The Chopard L.U.C 16/1860, One Of The Best-Kept Secrets in Neo-Vintage

And Chopard’s Rise As a Top-Tier Manufacture.

After a brief hiatus, we return to The Collector’s Corner, with an entry that is as far removed from the Omega Seamaster Professional 300M and the Rolex Explorer II Polar 16570 we last looked at, in both form and function. At Watches & Wonders 2022 (check out our full coverage here), Chopard presented not one, but three chiming watches to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the founding of the jeweller’s haute horlogerie ambitions under the L.U.C line. We thought it would thus be relevant to take a closer look at the beginnings of L.U.C and, more importantly, the groundbreaking movement powering it, the superb calibre 96.01… and of course, the ultra-desirable and elegant watches that came equipped with it.

The Calibre 96.01 was launched in 1996 as Chopard’s first in-house, automatic movement, and was developed over three years with a clear goal: establish Chopard as a serious contender was so forward-looking that its derivative movements still continue to power Chopard’s latest creations, like the Chopard Alpine Eagle Flying Tourbillon. When we talk about the characteristics that define a certain watch model or reference, we generally fall back on features like an iconic design, unparalleled legacy, and maybe even desirability and rarity. It is a rare watch that is defined by its movement: the Chopard L.U.C 16/1860 is one such watch.

A brief history of Chopard

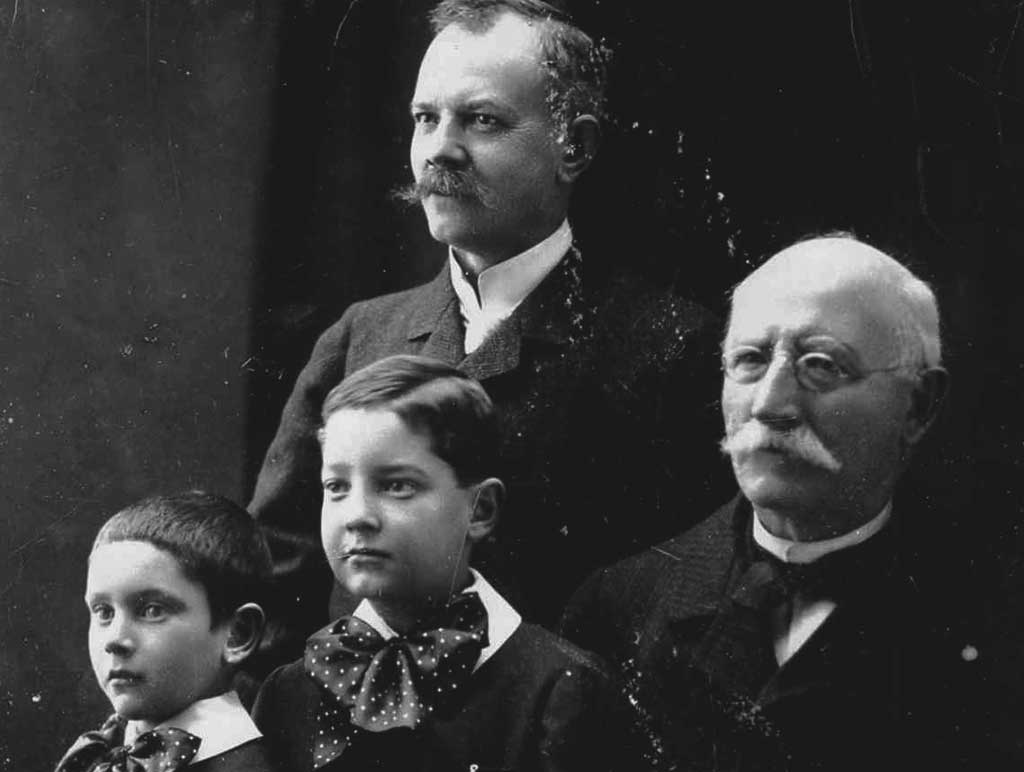

To understand the importance of the Calibre 96.01, we need to first take a look at the Chopard’s history. The son of a farmer, Louis-Ulysse Chopard founded his eponymous company in 1860. Chopard proved himself a talented watchmaker from the get-go, establishing his first workshop for the manufacture of pocket chronometers at the young age of 24. Chopard’s work quickly gained acclaim, with his watches praised for their reliability and accuracy. The quality of Chopard timepieces landed the young company two prestigious commissions, becoming the official provider of timepieces for the Tir Fédérale and the Swiss Railway Company.

