The 10:10 Position of Hands is so Deeply Rooted in Watchmaking that AI can’t Generate Anything Different

When things are so widely accepted and rooted in the common psyche, even the best AI image generators are brainwashed to follow the norm.

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is on everyone’s lips. It’s a topic that divides and generates strong opinions (pros or cons), and it will, in the future, become increasingly important, whether you like it or not. These tools, at least the tools that we, the public, can use (image or text generators such as ChatGPT), are becoming better and better at being creative – just ask AI to write an 800-word article about the history of the tourbillon regulator, and you’ll see that, even if the result is slightly sterile and generic, it’s not that bad. When it comes to generating images, these tools are also fairly impressive, but they have their limits. One of them is to deal with firmly anchored concepts, images that are so deeply rooted in the common psyche that they can hardly be counteracted. One of them is the 10-past-10 position of the hands in watch marketing and creative imagery; it is so strongly embedded that AI can hardly do anything against it.

The reason behind this article lies in some of our team members finding a discussion (video below or visible here) between Youtuber and Stanford University member Robinson Erhardt and Ned Block, a Professor at New York University in the Departments of Philosophy and Psychology. In a section of this video named “How to Show that ChatGPT Is Dumb” (starting at 45:53), Professor Block explains that he has tried and failed when asking OpenAI tools to “draw a picture of a group of watches showing 3 minutes after 12”. The vast majority of results showed watches displaying 10-after-10.

The reason for these results, as he explains, is that “pictures of clocks and watches on the web are dominated by 10-after-10 because it’s the most attractive look”. Of course, this tickled our interest here, and since we don’t usually take things for granted, we had to try that out for ourselves. But before that, let’s look back at the famous 10:10, 10-past-10 or 10-afer-10 position of the hands on watches.

The case of the 10:10 position of hands

This subject has been studied many times, and dozens of articles deal with this topic. But let’s quickly look at it again. Why, for the vast majority, do images of watches produced by brands have the hands displaying the time at somewhere around 10:10? Sure, it can be 10:09 or 10:08 in some instances, but you get the idea. Most official images produced by watch manufacturers use the 10:10 display. There are some exceptions, such as Parmigiani Fleurier (hands at 07:08, supposedly the time of birth of founder Michel Parmigiani), Oris that always indicates 07:53 or A. Lange & Söhne with the hands at 01:53 (but the result is visually identical to 10:10).

