available, but it offers enough to justify the still very accessible price. The forged carbon model is EUR 449, but that’s less than half the price of the forged carbon Tissot PRX at EUR 1,075. This is a great first effort for a mechanical line with very slick styling, the use of forged carbon and a safe, familiar movement from its home country to get things started and kind of test the waters. Well done, Casio!

Swatch

Unlike Timex and Casio, Swatch didn’t have a period of decades before introducing (or reintroducing) a mechanical watch, so this story is a bit different. Swatch was trying to jump-start the Swiss mechanical watch market, which was at a low point in the early 1990s following the Quartz Crisis. It wasn’t following a trend like Timex and Casio, but trying to create one. Swatch was already the quartz brand for the cool kids by 1990 and in a perfect position to introduce mechanical watches to this newer generation, while also going after intrigued traditionalists. So, this will explain how a brand founded on quartz used its massive success to reinvigorate a floundering mechanical market, because the Swiss have each other’s backs.

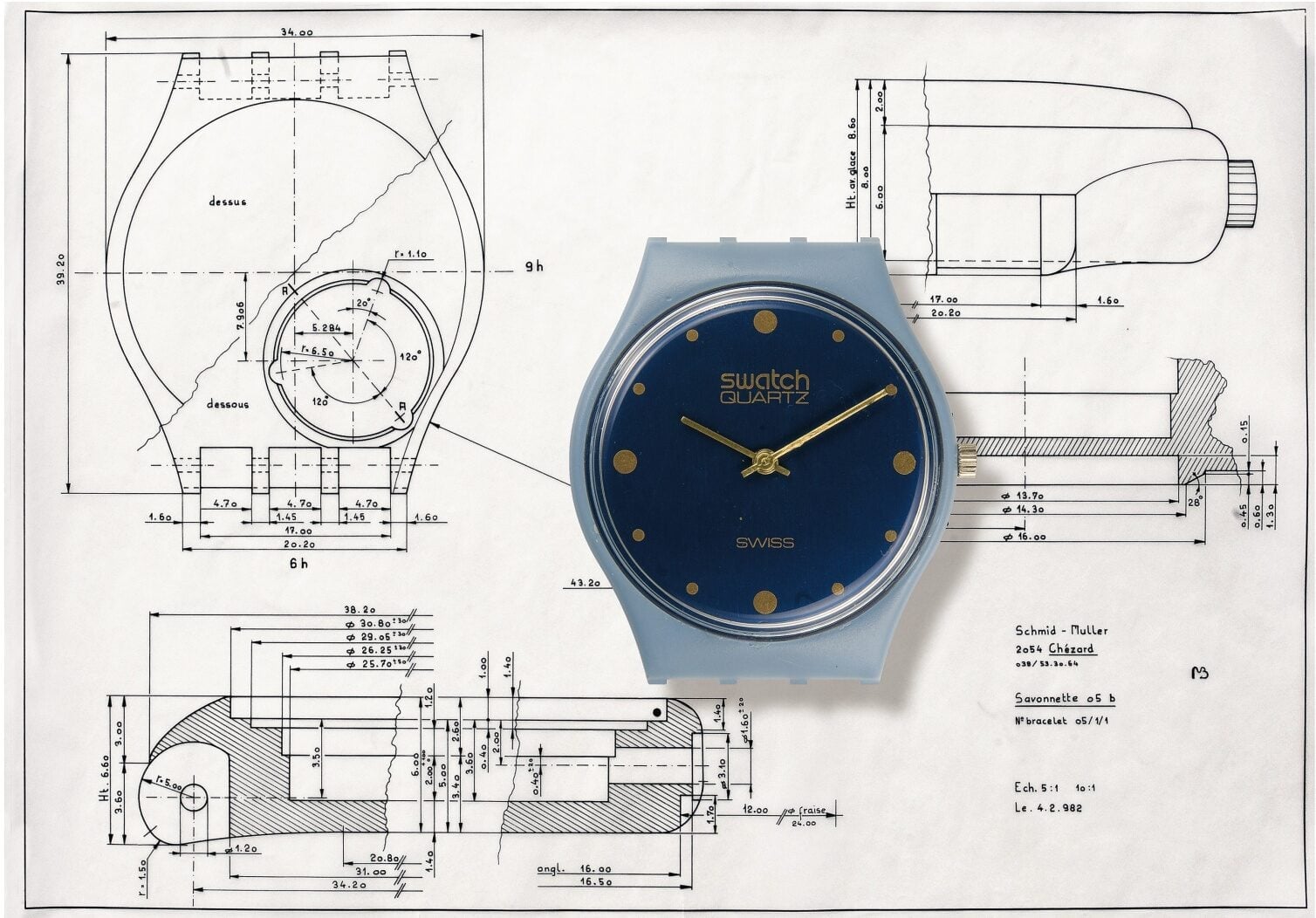

Swatch was founded specifically to counter the exploding Japanese quartz market that was eating Switzerland’s lunch. Inexpensive plastic analogue quartz watches with fun and youthful designs made Swatch an overnight success and a sudden Japanese contender. The brand was launched in 1983 with entrepreneur Nicolas Hayek and ETA’s CEO Ernst Thomke (among others), and twelve whimsical 34mm models debuted to massive enthusiasm (including a 13th special edition Jelly Fish model (GK100) with a transparent case/strap and quartz movement on full display). The Swatch name is a play on “Second Watch” – as in an inexpensive second watch to own – and the idea was a gamble at a time when inexpensive digital counterparts with a high-tech vibe and multiple complications were all the rage. A kid could pick up a Casio with allowance or lawn-mowing money that had an alarm, stopwatch and calendar, and was also easier to read than an analogue dial. However, there was nothing quite like a Swatch – affordable Swiss-made analogue quartz watches that evoked emotion with colours and funky aesthetics. Production was simplified with one-piece plastic cases (where the back acted as the movement mainplate), a reduction of total parts to 51 (from an average of over 90) and a focus on automated assembly to keep prices low, which were CHF 39 to CHF 49. Within two years, over 10 million Swatch watches rolled out of the factory, and the generated profits were used (in part) to restructure and again save the Swiss watch industry.

