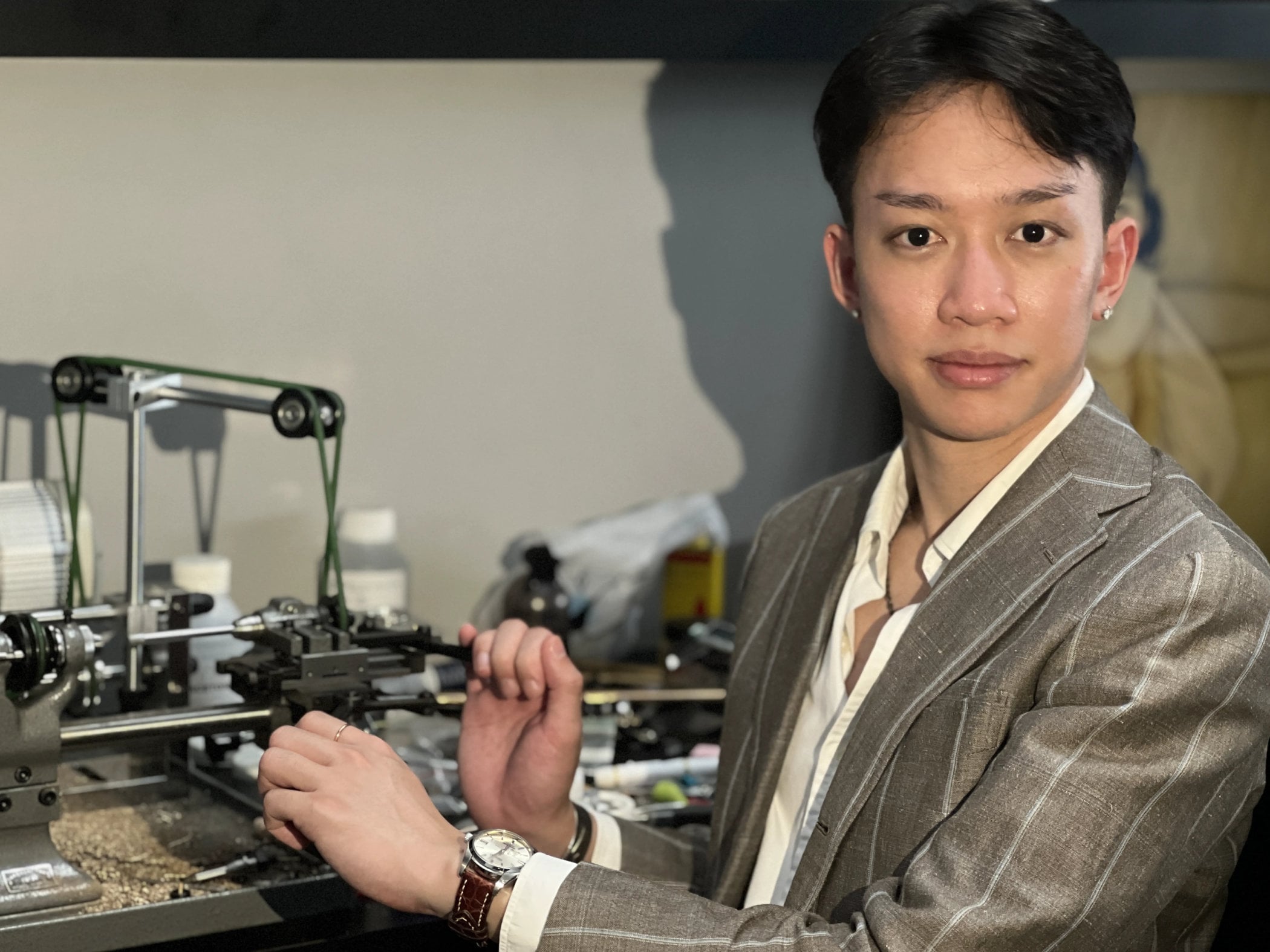

Singaporean Indie Watchmaker Tristan Ho, Founder of LOTH, Debuts with the LOTH1

A young self-taught watchmaker from Singapore who went from modding Seikos to creating artisanal hand-finished watches.

