The Work of Indie Watchmaker Alan Birchall & his Fully Handmade Watch Show a Promising Future

Even though we're talking about prototype watchmaking for now, it shows great signs of things to come!

There’s no denying that the love for independent watchmaking is on the rise. Throughout the past couple of years, we have also very happily seen a growing interest in artisanal watchmaking. Creating watches by hand, with traditional tools and techniques and hours and hours of labour. This time around, we have another new name lined up for you that ticks all these boxes: Alan Birchall. And despite being rooted in Europe and travelling halfway across the world throughout his life, Alan has settled in Japan to pursue his dream of making a watch completely by hand. With experience in the industry and a passion for the craft passed down through generations, his debut piece is nothing short of spectacular. And although the Pièce d’Essai No.00 is just a prototype for now, the work poured into it down to the finest details of finishing shows a very promising future!

Robin, MONOCHROME Watches – Alan, can you briefly introduce yourself?

I’m a 36-year-old watchmaker now based in Japan. My background is French and British. I grew up in France but moved when I was 20 to live in the UK and then Australia, where I became a citizen, and have now lived in Japan for the last six years, but I’m not Japanese. I’ve been a watchmaker for the past 16 years.

What got you interested in watchmaking, and what pushed you to pursue a career?

My father and grandfather are watchmakers, so it was part of my daily life when growing up. You have to choose at a fairly young age in which direction you will study in France. So at 15 years old, I had to choose without really choosing to go to a watchmaking school in France, as I felt I was more of a manual person. I studied watchmaking there for five years, and I quite enjoyed it. It felt easy too, but I quickly knew I wouldn’t want to work in Switzerland or work for my father at the end of my studies.

Can you talk us through the watchmaking journey up until your Pièce d’Essai N.00?

After my five years of studies, I went to the UK for four years to work for a big Swiss brand service centre where I serviced their in-house movements, module complications and perpetual calendars. I quickly got bored with this daily repetitive servicing work, and after reaching their highest complication, I knew I couldn’t stay there much longer. My options were to work for another Swiss brand with even higher complications, but still in a service centre, or move overseas again to open my eyes to the outside.

I went for a bench test in Sydney, Australia, and as soon as I landed, I knew that was where I wanted to be. I felt very lucky to get a job there. I was servicing watches, but not only for one brand this time and was able to service a very large range of watches. Working on recent and vintage Rolex and Omega watches, as well as high-end Chopard and Patek watches, the complications were much more interesting for me.

But I still had the desire to create something, and in my spare time with the tools I could get at the time, I designed and made a table clock with a traditional design, but showcasing the parts as much as possible. I stayed in Australia for six years and decided to move overseas to Japan for a short period. But it’s been six years now, and Japan is my new home with all the tools to make handmade watches.

Your first watch, the Pièce d’Essai N.00, looks absolutely amazing. What’s the inspiration behind it?

I think the main inspiration, aesthetically, is a mix of French and English watchmaking, which I was exposed to while growing up, including many British pocket watches and French clocks. Then it was very important to have a design that, to me, matches the manually operated machine used; the tools used shape the watch as well. Manually operated machines are extremely time-consuming, so I wanted to showcase the parts made as much as possible with an overhaul that has a pleasant appearance. Similar ideas I had when I made my table clock previously.

I also wanted to focus on the beating heart of watches, so a front-facing balance wheel was a significant part of the design. Mechanically and technically, I think inspiration came naturally from the thousands of watches I repaired, which gave me a deep understanding of what works in the long term. I saw almost unbreakable vintage movements and terrible new mass-produced movements, as well as what constitutes good and bad design. I have a fairly small wrist and enjoy small, elegant watches in general, so I focused my energy on creating a 30mm movement and a compact 35.40mm case.

Looking at what you share on Instagram, the movement looks handmade top to bottom. Can you explain what you do?

