The Clock that Changed the World and the Fantastic Recreation of John Harrison’s H1

Bob Bray’s replica for jeweller Pragnell is the first at full scale and the most complete yet.

The replica of John Harrison’s H1 clock that the Stratford-upon-Avon-based Pragnell’s commissioned from Bob Bray of Sinclair Harding is a gloriously over-the-top tribute to an invention that was as significant an advance in the 18th century as the emergence of AI is today. Indeed, John Harrison’s H1 clock cracked the Longitude Problem, making navigation at sea accurate and safer – and that, back in the days of maritime exploration and trade, was nothing short of a game-changer. And this is why John Harrison is often referred to as the inventor of the marine chronometer.

Editor’s note: This article has been written for MONOCHROME by author James Gurney (gurneygraph), who writes about watches for leading international titles, including The Telegraph.

The comparison with the emergence of A1 may sound hyperbolic, but it stands. The struggle to determine longitude at sea will be well known to some of MONOCHROME’s readers, yet bears repeating. Throughout the 17th century, Europe’s maritime trade exploded, as did the naval power protecting it. One problem, however, remained stubbornly unsolved: finding longitude. Latitude was easy enough to observe, but longitude required comparing local time with a fixed reference – the difference translating into degrees east or west. The danger became brutally clear when a fleet commanded by the wonderfully named Sir Cloudesley Shovell struck the Scilly Isles after a longitude miscalculation, killing 1,400 men and destroying ships worth £20,000 – roughly a tenth of the government’s annual budget.

The device that solved the Longitude Problem

In 1714, the British government offered a £20,000 prize. Aside from the inevitable parade of quacks and opportunists, the rational solution lay in comparing local and reference times with far greater precision. The target was half a degree of longitude, around 20 miles at Greenwich’s latitude, requiring accuracy of about three seconds per day – achievable on land but hopeless at sea. Attempts by Galileo, Huygens and others to build reliable sea-going clocks had already failed. The alternative, astronomical tables tracking lunar distances or Jovian eclipses, was equally impractical for sailors.

