Face to Face with Omega – A Detailed Visit to the Omega Museum (with tons of photos)

In a previous article, we covered the present state of affairs at Omega, which also gave us a glimpse of what the future holds for the company and for us, journalists and you, potential consumers. Now it is time to rewind the tape of the Omega story and to discover more in details how the company reached this point in its history, by showing you a complete visit of its museum. So, sit back, relax and enjoy the visit to the Omega Museum.

The Omega Museum – Jakob-Stämpflistrasse 96, 2502 Biel /Bienne (Switzerland) – is the oldest museum dedicated to a single watch brand. Located just opposite Omega’s headquarters in Biel / Bienne (Switzerland), it features countless exhibits representing the brand’s entire history, including the original watchmaker’s bench used by Louis Brandt (founder of Omega Watches), when he began making watches more than 160 years ago. Arriving at the museum you are welcomed by a lunar rover – a rather bold statement to what will follow. Up a flight of stairs, you enter the main attraction.

There is one large room where most exhibits await; off to the left is a small room that highlights the very beginning of the brand. There you can see the Louis Brandt working bench with his primitive tools while, in a central position, is the 19-lignes (43.2 mm) calibre that drastically changed the future of the company. Much has been written about the interchangeability of its parts – a fact that made it completely revolutionary, as it could be repaired by any watchmaker. However, its importance lies in the point that this calibre was the first industrially produced movement, with manual-winding and time setting via a two-position crown. It remained in production for 37 years, from its introduction up to 1931. The 19-lignes Omega calibre was replaced by the calibre 43L and later by the calibre 38.5L.

The unprecedented ease of repair and accuracy of these movements, which derived from a high level of precision during the manufacture, led to global success for the brand. We can witness it here at this very room, which splits in half in order to showcase the technical but also the aesthetic quality of the early Omegas. There is a column glass exhibit-case mounted in the centre of the room that is dominated by calibres. The first full calendar watches with “big date” from 1893, others with the new Carillion repetition system from 1894. The previously mentioned 19L, 43L and the 38.5L. The list is huge; the 372 calibre is featured, also bumper calibres and the iconic 55x and 56x movements to quartz and current Co-Axial in-house movements.

