The Horage Supersede GMT Sports Watch, With In-House Micro-Rotor Calibre

An in-house Swiss micro-rotor with multiple complications and bold design.

Hot off the heels of the Tourbillon 1 (and Tourbillon $1), the most accessible in-house Swiss tourbillon (less than 8K Swiss Francs), Horage is introducing the Supersede GMT sports watch and its K2 micro-rotor movement. The company believes in community feedback and allows watch enthusiasts to vote on final design elements (colours, finishing, etc.), and Supersede is no exception. Such close involvement with the community is rare in the industry, especially with high-end pieces, and Horage is certainly a rare breed. Let’s have a look at the new Horage Supersede GMT Sports Watch and its in-house K2 Micro-Rotor Calibre.

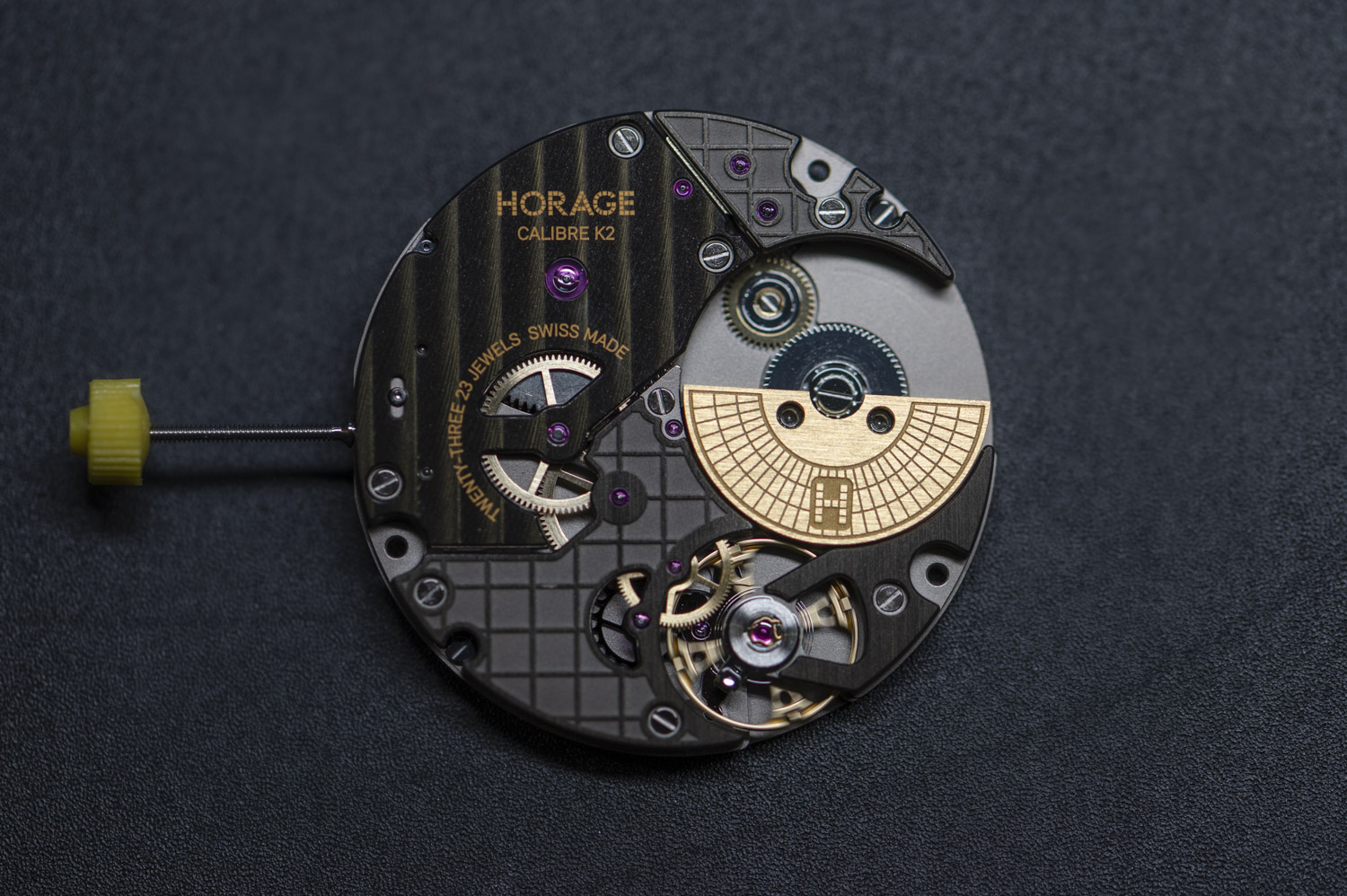

Starting with the K2 engine, the brand has designed a micro-rotor calibre with a silicon escapement, which includes the hairspring (and escape wheel and anchor). Seen through the sapphire case back, the movement has a stealthy, futuristic aesthetic. Everything is blacked out with contrasting gold coming from the micro-rotor and select gears, and there’s a well-placed jewel on the top plate (HAL 9000 vibe). Decorations include Côtes de Genève and Horage’s signature grid design. It all culminates into one of the slickest looking movements I’ve seen recently.

The movement has 23 jewels, beats at 25,200vph (3.5Hz) with a 72-hour power reserve. Functions include an independently set GMT hand, day/night indicator, power reserve indicator and date. This is a modular movement with 38 possible variations and the base movement is only 3.6mm in height. The K2 is the brand’s third in-house calibre, following the K1 automatic and K-TOU Tourbillon, and all are accurate to COSC specifications: -4/+6 seconds per day. The community can vote on whether the K2 gets an official COSC certification, although it will meet the standard regardless.

