Speaking to Bernard Van Ormelingen and Bernard Braboretz, the Watchmaking Duo Behind L’Atelier Bernard

Making their debut with The Owl, Les Bernards bring a lot of good things to the table.

Although some might argue it has never lost its touch, it must be said that the independent watchmaking scene feels rejuvenated and stronger than ever. Just a couple of years ago, creative souls looking to make a name for themselves struggled to find traction and lure collectors to make their dream come true. Established names survived, with some even thriving, but it’s been an uphill battle for some of them, too. As time has moved on, so have collectors, it seems. New brands find traction almost instantly, and often it’s very much deserved, as there are some truly incredible watches being made! Take L’Atelier Bernard, for instance, and its debut model, The Owl. Named by collectors for its striking looks, it’s a fascinating piece from both an aesthetic and mechanical perspective—all the more reason to chat to the founding duo, Bernard van Ormelingen and Bernard Braboretz.

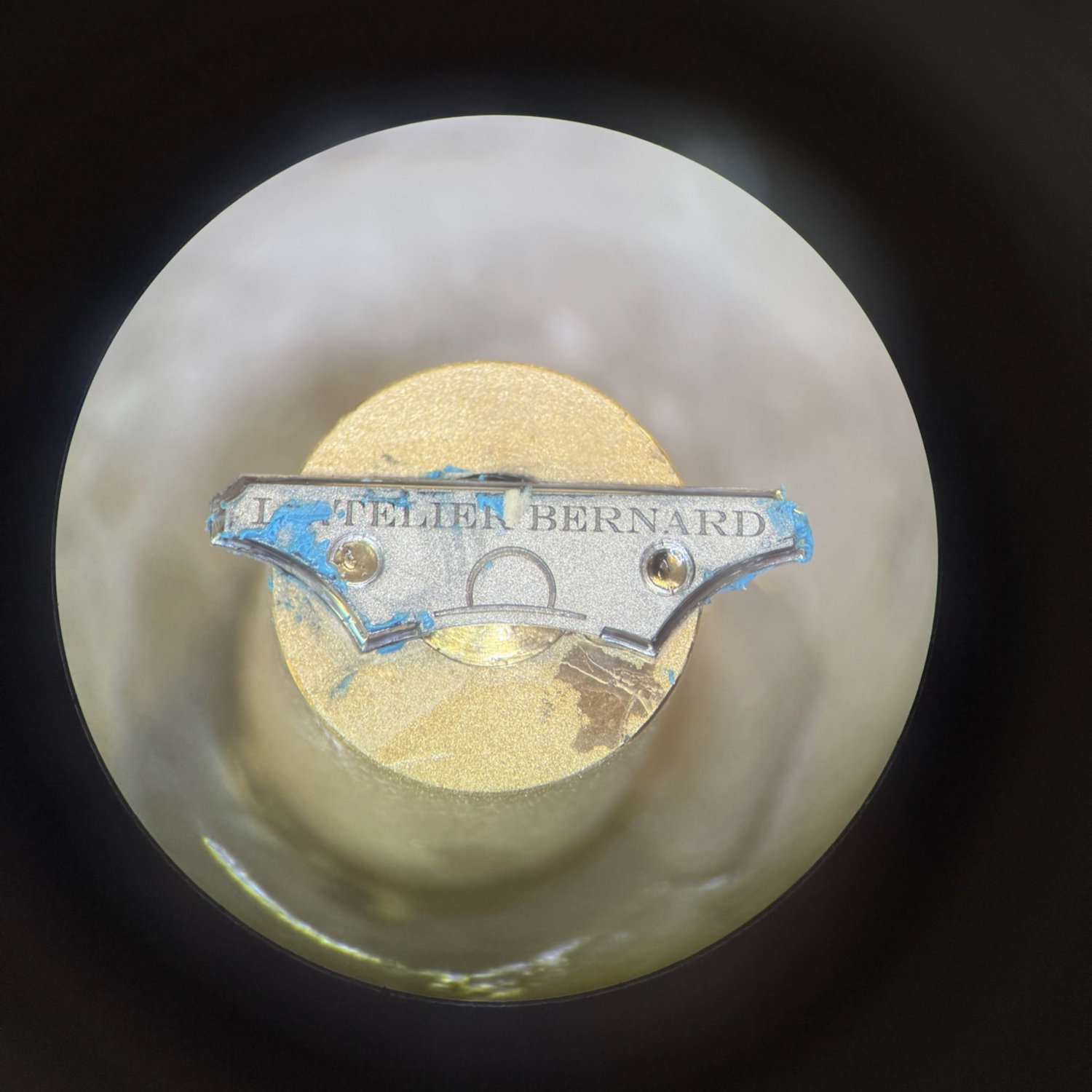

L’Atelier Bernard might be a young name, but it has been years in the making. It is the result of a long, very deliberate journey by two Belgian artisans who found a shared passion. Bernard van Ormelingen and Bernard Braboretz have spent years at the bench despite since their mid-20s. They’d been learning traditional watchmaking through practice, mistakes and repetition and working on multiple projects before thinking of signing a watch with their own name. The name Bernard van Ormelingen might sound familiar to some, for instance, as he was involved with Van Bricht a couple of years ago, making the guilloché dial for the Old Mind Tourbillon. Now, after finding a mutual connection and about three years of development, Bernard and Bernard have unveiled The Owl, and it is more than a bit fascinating!

Robin, MONOCHROME Watches – Bernard, Bernard, can you tell us how you met and decided to start your own atelier?

Our meeting was less a coincidence than a convergence. We shared the same respect for craftsmanship, the same fascination with historical timekeepers and the same refusal to separate mechanics from aesthetics. L’Atelier Bernard is not conceived as a brand in the commercial sense, but as a signature of our shared expression. Two craftsmen united by a single vision and a shared responsibility for each component of the watch.

