The Top Five Countries Where Watchmaking Reigns Supreme

There have been significant shifts in watchmaking leadership over the centuries, but five countries reign supreme today.

There was a time when America was one of the dominant horological countries, from the mid-19th to the early 20th century. That’s no longer the case, of course, but there’s been a small yet impressive comeback in the high-end space from RGM Watch Company, J.N. Shapiro and Keaton P. Myrick, among others. Switzerland is synonymous with watchmaking today, and is the current leader (at least in terms of image, probably not in terms of production scale), and several other countries are also dominant and cast shadows over the rest. That doesn’t mean that impressive watchmaking doesn’t exist elsewhere (and we’ll talk about that in this new episode of the ABCs of Time), but the biggest fish in our global pond reside in five countries that have firmly planted their horological flags.

Switzerland

“Swiss-Made” is the ultimate stamp of approval on watch dials, regardless of the fact that it’s sometimes a “marketing term” as much as a quality guarantee. Rules aren’t super strict for a watch to claim itself as Swiss Made – it needs a Swiss movement (assembled and inspected in Switzerland) and must be cased in Switzerland, but only 60% of production costs must stay within Switzerland, and only 60% of the movement must have Swiss-made parts (by value). So, it’s Swiss enough, but not all Swiss-made watches are equal. Rolex watches are virtually 100% Swiss Made, as the watchmaker even has its own foundries in Switzerland to refine raw materials. Almost everything is made in-house, from design to movement manufacturing to cases and bracelets – even sapphire crystals, hairsprings and escapements are produced in-house. Jewel bearings and certain raw materials are sourced elsewhere (like unrefined platinum), but those either come from Switzerland or are metals processed by Rolex to specific alloys.

Brands like Tissot, Longines and Swatch offer Swiss Made watches that just meet the minimum standards (at least at the lower end) to keep prices affordable, contrasting with elite brands like Rolex, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Patek Philippe and many more that come close to 100%. Again, not all Swiss-made watches are equally Swiss. For a quick comparison, a “Made in the USA” watch must meet very strict guidelines from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which requires all or virtually all components, assembly and labour to be within the United States. Unfortunately, parts that are nigh impossible to produce or source domestically, like hairsprings and jewels, are sourced from Switzerland, so watchmakers like RGM stop at about 90% American-made. Very close, but arguably unable to hit the FTC standard. However, this vertically integrated watchmaker, along with J.N. Shapiro and others, are still considered true American watchmakers and would easily exceed the looser Swiss Made standards.

Switzerland is the watchmaking capital by value, but not volume. For example, the Apple Watch alone sells around 10 million more units per year than the entire Swiss watchmaking industry, but generates far less annual revenue. In 2025, the country exported approximately 14.6 million watches with a revenue of over CHF 25 billion. Most of the elite and desirable watch brands are Swiss – Rolex, the Holy Trinity of Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin and Audemars Piguet, Breguet, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Omega, IWC and so on, not to mention extremely popular mid-range players like TAG Heuer, Longines, Breitling and Tudor. Comparable brands exist elsewhere, but in far fewer numbers. Some of the most important horological innovations throughout history are also Swiss, such as the tourbillon invented in 1795 (patented in 1801) by Abraham-Louis Breguet, who also invented the Breguet overcoil (modified hairspring) around the same time to remove isochronal errors. A quick note on this – although Breguet is considered a Swiss brand given Abraham-Louis Breguet’s Swiss heritage and the current headquarters, he was based in Paris, France, during this time. Many key inventions actually occurred outside of Switzerland as well, such as the lever escapement invented by English watchmaker Thomas Mudge in the mid-18th century, and the first pocket watches (or basically portable clocks) powered by a mainspring, invented by German locksmith Peter Henlein in the 16th century.