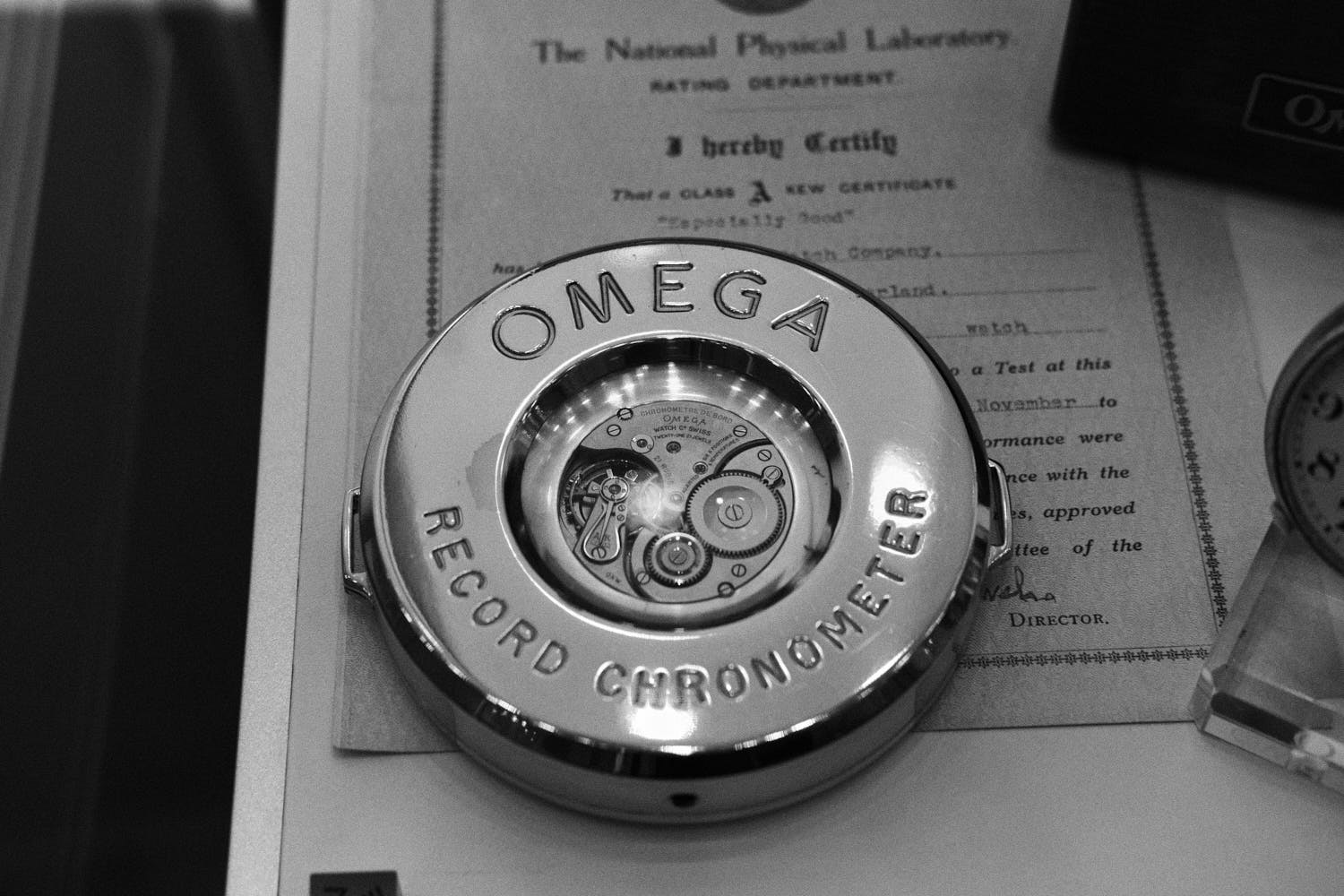

By walking a little further we can see early wrist chronographs, marine chronometers and also mechanical watches that were used in observatory competitions, as well as pocket and wristwatches used in various national railway companies around the world. Here, it is important to note that during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before quartz and GPS, industries, army’s and nations depended on precise mechanical timepieces. Therefore, manufacturers and their master watchmakers spent significant amounts of time and resources on preparations for Observatory trials, which gave them the know-how to build watches that were accurate enough and could be used for various very important applications. For example, we can witness a Marine Chronometer with calibre 20”’ LO DDR in a polished mahogany case from the 1920’s. In the second decade of the twentieth century, OMEGA was routinely producing naval chronometers – that is, officially tested high precision timepieces with a deviation which could not exceed -4 to +6 seconds per day. Their precision movements were secured with a gimbal suspension system that maintained the ship’s chronometer in a horizontal position regardless of the list of the ship.

This ability to combine art with technical excellence is no doubt the reason why OMEGA was the number one Swiss watch brand for decades. The brand’s reputation, as a design powerhouse, started in the very earliest days, with its success at the 1896 Exhibition in Geneva, followed by a Grand Prize in Paris at the 1900 Universal Exposition, with the Greek Temple watch. It represented the façade of a Greek temple with various motifs in relief. The enamel dial, which was painted in black and terra cotta tones depicts Cronos. Other Greek gods and warriors decorate the 18 Ct gold case and two winged griffins protect the temple. Really impressed by this very important but rather neglected period in Omega’s history, you then entered the main hall of the exhibition.

Here you can find everything in segments – and much more. From Omegas involvement in sports, especially Olympic timekeeping, to space Speedmasters and then to deep-sea Seamasters, and from famous Hollywood movie watches (Bond Omegas), to elegant timepieces such as the legendary accurate constellations. In order to see every specimen in detail, you would need at least 3 to 4 hours.