The Horage Supersede GMT is an “all-terrain” sports watch, designed to go from the board room to hiking trails to a weekend of diving. It starts with a more unusual 904L stainless steel case (a Rolex favourite) that’s more corrosion-resistant than 316L with a better sheen when polished. It will certainly be very wearable at 39.5mm in diameter and 9.85mm in height, and water resistance is currently rated at 100 metres. Horage is working on doubling that for production models. There’s a rotating diver’s bezel with a detailed 15-minute scale that sports a unique knurled pattern with two rows of bevelled rectangles. The crown is protected by full guards and has the brand’s logo embossed. There’s an integrated three-link stainless steel bracelet that completes the refined, sporty aesthetic, while sapphire crystals cover the front and back. The final bracelet design will be based on the community’s votes – either brushed or polished links.

The dial has multiple complications but remains clean and uncluttered. The GMT hand is about the length of the hour hand and open-worked in lieu of the more common “red triangle” design. Applied indices and the hour and minute hands have Super-LumiNova, along with the triangular marker on the bezel. The seconds hand has an orange tip, matching the day/night indicator’s hand at 9 o’clock. The power reserve indicator sits at 12 o’clock and the date at 3 o’clock. Dial colours will also be voted on with three out of six being chosen for final production – 12:00 (white), 24:00 (black), Jet Stream (grey), Boreal (green), Atoll (light blue), and Transatlantic (dark blue).

Preorders for the Horage Supersede GMT Sports Watch start in November 2021. Early bird preorders will start at CHF 4,500 with a retail price of CHF 6,500. For more information, visit Horage’s website.

10 responses

Okay, hope someone at Horage is reading this. You can’t use the term ‘In-house’ as you do…well, I mean you shouldn’t; you *can* continue doing it if you like but it’ll just annoy people like me who go digging when something seems a little…gilded.

I know that La-Joux Perret reneged on a deal with you for either the K2 or the Tourbillon – can’t remember which – so I guessed they had nothing to do with this final calibre. It was the unusual 3.5Hz beat rate that led me to discover whose ‘house’ has possibly been used: apart from Omega the only other set-up of true manufacture standard that I know consistently uses that beat rate is Armin Strom, unsurprisingly located close to your address in Biel.