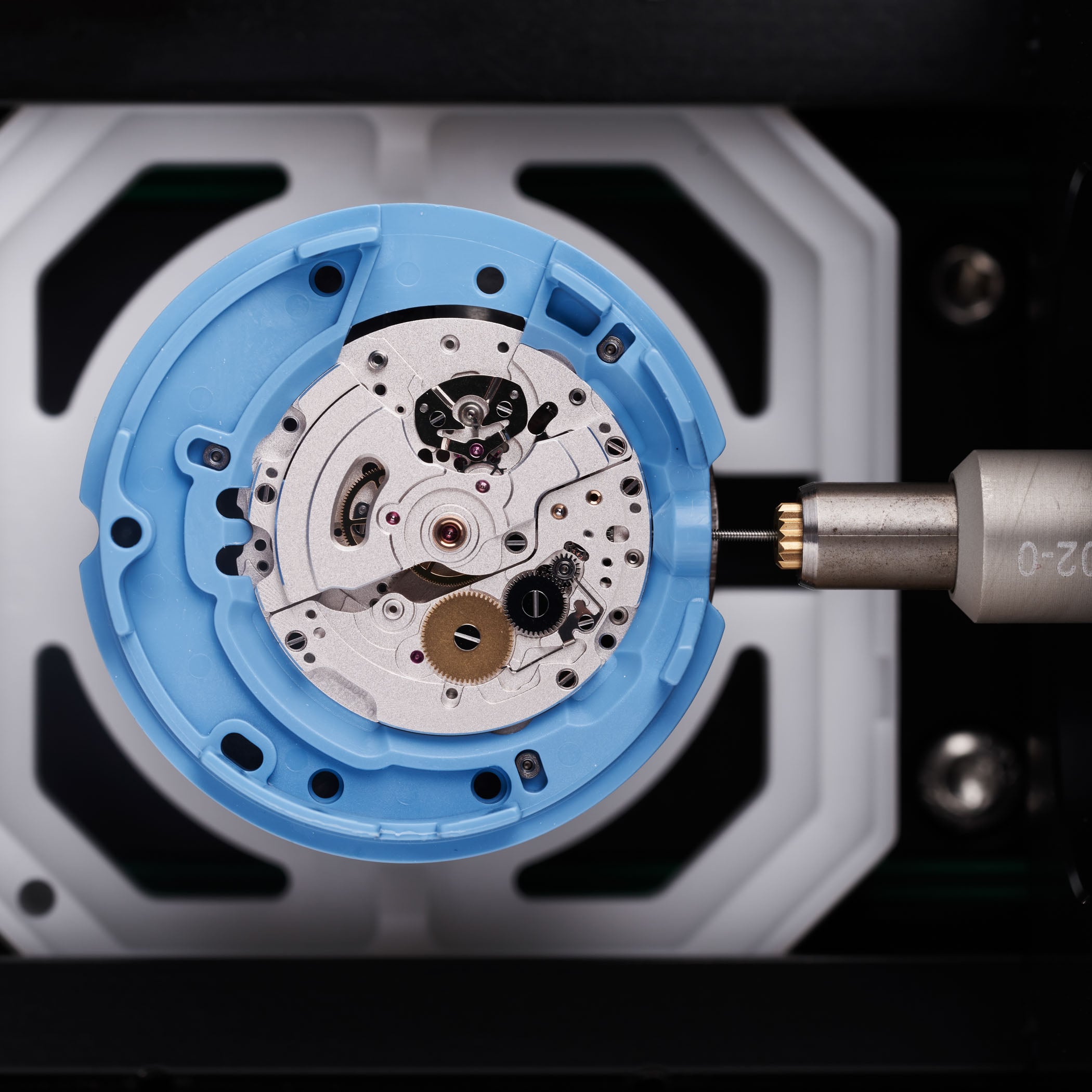

It wasn’t just key inventions, high complications and consistent quality that made Switzerland the king of horology (although all of those are very important), as a broad ecosystem of suppliers hammered things home. Difficult parts like jewel bearings, hairsprings, mainsprings, escapements, and so on overwhelmingly come from Switzerland and supply the world. Going back to American watchmaker RGM, critical parts like jewels, hairsprings, escapements and balance wheels come from Switzerland, emphasising the importance of the Swiss ecosystem for vertically integrated brands outside of the country. Movement manufacturers like ETA (the largest in Switzerland), Sellita and Soprod supply both Swiss brands and the world at large, while Nivarox-FAR and Swiss Jewel produce hairsprings and jewels, respectively. Very few independent companies outside of Switzerland manufacture such parts, so Switzerland holds a monopoly on this to a degree. The global dominance of critical parts is almost as important as Swiss watches themselves.