These successes laid the foundation of the company his son took over upon the elder Chopard’s passing in 1915. The company headquarters were moved from Sonvilier, Switzerland to La-Chaux-de-Fonds, then to Geneva in 1937. War again came to Europe, severely impacting the demand for Chopard’s timepieces. The company, now in the third generation of family ownership in the hands of Paul-André Chopard, had managed to stay afloat to celebrate 100 years of existence, but Paul-André had begun to realize that a sale might be the only viable option to save the company.

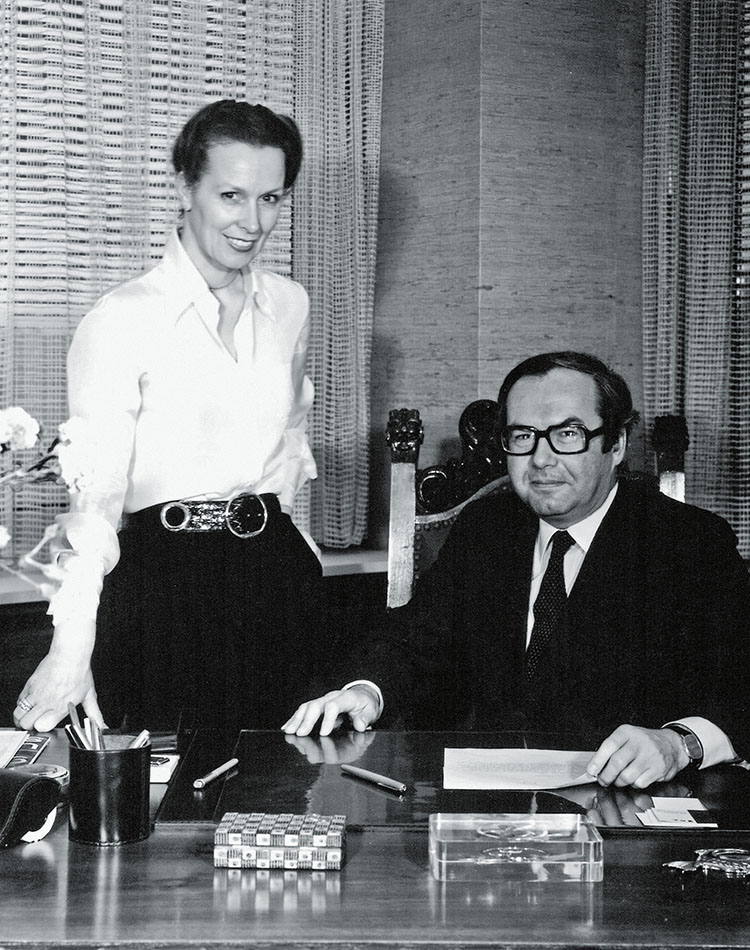

Enter Karl Scheufele III. Scheufele too was a third-generation businessman, heir to the ESZEHA jewellery company based in Pforzheim, Germany. Until then, ESZEHA had relied on third-party movements supplied by IWC, JLC, and Vacheron Constantin, but Scheufele wanted to bring the entire manufacturing process under one roof. In 1962, Scheufele was able to realize this dream when he and Paul-André Chopard agreed that Scheufele would assume ownership of Chopard.

