Discovering the Work of Chinese Indie Watchmaker Logan Kuan Rao

Coming from the Middle Kingdom, Logan Kuan Rao's watches are alomost entirely made by hand.

It’s not often we travel to China for stories on high-end mechanical watchmaking, even in the virtual sense. But, as the perception of watchmaking is shifting from Swiss dominion towards a more global industry, the Middle Kingdom has proven to be a unique source of rather interesting watches. Take Celadon HH, Qin Gan or Atelier Wen, for instance, who are determined to bring prestige to the “Made in China” designation. Today though, we’re uncovering another Chinese watchmaking gem by the name of Logan Kuan Rao. This self-taught indie watchmaker makes his watches almost entirely by himself and by hand. And as Logan Kuan Rao is about to deliver his second watch, the Wuwei, it was time to shine a light on this rising star.

Robin, MONOCHROME: Logan, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers?

Logan Kuan Rao: I am a watch enthusiast and, for the past ten years, have been teaching myself the art of watchmaking. I am from China, and I now have my own workshop in Guangzhou. I make almost all of the components of a watch from scratch, including the movement, dial, hands, and case, with only the mainspring, jewels, and shock absorbers being purchased. Because the entire watch is done under one roof by a single person, the equipment and methods I use differ from those of the mainstream Swiss watchmaking industry; therefore, the timepieces I produce are also somewhat different. I hope my work can add a touch of fresh interest to this age-old craft.

You’re originally from China, which is not typically associated with high-end artisanal watchmaking. Can you tell us something about watchmaking culture in China?

This is an excellent question. Historically, China predominantly adhered to a relatively singular mainstream perspective. In ancient China, the social elite cherished a grand narrative of their nation, often dismissing intricate craftsmanship as mere ‘????’, akin to carving small insects on a stone (meaning that they were insignificant or useless). Following World War II, China entered its socialist phase, during which timepieces were integrated into the planned economy, with the primary objective being the production of reliable and affordable watches in mega-large quantities, ensuring widespread accessibility so that everyone could wear a watch.

Given this historical and societal backdrop, there has been a notable absence of native high-end watchmaking in China. However, as this country has rapidly evolved and diversified, niche sectors like high-end watchmaking have begun to exhibit signs of growth. I am confident that in the future, we will witness the emergence of top-tier, distinctly Chinese independent watchmaking. At least, that’s a personal aspiration of mine.

How did you get into watchmaking? What sparked your interest?

I don’t have any watchmaking background. I studied Materials Science at Imperial College, London and Product Design at the Royal College of Art. In the beginning, I was simply a passionate watch enthusiast who liked to collect watches and discuss them with others on forums. As my knowledge and appreciation for horology deepened, my experience and taste evolved, and I began to focus more on collecting vintage watches and pocket watches. This journey eventually led me to become a moderator on China’s largest online watch forum.

One day I suddenly realised that the watch I longed for either didn’t exist in the market or came with an exorbitant price tag. It was at this point that I decided to venture into the world of watchmaking and craft the timepiece I had envisioned. This marked the beginning of an extensive and self-directed study into the art of watchmaking. I started buying tools around 2013, and I made my first prototype in 2016. However, it wasn’t until 2021 that I had optimised it to my satisfaction and officially delivered my first Orca.

Learning to make a watch is not easy. How did you start and select the necessary skills to do so?

Watchmaking was once a cutting-edge technology that was only mastered by a few people in a few countries. However, thanks to two centuries of technological advancement, it is now possible for one person to learn to make watches on their own. The skills required for watchmaking can be broadly categorised into two main areas: equipment operation and craftsmanship.

Equipment operation skills, crucial for watchmaking, have become more accessible due to the similarities with general precision machining techniques. The Internet and various learning resources offer a wide range of opportunities to acquire these skills. On the other hand, mastering craftsmanship skills is a process that demands repetition. To illustrate, although I managed to create a functional prototype in just three years, it took an additional five years of continuous practice to attain mastery over the remaining intricate techniques.

In summary, my knowledge of watchmaking primarily stems from online resources, books, and the invaluable experience gained through countless failures.

Where do you find the inspiration for your watches?

My approach may deviate from the mainstream. I don’t actively hunt for inspiration or ideas when it comes to designing a watch or a movement. The timepieces I’m presently developing and those on my future agenda are all born from ideas I’ve kept in mind for quite some time.

Your very first watch was the Orca, which you presented in 2017. Can you share how that watch came about?