China

While Switzerland is the largest watchmaker by value, China is the largest by volume (and it isn’t even close). Swiss watch exports were again around 14.6 million in 2025, while Chinese exports surpassed 590 million in the same year (valued at around USD 18 billion compared to Switzerland’s USD 31 billion). China’s watch market began in earnest in the 1950s with eight state-owned brands that included the Tianjin factory (now Seagull), Beijing Watch Factory, Shanghai Watch and Peacock Watch. Hangzhou Watch Company surfaced about 20 years later and is also a Chinese powerhouse with in-house production and even high-end movements – micro-rotors, tourbillons and more. Although “Made in China” has a negative connotation to many, today’s Chinese watch market delivers reliable and often complex movements and watches at very attainable prices. Mechanical dive watches with automatic movements and 200-metre water resistance ratings sell for around USD 300, while tourbillons in Seagull’s Heritage series sell for less than USD 3,000. Stylish, time-only models can be had for less than USD 200 with easily serviceable and reliable movements. In late 2024, Seagull introduced the most accessible in-house split-second mechanical chronograph, which was also a first for Chinese watchmaking. Simply called the Split-Second Chronograph Limited (ref. 418.13.1077), it bucked the trend of the complication only residing among high-end watchmakers like the Patek Philippe 5370R or A. Lange & Söhne 1815 Rattrapante – both playing in a totally different league of finishing. It sells for only USD 3,499 when most are USD 10,000 or more.

China’s wristwatch industry started with reverse engineering as its first watch, the WuXing or Five Stars, debuted in 1955 and was based on a rather crude Swiss pin-lever movement with five jewels. It was designed by a team of four and got the Chinese watch market rolling, but the hand-wound and reliable Shanghai A581, a couple of years later, with 17 jewels, was China’s first mass-produced watch from the Shanghai Watch Factory, based on the improved Swiss AS 1187 calibre (and possibly the AS 1194). This became China’s primary domestic movement until the mid-1960s when the Shanghai Watch Factory developed the superior SS1 series, although the Chinese government soon changed course with the Ministry of Light Industry initiative, consolidating watchmakers from several brands to design a standardised movement. All factories had to cease production of their own movements (with very few exceptions) and produce the new Tongji (Unified Mechanism) calibre, modelled after the Swiss Enicar AR1010. The standardisation effort resulted in over 30 factories dedicated to producing the movement, and Chinese production went from about 6.5 million watches in the mid-1970s to 33 million in the early 1980s. The final design specified a minimum of 17 jewels, a beat rate of 21,600vph (3Hz), a power reserve of at least 40 hours and accuracy within +/-30 seconds per day. One of the main goals of the initiative was to provide reliable and accurate domestic watches that just about any Chinese worker could afford.

Following the quartz crisis and Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997, the Tongji fell out of favor and quality control was soon all over the map, although new variants developed within the last 20 years are again well designed and reliable. These are often seen in low-priced mechanical watches from brands like Invicta and Fineat. Factories resumed independence with their own watches and in-house movements, and Seagull is currently the largest domestic watchmaker. It produces the highest number of mechanical movements in the world (up to 3 million per year), supplying various watch brands globally.

Chinese High Horology

China’s watch industry isn’t strictly about high volume and low prices (although that’s a major component), as there are more advanced watches and bona fide haute horlogerie as well. A great example is CIGA Design with models like the unconventional Blue Planet Titanium that won the 2021 Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève Challenge Award (non-titanium variant). The watchmaker also has the Everest Summit Central Tourbillon that introduced an in-house tourbillon movement, calibre CD-05. Behrens is another example with pieces like the B023 and Ultra-Light 20g with a featherweight case and double-retrograde movement. Qian GuoBiao (aka the Tourbillon Doctor) brings it to another level with a split-second chronograph, double balance wheels and a 2024 collaboration with Behrens, and this indie watchmaker specialises in displaying intricate mechanics on the dial side.

Recently, Fam Al Hut also made a lot of noise (rightfully so) with its Bi-Axis Tourbillon, an ultra-compact, internally developed watch that not only has truly impactful design but also true watchmaking credentials. And we should also mention names such as Logan Kuan Rao and Qin Gan, both on the independent watchmaking scene. Last, Atelier Wen is another interesting one, known for its intricate guilloché (by Cheng Yucai) and porcelain dials. Affordable tourbillon and micro-rotor models can be found from Seagull, Hangzhou and more, significantly undercutting Swiss and European counterparts, although overall quality and finishing are generally a few steps behind at these price points.