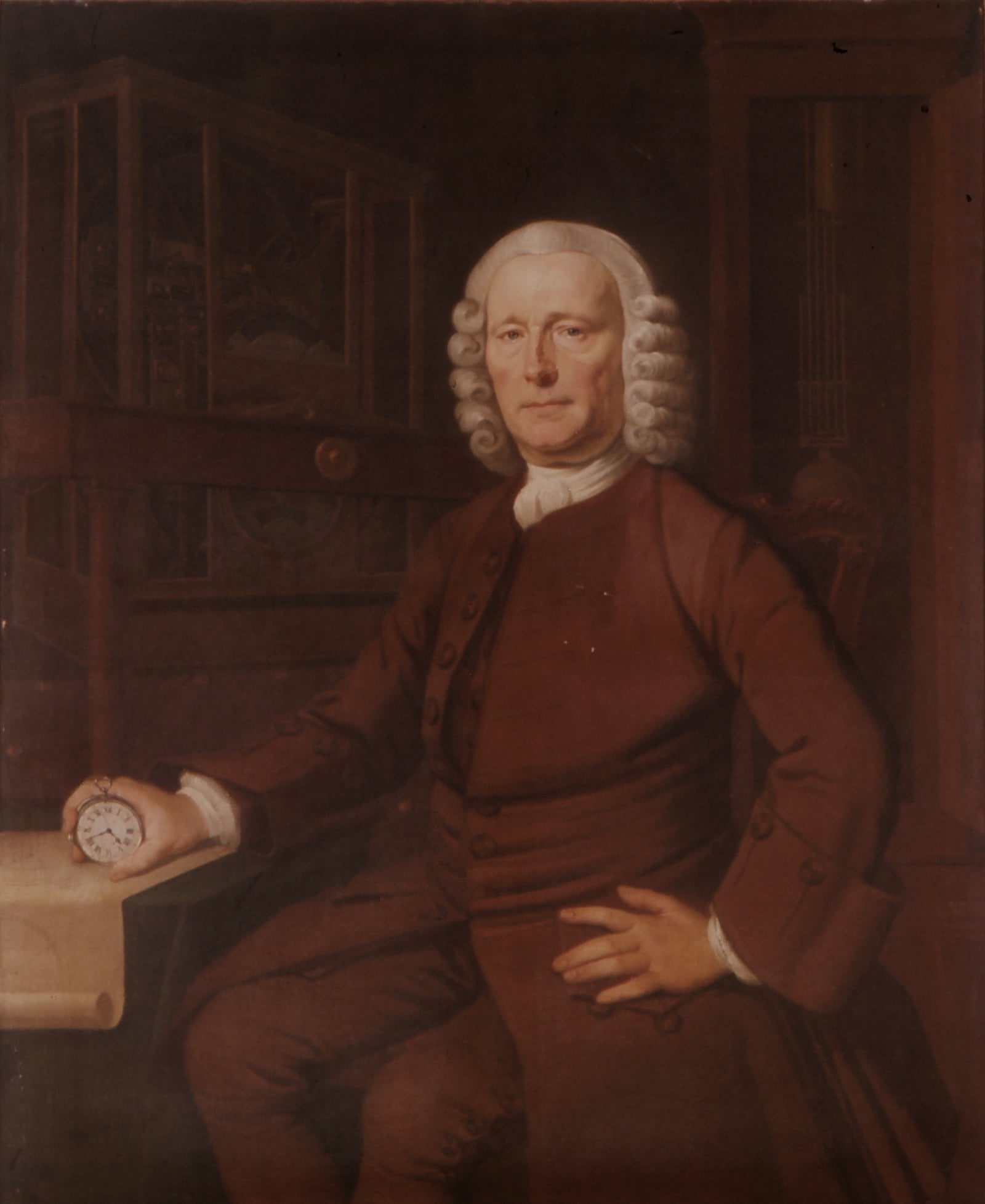

Then came John Harrison, a Yorkshire carpenter’s son and autodidact. He built his first clock in 1713, largely from wood, exploiting its mechanical properties to offset the lack of metal. Over the following decade, he invented the gridiron pendulum and grasshopper escapement, achieving errors as low as a second per month – outperforming masters like Tompion and Graham (who was to become his mentor). Convinced a marine clock was possible, he began his Longitude prize work in 1730 and delivered the H1 marine timekeeper five years later.

The point is that Harrison put existing technologies together in a novel manner to create a paradigm leap in performance that had profound effects on global trade and power, for the benefit both of Britain’s Navy (already accounting for 5% of GDP – that enough, Donald?) and the trade it secured.

John Harrison’s H1 clock itself is astonishing both in scope and sheer inventiveness. Harrison had already made longcase clocks that were approaching a second per month, easily within the precision required by the government, but he re-examined every element in his bid to make that precision seaworthy.