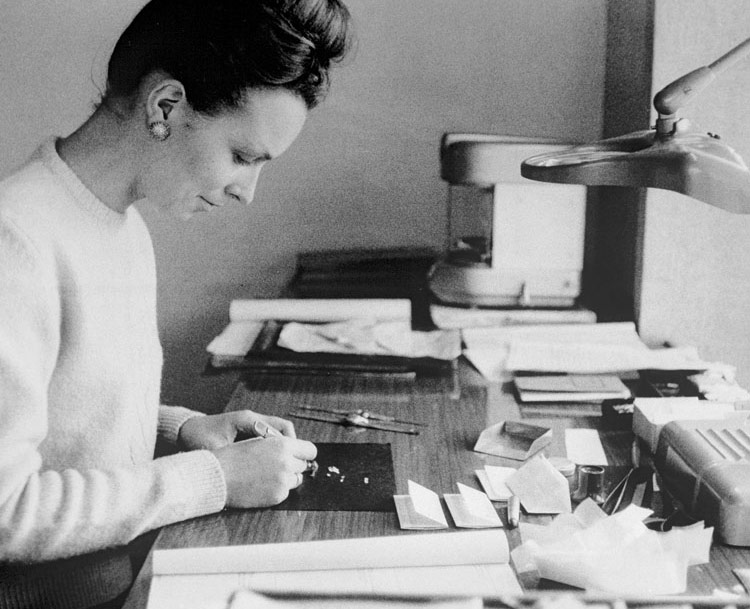

The quartz crisis led to a shift away from mechanical watches to low-cost, accurate quartz products. Scheufele knew that he could not win over customers on the traditional measures of quality like accuracy and reliability. He would have to pivot – drawing on expertise from the jewellery business, Chopard transformed its watch offering into just that: time-telling jewellery. This pivot led to the creation of Happy Diamonds, a collection that remains in the Chopard lineup to this day. Diamonds were sandwiched between two sapphire crystals but were otherwise free to move about on the dial. The concept was a hit!

Management of the Chopard company passed to Karl’s children in the 1980s, who became co-presidents. Caroline managed the women’s jewellery line, Karl-Friedrich was in charge of the brand’s men’s line and timepiece collection. The next milestone came in 1988, with the establishment of the Mille Miglia connection – Chopard became the official timekeeper for the famous race.

Throughout the quartz crisis, quartz watches were the bread and butter of Chopard’s watchmaking division. However, Karl-Friedrich had an ambitious plan: he wanted to return Chopard to its roots as a manufacture of mechanical watches. Scheufele took a gambit in 1993, setting up a team in the town of Fleurier with the goal of developing an in-house calibre. The team was given carte blanche, and three years later, the automatic calibre L.U.C 96.01 was born, named after the founder Louis-Ulysse Chopard.

The Chopard L.U.C 16/1860 – The basics

First, a note on reference numbers. The 16/1860 family consists of three references: the first inaugural reference 16/1860/1 is equipped with a hunter-style caseback and was produced in only 100 examples before being discontinued and replaced by the 16/1860/2. The 16/1860/2 did away with the hunter caseback (allegedly due to issues with the hinged caseback on the previous reference) but otherwise shared the same dial and movement, namely the Geneva Seal Calibre 96.1. The reference 16/1860 (note the absence of the final specifier), was a more accessible watch built around the similar, if less elaborately finished Caliber 3.96 – I will go into the differences below. The 16/1860 reference also lacks the engine-turned dial that makes the “/1” and “/2” references so desirable.

After the turn of the century, the L.U.C Tonneau 16/2267 was released in 2001, with a shaped movement designed around the 96.01 (the movement was called the 6.96). The Tonneau featured the same dial details as the 16/1860/1 and 16/1860/2, though the guilloché central dial was stamped rather than engine turned. Other rare references include the 17/1860/2, which features the same specs and Geneva Seal movement as the 16/1860/2, but has a bezel set with brilliant-cut diamonds – fitting for a jewellery house!

It’s customary for me to start this section off with a description of the case, the dial, and the wear of the watch we are discussing before I move on to the technical specs. However, I think it’s only fair for me to turn this order on its head this time. Why? It is rare that a watch movement gains as much recognition as the watch itself – movements of comparable stature include the Jaeger-LeCoultre 920 or the Patek Phillipe Calibers 12-600 AT or 240. Enter the Chopard L.U.C Calibre 1.96.

Conceived together with Michel Parmigiani (founder of the eponymous Parmigiani Fleurier brand), the Calibre 1.96 took around three years to develop, with completion in 1996. The brief for Parmigiani was simple: to make a thin, modern, and highly decorated automatic calibre that would cement Chopard’s place among other top-tier watchmakers in Switzerland. One year later, the calibre made its debut in the reference 16/1860/1.