The Chinese ecosystem

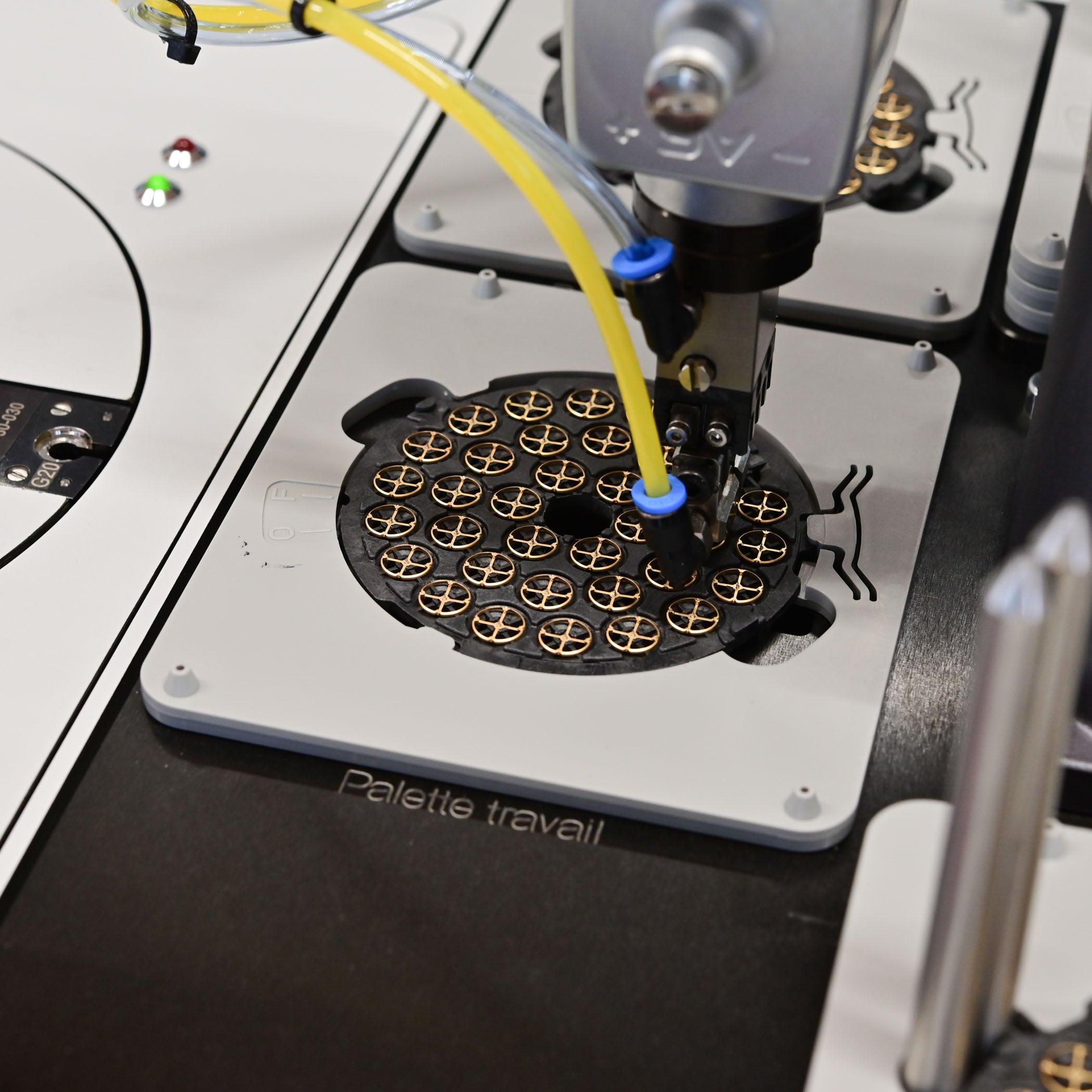

Like Switzerland, China is a major supplier of movements and parts to the watch industry. For example, Baltic’s highly praised MR01 and expanded MR Roulette collection feature a well-decorated micro-rotor movement (CAL5000a) for around EUR 600, thanks to Hangzhou Watch Company. It would be impossible to offer such a movement anywhere near that price outside of China’s industry. Seagull’s ST-19 (based on the Swiss Venus 175) is considered the “biggest bang for the buck” when it comes to a high-quality chronograph movement, providing a nicely finished package with a column wheel and horizontal clutch. It’s used domestically in the celebrated Seagull 1963 (reissues) and throughout the world by brands like Studio Underd0g and Mercer, bringing a traditionally pricey complication to the masses.