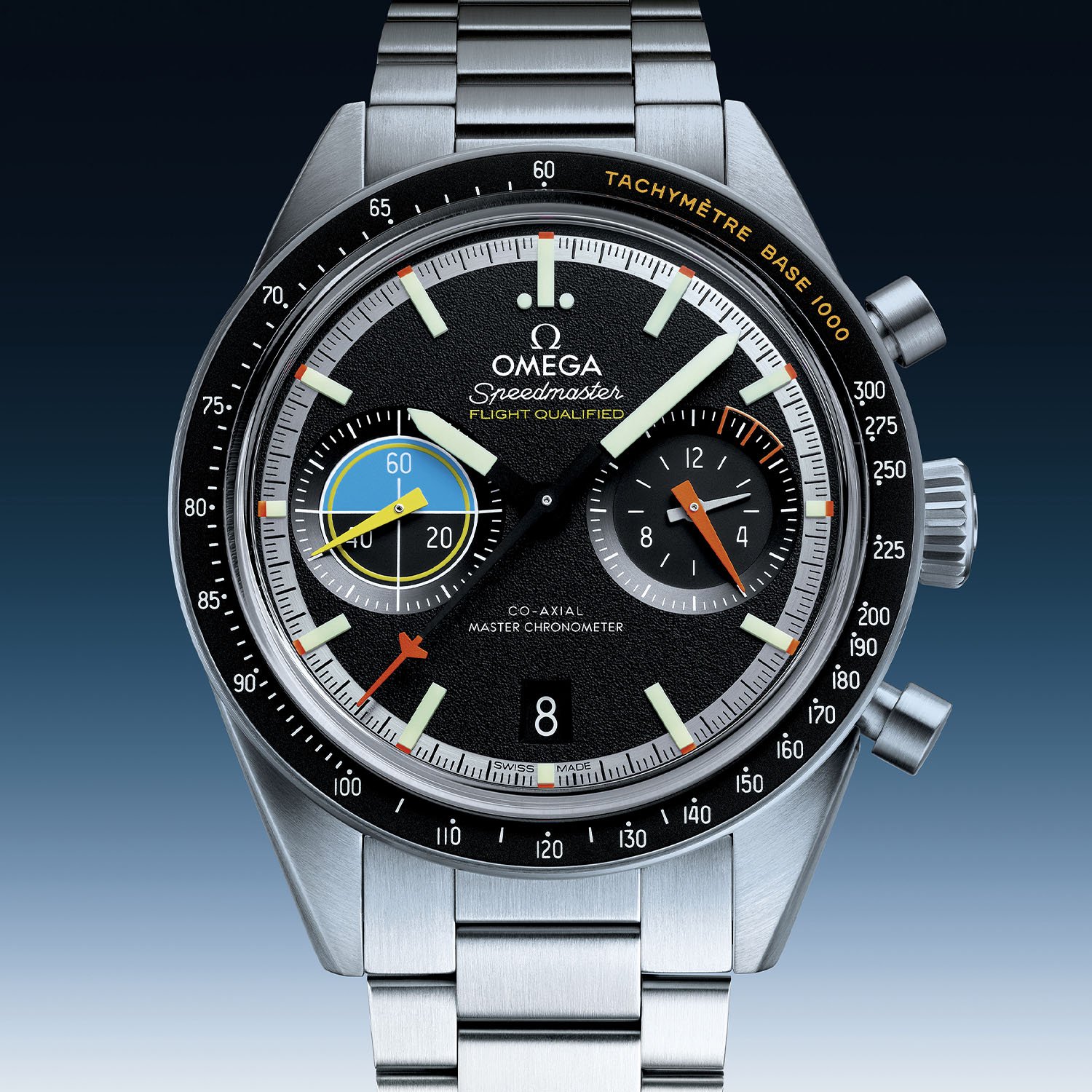

But take Rolex, Omega, Patek, Audemars or basically every other watch brand, and you’ll see that official renders and images have the hands positioned somewhere around 10:10. To be precise, Rolex always produces images of its watches with hands at precisely 10 hours, 10 minutes, 31 seconds, and the date on the 28th of the month (see here, here and here). For Omega, it’s always 10:07 and 37 seconds.

Why are the hands in this position? It’s a marketing trick that has been around since the 1950s and has become an industry norm. There are multiple reasons to explain this position of the hands; first and foremost is the symmetry it offers – it is widely known that the human brain is attracted by symmetry. Also, the hands positioned in this way form an approximate angle of 120 degrees that both frames the logo (most of the time, the brand’s logo is located at noon, under the marker) and avoids overlapping potential subcounters on the dial – for example, when chronographs and calendars have sub-dials at 3 and 9 o’clock. Finally, it forms an aesthetically pleasing smiley face, once again to attract our subconscious. There are even psychological studies about this, such as the present one, “Why Is 10 Past 10 the Default Setting for Clocks and Watches in Advertisements? A Psychological Experiment“, published in Frontiers In Psychology.

AI image generators and the difficulty of dealing with anything else than 10:10

So, back to the main topic and what Professor Block and Erhardt discuss in the video to demonstrate that ChatGPT can sometimes be dumb – yes, that’s a bold statement. As said, these two are taking the example of watches and have tried on multiple occasions to generate images of timepieces displaying a specific time on their dial. Their results, using ChatGPT, were clear; most, if not all, the images produced dials with a time set at 10:10. Of course, we had to try that for ourselves, and I’ve been testing this with different requests to the built-in AI image generator of Adobe Photoshop. My results… Well, see for yourself below.

For this first image, I requested that Photoshop’s AI tool create “a wristwatch in an elegant setting, with the time adjusted at 06:35”. As you can see, we definitely have a wristwatch, but the hands are in the classic 10:09 layout.

Next up, we have a trio of images using the same built-in AI tool, this time asking it to create “a pocket watch with a historical layout and the time adjusted at 2:45”. Once again, you’ll see pretty realistic pocket watches – I must admit that the results are quite convincing – but once again, all three display the time we’ve been used to seeing on most watch advertisements, meaning around 10:10.