What happened next persists today: Swiss brands were consolidated under a single parent company when ASUAG (Allgemeine Gesellschaft der Schweizerischen Uhrenindustrie) and SSIH (Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère), both financially struggling Swiss conglomerates, merged in 1983. The company became a private entity in 1985 under Nicolas Hayek, who was now CEO of Swatch, and was renamed SMH (Société de Microélectronique et d’Horlogerie) in 1986. The name changed a final time in 1998 to The Swatch Group, which is now the largest watch conglomerate in the world with 16 major brands including Omega, Breguet, Blancpain, Longines, Hamilton and Tissot. The group also owns ETA, which is the largest Swiss movement manufacturer and supplier to many of its partner brands. With the lightning strike that was Swatch and key management to bring together Swiss brands under one umbrella (as there’s strength in numbers), the industry was basically saved by inexpensive plastic quartz watches coupled with brilliant, out-of-the-box marketing strategies. Of course, there were investors and bankers along the way, but without the early success of Swatch, it’s possible that it wouldn’t have materialised.

Mechanical Swatch

The Irony collection, launched in 1996, introduced stainless steel cases to Swatch for the first time. This was a big evolution where higher-end, more expensive models were introduced to entice both current fans and a new demographic, but there was a bigger strategy behind it. A year later, the first Irony models were fitted with ETA 2842 automatics, so the plastic fantastic quartz brand was now releasing steel mechanical Swiss watches with the signature design language that made them so popular. These also remained affordable, so proper Swiss mechanical watches were available to the masses through Swatch, bringing sophistication to younger fans and intrigue to a more mature audience. Plastic quartz collections still dominated, of course, but the brand was helping to reinforce the allure of Swiss mechanical watches to the post-Quartz Crisis crowd. It was a successful first step, but the broader strategy was to introduce in-house mechanical watches (via partner ETA) in a very Swatch-like way, both in style and production. This would create a more prominent and visible mechanical presence within the portfolio. Enter Sistem51.