From there the search for info becomes easy. And, if you still have use of their premises, I think you should mention them, rather than go this semantically-murky route – they’re fantastic and for me any connotation with them is a good thing, especially for such a young brand. You’ve clearly got talent on your payroll (industry veterans I believe) and should take credit where it’s due for design and even creation of certain aspects, but be open! You are working with an impressive set-up.

So many things to love about this watch but I am still warming up to the design. Can’t wait for some hands on videos and pics.

Pretty impressive! I love the dimensions – why couldn’t Tudor do this with the BB GMT?? Also to correct the article this is a true/traveller’s GMT watch with a local jumping hour hand – went to the web site and checked out the animation. Actually makes it more impressive to me. Not a fan of the integrated end links though.

Or, maybe Armin Strom no longer have anything to do with the K2 components, and it’s purely down to THE+AG. If you’ve reached the stage that you can completely independently make movements now, then I apologise for my cynicism. I thought it was cases, dials and bracelets THE+AG made, wasn’t fully up-to-date with any progress towards the full kit and caboodle.

The investment that must’ve taken…massive. Hat’s off if so.

Dear Gav,

Thanks for the questions you bring up and as you can see we indeed read the comments. In my role as CEO and initiator of Horage as well as its associated movement projects K1, K2 and KT, perhaps I am in a good position to clear up some of your questions. However since our story dates back to 2007 and beyond, I will not be able to go down every rabbit hole in full detail.

Upfront I want to talk about the heavily abused word “in-house” and I agree with you, that it is misleading and should be used carefully. I personally do not like the word and I think the industry and media landscape did itself not a good favor in the way it defined and communicated its meaning. At the end of the day I think there is no company in Switzerland, which delivers premium industrial scale modern movements while doing everything inside of its own organization. The degree of expertise needed to industrially produce all the various components that make a movement can hardly be mastered by one company alone. It is not only a question of cash, rather than know how acquisition, development and conservation. And since technologies in manufacturing evolve constantly, typically the specialized suppliers are the ones who acquire specific know how more quickly than a large scale organization trying to do everything. These suppliers are the basis for the Swiss watch industry because they are the ones who can scale it across more customers and make it available to engineering driven companies like us. Knowing the suppliers all around us I can assure everybody that even the best, to which I count Rolex and Omega, source lots of parts and know how from the vendors around them.

When we started our K1 movement venture, we had to make some very basic decisions. It was clear to us that an industrial level product needs a very different approach compared to making a manufacture movement only. Typically we look at 7-10 years to mature an industrial movement, especially when you are a team of rookies as we were. Many people think that when you have a bunch of machines, one is capable of producing a movement. This misguided believe is perhaps the reason why most movement projects have failed in the past. Furthermore we can see that hardly any components supplier managed to get into the business of making complete movements. We asked ourselves what are the critical success factors to bring an industrial level movement design to life and survive the expected very long time period until you make it to the market. I identified 6 fields on which we had to make up our minds how to deal with them.

So what are the really relevant skills we would have to master within our team to get a chance for success. (1) Design/Engineering (2) machining (3) supplier management (4)Quality control (5) T0-assembly (6) T1-assembly. Since the movement business in my opinion is a “die-hard” process and tolerance business in the first place and a machining exercise in the second place, it was clear to me that we first should try to control every aspect of this business except machining itself. Only if there would be no available supplier within reach or because of political reasons not accessible for us, we should buy machining equipment. We held true to this rule until today although recently we have started to build up know how for machining like milling and turning. We do this to increase our speed in bringing new movements to life and because we feel ready to do so after more then 12 years since we have become pretty good in all the other mission critical areas listed above.