Seagull has unfortunately raised its minimum order quantity to 10,000, so many small brands will lose access to this affordable champion as the numbers are just too high for small portfolios. In addition to movements, critical parts are supplied globally in vast numbers like cases, dials, hands, sapphire crystals and bracelets, which are widely used by Swiss brands that can still meet the low(ish) 60% threshold for Swiss Made. Without these low-cost, high-quality components, many lower and mid-range Swiss watches would be significantly more expensive and possibly priced out of the market. Chinese suppliers are truly an ingrained part of Swiss watchmaking and the broader global industry.

Japan

The Japanese watch industry is unique in several ways. For starters, it’s responsible for the Quartz Crisis of the 1970s and 1980s that forever changed the industry (for better or worse), thanks to Seiko’s quartz Astron in 1969, which started it all. The four dominant brands have also proven to be incredibly innovative and adaptable, thriving during eras of major change when others struggled or collapsed completely. Japanese watches were born in the late 19th century, late compared to European counterparts, but well before China’s industry. Kintaro Hattori founded Seiko in 1881 as a repair shop until the Seikosha factory opened in 1892 for clock and ultimately pocket watch production (the Timekeeper pocket watch in 1895). The Laurel was Seiko’s (and Japan’s) first wristwatch in 1913, with production of up to 50 pieces per day, but it wasn’t until 1924 that “Seiko” branded watches first appeared. Fast forward to 1969, and the quartz Astron started a new era of cheap, hyper-accurate and innovative watches that almost destroyed the traditional mechanical watch industry (although the original Astron was priced as much as a car at the time). Today, Seiko is a vertically integrated manufacture to the peak of its definition – everything is produced in-house, from escapements and balance wheels to hairsprings, jewels and crystals, and all quartz crystals and components are also exclusively Seiko’s. The brand even makes its own lubricating oils and lume (LumiBrite). Very few watch companies can make this claim of total vertical integration. In addition, the Group also comprises two higher-end watchmakers, Grand Seiko and Credor.

Citizen is the second major Japanese watchmaker (of the Big Four), founded by Kamekichi Yamazaki in 1918 to increase domestic watch production. Early innovations include Japan’s first shock-resistant watch in 1956 (Parashock), first water-resistant watch in 1959 (Parawater) and the world’s first titanium watch case in 1970. Although Seiko invented Quartz, Citizen took that ball and ran with it, developing the most advanced light-powered quartz technology that remains unsurpassed today, Eco-Drive. Unlike early solar-powered watches that had solar cells front and centre on the dial, Eco-Drive’s cells are hidden beneath the dial for a traditional, non-techy aesthetic that completely changed the game. Seiko and others have caught up for the most part, but Eco-Drive is still the gold standard for light-powered watches. In 2019, Eco-Drive went to the next level with Calibre 0100, which was accurate to one second per year. There isn’t a mechanical watch that can achieve such accuracy on average per day. This milestone has not been matched by any company. Given all of this technology and innovation, it’s important to remember that, like Seiko, Citizen has a comprehensive mechanical portfolio and is also a massive movement manufacturer with Miyota. Citizen and Seiko are huge global suppliers of movements, together providing the largest amount to outside brands. Ironically, China is a major beneficiary as Japanese movements are often considered superior to their own counterparts at the lower end of the market.

Until last year, Casio was always a quartz brand that specialised in digital watches, starting with the Casiotron QW02 in 1974. The Edifice EFK-100 Automatic is its first mechanical watch with a Seiko NH35 automatic, likely the first of many within the Edifice collection. Some of the most iconic digital watches include Casio’s exceptionally affordable and functional F-91W from 1989 (around EUR 20 brand new today), the rugged G-Shock DW-5000C from 1983, and the CA-50 and CA-53W calculator watches from 1984 and 1988, respectively. Although Casio generally doesn’t export parts for other brands, it’s the largest digital watch exporter in the world, with the G-shock line and inexpensive casual models like the F-91W-1 standing out. In a market where prices continue to rise, just about anyone can afford a digital Casio with a stopwatch, alarm, date and screen light today. A major contributor to these affordable prices is the lightweight and durable resin cases and straps introduced with the F100 in 1977, which simplified and sped up mass production with a cheap and very easy-to-work-with material.

