The Difference Between Mechanical and Quartz Watches

Back to basics with our new educational series, designed to teach everything there’s to know about watches.

Editor’s note – As our long-time readers might know, MONOCRHOME is usually quite (to say the least) technical. We like to go in-depth, to look at the ins and outs of watchmaking, sometimes tackling highly complex topics. This was the main objective behind our “Technical Perspective” series, where we’ve covered some of the most complex aspects of a mechanical watch. Yet, we must keep in mind that not all our readers are seasoned collectors and long-term watch enthusiasts. With this new series of articles named “The ABCs of Time”, we intend to bring the basics to newcomers in the world of watches, to make learning about watches and watchmaking as simple as possible, by going back to the basics.

It’s not uncommon for different technologies to mimic each other and ultimately provide the same experience. For example, an older plasma TV is very different from an LCD TV, and both differ from an OLED TV, but the experience for viewers is largely identical. And don’t forget about cathode ray tubes. You can say the same thing about watches with the quartz vs. mechanical debate. On analogue dials, they look nigh identical and relay time in the same way, while complications like dates and calendars, chronographs and so on just about operate identically (from a visual standpoint). The technology that drives them, however, is very different, and although they live harmoniously side by side today, that wasn’t always the case. Let’s open up the ABCs of Time series by looking at the difference between mechanical and quartz watches.

Mechanical Predates Quartz by Centuries

Mechanical timekeeping dates back to the late 13th century, with European clock towers that used a primitive escapement and gears with hanging weights to measure time; bells would signal the hours, as dials and hands were yet to be used. This established the three pillars of mechanical timekeeping: a power source (weights, in this case), a regulator (known as the balance wheel today), and an escapement that works in tandem with the regulator to provide fixed impulses to advance the time in a controlled manner.