I (Bernard Braboretz) am deeply focused on mechanics and fabrication, movement architecture, milling, turning, prototyping and adjusting, all that sort of stuff. While Bernard (Van Ormelingen) is dedicated to the aesthetic disciplines like hand-applied guilloché, concave bevelling, polishing and gold inlay, a special finishing technique he learned while working with master engraver Alain Lovenberg in Belgium (more on that later).

Shortly after we met, we realised that we share the same ideas and conceptions, but also have a complementary set of tools. Things that one of us needed, the other one had. We’re both from Belgium, so there’s a natural connection there too. We first met some time after a watch event in Belgium, and from then on we started sharing ideas and developing projects on paper. It didn’t take long for us to start prototyping what would evolve into The Owl.

Before we dive deeper into your work and the watch itself, where does your passion for watches come from?

Our passion was born from studying historical watches, especially pocket watches from the 18th and 19th centuries. Very early on, we were struck by the level of mastery achieved at a time when there were no computers, no CNC machines, no simulation software, only the hand, the eye, and time. These watches were not only precise instruments; they were complete objects of thought. Every surface was considered, every component finished, even those hidden from view. Not because it was necessary, but because it was meaningful. This approach deeply shaped our own philosophy. We did not want to make watches that simply perform well, but rather watches that testify to a way of thinking in which time is shaped patiently and craftsmanship leaves a visible trace.

How did you guys go from Belgium to Switzerland?

To us, Switzerland is the natural environment for high watchmaking, not only for its infrastructure but also for its culture of rigour and accountability. It really is the heart of the industry, even though there is amazing work done in other countries, too. Working here confronted us with very high standards of precision, reliability and finishing, standards that cannot be negotiated and that push us to do better every day. We found a place in Fleurier, right in between Kari Voutilainen and Ferdinand Berthoud, so that’s already quite inspirational to us. At the same time, our Belgian origins perhaps gave us a certain freedom of perspective. We never felt the need to follow trends or established codes.

How did L’Atelier Bernard come about?