The last of the Big Four Japanese watchmakers is Orient, although it’s now owned by Seiko Epson Corporation since 2009. Orient continues to operate independently, but its in-house movements are produced within the Seiko Group. Founded in 1950, Orient goes back to the Yoshida Watch Shop in 1901, which expanded until ceasing operations in 1949, finding new life a year later as Tama Keiki Company. This became Orient Watch Company in 1951 after the iconic Ocean Star watch debuted, and the brand started exporting to international markets in 1955. Orient is known for accessibly priced, in-house watches with its biggest collections being the Bambino dress watches, Mako/Kamasu divers and Flight pilot’s watches. Orient Star is a premium line with better finishing (including Zaratsu polishing) and more complex designs like open heart and skeleton dials. The brand is best known for its affordable mechanical portfolio, but also carries solar quartz models and produced digital watches in the past. Orient is the smallest exporter of the Big Four Japanese watchmakers, but still a global force with high-quality mechanical watches at some of the most affordable prices in the industry.

Germany

The closest competitor to Switzerland is Germany at the high end. Watchmakers like A. Lange & Söhne, Moritz Grossmann and Glashütte Original produce some of the finest watches in the world that can go head-to-head with some of the most renowned Swiss high-end watchmakers. In addition, the mid-range players like NOMOS, Laco and Tutima not only compete with Swiss counterparts, but often surpass them. NOMOS, for example, offers accessible and well-designed watches like Longines or Oris, but all movements are in-house, with models like the Club Campus selling for less than USD 2,000. Glashütte is the watchmaking capital of Germany, with around 10 major brands, only a fraction of what can be found in Geneva or La Chaux-de-Fonds in Switzerland. Pforzheim is another German watchmaking hub, but the country is clearly on a smaller scale compared to Switzerland, Japan and China. However, very few watchmakers outside of Switzerland can compete with Glashütte’s best.

German watchmaking goes back to the 16th century and is quite literally the country that introduced the watch, well, kind of. German locksmith Peter Henlein invented Nuremberg Eggs in the early 1500s that were basically miniaturised clocks with a single hand protected by brass lids, powered by mainsprings and worn around the neck. True mechanical portable time was the precursor to proper pocket watches. Black Forest became a prime clock-making region in the 17th century and is well known for traditional, hand-crafted cuckoo clocks today. Factories from major brands like A. Lange & Söhne, Stowa and Tutima were either destroyed during World War II or dismantled by Soviet forces, so much of German watchmaking today consists of brands that were revived after the reunification of the country. Some brands like Laco and Tutima regrouped in West Germany following the war, but hardships often kept production limited or disrupted for many years.