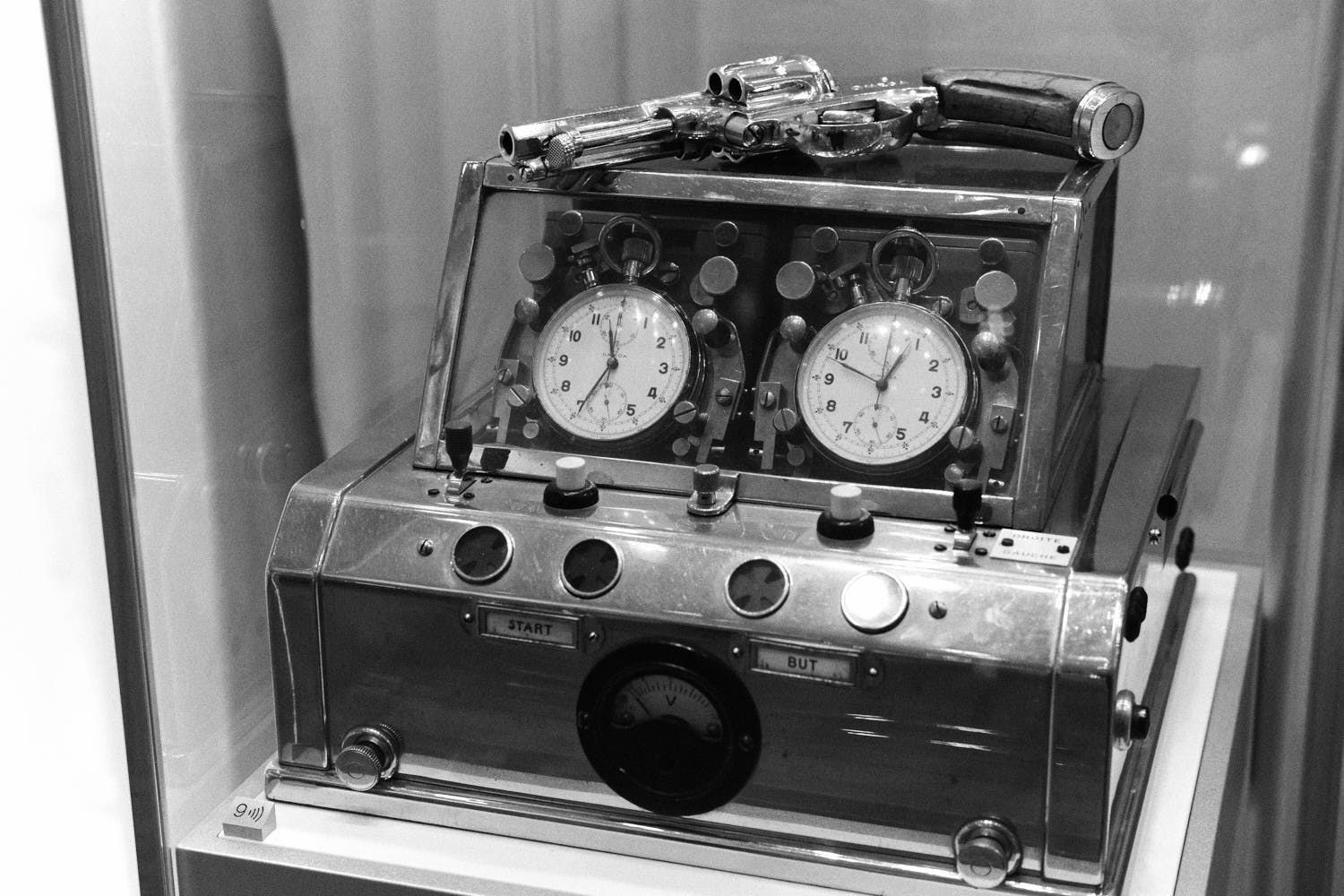

Omega has not only been delivering sports results for more than a century but has also been responsible for the development of some of the most important innovations in the history of timekeeping. Many of the most fascinating equipment are on display at the Museum. It includes chronograph stopwatches that were used at Olympic Games by Omega’s timekeepers from 1932, all the way through the 1960s.

In 1932, ?mega became official Olympic timekeeper in Los Angeles, supplying 30 high precision chronographs, to tackle 117 events across 14 sports contested by 37 nations. All of which had been certified as chronometers by the Observatory at Neuchâtel as well as the National Physics Laboratory in the United States, to be of use across all sports. It was the chronographs’ official certified precision which convinced the Olympic Organizing Committee to select Omega for the Games. Official results were taken at fifths and tenths of a second. On this corner, visitors can marvel at the first fully automated timekeeping triggering box (circa.1940) with start and stop functions in which the start button was linked to the pistol and the stop button linked to the finish ribbon. As well, we see the “Robot timer” that could follow timing of multiple athletes automatically and photo finish cameras used in order to ensure the winner by literally split seconds. Moving forward you can admire a very lovely Seamaster Olympic Melbourne Cross merit with complete box and Cross Merit replica, and also later large stopwatch chronographs.