As mentioned, L’Atelier Bernard was born from a shared conviction that watchmaking should once again be treated as a complete art form. The name came naturally, of course, as we are two Bernards seeking to establish our own atelier. Working side by side, sharing the same bench culture and the same responsibilities from start to finish, yet with our own specialities.

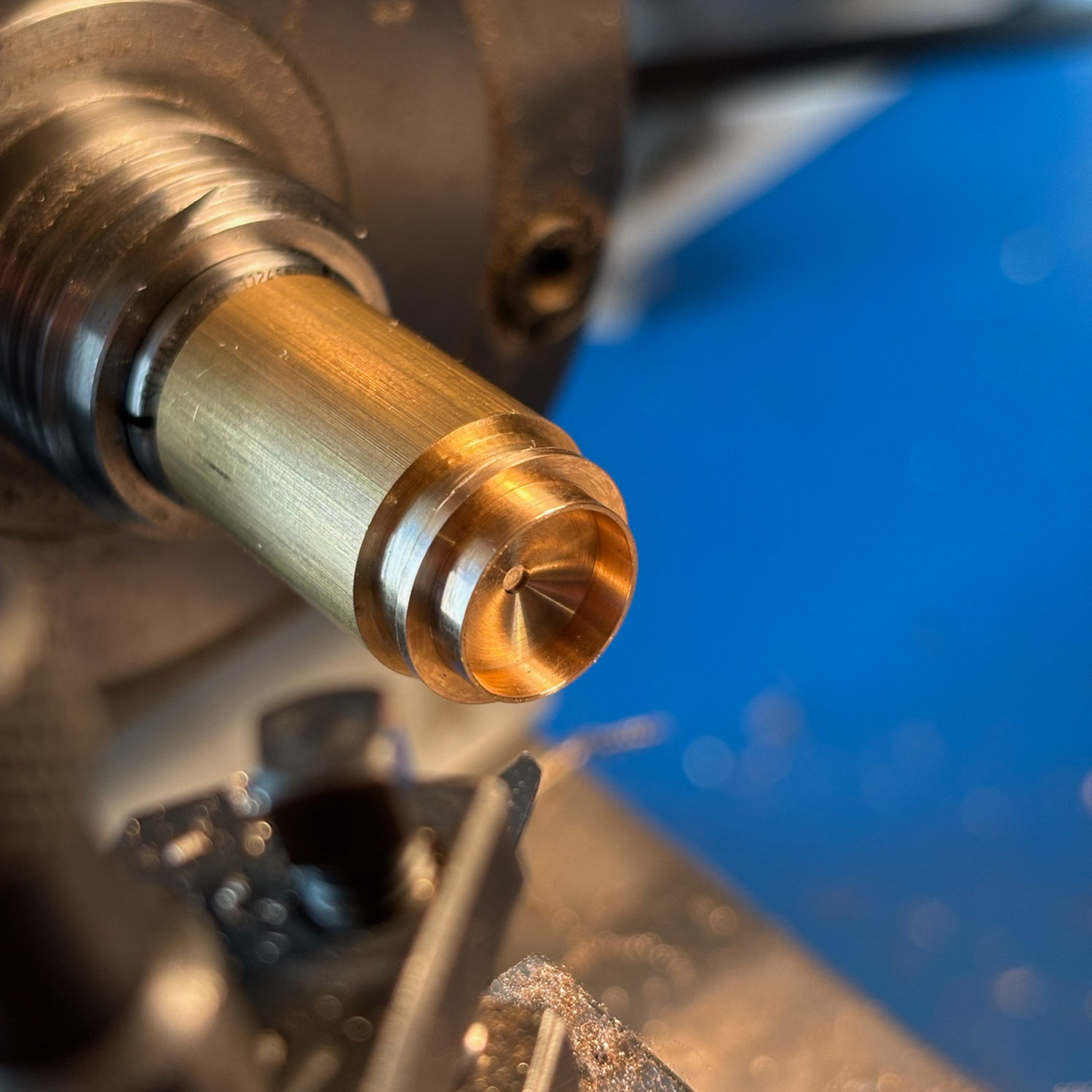

From the beginning, we decided that every watch would be developed and finished entirely by us, with no compromise on quality, construction or aesthetics. From the first sketches to the final regulation of the balance wheel, it would all be done by the two of us. No concessions, no delegations of essential savoir-faire to machines, and no multiplication of suppliers. The only elements in the movement, for instance, that are not made by us are the mainspring, hairspring and the jewels. Everything else is of our own making. Only six watches, made slowly, with discipline and absolute care, rigor and full personal responsibility at every single stage.

Your first watch is called The Owl. What’s the idea behind it?

The Owl was conceived as a statement, showcasing what we can do and how we approach artisanal watchmaking. We felt that our first watch had to express our values clearly and without compromise. Mechanical sincerity, visual coherence and a deep respect for time as something more than a unit of measurement.