The world of independent watchmaking is a global phenomenon, that much we know. With the internet connecting all corners of the world, we get to meet new people, discover new watches and ultimately share them with you, of course. This time, we travel to Singapore, a place with a buzzing watch community and a strong sense of creativity, as showcased by the many (micro) brands originating from the island city-state. New to the game is Tristan Ho, who not too long ago founded LOTH, or Lab of Tristan Ho, in pursuit of his own independent watchmaking dream. And what starts out with something as simple as the Unitas/ETA 6498 is set to evolve into Singapore’s first in-house developed movement. Talk about ambitious…

Tristan is a young man who comes from a very different field of industry, as he is a trained biomedical researcher. Combining a deep admiration for traditional watchmaking craftsmanship and meticulously hand-finished components, he founded his own brand in 2024. Years prior to that, the journey began with the decision whether to buy a fake Rolex or not (the answer was ‘No!’, obviously). This encounter, after knowing little more than Seiko and G-Shock, mainly through his father, sent Tristan down the rabbit hole of watch discoveries. Not liking what he could find within budget at the time, he decided to build his own and started working on a modded Seiko NH35. Fast forward to today, and we find ourselves with the LOTH1, Tristan’s first commercial watch.

Robin, MONOCHROME Watches – Tristan, how did you get introduced to watchmaking, and what pushed you to pursue a career in it?

Three years ago, when I was on holiday with my girlfriend, we passed by some street vendors peddling fake Rolexes. I still remember the seller telling me it is an automatic movement, with ceramic and stainless steel. Back then, I did not know anything about watches. I did know that Rolexes were expensive status symbols, and I thought getting a fake one for $200 was a great deal, so I asked my girlfriend if I should get it. However, she said “no”. I returned back to Singapore empty-handed, with the itch to buy my first mechanical “big-boy” watch. I spent most of my free time researching what the best value-for-money watch on the market is, but I mostly came across brands using ebauche $200 movements, charging high markups. Hence, I decided to make my own watch.

I started out with Seiko NH35 builds for a few months, but it wasn’t enough for me. I have always felt that the movement of a watch is its soul, and I wanted to wear something meaningful, not something mass-produced in a factory. That’s when I discovered Instagram videos of Felipe Pikullik and Minhoon Yoo doing movement finishing, and I immediately knew it was what I wanted to do. I gathered as much information as I could from those few seconds of footage, took note of what tools I needed to purchase, and had my first start attempting anglage around two years ago. Perhaps it was my innate fascination with micro-mechanics, nurtured by a Lego-rich childhood, that caused me to immediately fall in love with the craft.

Since then, I have been avidly pursuing watchmaking, learning as much as I can from the internet and from my own experimentations.

How did you learn the skills to create your own watches?

Almost everything I know today is learned from the internet. I still have a day job as a biomedical research assistant, so I don’t have the resources to go to watchmaking school. Instagram reels showcasing the process of other independent watchmakers like Felipe Pikullik and Minhoon Yoo were what inspired me to make my own watches in the first place, and to me, they contain a wealth of knowledge. I study them intensely, take note of the tools they use, purchase them and try to replicate what I see. Most of the learning process is trial and error; I had to experiment a lot to get the perfect results. For just my snailing, it took me about 1.5 years of R&D to develop.

So you’ve worked with several of the young and upcoming names in the industry! What stuck with you the most through those experiences?

I have talked with fellow independent watchmakers, asking them for advice or even just picking their brains about watchmaking in general. Everyone is so friendly and willing to offer help out of genuine shared passion for the craft, and my timepiece would not be anywhere near possible without their help. A huge thanks to Michael Dubs, who took an afternoon to teach me how to polish screws; and Ondrej Berkus, who carved out time in his busy schedule to refinish and ruthenium galvanise my mainplates in the process of moving to another country. Their generosity amazes me, and I make it my mission to pay that kindness forward.

You told me the first thing you attempted was anglage, which is far from the easiest starting point. Why anglage?

The first thing that drew me to movement finishing in the first place was videos of inner angles being done. Honestly, it seemed like the easiest to start out attempting, as there is no complicated machinery required, only hand tools and patience, compared to something like snailing or perlage.

Your first watch is the LOTH1, which relies on the ETA 6498. What can you tell us about the inspiration?