Swatch Sistem51

At Baselworld 2013, Swatch introduced the “world’s first mechanical movement (calibre C10111) with entirely automated assembly.” Sistem51 followed the same successful formula that started the brand in 1983 – plastic case, a significant reduction in parts and automated production – everything was assembled by machines without human intervention in clean-room environments. The unique automatic movement was 100% Swiss-made with only 51 parts, mirroring the 1983 quartz original, but now compared to 130 or more mechanical parts. Everything was anchored by a single central screw with a transparent rotor for a full view of the movement. The power reserve was impressive at 90 hours and the movement was made from an anti-magnetic alloy of zinc, copper and nickel called ARCAP. Regulation was factory set via laser and the escapement couldn’t be adjusted, but accuracy was rated at +/-10 seconds per day. In Swatch tradition, the movement was permanently sealed within the case, keeping it firmly protected but without the ability to be serviced. It was very affordable at CHF 130/USD 150, maintenance-free and ultimately disposable – a “second watch” to enjoy for years and then replace. However, Swatch watches were often a primary watch for younger fans, going back to 1983, and the Sistem51 was no exception. Sistem51 movements eventually merged with the Irony collection, offering this revolutionary, simplified design in more premium stainless steel cases for more seasoned enthusiasts.

Citizen

This is an interesting one, as Citizen never fully ceased mechanical production, not to mention its massive movement manufacturing division, Miyota. That said, Citizen devoted a vast amount of capital and focus to quartz technology for decades with major milestones under its belt. Like Timex and Casio, Citizen was (and remains) a department store favourite with a wide variety of inexpensive quartz models shining through glass cases. Although there are a lot of parallels here with Seiko, that Japanese watchmaker has always maintained a stronger mechanical portfolio. Citizen was founded in Tokyo as Shokosha Watch Research Institute in 1918 by Kamekichi Yamazaki, although the Citizen brand name started in 1930 following a takeover by Japanese and Swiss investors. Between this, the first pocket watch was released in 1924 with Citizen on the dial (as a watch for all citizens). Citizen went on to become one of the most innovative and technologically advanced watchmakers in the world, with many industry firsts, pushing quartz potential to the max.

Class Leading Innovations

In 1956, Citizen launched the first shock-resistant watch in Japan, Parashock, which was actually dropped from a helicopter to verify durability. Three years later, Parawater became Japan’s first water-resistant watch with a rating of 50 metres. This was six years before Seiko’s first dive watch debuted in 1965, the 62MAS. In 1966, the Citizen X-8 became Japan’s first electric watch with a balance wheel regulated by magnetic coils, but it followed others like Hamilton’s Electric 500 in 1957 (to become the Ventura) and Bulova’s Accutron in 1960. It did, however, demonstrate Citizen’s serious investment in technology and it was blended with a world’s first in 1970 – the X-8 Chronometer with the first titanium watch case. At the time, titanium was a rare, space-age material and very hard to work with, so production numbers were limited to less than 2,000. It wasn’t long before Citizen developed new tools and methods to work with the metal and it has since been a leader in the space. There are dozens of titanium models today within Citizen’s portfolio, comprising “Super Titanium” or Duratect, a proprietary surface-hardened variant that’s five times harder than stainless steel. The brand was just getting started; however, quartz opened the floodgates for technological success.