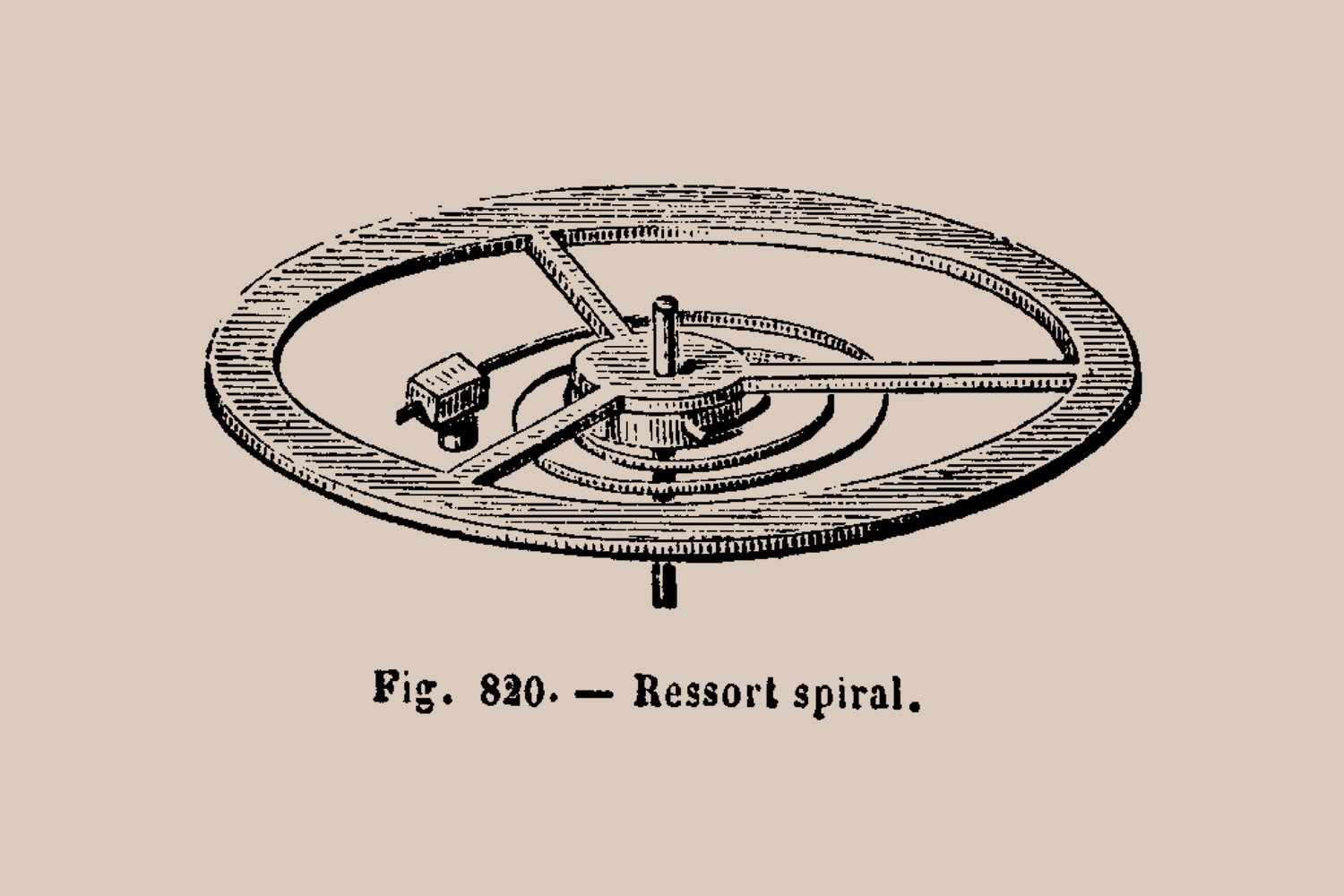

Fast forward to the 15th century, when internal mainsprings began replacing weights, enabling smaller, portable clocks that soon gave rise to wearable timepieces. Early “pocket watches” were small, spring-driven clocks that were worn around the neck, but they had a dial and an hour hand that marched us closer to modern watches. The balance spring invented by Christiaan Huygens in 1675 and the lever escapement invented by Thomas Mudge around 1755 were game changers, allowing for slim, accurate and contemporary pocket watches as we know them today. A handful of improved escapement designs came before, but they were all a bit experimental by today’s standards. The lever escapement design has been perfected and is still used in the majority of modern watch movements.

How Does a Mechanical Watch Movement Work?