We genuinely feel it is a symbol of patience, wisdom and silent observation, created over several years of our work leading up to it. Like traditional watchmaking, it reveals itself slowly; there is no easy way to do things. This is not a watch designed to impress at first glance, but one that rewards attention, understanding and time spent with it. The more you look at and interact with it, the more details will unfold, step by step.

The name comes from collectors who, when shown during development and early stages, said it looked like an owl. We loved it because the owl is often associated with wisdom and vigilance, and is often depicted as divine. An owl also has a bit of mystique to it, so it’s a perfect fit for us.

The design is rather striking, with quite a contemporary-shaped case. Can you tell us more about the design of The Owl?

We designed the case to showcase as much of the movement as possible, making it a frame for the mechanics rather than an independent object. The sloping bezel softens the overall profile and allows light to flow over the box-shaped sapphire crystal and into the case, into the movement. The crown at noon reinforces symmetry and reduces lateral stress on the movement when worn or wound.

This configuration also subtly echoes historical pocket watches and scientific instruments, where clarity and balance were always prioritised. Every decision was guided by equilibrium, if you will, from the visual aspect, but also down to the mechanical side of things and ergonomics. A watch has to look good, spell-binding even, and obviously wear comfortably and tell time. One can’t fall short of the other, or it will not be embraced by its owner.