Crystron Solar Cell and Eco-Drive

The first light-powered analogue quartz watch debuted in 1976, Citizen’s Crystron Solar Cell, which used eight miniature solar cells on the dial. This eliminated the need for standard battery replacements, which was both convenient and a big step towards environmental sustainability for the exploding quartz industry. It was the precursor to Eco-Drive, which remains one of the most advanced light-powered watch technologies today. It debuted in 1995 in Europe, Asia and Latin America before coming to the United States a year later, and the first Eco-Drive calibre 7878 was powered by solar cells hidden under the dial. The techy solar cell look (from multiple brands) took a back seat to conventional dial designs that made Eco-Drive appealing to a much wider audience. It was made possible by thin-film amorphous silicon solar cells that became efficient enough in the 1990s to rapidly charge by light through translucent dials (that appeared solid to the wearer). Initially, the solar cells were slightly visible at close inspection, but a world away from older cells mounted front and centre on the dial side. Titanium lithium-ion batteries allowed for a 180-day power reserve before requiring a light source for recharging. Many of the quartz movements could also go into a hibernating mode to conserve power after extended periods of darkness. In 2002, Eco-Drive VITRO allowed for truly concealed solar cells, so dials were indistinguishable from non-solar counterparts. By the mid-2010s, over 80% of Citizen’s portfolio was powered by Eco-Drive, with hundreds of different models available.

Eco-Drive Calibre 0100

At Baselworld 2019, for the brand’s 100th anniversary celebration, Citizen introduced a new high-end Eco Drive movement that was autonomously accurate to ONE SECOND per year. No radio signals or Bluetooth – it managed almost perfect accuracy all on its own. Let’s quickly jump back to 1975 when quartz was still relatively new. Citizen was already pioneering the tech, and just six years after the first quartz watch appeared, it developed the Crystron Mega with calibre 8650A that was accurate to just 3 seconds per year. An astounding achievement when mechanical watches at the time couldn’t even match that per day. Quartz accuracy in the 1970s averaged +/-15 seconds per month, so 3 seconds per year was extreme even for quartz. It directly influenced the development of Calibre 0100 with a special AT-cut quartz crystal that vibrated at 8,388,608Hz, which is 256 times faster than an average quartz crystal at 32,768Hz. The 1975 Crystron Mega’s crystal vibrated at 4,194,304Hz, so about half of the modern 0100. As we know with mechanical counterparts, higher beat rates are often better, but a high beat 5Hz (36,000vph) movement pales in comparison to a “high beat” quartz at over 8 million Hz (yes, that’s five vs. eight million). The 0100 is powered by Eco-Drive, so there won’t be fluctuations or disruptions from a low (or dead) battery unless you choose to live in a dark cave. Active Thermocompensation that tweaks frequency for temperature fluctuations and special shock protection contribute to the extreme accuracy.

The Citizen

The above is just a sample of Citizen’s innovations, but they emphasise its decades-long dedication to quartz technology. A relative handful of mechanical watches existed during this time, like the automatic Promaster Diver that used Citizen’s in-house Miyota 8200 series movements. However, with the proliferation of Eco-Drive, quartz equivalents like the Promaster Eco-Drive 200m Diver dominated. In 2021, the watchmaker released a high-end mechanical watch that bypassed the affordable segment and went straight into luxury territory, simply called The Citizen. It was a surprise move for this master of quartz, but also a perfect complement to high-end quartz models like the 0100. With a long history of mechanical watchmaking and one of the biggest (by volume) movement manufacturers with Miyota, high-end mechanical pieces make sense with neighbouring Seiko investing such an effort in the space. This also follows calibre 0910, released in 2010 to celebrate the 80th anniversary of Citizen watches (from 1930). That series represented a serious yet temporary return to high-end, in-house mechanical movements and was part of The Citizen premium line, which started in 1995 with high-accuracy quartz equivalents.

The 2021 The Citizen (ref. NC0200-90E) is a luxury integrated sports watch with calibre 0200, a new high-end, in-house automatic made in collaboration with Swiss movement manufacturer La Joux-Perret (Citizen acquired La Joux-Perret in 2012, although it continues to operate independently). It’s a time-only watch and accuracy is rated at -3/+5 seconds per day, so even better than the COSC standard. The 40mm watch itself is well finished with sapphire crystals front and back and a distinctive black textured dial. Priced at USD 6,000, it represented a big departure from the affordable automatic portfolio as it jumped into Grand Seiko territory. Of course, it was going head-to-head with comparable Swiss watches as well, especially with the La Joux-Perret collaboration. A broader mechanical portfolio, although still small compared to the entire quartz lineup, includes the affordable Tsuyosa Automatic (USD 270) and divers like the Promaster Mechanical Diver 200m that competes with Seiko’s Prospex Diver 200m (both around EUR 650). The recent Mechanical Day/Date NY4058 at only EUR 219 is also a competitor to many Seiko 5 collections.