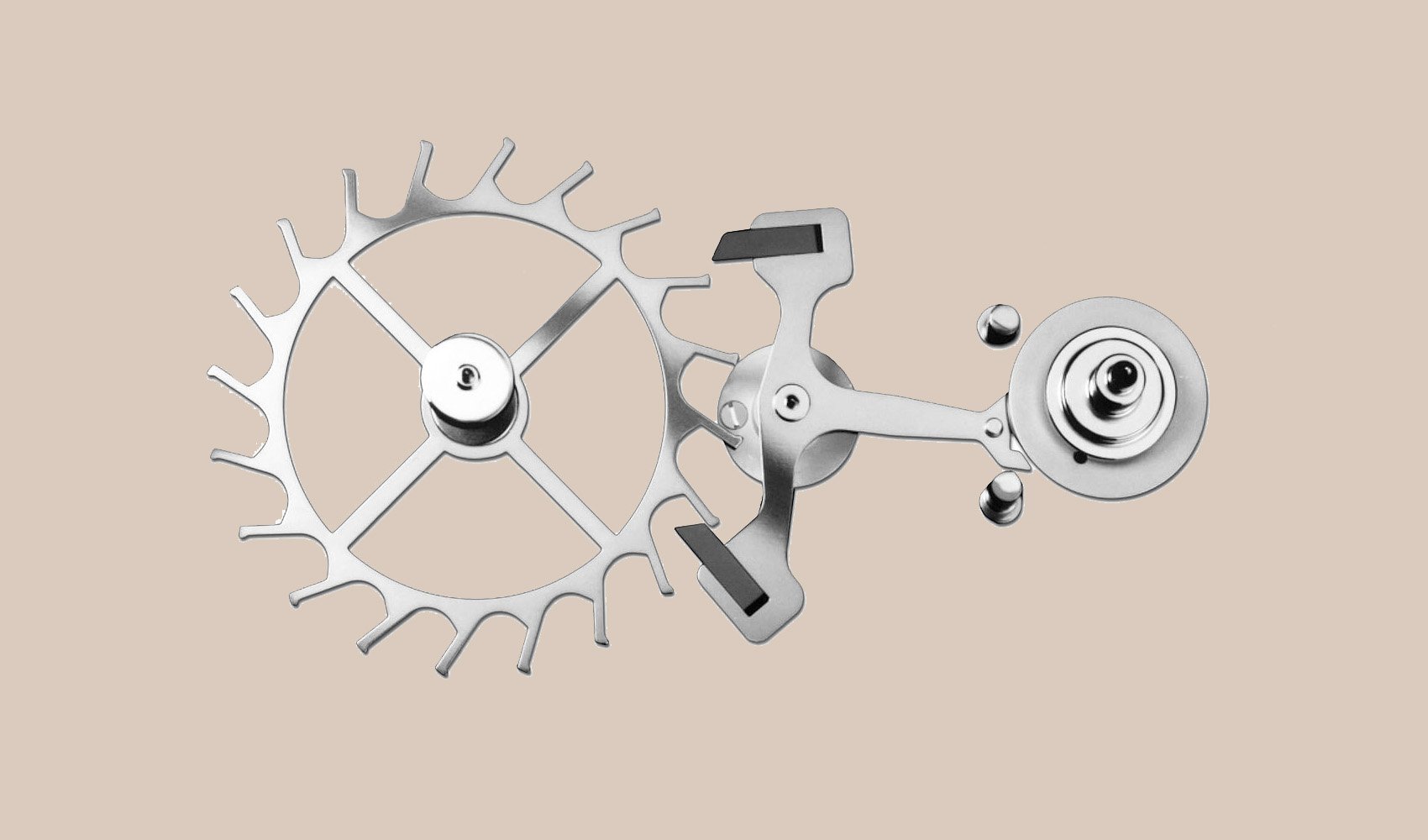

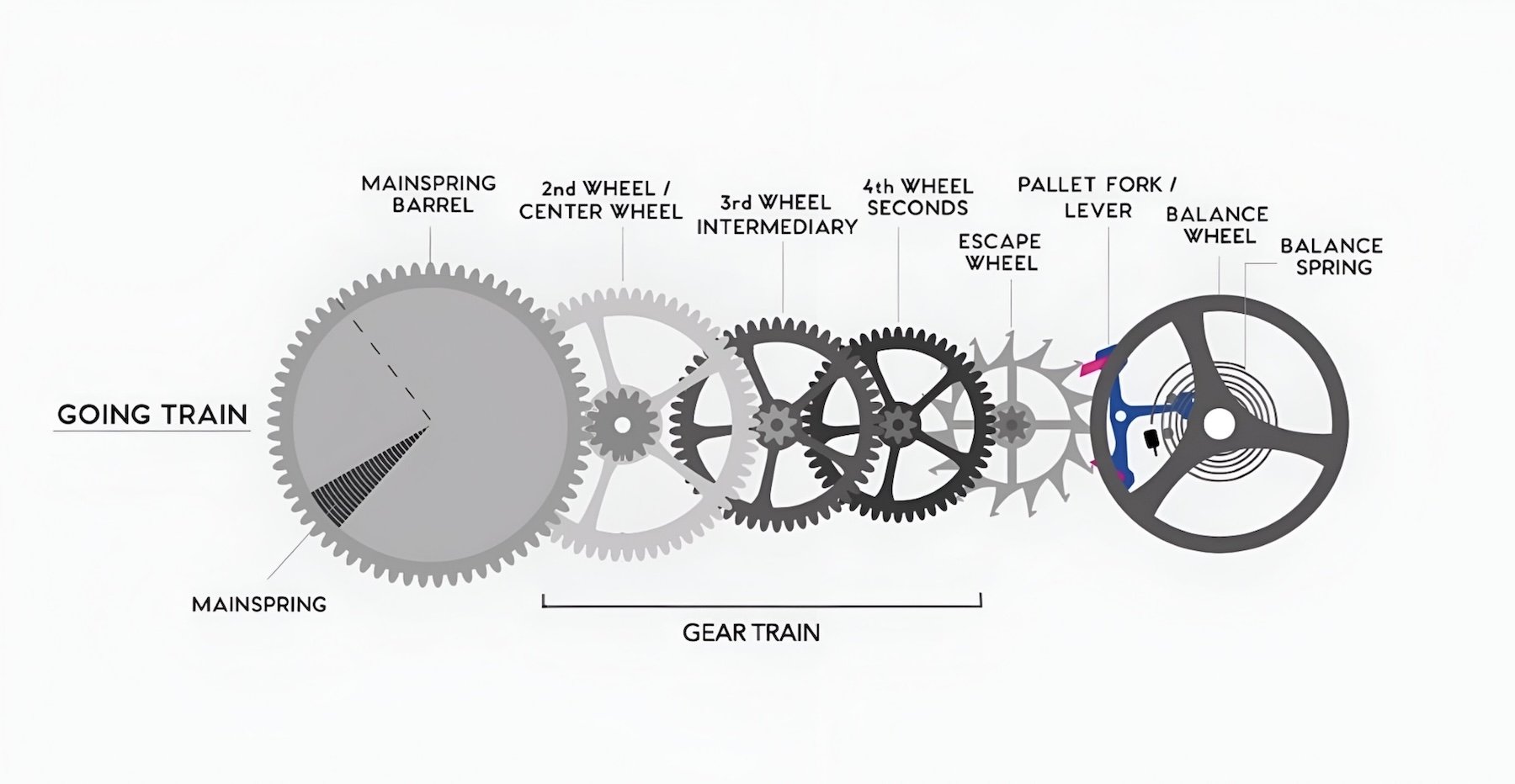

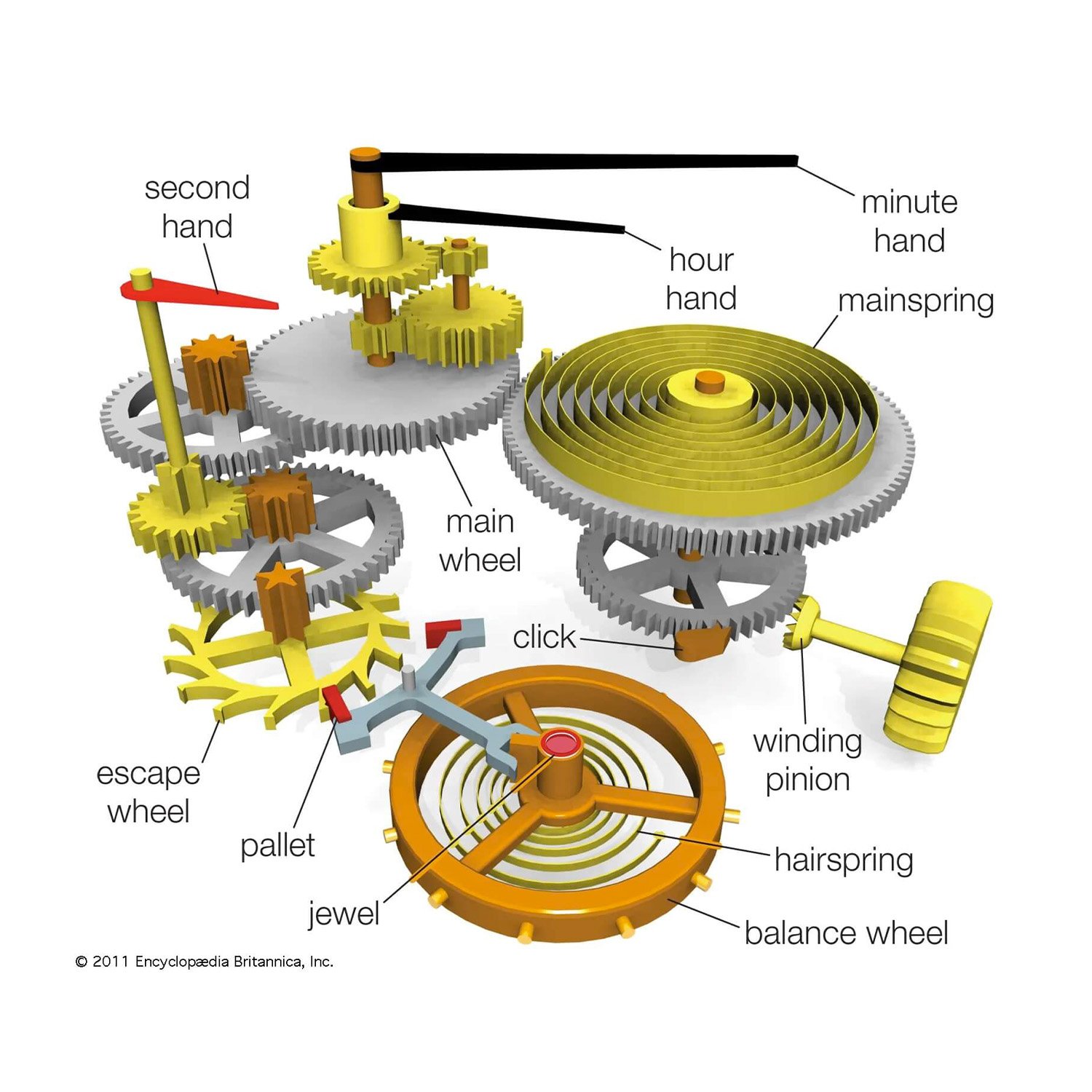

A modern mechanical watch starts with a power source independent of electricity (no batteries involved). A coiled mainspring contained in a barrel powers the watch. It can be wound with the crown, usually located at 3 o’clock, which also sets the time, or via a weighted rotor at the back of automatic movements that spins by natural wrist movement. A series of gears, known as the gear train, transfers the energy of the unwinding mainspring to the escapement and balance. The latter two manage the release of this energy with controlled, back-and-forth impulses from an escape wheel gear engaging with a pallet fork – the tick-tock of a watch.

Without the escapement, regulated by the oscillating balance wheel with its own hairspring, the mainspring would quickly unwind like a spring-driven walking toy. Along the gear train are several gears and arbours that act as the “watch transmission”, and although not generally interchangeable, most time-only watch movements have common layouts. Some gears rotate the hands directly, such as the second gear (or second wheel, as it’s known), which rotates once per hour and is attached to the minute hand. The second wheel also rotates the hour hand via a 12:1 reduction gear system called the motion work (making it rotate once every 12 hours). The fourth wheel rotates once per minute, so it’s attached to the seconds hand. This is simplifying things, but that’s the gist of it for a standard three-hand dial.

Complications and Modules

Once complications (any additional functions beyond the standard hours, minutes, and seconds) or unconventional displays come into play, such as calendars, chronographs, wandering hours, and so on, separate modules with their own gear trains are often “plugged into” the base movement for the additional functionality. Dubois-Dépraz in Switzerland is a major module supplier and specialises in perpetual calendars and chronographs. Some watchmakers handle modules themselves in-house, while other movements integrate the complications and don’t require separate modules.