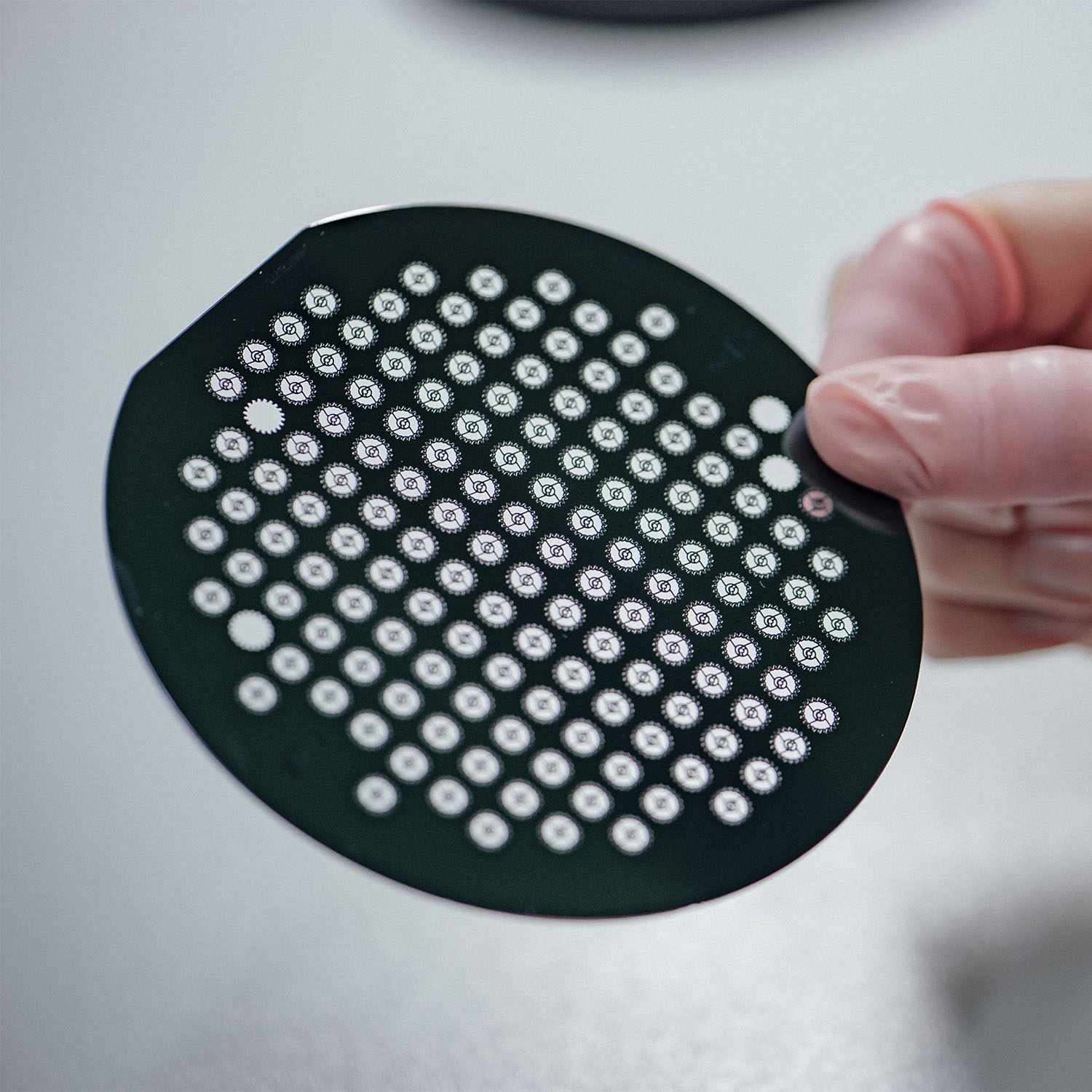

Unless many others, we did not buy a movement design from an external engineering company or cloned some existing designs. We designed from the ground up by ourselves, we assured that we understand each and every manufacturing process, we learned how to control the quality within each manufacturing step, we built the tools to perform all T0-assembly steps and we run our own T1 assembly. Many in this industry buy complete assemblies from vendors and we decided not to do this, because it is crucial to understand all the steps in between a part coming to life (milling, turning, gear-cutting, de-burring, washing, rolling, heat treatment, plating…) I can fairly say that we really understand every process of each component and we work very closely with approx. 30 suppliers mainly from the region to create the best possible mechanical design that fit their requirements and machining capabilities. We see the principles of Design-to-manufacture, Design-to-cost, Design-to-performance as some kind of decision-triangle in which you constantly have to make trade-offs between these three methodologies to produce the best possible outcome.