Here, what struck me was the exhibition case with the Black stopwatches and above all the exceptional Olympic Rattrapante stopwatch. First and foremost, all looked extremely modern, like if they were designed and constructed a few months ago. The rattrapante is very sophisticated since it is purely a mechanical stopwatch that allows its user to time two contestants in the same race, or to determine lap times, or used in competitions where participants are separated by significant lengths of time, or even to time multiple competitors in a run. The “Nuit Spatiale” (“Black Space”) series of the Olympic and sporting event timing equipment were introduced by Omega in 1966, in anticipation of the 1968 Olympic games of Mexico City. This series of sports timing equipment was very extensive, and was designed by Lemania. A two-step black dial characterized all these timers with an extra outer rim for the second markers. This detail, in combination with the extra-long second hands and anti-reflection coatings on the crystal, minimized the parallax error when reading the time, especially through difficult viewing conditions. Last but not least, the case had an anthracite coating, which effectively prevented slippage when holding a timer even with wet hands.

Passing this very important chapter in Omegas history, we can see a showcase that lies there as a demarcation line. A showcase with only three watches inside. Three watches that changed the course of the company forever. The “Holy trinity” of Omega Professional tool watches introduced for the first time in 1957. The Seamaster CK2913 for divers, the Railmaster CK2914 for anti-magnetic needs and the Speedmaster CK2915, the legendary chronograph that was first built for racing drivers, but became famous for a lot of different reasons, much more famous. Finally, the segment with the Speedmasters start and what I see does send shivers down my spine… Every variation possible is right in front of the visitor’s eye.