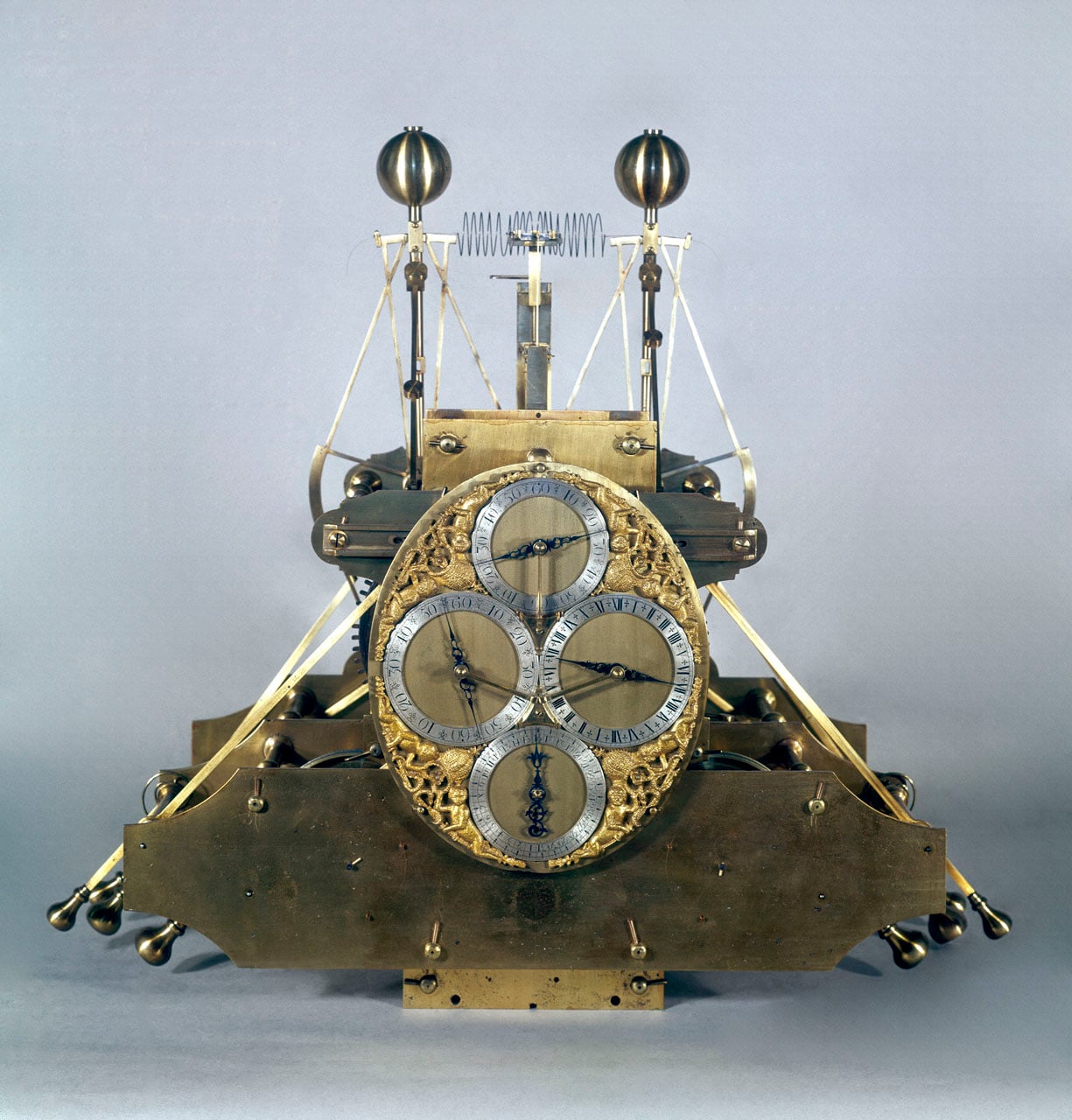

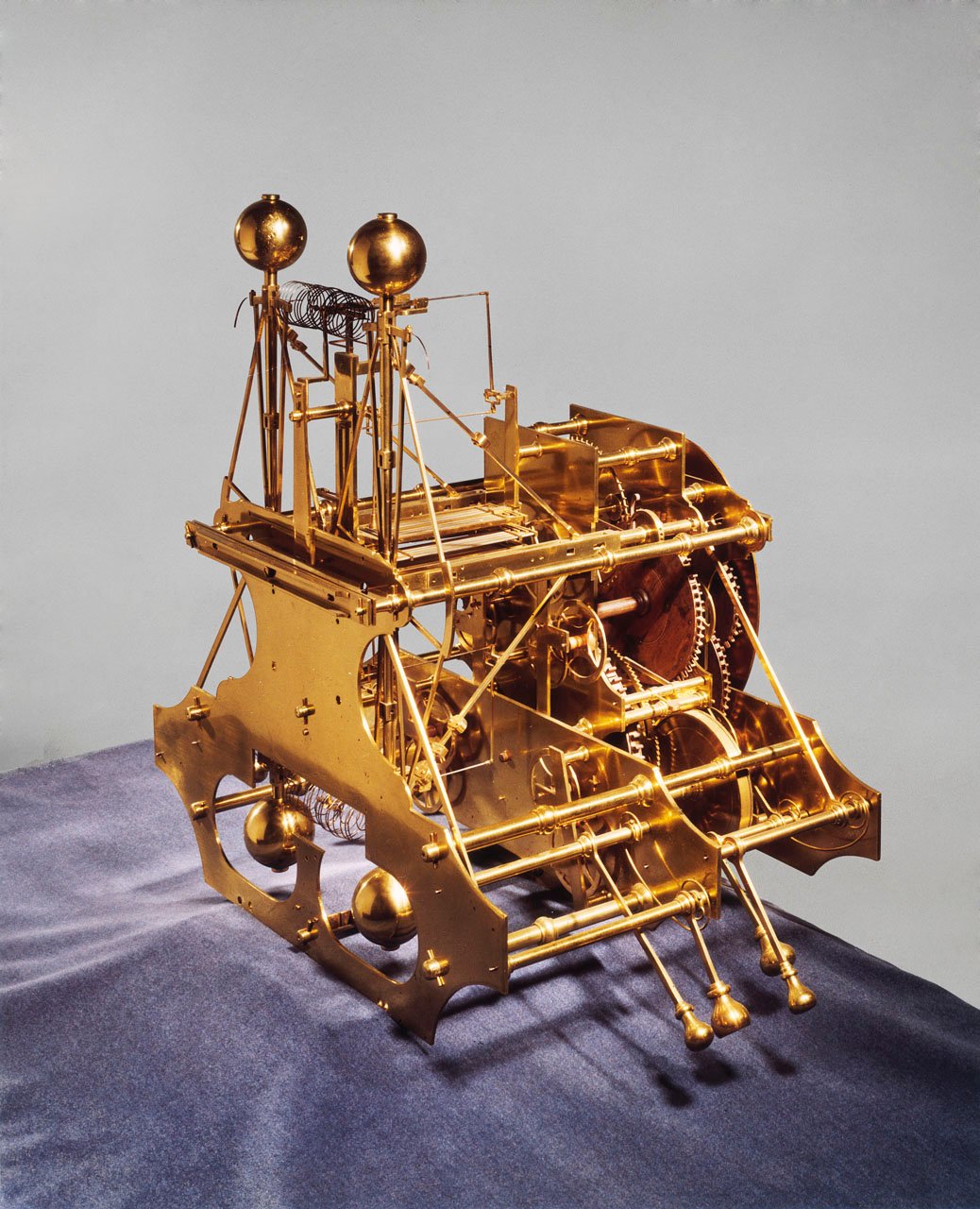

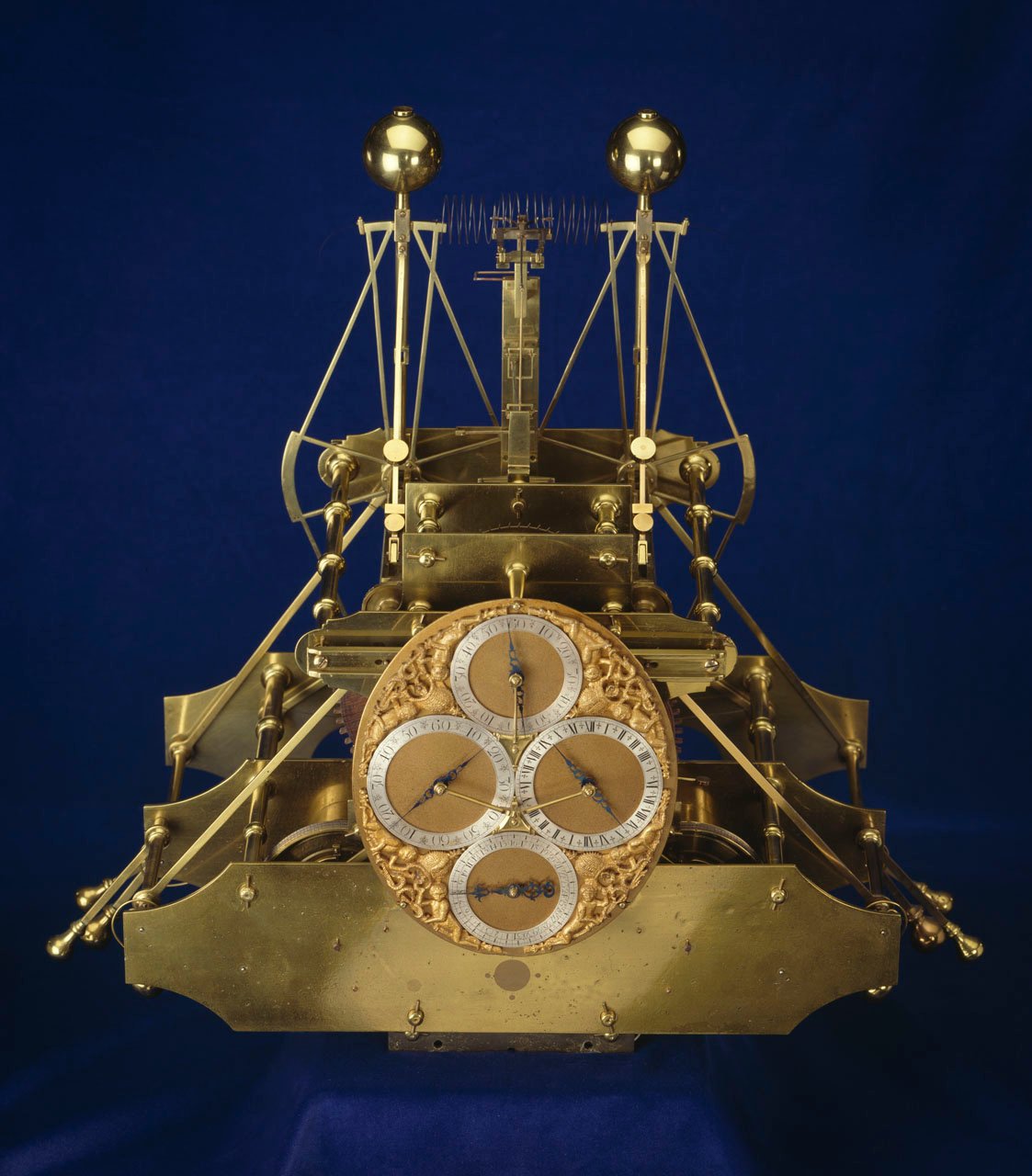