Citizen has other product lines like Casio, including calculators, printers and CNC machines, while televisions, computers, handheld games and more were made in the past. The recent focus on mechanical watches, particularly high-end models like The Citizen, shows that a brand so heavily invested in quartz and Eco-Drive technology understands the growing demand for mechanical watches at multiple price levels. Citizen also has the history and name cachet to successfully carry high-end mechanical models, and its nearest competitor, Seiko, has been reinforcing that market for decades. It’s great to see mechanical watches thriving with the Japanese “Big Four” today – Seiko, Citizen, Orient and now Casio (with more to come from the latter).

Quartz Isn’t Going Anywhere

Let’s keep a healthy perspective here – there will never be a “Mechanical Crisis” that threatens quartz-focused brands. And all four brands listed above will never push quartz to the minority of their portfolios. However, what we’re seeing is a positive response to a growing consumer appetite for mechanical watches. The history, artistry and mechanical wonder have captured a new generation like vinyl and CDs. Retro is in style, and mechanical watches also have a prestige that’s hard to match with quartz – an heirloom vs. a tool, so to speak. I was surprised when Timex debuted the Marlin, but nearly shocked when Casio followed suit in 2025. And these aren’t just passing fads. We’ll continue to see growth in the space among quartz giants, and the industry as a whole is better off for it.

8 responses

The swiss watch industry is doing to itself what the Quartz “crisis” did back when. As the industry and its brands have taken full monetary advantage of my watch foible enthusiasm over time, I have lost my interest in the mechanical, and find myself shifting towards quartz. Which has the added benefit of widening my scope outside of the broken swiss watch industry amid its continuing arrogant and avaricious attitude. As these swiss watch brands continue their money grabbing to build themselves as many opulent palaces as possible, I find myself with a pleasurable sensation when I find a watch that interests me that has no connection to a broken swiss watch industry. And with the added benefit such as less servicing expense without having to put up with the same arrogance and avariciousness and rudeness when having to deal with these swiss watch brands service centers. If the quartz “crisis” or a different technological breakthrough causes another swiss watch industry demise, it will cause the smile on my face to become noticeable. One can only hope! Although I have found a chink in my attitude with a renewed interest in the Baume et Mercier brand solely because of it’s being discarded by “rich”mont.

I really enjoyed this article, especially the Casio segment, thank you.

Great acticle, well written and researched. Bravo!

Fantastic article, thank you. Maybe the most informative single piece on watches I’ve read.

Swiss thieves

Great article, informative and a fun read!

Wow! That’s a lot of historical info to pack into one article. Great job. In the big picture, it is interesting to see a surge in interest for mechanical watches. It is a different relationship one has with a mechanical watch than with a quartz watch. Aside from the luxury market, I am torn between which direction is the way to go. All factors considered, solar quartz may be the most environmentally sustainable. Maintenance on mechanical movements may not be practical for the mass market unless something like the system 51 becomes the standard? Even the Miyota 8200 series is sometimes cheaper to replace than fix?

Great article. Lots of info. For mass market watches, I’m not sure auto is the way forward? It is a different relationship one has with an auto than with a quartz. Manual wind is an even more intimate relationship, but you don’t see brands going there as much? There are reasons for both, and then solar quartz should be really considered another option as distinctive from battery quartz. Manufacturing costs, maintenance and sustainability will always be a part of the equation. Enthusiast nostalgia and luxury exclusivity will always be smaller segments of the watch spectrum.