About Quartz Watches

There’s an era known as the Quartz Crisis in the 1970s and 1980s, when inexpensive, exceptionally accurate and trouble-free Japanese electric watches took the industry by storm, permanently decimating many traditional watchmakers and severely threatening many others. You never had to wind quartz watches; they were more accurate per month than mechanical watches were per day, and mass production was significantly cheaper and easier. Many feared that mechanical watchmaking would go the way of Blockbuster and Tower Records following the rise of online streaming (so to speak, as that wasn’t a thing yet), but tradition ultimately endured, and mechanical watchmaking is again thriving. Both quartz and mechanical watches live side-by-side on store shelves today, and many companies offer both types within their portfolios, so they certainly don’t compete with each other like they once did.

Electric Watches Before Quartz

Quartz watches weren’t the first to be battery-powered; that honour goes to Hamilton’s Ventura from 1957. This was more of a hybrid since the mechanical mainspring was replaced with an electronic equivalent, but the mechanical balance and escapement remained. It was basically a mechanical watch that you didn’t have to wind, which certainly sounds cool, but it was problematic.

The watch itself had a radical design, with an asymmetrical, triangular shield-shaped case and a futuristic dial featuring an electrical wave pattern in the centre and applied round indices with extending lines, giving off an atomic-age vibe. Elvis Presley himself wore one in the 1961 movie Blue Hawaii, which helped keep it at the forefront of popularity, but technical issues ultimately doomed the model. The original calibre, Model 500, was replaced with Model 500A and then Model 505, but battery drain, inaccuracy and reliability issues persisted, and many required premature servicing. That said, it was an innovative and pioneering effort by Hamilton and a real glimpse at the future.

In 1960, Bulova introduced the Accutron, which was the first all-electric watch. The mechanical timing elements from the Ventura were replaced with a high-vibrating, 360Hz steel alloy tuning fork that hummed instead of ticking, powered by an electronic oscillator. Accutron’s calibre 214 had only 12 moving parts and an accuracy of 2 seconds per day, which rivals that of the most accurate mechanical watches today. The name Accutron came from “Accuracy through Electronic” and this technology was heavily utilised by NASA’s early space programme. We all know that Buzz Aldrin wore an Omega Speedmaster on the Moon, but he also had an Accutron timer inside the lunar lander.

Other electric watch efforts came and went in the 1960s, but like Beta vs. VHS, it was quartz technology that ultimately won the electric watch battle. Even before Hamilton’s Ventura, brands like Elgin had electric watch prototypes as early as 1952, but none were ready for a commercial release.

1969 Seiko Astron – The First Quartz Wristwatch

The industry changed forever when Seiko introduced the world’s first quartz watch in Tokyo, which was 100 times more accurate than a mechanical counterpart. It was initially priced as much as a small car, as cutting-edge technology (at the time), and a gold case came at a cost, but quartz technology was soon easy and inexpensive to mass produce and world adoption was rapid. Seiko’s quartz technology actually debuted years earlier as a demonstration in 1963 with the Crystal Chronometer, a table clock used during the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. A battery in the Astron vibrated a quartz crystal shaped like a tuning fork, which differed from the miniature tuning fork of the Accutron, which was made of a steel alloy known as Elinvar. The advantage of quartz was its incredible stability and consistency, vibrating at a constant 32,768Hz, while a steel counterpart wasn’t as precise and susceptible to temperature fluctuations and shocks. Quartz crystals also consumed less power from the tiny watch batteries.

How Does a Quartz Watch Movement Work?