Let’s start with the base specs: the calibre 1.96 is a 3.3mm thin automatic movement with a solid power reserve of 65-70 hours. Bidirectional automatic winding was achieved with a fully jewelled, pawl-based rocker system. As a concept, it resembles the IWC Pellaton winding system – as the rotor oscillates, its movement is transferred to a pawl (basically a toothed beak), which drives the ratchet wheel, in turn winding the mainspring. For more pictures of the automatic system – and of the 1.96 in general – I refer you to the fantastic technical write-up of Walt Odets, who, at the time his article was published in 2002, wrote that “the calibre 1.96 is probably the finest automatic movement being produced in Switzerland today.”

The impressive power reserve is thanks to Chopard’s “twin” technology, namely two stacked barrels operating in series. The use of two barrels not only endows the watch with a healthy power reserve, but also with impressive timekeeping. Truly, this was the movement’s trump card – the 1.96 was one of the rare Geneva Seal calibres to undergo COSC certification. So proud was the manufacture of this feat that both the chronometer certificate and the paper form of the Geneva Seal were delivered with each watch.

Isochronomism was further enhanced by the use of a Breguet overcoil hairspring (flat hairspring in 3.96 and later generations) and a swan’s neck fine adjustment regulator. Oh, and of course, the seconds hack, because what use is an accurate movement if you cannot set it to the precise second?

The finishing of the Calibre 1.96 is absolutely exemplary, with each screw and jewel countersink being finely polished. Every bridge has mirrored, rounded anglage that was clearly performed by hand. All screws are bevelled on their circumference and slots. Even the swan’s neck regulator – a fine and thin spring is bevelled on its edges. Every surface of every component has been removed of machining marks and decorated with polish, brushing, solarization, or Côtes de Genève.

Some interesting tidbits about the caliber 1.96 and later generations:

- The Calibre 1.96 runs on 29 functional jewels. Early versions of the calibre, both on the 16/1860/1 and 16/1860/2 references are 32-jewel movements, though it is believed that these are merely decorative.

- The Calibre 1.96 cased in white metals were equipped with a platinum PT950 microrotor, as opposed to the 22k yellow gold rotor found in YG and RG models

- The first numeral in the caliber name refers to the generation of the movement, the suffix “96” to the movement family. Thus, 96 is the microrotor automatic family, 98 the 9-day Quattro family. Chopard’s movement naming convention was later modified and the order inverted, thus the 1.96 became the 96.01, the 3.96 became the 96.03, and so on.

- All 1.96 calibres have a billowing guilloché pattern cut on the automatic winding rotor. There are versions of the 3.96 with the same pattern, but also those with a hobnail pattern. The pattern likely correlates to the material of the rotor (see point below), as rotors with a hobnail pattern do not have a visible “22k” hallmark.

- Early 3.96 rotors were made of a heavier base metal (tungsten) capped with 22k gold. These were later replaced with solid 22k rotors – the same as in the caliber 1.96

- Another differentiation between the 1.96 and the 3.96 is the use of a kidney-shaped stud holder (black-polished, of course) in the 1.96 due to the requirements of the Geneval Seal.

Seen from head-on, the reference 16/1860 is what you would sketch if I asked you to draw the quintessential dress watch. Precious metal? Check. Small seconds? Check. Details that impress as you get closer? Check, check, and check.

The references share features found on some of the most enduring dress watches of our time, such as the Philippe Dufour Simplicity or the Patek Philippe Calatrava. The watch is classically sized, at 37mm in diameter, with a case in yellow gold (silver and black dial variants), rose gold (silver and black dial variants), white gold (silver, blue, and salmon dial variants) and platinum (silver dial variant). The dial is a study in classicism. Starting from the outside and working our way in, there is a brushed track with dashes for the minutes. Slightly inboard is a sunken track with a radial brushing that acts as the hour track – the hours are marked with applied yellow gold arrowhead hour indices. There is a double index at 12.

In the “/1” and “/2” references, the centre of the dial features a hand-laid billowing soleil guilloché pattern radiating out from the cannon pinion. Set in this central dial, just below the 12 o’clock markers, the brand name is printed on a “plaque” that has also been cut into the solid gold dial blank. Now, this is where it gets even better: these guilloché dials were manufactured by Metalem SA, a dial manufacturer based in Le Locle, Switzerland, that gained publicity for producing the dials for the Dufour Simplicity. No wonder the two watches look like they were cut from the same cloth!