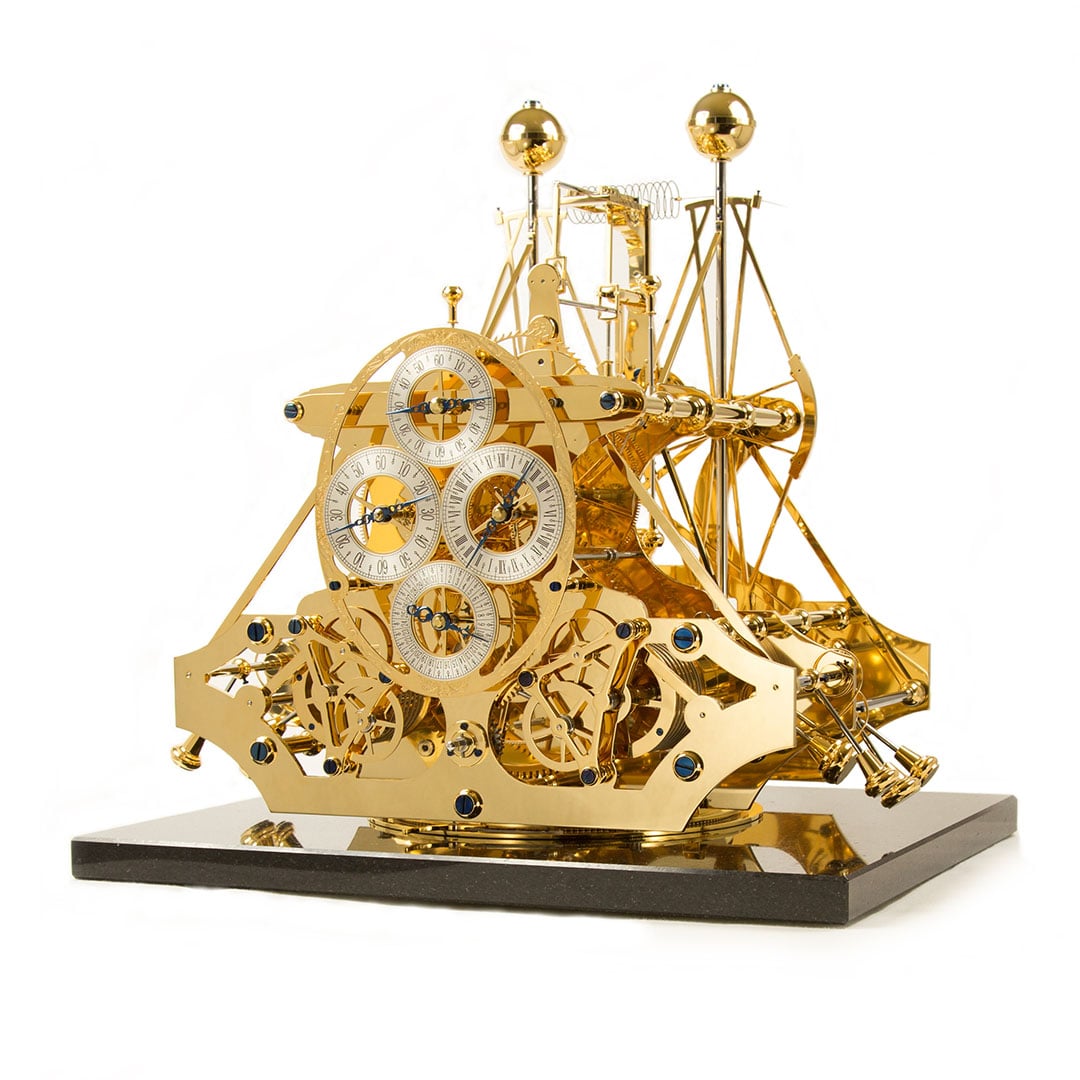

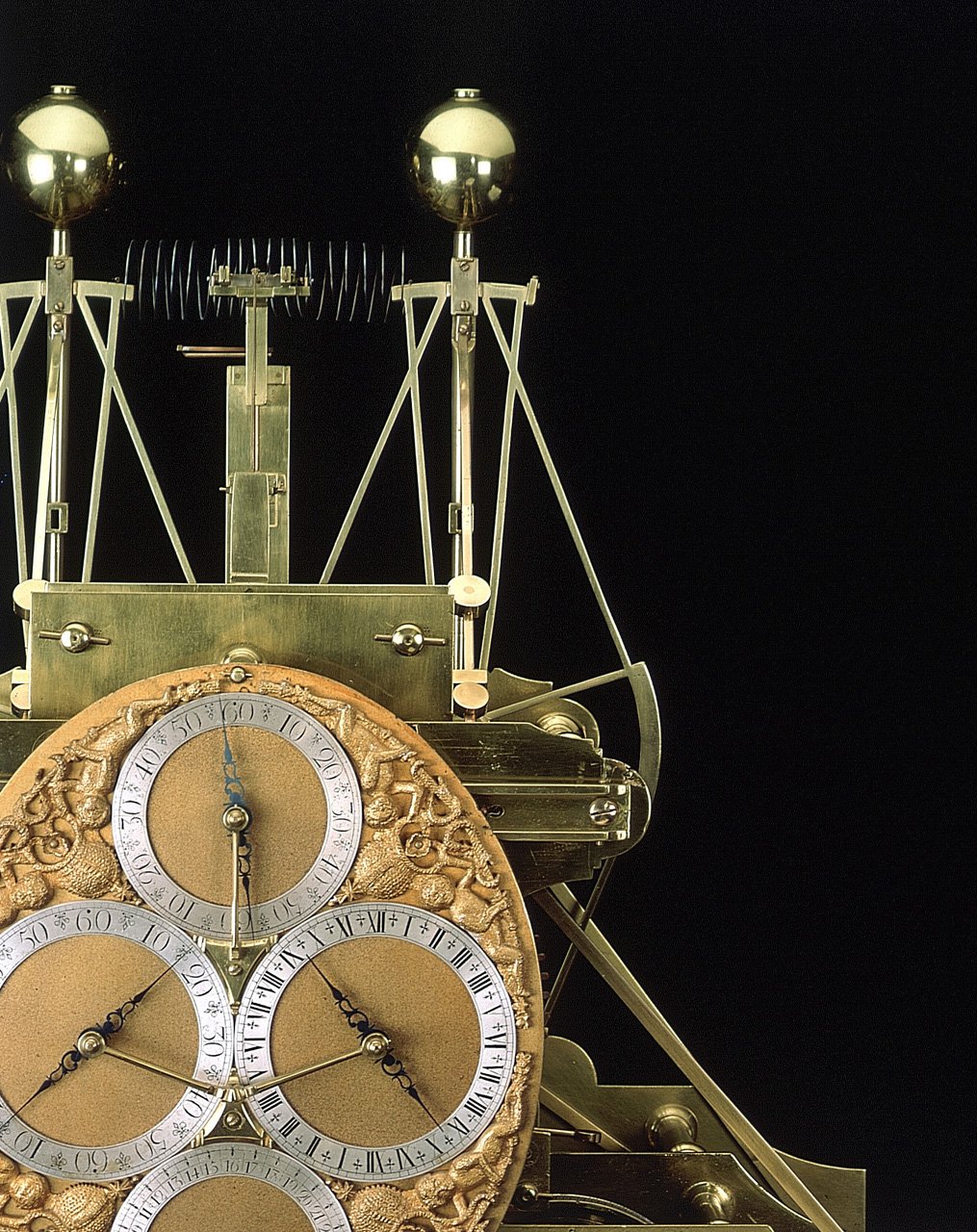

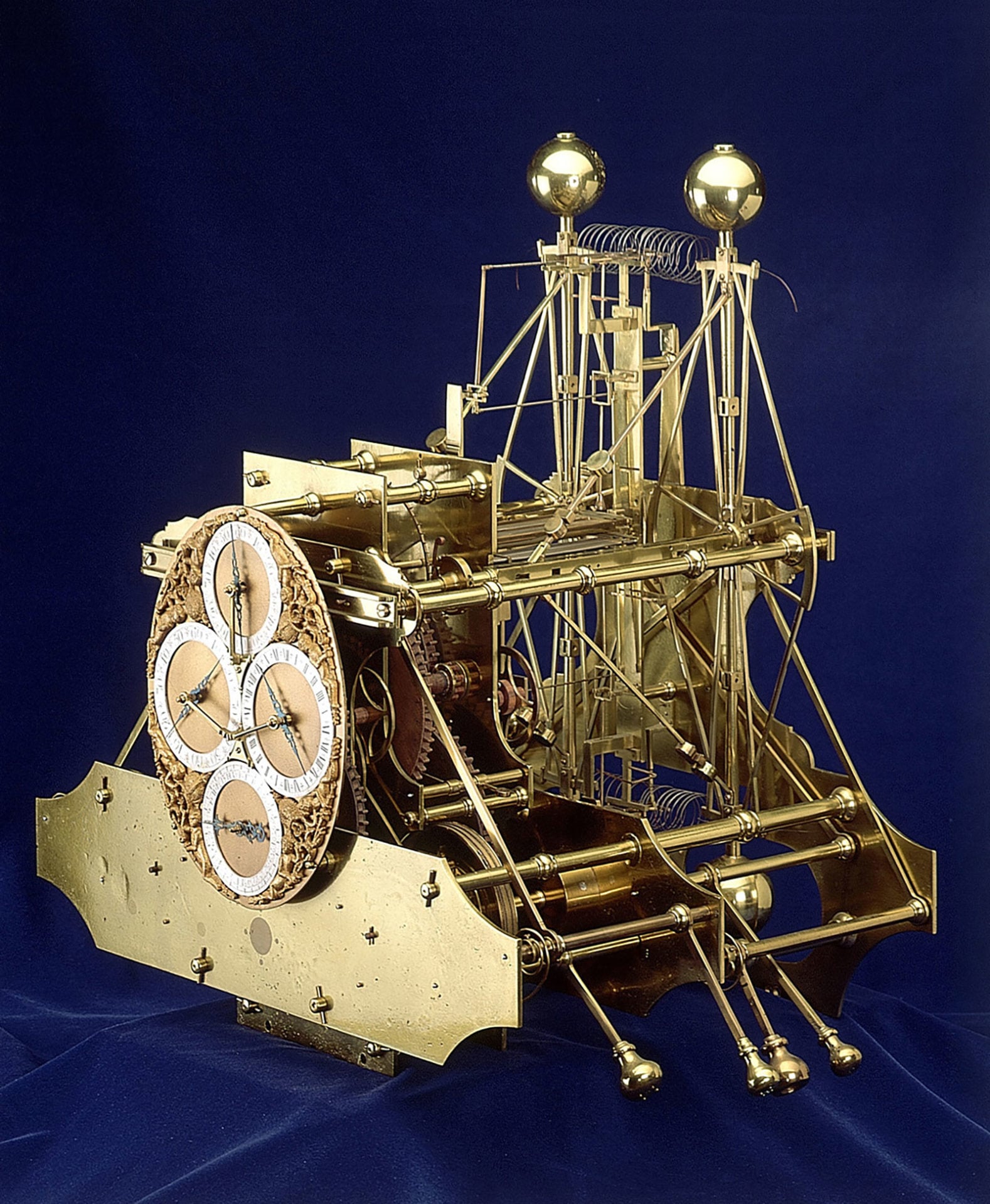

The distinctive design of H1 featured two prominent, bow-shaped pendulum structures at one end, each fitted with weighted spheres at both the top and bottom, and a clock face on the opposite end displaying hours, minutes, seconds, and the day of the month. Situated between these elements was a radically different horological mechanism, a framework of horizontal shafts and vertical plates, housing an array of wooden and brass gears, rollers, levers, springs and weighted arms.