As I mentioned earlier, I used to be a moderator on China’s largest online watch forum, where I frequently engaged in discussions with fellow watch aficionados. It was during these discussions that I noticed a common misnomer – the term ‘Côte de Genève’, often referred to as ‘Geneva waves’ due to the undulating reflection of Geneva stripes. This led me to ponder how I could transform the notion of Geneva waves into an actual representation of waves.

After careful consideration, I embarked on a creative journey by employing traditional watch movement finishing techniques to craft an image of “an orca leaping out of the sea.” To achieve this, I utilised anglage and loose-abrasive frosted surfaces to delineate the contours of the orca. Additionally, I incorporated perlage patterns to evoke the splashes, seamlessly transforming the Geneva stripes into the waves upon the sea surface.

It took quite some to deliver that first watch. What were your biggest challenges?

Yes, it took me three years to develop a working prototype of my watch and another five years to deliver the first one. As this year marks the sixth year, I am pleased to announce the completion of all nine pieces. I deeply apologise for the extended wait my customers endured, and their unwavering patience is a source of profound gratitude. Fortunately, I firmly believe that the final product surpasses the 2017 prototype in terms of refinement and cohesiveness.

For self-taught watchmakers, it is indeed a big challenge to make nine watches at a time. There are many parts to be made in a watch, and each part needs to be made nine times so that when I finished the last part, my skills and level were far higher than when I made the first part, so I made the first part again. In this way, time slowly passed. The biggest challenge throughout this journey was that “independent watchmaking lacks standardised solutions”. Many facets demanded personal exploration. You need to have a resilient mindset in the face of setbacks to ultimately achieve success.

The Orca watch was followed by the development of the Iceberg, with a patented Equal-Push escapement. Can you share some details on that one?

When discussing self-taught watchmaking, one name invariably stands out: George Daniels. And within the realm of his achievements, one term invariably stands out: Co-Axial Escapement. Geroge Daniels’ Co-Axial Escapement has been a successful innovation in the field of escapements. As a new entrant to the field, I am enthusiastic about contributing my efforts towards resolving this age-old conundrum of the escapement system, which has perplexed watchmakers for centuries. Therefore, I made some attempts.

The primary objective of the Equal-Push escapement was to introduce a joint lever to the co-axial escapement, enabling a more evenly distributed impulse force. I developed several prototypes, and their performance largely met my expectations, prompting me to file for a patent.

Nonetheless, I later came to realise that if I wished to make a timepiece that would showcase my invention through visible motion by the naked eye, I would need to enlarge every component and reduce the oscillation frequency. This adjustment, however, significantly affected its overall performance. Larger components carried greater inertia, and lower frequency caused greater instability. I grappled with the dilemma of choosing between an option that was “difficult to see by the naked eye yet highly functional” and one that was “visually appealing but principally less stable”. Consequently, I temporarily set aside this design. Presently, the timepieces I manufacture employ a Swiss lever escapement to a similar movement layout, which I’ve renamed Wuwei.

You do a lot of the work by yourself, by hand. Can you elaborate on that?

In China, there’s a timeless proverb, ‘????????’ (one’s character is shaped by the environment you inhabit). I believe that a similar principle applies to the world of watchmaking, where distinctive industrial contexts and cultural legacies give rise to varying styles among watchmakers and their timepieces.

Currently, within the realm of independent watchmaking, the Swiss manufacturing ecosystem and the Swiss aesthetic reign supreme. Nevertheless, there are still unique products in the market that showcase different styles, such as British, French, Japanese, or American. My approach to watchmaking, including the tools and techniques I employ, is contingent on the resources available in my specific environment.