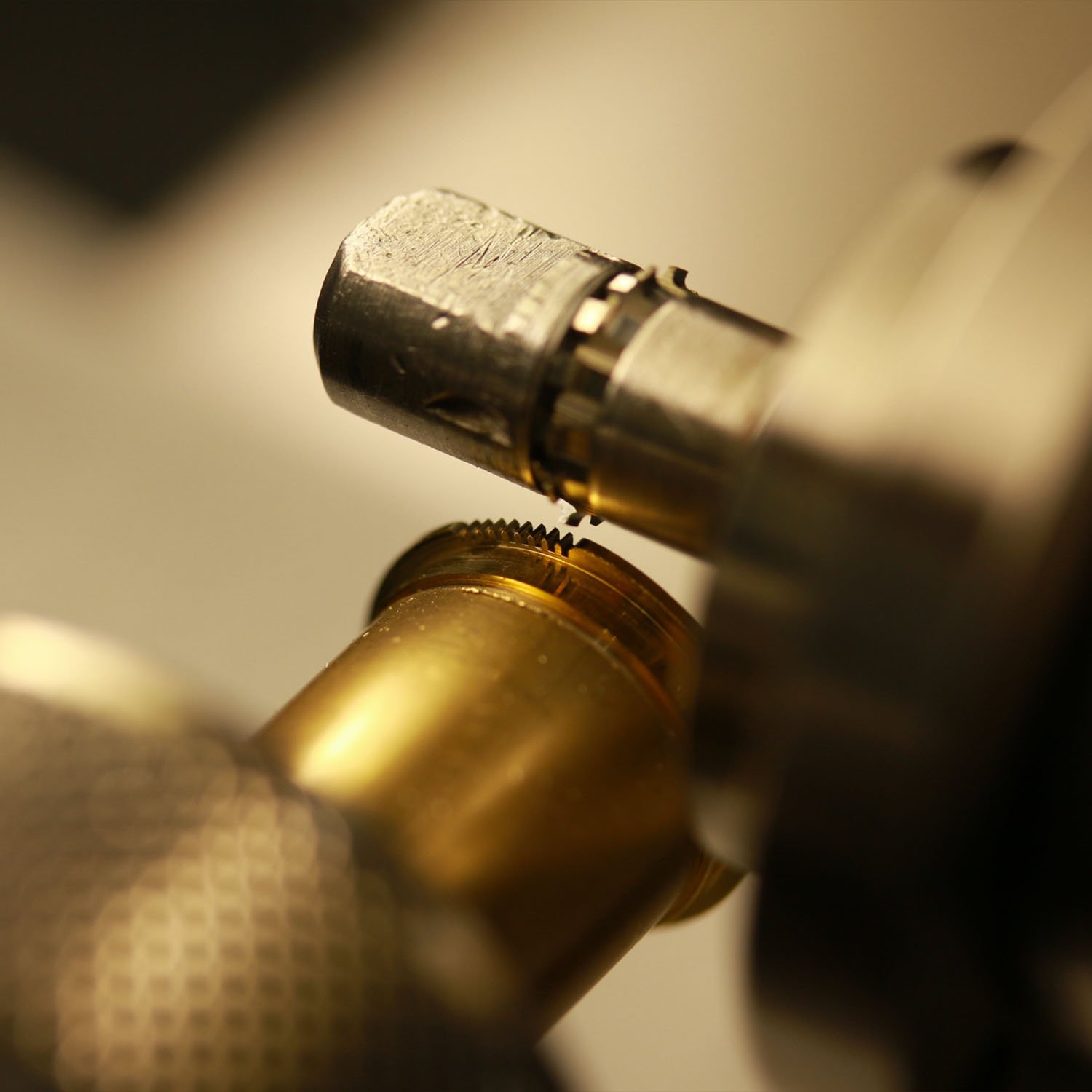

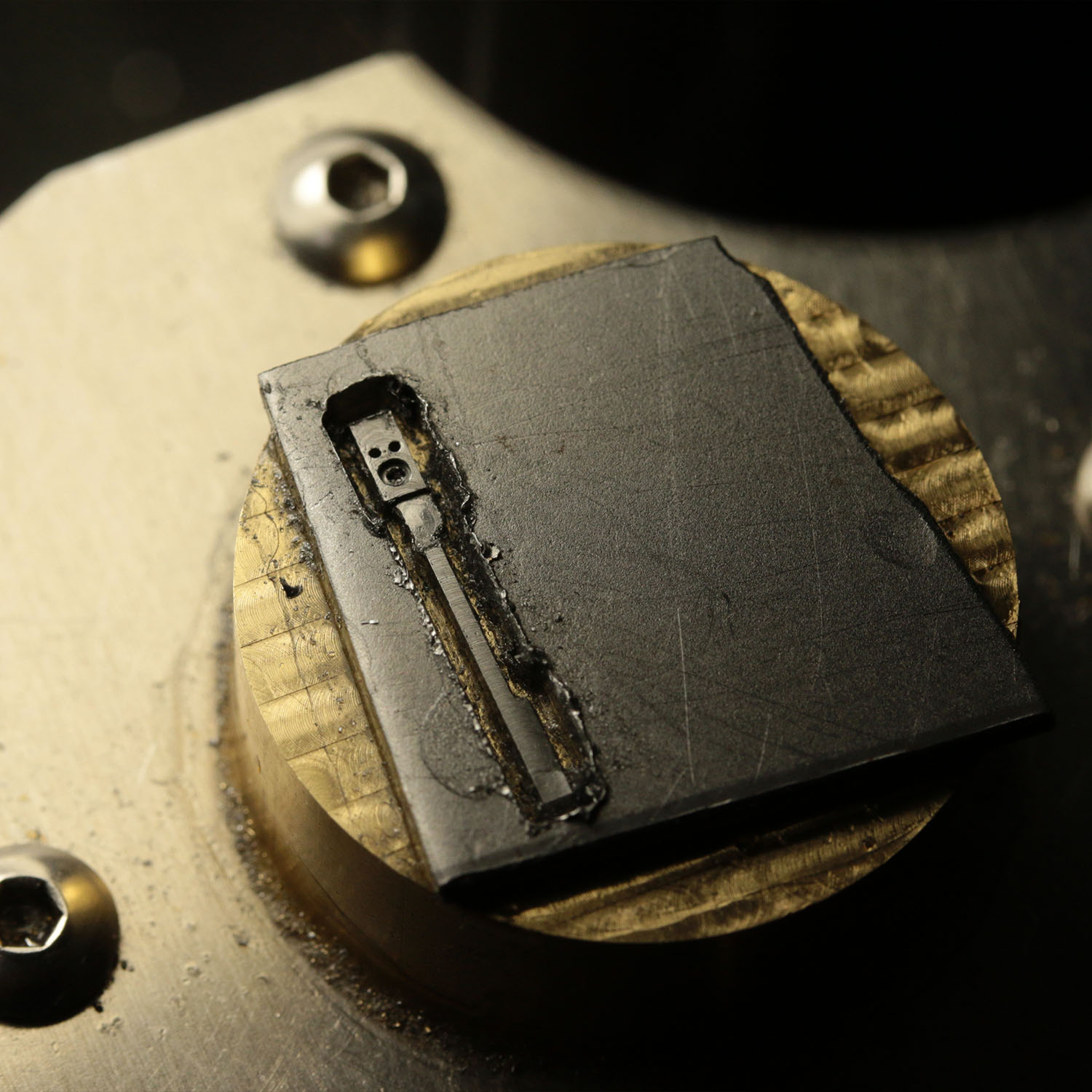

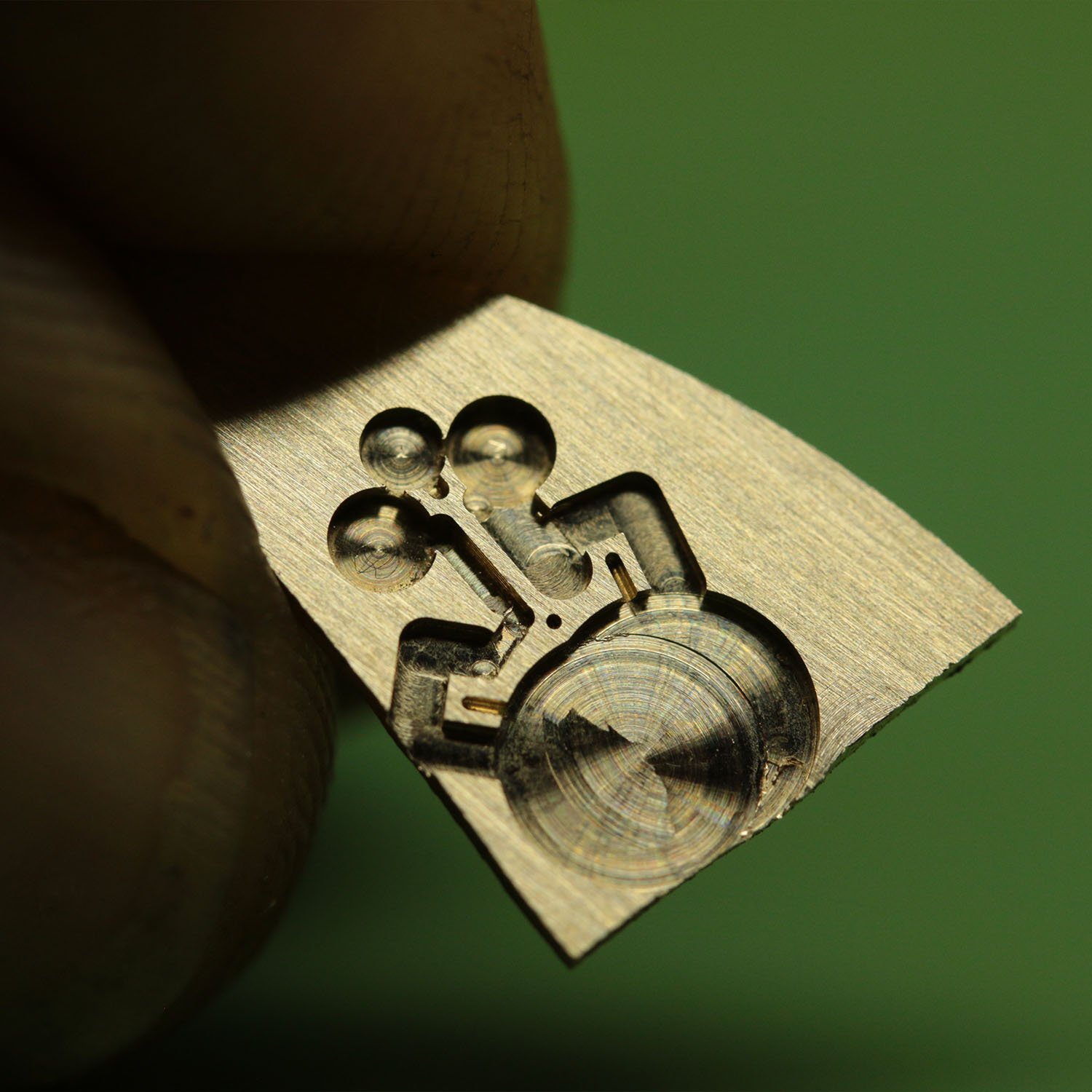

For this first watch that I made as a prototype, without including the jewel, crystal, hairspring, and mainspring, which will always be outsourced, there are 81 individual parts. I made 80% of those parts in-house without CNC, using only a hand-operated milling machine and lathes. The other 20% are outsourced parts.

And what about the dial and hands, as well as the finishing?

Finishing-wise, the possibilities are almost endless, as well. I made the dial and hands, as well as the case. The dial is satin-finished German silver. I’ve done the finishing myself, focusing on my liking for this one, a very long process as well, to find the correct overall balance. The brass parts are gold-plated with an almost matte-looking frosting and very delicate anglage. The train wheels and balance wheel are mirror-polished, not satin-brushed with anglage. Steel bridges and steel parts are mostly poli noir with sharp angles. The case is made of stainless steel in a 3-part construction with four separate lugs, all of which are mirror-polished.

What were your biggest challenges in making this piece?

The biggest challenge was time; it took me 2.5 years from the first sketch to the final watch. Prototyping on a manually operated machine is time-consuming, but it is highly rewarding in the end. Those machines are as precise as modern CNC machines, but human error is more important. And no error is allowed on the final parts. A very high level of concentration is necessary for a long period of time, learning to become one with the machine.