For the movement, I wanted to create something with generous inner angles, and I looked at the shape of the Lang & Heyne Friedrich III as a reference on where I can include them. Everything is still designed by me from scratch, with only the coordinates of the 6498 components as a template. Every curve is based on a mathematical formula to ensure the most cohesive combination with the jewels and gear wheels. For the dial, I knew I wanted a two-part dial with a chapter ring for a 3D look that has depth. I went with dots for the hour markers after coming across a picture of the Bakkendorff Byrja, as I find it elegant and yet gives off the honest, homemade look that I appreciate. Combined with the raw-looking grattage on the base, I find it reflects my journey as a self-taught watchmaker well.

The plates and the dial are crafted from German Silver, except for the chapter ring, which is stainless steel. I chose these materials because they don’t require electroplating, allowing me to showcase the raw characteristics of the metals. I like the idea of permanence, and this is how I ensure my parts can be easily refinished centuries from now if need be. Even for my dial, I refused to use glue or any other adhesive to attach the two parts; instead, I put the dial feet on the chapter ring and sandwiched the dial between the base and the mainplate for ease of servicing and repair.

The dial shows a rather interesting texture, which is also found on the back. How did you create that?

This is a variation of the traditional grattage finishing, which I term “mosaic” finishing. To achieve this, I made my own homemade cabrons, which are lapping paper adhered onto wooden sticks, and cut the ends into the desired shape I want. I subsequently apply each scrape to the dial by hand, while also regularly refreshing the abrasive end by recutting the cabron every few strokes. As adjacent strokes cannot be facing the same direction, this method requires me to plan 4-5 steps ahead to make sure I don’t “checkmate” myself.