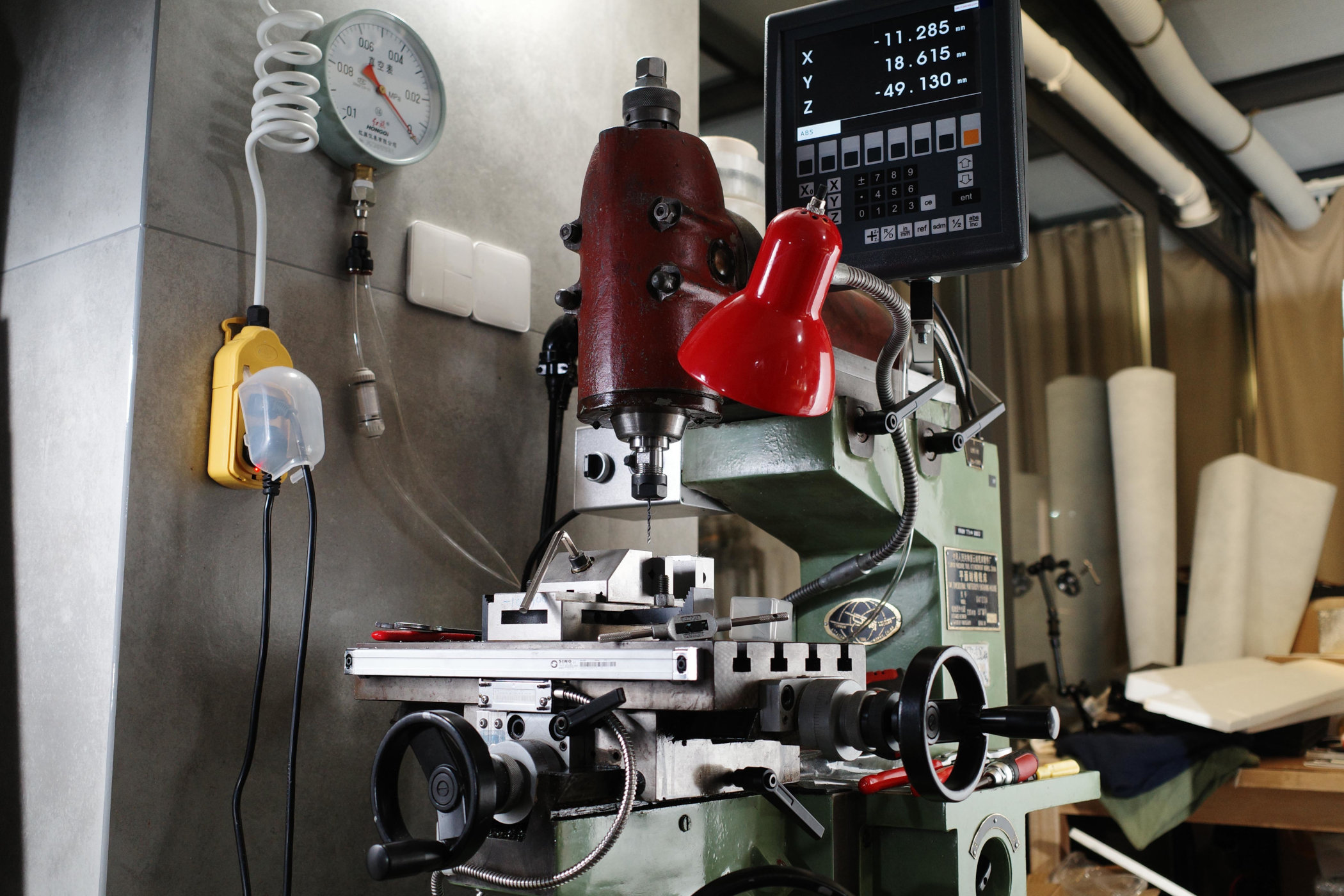

For instance, my toolkit includes a retired lathe from a radar manufacturing facility in Hefei, a milling machine modified from a pantograph originally used in an oxygen machine factory in Suzhou, and a CNC machine retrofitted from equipment that once belonged to Foxconn in Shenzhen. These devices, while possibly unconventional when viewed by Swiss counterparts have been modified by me to create timepieces that naturally possess a unique character. Independent watchmaking itself is a celebration of diversity, and my ability to craft components in-house forms the cornerstone of this diversity.

Do you base your movements on existing ebauches or design and build them from scratch?

When I first started working on the Orca, I didn’t have the machining capabilities to produce all the parts myself. I had to use some wheels that were made by a factory in Tianjin. As I continued to develop my skills, I eventually mastered the process of making wheels. This gave me the freedom to design and manufacture the Wuwei from scratch.

Can you tell us more about what to expect from you in the near future?

I have completed my first watch, Orca, and my second watch Wuwei is about to be delivered. I am currently working on a prototype of the third watch. Orca is a two-handed watch, and Wuwei is a three-handed watch. My next watch will have one more hand.

How can people get in touch with you to learn more about your watches and possibly order one?

My website is still under construction at the moment. In the meantime, you can stay updated with my latest posts and activities on Instagram. Also, feel free to reach out to me via email at [email protected]. I would be delighted to connect with you there.

2 responses

Thanks for the update on Logan’s work.

I like his work the closer you examine his work your thinking how did he do that? What is thinking out of the box.