We started out with an engineer and a computer in 2008 and we formed many fruitful partnerships amongst one of them with Armin Strom. This partnership lasts until today and some of our early followers know from our Kickstarter campaign in 2015, that we actually were embedded in the facility of Armin Strom for many years developing technical solutions, manufacturing methods, warehousing and assembly methodology together. This friendship lasts until today and is very unique for both sides, because both sides profit from this intensive exchange of ideas and solutions. Even several of our team members move back and forth between Armin Strom and our organizations. Besides Horage, we had to funnel our movement projects through several organizations, as we tried to find financial investors along the way. However we recognized that mostly such investors did not understand how challenging it would be to build an OEM movement business and thus we had to shut down several of these companies along the way. Horage and the team however always sticked together carrying on with these movement projects.

We consider our movements to be our own, because we are able to create them with our brains, we source all components from trusted suppliers and we control T0 as well as T1 in its entirety. There are not many companies in this industry who can control all T0 processes in-house and I am particularly proud of this and our entirely proprietary engineering, because this is where the true know how in movement making is hidden.

I will talk about the origins of why we use 3.5 hertz in another comment, because now it is time for a nice Saturday evening barbeque?

Andi

Dear Gav,

I would like to reply in detail, but either my explanation is too long or it needs review first… not sure.

I am Andreas Felsl, the CEO of Horage.

Flippin ‘eck, consider me educated Andreas. Superb reply, I didn’t expect that – thank you very much. It’s not too long (twitter has ruined us) and I enjoyed reading all of it. Looking forward to learning about the 3.5Hz origins.

I’m sorry to ask something else – tangentially related to beat rates – but I was wondering what considerations are given to the decision to use a free-sprung variable inertia balance versus an index-regulated smooth balance. From what I could gather from looking at pictures of the K2 calibre, you seem to have elected to use the free-sprung option (correct me if I’m wrong of course!) which I hold in high regard.

*edit* Oh I see what you meant by the comment maybe being too long! Frank or Brice would’ve had to probably do the due diligence to check that spam doesn’t get through, and since you posted it at the weekend they were off duty. Living La Vida Loca most likely. 😉

Hi Gav,

Yes Twitter has ruined the art of writing in some ways ?

Lets talk about the 3.5 Hz… When we started out conceptualizing the K1 in 2008, we tried to imagine how a movement needs to be 10 years down the road. At this time and until today, most watches are built on Nivarox based 20.3 escapements and 4Hz balance systems. However Omega at this time was the first to go into the 3.5 Hz realm in combination with their Coaxial. Besides the advantages of the co-axial, there are also some draw-backs in efficiency, because at the end of the day the original idea of a lube free escapement did not play out as thought. Which means a 4Hz beating Co-axial would likely suffer from less available power-reserve when used with the same form factor main spring like we know it from the 2892 movements. In combination with a 3.5 Hz beat rate and the increased precision in manufacturing they could bring up this available power reserve to a good level.

Somehow our reasoning was that available power reserve is an important factor in times where people own more than one watch and want it to continue to run over the weekend without having to wind. 3.5 Hz could deliver this while still allowing us to easily pass COSC. Through our friend Kilian Eisenegger we got in touch with a supplier called MHVF which actually offered a proprietary escapement in combination with a 3.5 Hz beat system. So we chose this and I think we were the first ones after Omega going for this beat rate which we think is a very good trade-off between the widely used 3 Hz and 4 Hz. 3Hz is not easy to get through COSC and 4Hz has more known maintenance issues when it comes to wear and especially lubrication like many other fast beat systems.