Look closely, and the clarity and focus that Harrison brought to the problem is readily apparent: the clock is dominated by two large brass pendulums that move in opposition to each other, linked by coiled springs and crossing ribbons and designed to counter the influence of gravity on their oscillations – the pendulums would cancel each other out so negating the movement of the ship. There are mechanisms to compensate for temperature (through materials such as bimetallic strips and geometry), friction mitigation (such as the use of self-lubricating lignum vitae) and a system known as “maintaining power” to maintain drive (and hence, accurate timekeeping) during winding and, to crown it all, the Grasshopper escapement with its light-touch “springy” pallets that proved almost friction-free.

Bob Bray’s replica of John Harrison’s H1 Clock

Given the significance and innovation of the Harrison H1, it’s an obvious target for making a replica, and Sinclair Harding already had a reputation for its series of scaled-down and simplified H1 clocks before AHCI member, Bob Bray, bought the business in the 1990s (and moved it to his native Yorkshire just a few miles from where Harrison grew up). This project was going to be different in ambition and scope. The genesis was a conversation Bray had with Charlie Pragnell (the family-run business’s CEO) at the AHCI’s offshoot exhibition during Watches & Wonders in 2022, which led Bray to take on the challenge of building a full-size recreation as faithful as possible to the original. Easy enough, you would imagine, given that the original ticks away in the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.

Not so fast! H1 was a proof of concept, a prototype that was the start of a decades-long journey towards a sea-clock that was a truly practical and affordable solution to the Longitude problem. Not only that, but there are also no original drawings (the Longitude Board would later insist on drawings for H4) and the clock, which was acquired by the state in 1765, was then left to languish in a damp storeroom for eighty years before it was cleaned and was only restored to working order another 80 years later.

The clock is considered too delicate to be taken apart to the extent that Bray would have needed to simply replicate each component, so began a long process of direct observation, analysis of the drawings made by the amateur horologist RT Gould, who restored the clock in the 1920s and the work of other clockmakers to attempt the task of making replicas (each of which had errors). In the end, Bray had to test what was known about each of the more than 1,500 components against the design as a whole, looking to match the balance of mass and geometry that Harrison produced. You can get an idea of the task’s complexity from the wooden gears, which were complex feats of carpentry in their own right, with a single gear having 33 separate parts.

Intensive use of CAD models and state-of-the-art tooling helped Bray come closer than any of his predecessors to what is a quixotic challenge – Harrison himself is known to have tinkered with it while working on the later clocks, so there can be no truly pure replica. Where Charlie Pragnell and Bob Bray departed from the original is in its presentation. H1 would have been cased to protect it from the elements (and possibly prying eyes), where now the intention is to reveal the mechanism in all its glory, supported by a little theatre!

The Pragnell Bray Origins Clock is daunting in its size, mounted on a wooden hull modelled after HMS Centurion (the ship on which it sailed as part of the test) itself mounted on a table with an anchor pendulum that rocks the clock. The sight of the Origins clock at Pragnell’s Stratford-upon-Avon store is astonishing. The finish and detail are beyond reproach and hard to take in against the sheer presence of what was the most radical machine ever conceived in human history. It will star at a gala in Goldsmiths’ Hall to mark the 350th anniversary of the Royal Observatory, its permanent home not being settled yet. Pragnell have said that a limited number of commissions will be considered – I rather hope that an Atman, Heung or Musk would recognise the genius of the shy, if slightly grumpy, Yorkshireman whose conception it was.

More details about the Pragnell Bray Origins Clock at www.pragnell.co.uk.

1 response

Case size? Thickness? Power reserve? Price and availability?

j/k

Very cool. Will be delving into the site for more….