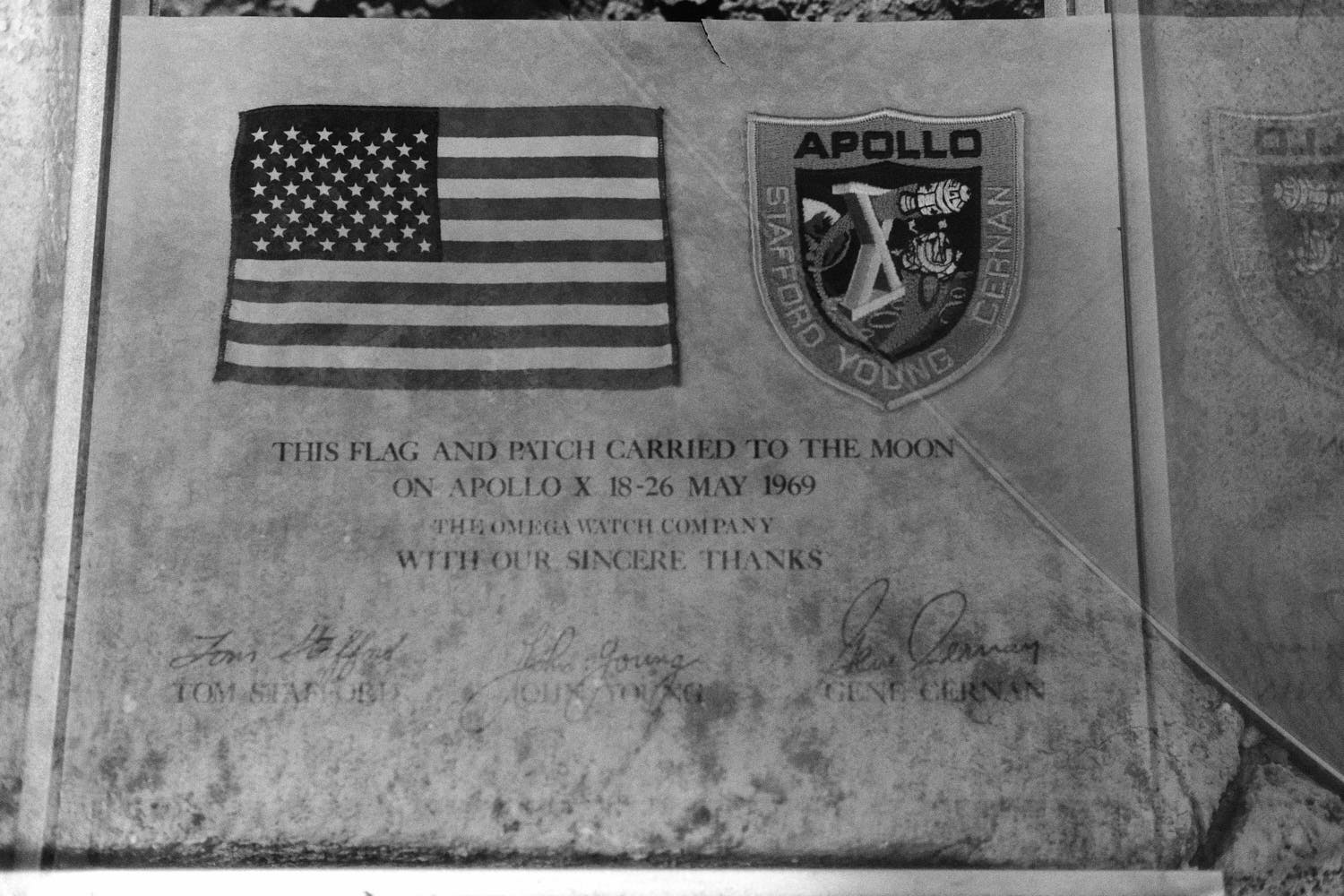

Designed as part of a project between OMEGA and Lemania, the Speedmaster was born as prototype at the end of 1956 and shown to the public in 1957. We can marvel at the archetypal Speedmaster with the reference CK2915, which is known by collectors as the “Broad Arrow”, due to its distinctive hour hand with large luminous arrow tip. Next we find reference CK2998, which replaced the Broad Arrow hands with Alpha hands, while the matt steel bezel was replaced by one with a blackened aluminium insert, to improve legibility. References 105.002 and 105.003 are also there, as well as the 105.012 that was launched in 1963. This reference was chosen by NASA for all manned space flights at the end of 1965, due to its more robust case – and despite the fact that the watch tested was actually a 105.003. The Speedmasters of Don Eisele, a command module pilot for Apollo 7 and Tomas Stafford, commander of Apollo 10 and the Joint Apollo-Soyuz mission, are also showcased at the Omega Museum, with all sorts of memorabilia collected or bought by the museum staff.