In 2010 we showed the first time a prototype of K1 at our little secret Horage event at Schloss Binningen during Baselworld. Not many people knew about us, except Serge Maillard from Europastar who followed our story and later wrote an article about us in 2013. https://www.europastar.com/magazine/features/1004086529-exclusive-a-new-movement-accurat-swiss-operation.html. At this time we operated under the name Accurat Swiss which later was liquidated.

We actually worked with MHVJ in the beginning because we couldn’t buy anything from Nivarox, as we didn’t have COMCO imposed rights like other established movement makers which allowed them to by from Nivarox. In other words we were nobody’s and nobody took us very serious. Understandable somehow.

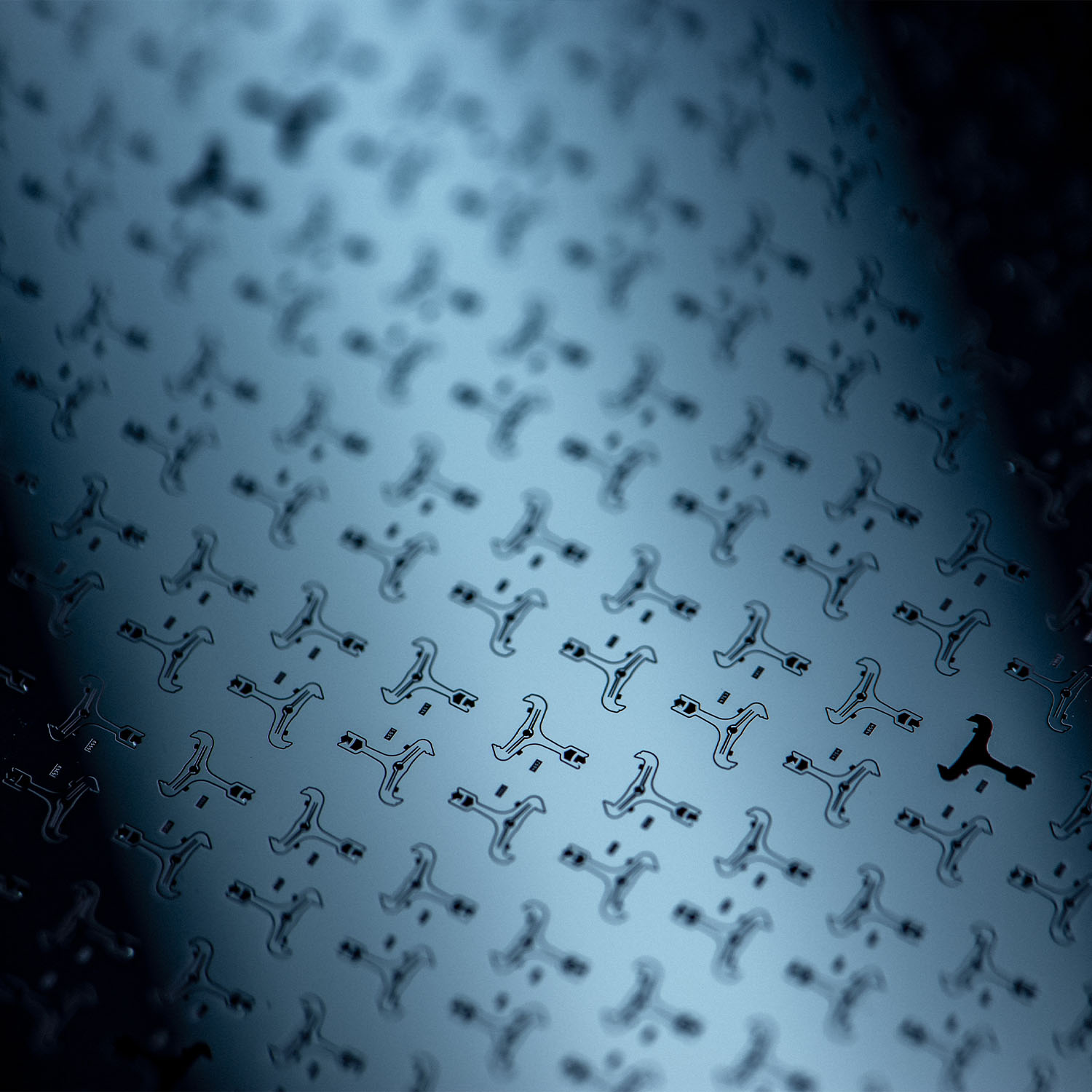

During this time MHVJ was taken over by the Festina Group and Kilian left MHVF which again would put us into a very critical dependency on these fundamentally important core components. Again we had to look into future technologies and since we observed the ongoing silicon discussion, we decided to go down this road and acquire all the necessary know how to design and build silicon based regulating systems, which form today the foundation of our know how. We started with index adjust however it is harder to regulate to COSC level especially in combination with steel hair springs. Weight of the spring plays a very important role in the hanging positions and needless to say silicon is not only the future with escapements but also and especially with the hair spring. We sticked with index until we better understood all the physics and maths behind the regulating technology.

At our 10 years anniversary we then took our know how to a next level and developed a masselot based regulating system in the Autark 10Y edition which bridges are signed by Jonas Nydegger and Florian Serex the engineering drivers behind our development exercises. It became clear that a regulating system with fixed length spring delivers better precision during regulation and in the different positions compared to an index type system. But it is awful to regulate, because the masses are not linear in their weight distribution compared to radially mounted screws when doing the adjustement. Having learned enough about the masslot systems we then decided to move to a screw based system. Masslot and Screw is more or less the same principle, however we put a lot of focus on user friendliness and producibility. After long internal optimization period, we first time used this screw balance system in the Tourbillon and this system will serve as our future regulating system of choice. It ticks all boxes for us.