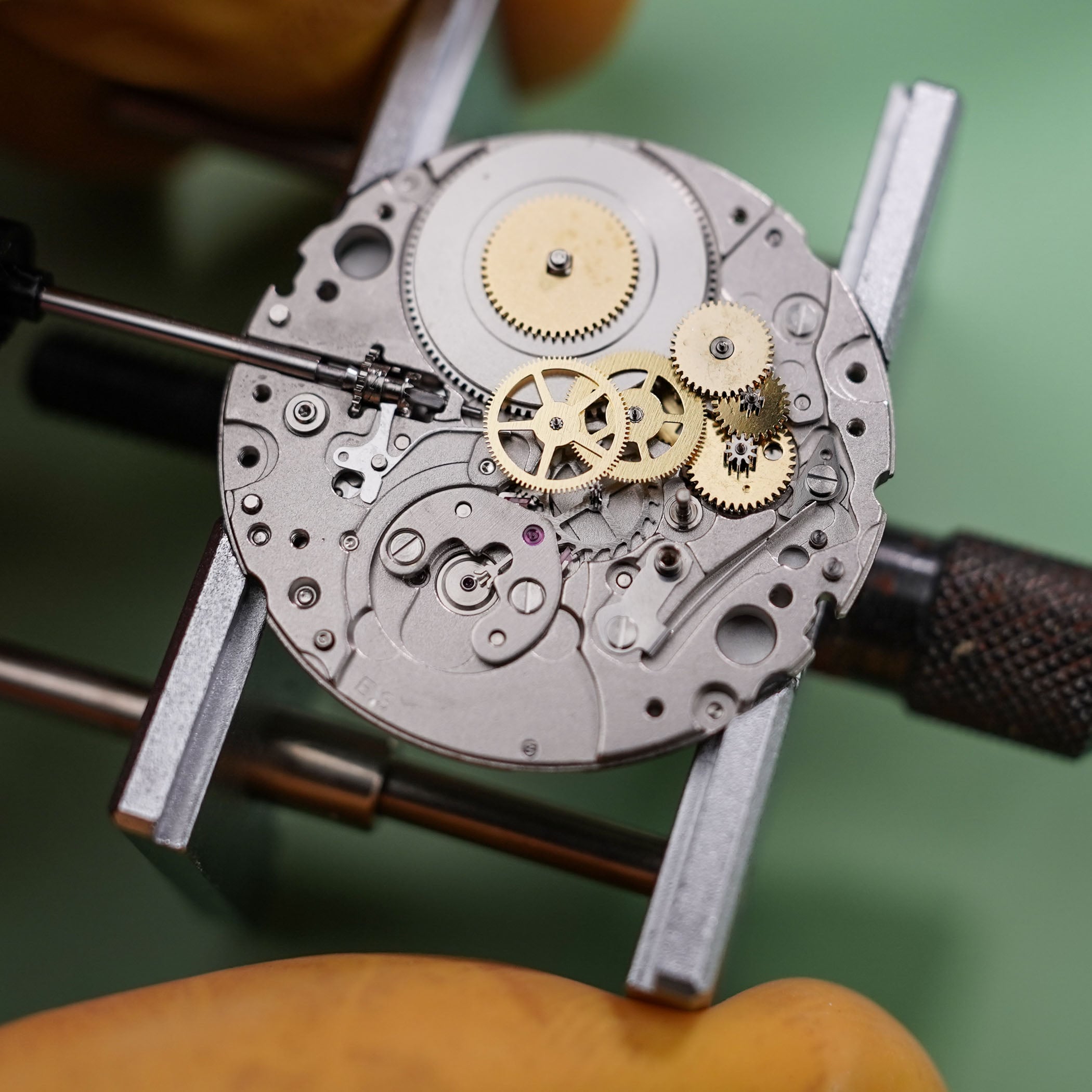

German watchmaking is known for several unique styles, such as the Bauhaus philosophy that emphasises minimalism and function. Uncluttered dials with thin indices and simple, minimal text are common – NOMOS and Junghans are great examples of this (such as Tangente and Max Bill, respectively). Three-quarter plates (covering 75% of the movement) are often used in Glashütte instead of individual bridges, providing better rigidity as it holds the barrel and entire gear train. The disadvantages include less visible movement components from the case back (although most three-quarter plates are well decorated) and increased difficulty in servicing. German silver is a popular alternative to more common metals in German movements and replaced actual silver that was prone to tarnishing. German silver is an alloy of copper, nickel, and zinc, and has a desirable silver sheen that can pick up a subtle warm patina over time. It’s more durable than traditional brass and usually left untreated (no plating) on movements and even dials, and has become a popular albeit somewhat rare watchmaking material in other countries. And here’s a fun fact – while Breguet invented the tourbillon, the more advanced and aesthetically pleasing flying tourbillon was invented in 1920 by Alfred Helwig in Glashütte.