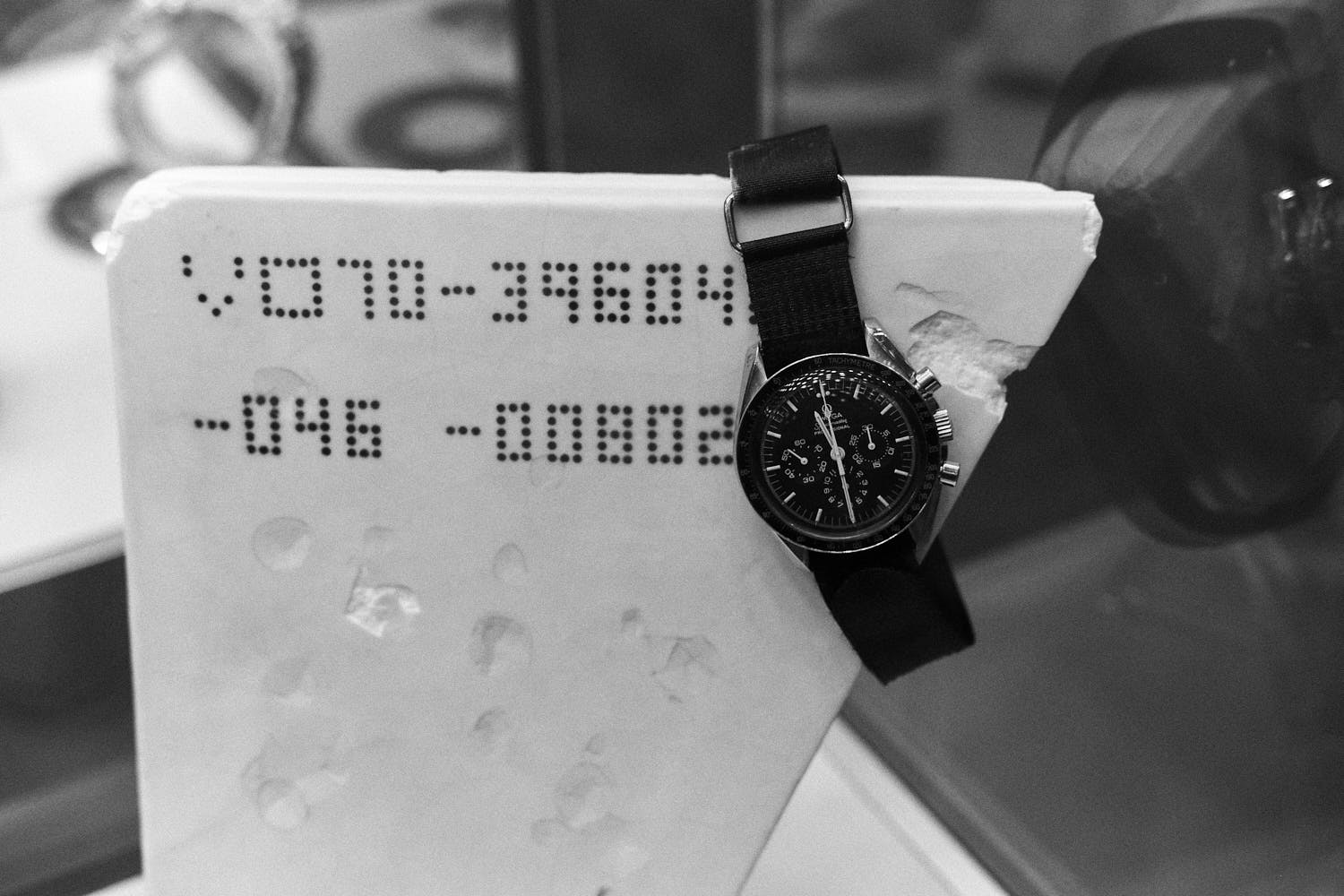

Reaching the bottom of the main hall and looking around, there are so many important Speedmasters that I started to become dizzy. The corner is overviewed by an Apollo Block II A7L EVA-Moon suit while a little bit further on is a case with a Speedmaster Moonwatch strapped on an astronaut’s glove, remembering me of all these stories of the Apollo program, stories that I grew up with. By turning around the corner, we start viewing the transformation of the Speedmaster with the all-gold 1969 Speedmaster Professional Deluxe and the Mark II. The Speedmaster Professional Deluxe was created to celebrate the Apollo 11 Moon landing, with the first examples being given to all the astronauts active in the US space program, as well as other prominent individuals, including President Nixon, who politely refused the watch due to its high value. The Mark II was the first of five Mark watches and began what was to become true diversification in the Speedmaster range. It was at this point that the Speedmaster became a line on its own right due to findings from the Alaska Projects that passed on regular production Speedmasters.