It was not at all our plan having had to develop all this know how. It is a long and painful process and in fact besides the biggest guys in the field, there is nobody who develop all this know how in-house. We did it because we like engineering challenges and we wanted to make sure that we understand really every single component in our movements, because only then we can remain 100% independent and improve our own work on a continuous basis. The fact that we master this know how within our team was the reason why we could realize a Tourbillon within 8 months, because this know how is fundamental to design a modern high performing Tourbillon. Needless to say this is also the reason why many companies can’t develop tourbillons and just buy some off the shelf stuff because they lack the core know how in the regulating technology.

“Heavy lifting” is a mild explanation of our engineering history and I totally understand that sometimes we are observed with a critical view, because it is hard to imagine that someone is flying below the media radar for such a long time and then just comes out being capable of cranking out advanced industrial scale movements including all the regulating tech. But it is like it is and everybody can come to us and convince himself about our capabilities. Today, when looking back at all this I think if one wants to play in the top league of watchmaking one must master first and foremost the engineering side of things in its entirety. This is where the value is being created and this defines in-house for me. Because a company which e.g. clones movements or key assemblies and at the same time is able to produce a couple of parts in-house does not necessarily have the intellectual capacity of designing something new or significantly improve existing movements and the workflow coming with it. There is nothing bad about that, because engineering a multi-parts component at micron level as we it has do be done in the industrial movements business is hard… very hard.

Exciting discussion here?

Thanks

Andi

@Andi

Wow, yes, you have definitely done the ‘heavy lifting’ to get to this point. I was nodding my head in recognition of your reasoning behind greater power reserve for those who own more than one watch, the COMCO situation, and the decisions required when going for COSC testing. Long live 25,200vph I say.

You certainly have had a tough time when it came to relationships with suppliers, I sympathise greatly. But you wouldn’t be who you are today without those bumps in the road to make you forge your own path I suppose. Reading about your engineers developing the Autark 10Y masselot/screw system is fascinating – I love learning more about these technical aspects, especially when it is something that aims to improve the calibre in a meaningful way.

You’re a team of proper engineers and lovers of the mechanical watch, and I admire that.