France

French watchmaking is lesser known than the above countries today, but still a major (and growing) contributor to the industry with a long and illustrious history. Cartier is the best-known, high-end watchmaker in France, but Hermès, Bell & Ross, Pequignet and Yema are also French. That said, Cartier, Hermès and Bell & Ross watches are Swiss-made despite having French headquarters and design studios. Mid-range players include Baltic and Charlie Paris, but they also don’t use French movements. Are you seeing a pattern? France is known for design today (the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode organises Paris Fashion Week every year), but not so much in-house horology. Much of the heavy lifting still happens in neighbouring Switzerland with Japanese and Chinese help, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t in-house French movements. Pequignet makes high-end, in-house calibres like the Calibre Royal (automatic or hand-wound), Calibre Royal tourbillon and more accessible Calibre Initial automatic. Yema has impressive in-house movements that include the CMM.10 automatic, CMM.20 micro-rotor and CMM.30 tourbillon calibres. Both brands represent true French horology today with iconic collections like Yema’s Superman and Pequignet’s high-end Royale Paris. With a watchmaking history going back centuries, why aren’t there more in-house French watchmakers? The Quartz Crisis is largely to blame, along with a close (and convenient) proximity to Switzerland. Morteau in France (home to Yema and the prestigious Lycée Edgar Faure watchmaking school) is only 30 minutes from La Chaux-de-Fonds in Switzerland.

French Watchmaking History

In the 15th century, French clock making centered around Paris and the Jura region. The Gros-Horloge (Great Clock) is among the oldest of French clock towers in Rouen, Normandy, going back to 1389. In the 18th century, Paris became a horological epicentre with some of history’s best watchmakers working there, from Abraham-Louis Breguet to Ferdinand Berthoud to Jean-Antoine Lépine. An observatory for certifying chronometers was established in Besançon in 1867, reinforcing France’s commitment to high precision. Following a strong start in the 20th century, the Quartz Crisis devastated French watchmaking, and only a handful of brands like Yema survived, although it was owned by several companies, including Seiko, before truly rebounding in 2009. It was acquired by French group Montres Ambre, which moved its headquarters back to Morteau, and in-house development and production resumed. Pequignet also suffered from the Quartz Crisis, although it was founded in 1973 during the start of the Japanese surge. It was bought in 2004 and developed the high-end Calibre Royal movement, but couldn’t remain solvent and entered receivership. By 2013, new investments helped the watchmaker continue with Calibre Royal movements, and Pequignet represents French haute horlogerie today.

A Global Industry

This certainly isn’t a comprehensive list of watchmaking countries, but it does list five major and historical ones. The United States has a celebrated horological history in the 19th and 20th centuries with Hamilton, Waltham, Elgin, Bulova and Timex. A handful of haute horlogerie watchmakers like RGM Watch Company and J.N. Shapiro continue the American tradition today, but those watches come with high prices and limited production. More accessible American brands aren’t vertically integrated. Italy has many brands that use Swiss or Asian movements, but OISA 1937 (founded in 1937 in Milan) produces the in-house, hand-wound Calibre 29-50 Cinque Ponti (Five Bridges) for LOCMAN Italy watches. OISA 1937 was shuttered during the Quartz Crisis in 1978, but revived by the founder’s grandson in 2017. It’s great to see mechanical watchmaking thriving today after the Quartz Crisis and subsequent turbulent decades, and in-house production should only expand in smaller watchmaking countries as consumer demand continues to grow.

9 responses

The UK has a rich history as well well as a xurrently significant presence in watchmaking at various levels of price tiers, watchmaking, production and manufacturing capability, as well as one of the most celebrated legacies in modern watchmaking in the late George Daniels and currently Roger Smith. Personally, I would have given the UK the final spot over France, at least at this time.

Another terrific article from you. Both educational and enjoyable to read. Good stuff here. I’d rather learn about these kinds of things than having to put up with another watch review whose brand is looking for approval in justifying charging outrageous prices for something that deserves less.

@JFizzles The UK was close, along with the US, but France has the edge with its current brands and history (but it was close for sure and a bit of a toss up). And let’s not forget Christopher Ward and its amazing achievements in the mid-range market.

This is a lot of wonderful information thoughtfully presented in a single article. I would posit that India may deserve a place on the list. HMT was a domestic brand that produced manual wound, automatic, analog -digital and quartz movements all in-house. It ended up manufacturing tens of millions of pieces over its five decades existence. Additionally India is home to Titan which currently produces a razor thin quartz movement and has recently launched its own tourbillion along with an ultra thin manual mechanical movement.

French watchmaking LOL what about British?

extremely educational & fun to read article, as mentioned by others I would have at least mentioned the UK in this article.

When it comes to design, and not just matchmaking skill, France really has the edge over the UK historically.

British watchmaking is absolutely snubbed here! Really deserves more credit from historic and modern aspect.

Didn’t mention Sinn!