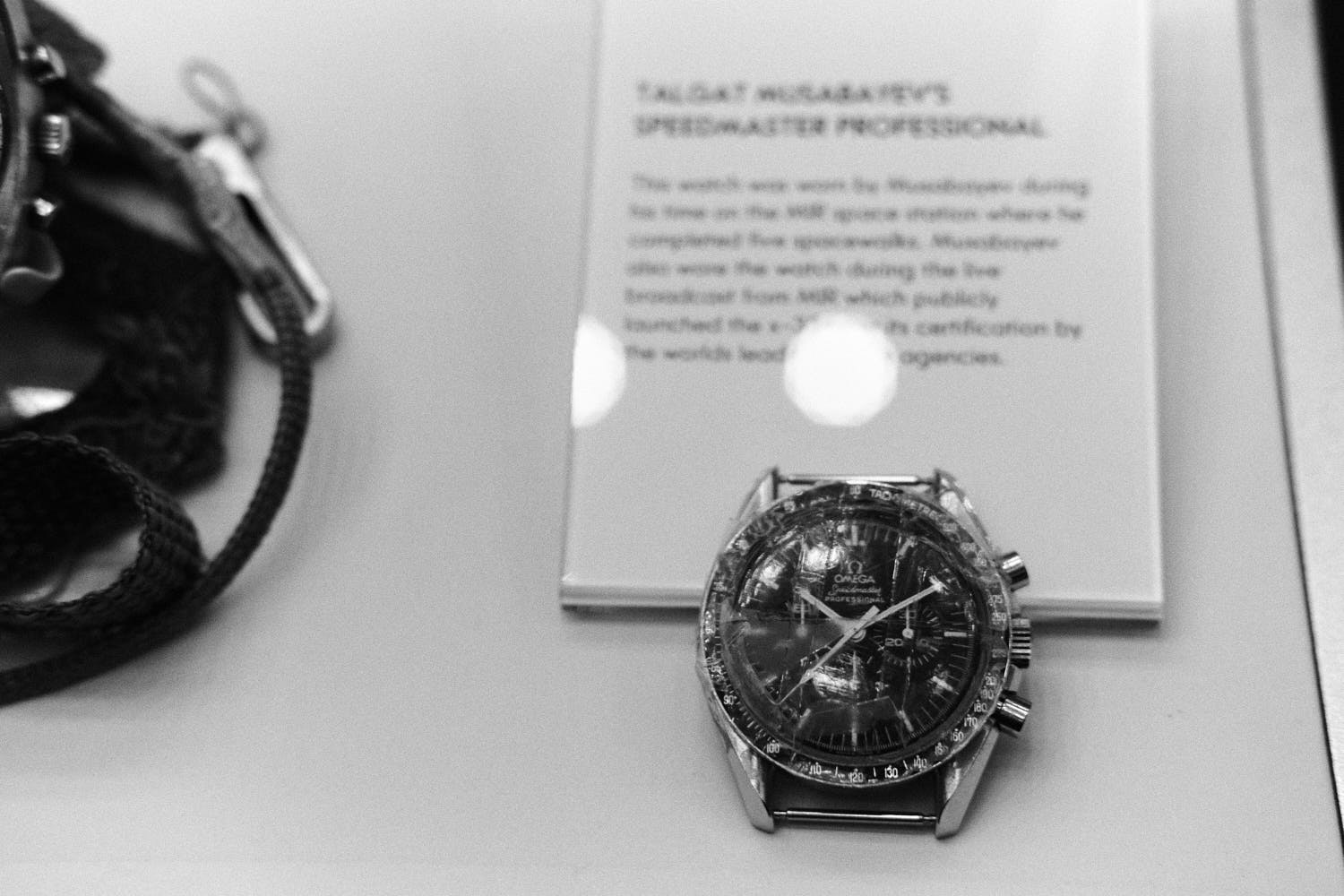

Throughout the 1970s, this diversification would continue with the addition of more complicated models, with for instance the first series-produced self-winding chronograph to be certified, the chronometer Speedmaster 125, which was introduced in 1973 to mark OMEGA’s 125th anniversary. In parallel, this was the era of electronic watches, which also applied equally to the Speedmaster with the addition of the “Speedsonic” (with its tuning fork movement), the Speedmaster Quartz and Speedmaster Professional Quartz – which were both multi-function digital watches. On this section, the visitor can marvel, among others, a radial Speedmaster Moonwatch (Project Alaska III 1978) suspended from a thermal protection HRSI tile, used at the Space Shuttle program by NASA, or the very first Alaska I Speedmaster prototype with a titanium case, circa 1969 (the first titanium cased wristwatch). We can also find literally all the Mark references as well as the recently highly coveted Soyuz Speedmaster. What struck me here was the Speedmaster 125 worn by Vladimir Djanibekov in 1978 on his Salyut 6 mission, Talgat Musabayev’s battered Moonwatch worn onboard MIR and the infamous Mark 4,5 Speedmaster, which was modified by Mr. Daniels with his co-axial escapement and used by him to convince Mr. Hayek to adopt his innovation. A very important specimen for Omega!

Last but not least, before entering the Seamaster section of the museum, we find showcases with X-33’s and also other professional aviation tools like the iconic Flightmaster, in every conceivable variation. Even a solid gold one is on display; one of the heaviest wristwatches in history and a choice of the late King Hussein of Jordan. The Flightmaster displays contain of course instrument panel clocks used on the legendary Concorde Supersonic Jet-liner. Omega’s instrument panel clocks equipped the prototype supersonic airliner from 1967 and were subsequently part of every commercial flight from the first in January of 1976 until it was retired in November of 2003. A bit further, I marvelled at the Railmasters and military issued Omegas like the legendary 53 model given to the RAF navigators and pilots coupled as well with the glass cases showing Constellations, with of course their COSC certificates playing a prominent role in their display.

Sadly, time started to run out and I had to stop thinking about my heroes that wore these watches and in parallel, I had to stop dreaming and drooling in front of every display case. When entering the Seamaster’s room, we see an equally important line of professional tools for Omega, along with the Speedmaster. Yet again, the Omega Museum’s collection is impressive, to say the least. Seamaster watches of every conceivable reference can been seen, from the very early CK2913 to the Ref.165.024, issued to the Royal Navy military divers, and to watches used by the iconic Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s team, during its “Precontinent II” experiments in the Red Sea in the summer of 1963 – in order to prove that divers could live in a submerged saturated gas environment for long periods without adverse effects.