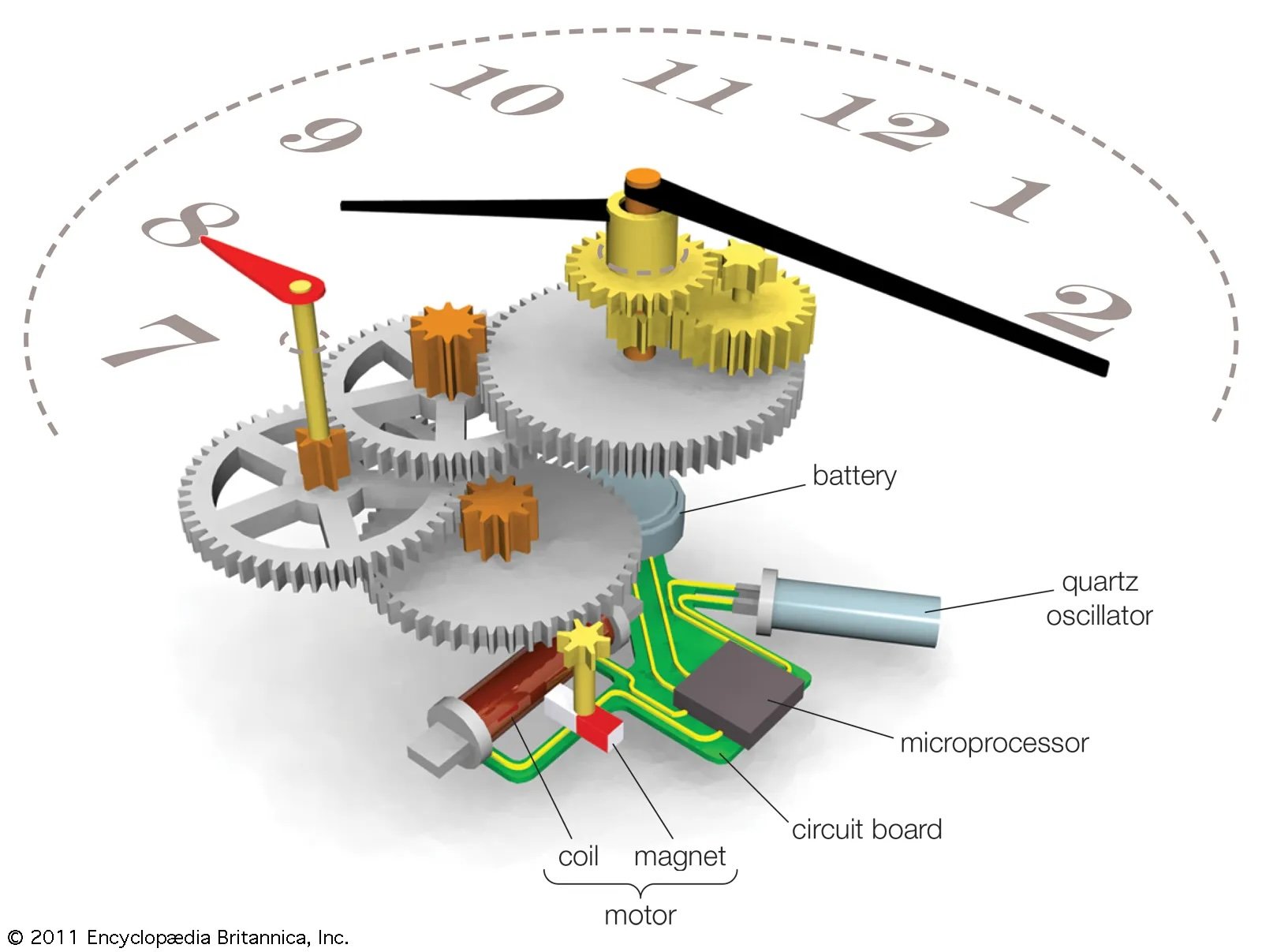

If you have a consistent motion, such as the precise back-and-forth swing of a balance wheel, you can translate that into accurate time measurements. The faster the frequency (4Hz in most “fast” mechanical watches), the more accurate a watch can be. With a quartz movement, a quartz crystal, again shaped like a tuning fork, vibrates at an incredible yet extremely consistent frequency of 32,768Hz (vs 4Hz) after the battery sends an electrical current through the quartz crystal.

You can see why quartz movements are much more accurate than the best mechanical counterparts. In fact, mechanical calibres from Rolex are certified accurate to +/-2 seconds per day, while the best quartz watch from Citizen, calibre 0100, is accurate to one second per year. From a technical standpoint, it’s not even competitive.