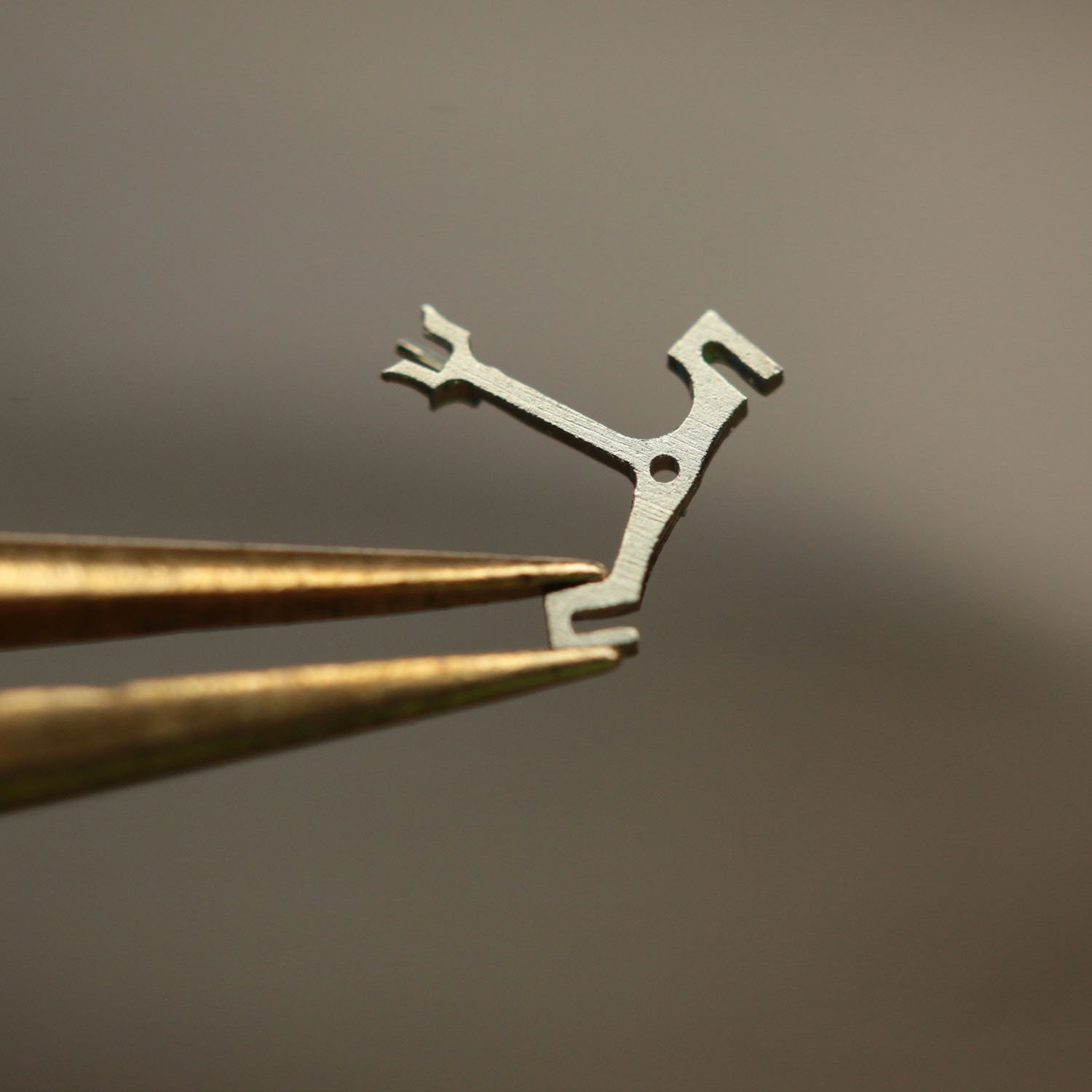

Many variations of parts need to be made during prototyping as well, increasing the number of parts that have to be made before a final watch. Probably the most challenging part to make is the pallet fork, milling with a 0.25mm endmill, drilling with a 0.105mm drill, and then doing all the finishing. Hours and hours of work went into that tiny component, but it was a joy when completed!

What’s the goal with this watch? Is it available for people, or will there be a small run of watches?

The goal was to challenge myself, test my capabilities, as well as the machines I use. I wanted to make a watch in a way that is interesting to me, with a design that I enjoy. And now hopefully other people can enjoy it as well. As a prototype, this one is not available. I’ve been wearing it often to see what needs to be slightly changed, where I’m fully confident, and where I believe improvement or design change should be made.

What’s the next step? Any ideas on future models already?

I’m currently on the next step, making number 1. It will visually resemble the original, but will be tailored to the client’s taste for finishing and any ideas they may have, such as a larger case, for example. However, I am currently working on producing 20% of the outsourced parts myself, so they will be on par with the rest of the watch: in-house and handmade. I’ll then be taking individual orders, one by one, all unique. After two and a half years of work on the prototype, I want to make a few of these models available. But I have plenty of other ideas in my mind, which are slowly brewing.

In the long term, what do you hope to achieve in your watchmaking adventure?

I hope I can connect with people who are interested in this kind of watchmaking and who support independent watchmaking. And I would love to be able to keep building an even more special workshop. I enjoy seeing the process and progress in individuals’ works. Seeing the first watches of the current big independent watchmakers to their most recent one, or in other fields of work, for example, seeing a ceramist artist progress curves in their work, is beautiful.

So, I really hope I will be fortunate enough to make watches the way I like for people for as long as I can. And one day, I hope to look back on my previous work and be fully satisfied with the process. My finishing level, for example, has already progressed a lot for the next one, and I’m already happy to see those slight changes.

Do you have any final thoughts? How can people get in touch if they want to know more or express interest in a watch?

I just wanted to thank everyone along the way. I am always happy to get in touch via my Instagram account or through my website, A.Birchall.com.

3 responses

sometimes “less is more” but this time is not. meeh

I tend to agree with Sajzija. The dial side and the back project the same picture : High quality hand finishing of mechanical work. Were it not for the two hands on one side and the gear wheel on the other one could almost confuse them.

Anything open-worked is OK by me, and this is fantastic. If two hands and a gear wheel are the only thing preventing you from being confused about which side is which, Lucien Fa, maybe you need to see an optometrist, or a neurologist. Sheesh.

That aside, not a fan of the “tell us who you are” interview (isn’t it the job of the writer to ferret that out?), although I see why you do it that way with him being Japan.