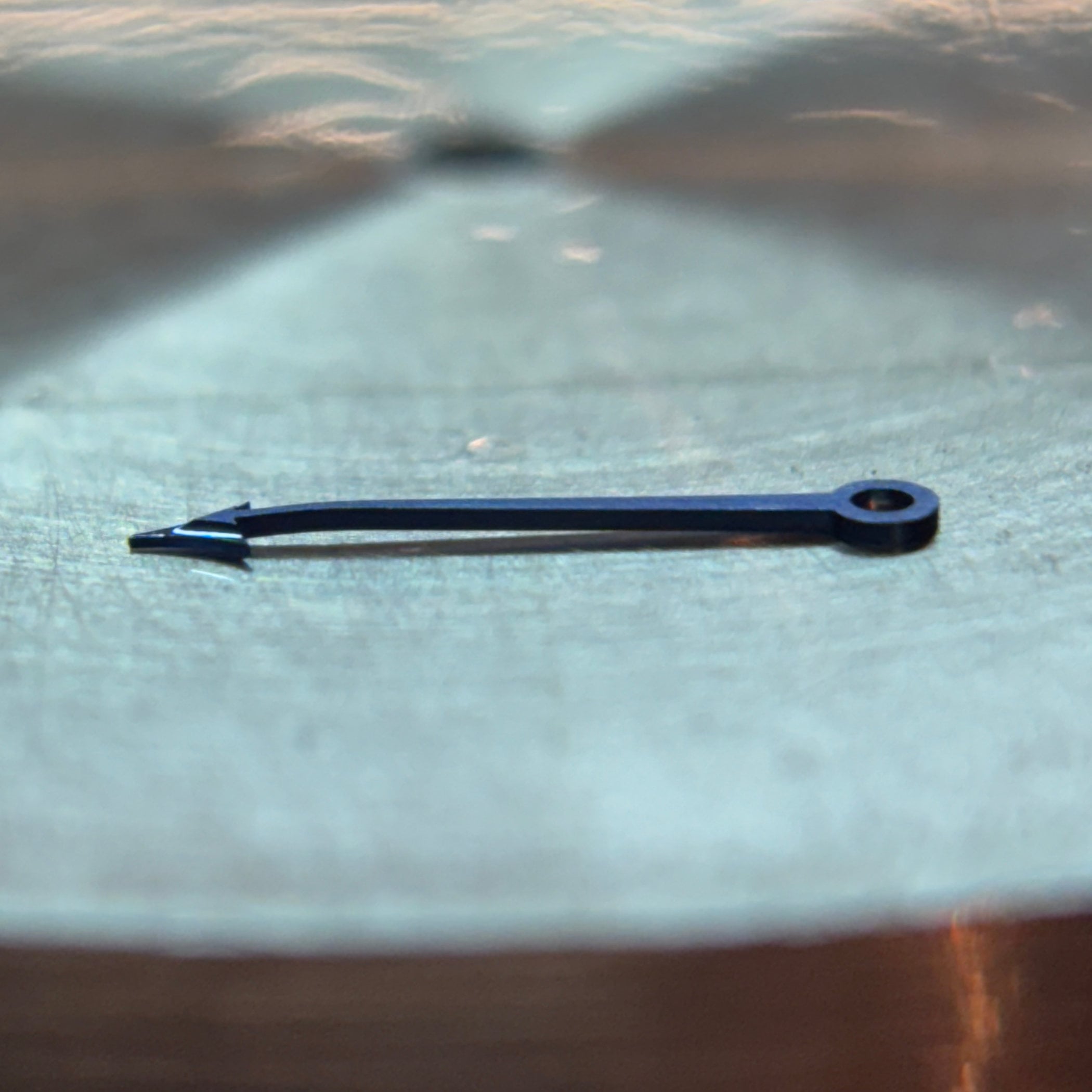

You’ve opted for a Duplex escapement, which is rarely seen these days, especially in a wristwatch. Why that choice?

We chose the Duplex escapement because it embodies a form of horological truth. Where the Swiss Lever escapement, widely used in the industry today, is optimised for industrial robustness, the Duplex belongs to a more artisanal logic. One wheel, two functions, impulse and locking. It is a direct and honest mechanism that shows exactly what it does and leaves no room for cutting corners. It either works or it doesn’t, it’s that simple.

Our Duplex escapement is not a historical replica; we’ve made improvements to ensure it is safe and reliable for use in a wristwatch. It is an entirely new construction, inspired by 18th-century pocket watches, yet completely re-engineered for what we envisioned. It is an homage to the historic Duplex escapement rather than a copy. We’ve used different tolerances, proportions, and materials, and we’ve also integrated several safety features. As our movement puts more torque and power through the escapement, we had to protect it from unwanted shocks and jolts. It took us two years of development to achieve what we had in mind, so a lot of work has gone into it.