An integrated circuit tracks the tuning fork’s vibrations and converts them to a much slower frequency suitable for timekeeping, usually one electrical pulse per second, driving an electric motor to operate the gear train. This is evident by the seconds hand that ticks once per second instead of a smooth mechanical sweep. Quartz watches can also utilise an LCD digital display, where a microchip sends information to a screen instead of a motor driving physical hands. The same quartz technology works behind the scenes, but a screen allows for a more direct display of the time. This is also an inexpensive way to have advanced complications like a chronograph, calendar, alarm, and so on, providing tremendous functionality at a relatively nominal cost compared to mechanical movements that could cost thousands of dollars. Digital displays also enabled innovations like calculators, arcade-style games, memory banks and more, that are well beyond the capabilities of a mechanical watch.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Quartz watches have many advantages, from significantly lower prices to vastly superior accuracy, virtually no maintenance and a smorgasbord of additional digital complications at a nominal price. Traditional complications are also widespread on analogue quartz dials and are usually less expensive than mechanical options. An old quartz disadvantage was the need to replace a battery every year, early on, and, today, generally every five years, but advanced solar technology like Citizen’s Eco Drive has solved the issue. Many high-end brands continue to embrace quartz movements, including Omega, Breitling, TAG Heuer, Cartier, and Rolex, which had several quartz models in the not-so-distant past. So, why would anyone choose a watch that isn’t quartz?

Well, there’s one thing missing from quartz watches – the romance of it all. Mechanical watches have centuries of history, and these small autonomous marvels never need a battery. You wind it, you interact with it, you hear it beat. The art of a mechanical movement, especially one that’s hand-decorated, can’t be matched by the more sterile commodity that is quartz. You can drive a sedan to get from A to B, or you can drive an exotic sports car that ultimately does the same thing, but with much more emotional appeal. Watch enthusiasts, collectors, and traditionalists usually demand a mechanical watch for its “soul and heartbeat”. Logic and practicality don’t always apply in the watch game; sometimes you just have to follow your heart.

6 responses

‘the romance of it all’ .. this is absolutely hilarious!!

Quartz watches are simply better at being watches than mechanical ones.

And paying a $6-10k premium for a watch that’s identical in every way other than the choice of movement seems hardly ‘romantic’ to me lol; I’m sure can you think of a better adjective?? ?

@Esoterix given the definition of romantic being “of, characterized by, or suggestive of an idealized view of reality.” that sounds like a great choice of adjective to me.

Thanks for the great article 😀

The car analogy needs to stop.

The sports car offers a vastly different user experience than the sedan, but the mechanical watch DOES NOT offer a vastly different experience than a quartz timepiece. Sweeping second hand and daily rate anxiety is all you get.

And please, quit lecturing us about craftsmanship, every watch under 5 figures is manufactured entirely by machines wether it’s mechanical or quartz.

Romance and sports cars aside, I simply like the idea of a miniature precision machine on my wrist, even if a Miyota movement is less high-brow than some hand-made luxury alternatives. And despite the “$6-10K premium” mentioned earlier, my automatic mechanical watches all cost *significantly* less than $1K. I’m not opposed to a quartz watch—I have a quartz Ventura reissue for historical and design reasons—but the fact that I don’t find them to be as interesting doesn’t need to be a battle cry. Sharing opinions should be interesting, not threatening, no?

Excellent article I really appreciated how you explained the core technical differences how mechanical watches rely on mainsprings and gears, while quartz watches run on a lithium battery and a vibrating crystal. It’s clear now why quartz models tend to be more affordable and accurate, while mechanical ones appeal to collectors for craftsmanship and heritage. Thanks for breaking down these movements in such an understandable way

Accuracy can have different measurements and criteria. What I desire is month to month accuracy, ie, what time do I have after 30 days. My mechanical watch, inexpensive compared to today’s prices, will be within 6 seconds of NIST time whereas my Casio will be +20 seconds, accumulating every 30 days. I prefer the mechanical as I can regulate it by its resting orientation at night. Some months are 2

Seconds off other months could be 6 seconds, and I’ve

Done this for more than 6 conservatives months.