The ever-increasing depths at which divers were working led to the creation of the famous “Ploprof” (PLOngeur PROFessional or “professional diver” in English) Seamaster 600, launched to the public in 1970 after four years of intensive research and testing. This watch proved to be more than adaptable to the new challenges faced by professional divers and naturally, it monopolizes the display cases along with the another behemoth of the deep, the Seamaster 1000 which was launched in 1971. It was created and tested alongside the 600 and was also tested and used by the same divers. The highlight of the 1000’s early exploration career was undoubtedly its dive on IUC’s (International Underwater Contractors) submarine “Beaver Mark IV” where the watch was attached to the submarine’s robotic arm to test the effects on the crystal at a depth of 1000 meters.

Various prototypes are displayed in this section, to demonstrate Omega’s pioneering spirit and bold design solutions. Here we can check watches that entered in production like the Seamaster 120 Chronograph, which collectors named the Big Blue, the Yachting chronograph with the fabulous 1040 calibre or Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s personal favorite, the Marine chronometer. This wristwatch, with its integrated bracelet and its quartz calibre, was the first wristwatch ever certified as a Marine Chronometer. Developed by John Othenin-Girard, it was one of the most accurate non thermo-compensated production watches ever made. This wristwatch (ref.1511) was certified by the Besançon Institute. All 1000 examples that were ever produced had been sent for testing their chronometer status and after 63 days of relentless testing, the mean variation was astonishingly less than 0,002 seconds per day!

Last but not least, the visitors can marvel at early Seamaster chronographs with the 321 calibre as well as other references of the 1970’s and also the 1980’s. Here we must point out what the Omega Museum states: “other than recording and making diving history, the Seamaster line was also the home for much of the brand’s research into alternative case materials and treatments that included titanium in the late 1960s, tungsten and PVD in the early 1970s, ceramics in the late 1970s and forged carbon in the 1980s; many of the designs in these exotic materials actually made it into production”.

Suddenly I realized that time for me had run out. I could happily live in the museum premises for a few days, in order to recollect stories about the people who made these watches and the people who wore them. Stories about exploration and experiments, stories about bravado and drama, stories of evolution and design. This visit made me think that the raison d’être of the tool watch has changed rapidly. This is currently driven by the industry and by the consumers as well. The Omega Museum is a glimpse into the glorious past, when watches were worn for the job, for what they were built for, long before collectors and social media took over and of course, long before they were considered glorified jewels.

O Tempora O Mores screams the romantic side of me, while my rational side thinks about the evolutionary course of wristwatches in general and of the Swiss horological industry. No matter how you look it and the angle you’ll choosen a visit to the Omega Museum is a must for everyone who wants to better understand the wristwatch and its role in the history of human achievements. www.omegamuseum.com and www.omegawatches.com.

10 responses

Black and white….really? Most of the watches are dark faced. Thanks fir the useless pictures.

Have always been a big fan of Omega.

So thank you for such an informative article.

Very good follow up to the recent article you did on Omega.

Wonderful article, really look forward to visiting in person!

The photos are great too, can I ask what camera/lens combo was used? They have a strong Leica feel to them.

Thanks for a great read – love the black and white pictures, which compliment the watches just perfectly. Great job………….

Colour, please.

Thank you guys for the comments.

@Cris.Rose. I used a Fujifilm XT10 with a 35 f2

Nice article, but have to agree with others who has commented before me.. Black and white pictures is not the way to go here :-/

I have had for thirty years one gents 9ct yellow gold Omega wrist watch. The watch has wire lugs press in back case It is a very flimsy back case that is paper thin (not worn). It appears to have original dial . This watch is in my safe in Cape Town South Africa therefore I am unable to show picture at this time as I am overseas until mid January 2017 . It is a very thick watch maybe 5 cm deep . The icing on this cake is, that it is self winding watch circa late twenty’s or early thirties. IT must be an extremely rare time piece, and is in working order. . Can anyone advise as to when the first Omega self winding watch was produced . I have a feeling this watch may be an example

Andrew if i am not mistaken Omega’s first automatic movement, produced from 1942 to 1949 and its name was calibre 28.10 RA PC, later renamed Cal.330. It would be nice to see some pictures of the watch you have. Cheers.Ilias

how stupid is it to leave BW pics.. might as well just do text