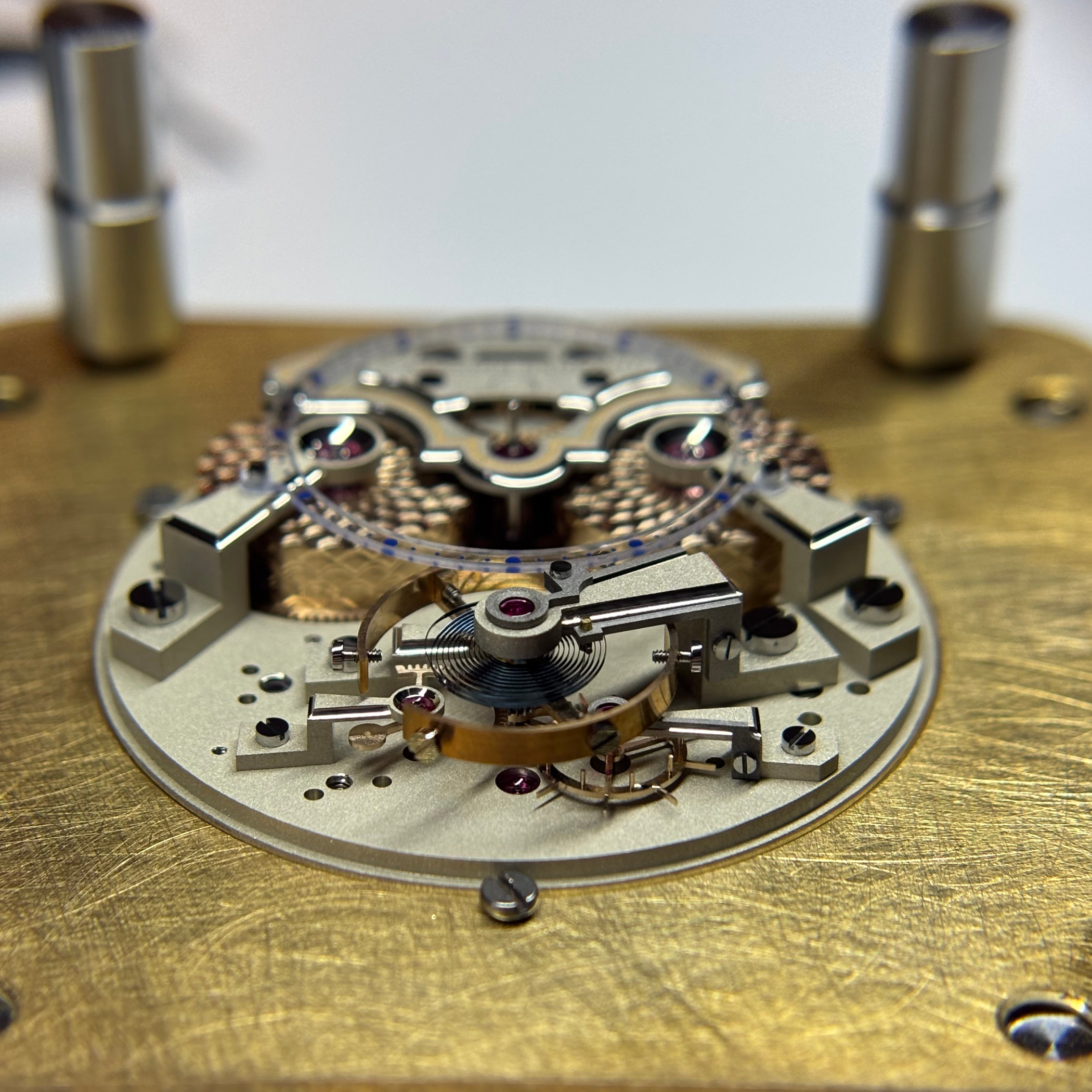

What else can you tell us about the movement design and construction?

The movement was conceived around three fundamental pillars: concave opaline bevelling, fully hand-guilloché barrel covers, and hand-inlaid gold threads on the bridges. Technically, it is a hand-wound calibre, designed, developed and produced entirely in-house (with only three exceptions mentioned earlier). It beats at a low frequency of 1.5Hz (10,800vph) and uses a variable inertia balance wheel that we developed from scratch. It has a rather tall rim, fitted with poising screws to regulate it, and suspended under a single stepped bridge.

The slow frequency gives the watch a wide, almost instrumental breathing, a calmer, more deliberate expression of the passing of time. Despite this, it offers remarkable stability and precision, thanks to the purity of the impulse and the rigour of the machining. As we design every component, all technical decisions are discussed and validated together before being applied or incorporated into the movement.

What were the biggest challenges to overcome?