Then, I performed another test by asking the AI tool to create an image of “multiple watches, all with the time adjusted at 6:35”. Again, the result was disappointing. Some of these watches display different times, but the overall quality of the image is fairly poor, as if the tool was overwhelmed by the request.

I then decided to be very simple in my requests, asking Photoshop to create an image of “a watch that indicates exactly 02:35 with its hands”, again, not with much luck. This image is one of six results provided by Photoshop, but they all basically produced the same image and time.

I then tried to trick the system, as Professor Ned Block suggested in his video. He managed to get results with digital watches displaying the right time; of course, this time, hands did not enter the equation. My request was simple: “a digital sports watch that indicates exactly 2 PM on its screen”. As you can see from the images generated, I was not very lucky.

What does that tell us? Well, AI is, by nature, creative, but it has its limitations. AI relies on existing concepts and sources to generate text or images based on a request, building its answers with what is available on the web. I have tried on multiple occasions to ask ChatGPT to write articles about very recently released watches, but no relevant results were possible – simply because of the lack of available sources. However, if you ask ChatGPT to write an article about a well-studied historical topic – the creation of the tourbillon, the history of the Rolex Submariner – the results are generic and sterile (they lack a human touch and style), but the content can be pretty satisfying.

Regarding imagery, AI generators work on the same principle; they look around the web and generate images in relation to your request. As Ned Block says in the video, “pictures of clocks and watches on the web are dominated by 10-after-10 because it’s the most attractive look”. Block also mentions that people from OpenAI are aware of this situation but are unable to fix it. There are ways that such issues can be counteracted by using a process called “reinforcement training”, where you teach the machine to do things differently than what is widely available on the web. Here, however, there are too many different occurrences that need to be reinforced – basically, the system should be reinforced by 719 other positions than the classic 10:10 layout, as there are 720 positions possible on a classic 12-hour analogue watch (12 positions for the hour hand multiplied by 60 positions for the minute hand).

Other “bugs” in the AI matrix…

The 10:10 hand position is one of many examples that Professor Block mentions in this video. He also talks about the prevalence of right-handed writing over left-handed writing. He explains that if you “ask ChatGPT to draw a picture of somebody writing with her left hand”, you’ll always end up with a right hand. Even by using various tricks, he could hardly overcome the issue, only by using complex chains of requests. As an example, I’ve also asked Photoshop’s AI tool to generate “a left hand writing in a book”, and here are three of the results I obtained (and many more in the same vein), all with a right hand.

And because we’re also car enthusiasts, I asked the same tool to generate an image of “a right-hand-drive car dashboard” only to get pictures of dashboards without a steering wheel or images of LHD cars – I’m pretty sure that with the correct chain of requests, I would have been able to deal with that specific issue, but then again, the initial results are based on web searches dominated by LDH cars.

I’m sure that these issues will be solved, but this specific example, which is watchmaking-related, was certainly worth exploring. And if you feel like it, have fun and try these examples for yourself, maybe with different AI generative tools than the one we’ve used in this article. And please share your experience in the comment section below.

Note: all images in this article, with the exception of the images of real watches used in the first section, have been generated using Adobe Photoshop’s built-in generative tool and are simply used as examples and illustrations of the possibilities of such tools.

2 responses

It’s not a bug in the AI matrix. Basically what we refer to as AI is really a trained large or small language model. It is machine learning, rather than intelligence.

So you have an algorithm, you have a set of training data, and you teach the machine to regurgitate rehashed bits of that training data set based on what statistically seems to be the most commonly seen answer.

Quite a few of these have been trained by means of unsupervised learning, where the LLM simply absorbs whatever data you chuck into them without too much guidance. You can go down the route of supervised or iterative training so as to improve results for your niche, but there’s not guarantee it will yield the right result, and you can forget about the same straight answer twice in a row.

In short: the problem is that lay-people call AI intelligence when in reality it’s an algorithm-driven regurgitation machine that is as dumb as a brick. And then they use it for incredibly trivial questions, like generating fictional watch faces, in spite of the huge carbon footprint of the datacenters that churn out this meaningless stuff.

If anything ever illustrated why mankind is doomed to boil the atmosphere, it’s AI.

The reason the hands are at 10:10 is the time when Abe Lincoln was shot. I’ve heard that story for years.