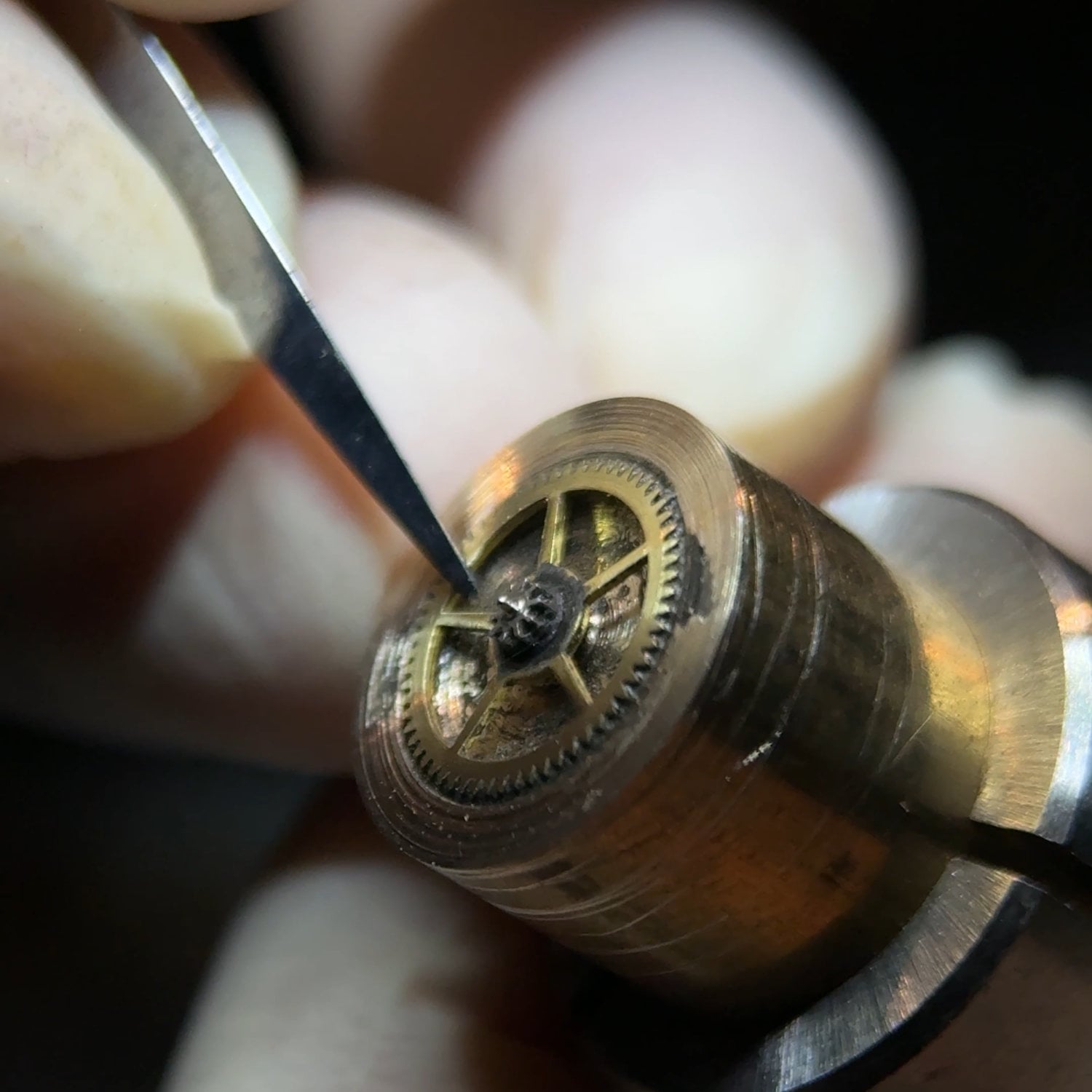

The movement finishing is rather impressive! Can you explain what you did to the movement?

The plates were made by CNC, and I subsequently frosted the surface by hand using abrasive powder on a glass plate, the traditional way. Compared to sandblasting, this leaves a unique microscopic topological structure that interacts with light in a unique way. I then cut the bevels by hand and polish them. I do not allow the CNC machine to cut the bevels as it would produce rounded inner corners. I maximise the thickness of my bevels, rather than keeping them thin like most brands do, as I don’t want to produce an anglage only visible with a loupe. As a result, finishing all the plates takes around 100 hours per watch. I cut the countersinks by hand and polish them too, so more light enters the jewels, improving clarity and colour of the synthetic rubies. The train wheels are refinished with circular graining and very light burnishing on the spokes’ bevels. The balance bridge features mosaic decoration to create a cohesive aesthetic with the dial. The crown wheels are snailed, and the ratchet wheels are double snailed, and all the screws are black polished and bevelled. After finishing each component, I check it under my stereo microscope to ensure it is satisfactory before assembling the movement by hand.

For the watchmaking aspect, I have to reset the jewels with the appropriate amount of endshake, at times adjusting them to the micron level to ensure the movement’s performance. Proper lubrication is an often overlooked area too; I have to grease the keyless works and the ratchet mechanism with the perfect amount for the best tactile experience possible with the base 6498 components. I take extra care with the jewel pivots, as too much oil would not only affect performance, but might cause the oil to run onto the surface plates and tarnish them, which I have seen happen to other, much more expensive watches.

The watch was for sale but is now sold out, as I understand it.

Yes, the watch was for sale. I launched at the end of April and officially sold out by the start of September. In fact, this series has been oversubscribed by more than 100%. I am very grateful for the support and encouraging response from the horological community around the world, and look forward to making many more timepieces for the rest of my life.

After this one, what’s the next step for you?

I plan to make Singapore’s first in-house movement and will work on it incrementally. The next challenge for me will be to design my own mainplate, giving me more freedom to change the movement’s architecture.

What do you dream of achieving as a watchmaker? How do you see yourself evolving?

Other than making Singapore’s first in-house movement and putting my country on the world map of haute horlogerie, one of my biggest goals is to inspire a new generation of young local watchmakers and show them that there is more than one way of becoming a watchmaker, other than going overseas and spending tons of money at watchmaking school.

Any final thoughts to share?

I hope my story reminds others that there’s never just one path to success. Whether in watchmaking or any other pursuit, stay curious, keep creating, and don’t let convention limit what you believe is possible. The most meaningful work often comes from simply doing what you love.

How can people get in touch with you to learn more or reserve one of your watches?

My Instagram direct messages are always open to fellow budding watchmakers, to feedback and constructive criticism, and collectors who are interested in getting a piece or who just want to chat about horology in general.

For more information, please visit Loth.sg.

2 responses

Always enjoy reading about up and coming watchmakers! Have seen Tristan’s handiwork up close and personal and while the case can still be refined further, you can really see the amount of work that’s gone into his finishing, keep it up!

Very nice work! You can see the passion and attention to detail he puts into his finishing. I can see great things coming from Tristan!