The biggest one by far was the Duplex escapement. Giving two essential functions to a single wheel leaves no margin for approximation. The geometry of the teeth, the quality of the surface, and the management of energy distribution must be perfectly balanced. Another major challenge was adapting such an escapement to the wrist. Historically, movements with duplex and detent mechanisms were designed to be stationary and not to withstand the shocks they might encounter when worn on the wrist. We therefore developed a modernised architecture that integrates protective behaviour directly into the construction rather than relying on conventional shock absorbers.

Another big challenge was the barrel covers, which are fully functional in construction on the inside, and fully hand-guilloché engraved on the outside. It’s not designed as a pair of appliques, but integral parts of the movements. The pattern seamlessly traverses from the flat top plane to the cylindrical flanks of the barrel, something that we had to develop our own technique for. Each barrel takes about a week to finish, and the work is done on an antique guilloché machine from 1886 that we restored ourselves. Switching from the flat plane to the vertical side requires the guilloché machine to be partially disassembled and rearranged quite a bit, and then calibrated to be as precise as possible so that the lines of the engravings line up perfectly.

Can you tell us more about the hand-finishing?

The barrels reflect our belief that no part of the watch should be neglected, even those that are not immediately visible. The top bridge over the keyless works brings balance and harmony, a structural coherence and visual calm. It acts almost like an architectural element, unifying the movement in a sense. This bridge also features hand-inlaid gold threads, a technique inherited from gunsmith engraving, which Bernard (van Ormelingen) learned over several years working under master engraver Alain Lovenberg in Belgium.

A gold wire is hammered by hand into a groove that’s cut into the bridge. The groove itself is textured to grip the gold wire. The excess material is then removed, and the result is a seamless transition from the bridge itself to the gold wire, creating an outline along the edge of the component. This – as well as the polishing, guilloché and other finishing work – is not outsourced but part of our daily practice.

All finishing is done in-house and by hand, as for us it’s not about decoration but about discipline. There’s no hiding mistakes, no room for error. Each gesture must be precise, intentional and repeatable. It reflects our personal standards and our respect for the components we’re working with, as well as for those who will live with it. The concave bevelling is especially tricky, as in normal bombé bevelling, you can use the full length of a tool over the outer circumference of the part you’re working on. But here you are working on an inner circumference, so you can’t do that. Achieving a perfectly finished concave bevel is much more difficult.

You’re working at very low volumes because it takes a lot of time to create just one watch. Can you share some more details about that?

We make only six watches in this configuration, with three produced this year and three for next year. This is not a subscription series, and production is deliberately limited to what we can personally guarantee in terms of quality and involvement. Each piece can be subtly customised to the wishes of its future owner, while preserving the watch’s DNA. There are certain elements we will not compromise. The price starts at CHF 150,000, and all six have been allocated.

If we talk about long-term vision, what does the future hold for L’Atelier Bernard?

Our ambition is not growth in volume but in depth. We want to continue exploring meaningful horological architectures, refine our craft, and create watches that can be passed down through generations. To us, watchmaking is far from finished and as long as it is not taken for granted, it will remain alive. We’re very pleased to be part of it and hope to be for a long time to come.

The next model is already fully designed on paper, with all calculations done and so on. The bench work will follow soon, but we can’t say too much about it. It will share The Owl’s DNA and our watchmaking principles, but will be a completely new construction with a new movement. Some minor components might be shared, but that remains to be seen.

How can people get in touch to learn more or discuss potentially securing an allocation?

The best way to discover our work is through direct contact. To understand our watches, one must also understand the people behind them, we feel. We are happy to contact with collectors and enthusiasts and take the time to exchange personally. We often create small discussion groups with genuinely interested collectors, allowing for a deeper and more meaningful dialogue. People can contact us about anything through our Instagram channel, and a website is in the making.

You can find out more by checking the L’Atelier Bernard account on Instagram.

1 response

The motto of the watch industry and the big box brands, with or without their jewelry conglomerates is:

“Oh Mighty Dollar,

We Pray to Thee,

For without Thee

We are in The Crapper.”