As is traditional for dress watches, seconds are displayed on a subdial – with both brushed and concentric patterns. A small concession to practicality has been made in the form of the date window, which has been set within the sub-seconds. The hour and minutes hands are dauphine in shape and are half-polished, half-frosted; the seconds hand is a simple baton style with a counterweight.

Coming to the case, you notice that it too is classical in style and construction: the three-part case is entirely polished. The caseband makes up most of the volume of the case from the side – set slightly back from the caseback, the bezel is domed in a fashion that harks back to pocket watches. The caseback is secured with eight screws.

Alongside the hallmarks stamped into the metal, the hunter caseback in the “/1” was engraved with the words “Chopard Manufacture” and a beehive – the symbol chosen by the founder of the manufacture.

Why you should consider the Chopard L.U.C 16/1860 and its calibre 1.96?

I am guessing I have your attention by now! There are quite a few reasons why I decided to dedicate an episode of The Collector’s Corner to the 16/1860. First off, the looks: I have a weakness for classically-styled, elegant dress watches. The 16/1860 knocks this one out of the park and can easily compete with the traditional players in this space. The versions with Metalem dials are a wonder to behold and have clearly been executed sparing no expense. If I had one niggle, it would be the date window, but I can’t deny its usefulness. Also, the window itself has been executed well, with a step down instead of a mere cutout. Also, props to Chopard for deciding to use matching date wheels – the salmon dial and salmon date wheel combination is particularly lovely.

The second reason is the movement. Though the 16/1860 was not met with the greatest commercial success, its movement was widely lauded. In each of its guises, the 96 family of movements is a technical powerhouse and still is a bit of a sleeper movement. Micro-rotor automatics are slowly becoming more and more accessible as materials technology makes them more efficient and more robust, but in the early 2000s, that was most certainly not the case. The movement is also quite a looker regardless of the variant. Of course, the 96.01 takes the cake, and I believe it to be one of the most beautiful automatic calibres in existence.

The last reason is that there are many different variants of watches carrying the calibre 96 family to choose from, spanning the whole gamut of budgets. Perception is everything in the world of luxury, and it is fair to say that outside of our niche community, Chopard is still widely thought of as a jewellery house first and as a watch manufacture second. What this means is that the calibre 96-based watches were for the longest time trading at a considerable discount and only started to gain recognition in the last three years.

At the top of the lot is the 16/1860/1 – these rarely come up for sale and are also the rarest – followed by the 16/1860/2. Expect to pay upwards of 20-25k Euros for the references with Metalem dials. The rarest of these, in platinum, or white gold with a blue or salmon dial, will certainly command a premium. Given the state of the market, I would not be surprised to see an asking price of above 30k.

Next on the price hierarchy is the 16/1860, which currently trades between 5-7k Euros. Rare dial variants will likely command a premium – expect to pay around 9k-11k Euros. The price differential compared to the reference 16/1860/2 is substantial and these, though not inexpensive, are an outright steal in comparison. The Calibre 96.03 is not stamped with the Geneva Seal, but is not in any way a detuned movement, as it is still chronometer certified and has the same power reserve.

And finally, we come to the Chopard L.U.C Sport, powered by the calibre 4.96. This is the steel, sports-watch equivalent to the classical 16/1860. The L.U.C Sport can be had with a dark blue dial or silver dial, both with machine stamped guilloché dial. L.U.C. The 4.96 movement lacks hacking seconds but gains centre seconds and a more traditional date positioning at 3 o’clock. Of the three references so far, this is probably the best as a daily driver – at 10mm thick, it retains an incredibly slim profile and is incredibly comfortable on the wrist. Despite the svelte proportions, the watch is endowed with 100 meters of water resistance, and the entirely brushed stainless steel case makes it a fantastic all-rounder. Think of the L.U.C Sport as a high horology competitor to the Rolex Explorer, but for half the price. I know which one I would choose! I should mention, for the sake of completeness, that the L.U.C Sport was preceded by the Pro One of 2004, which was Chopard’s first manufacture calibre sports watch and was powered by a calibre 4.96.

No matter which way you go, however, I doubt that you will end up regretting your decision. These are all terrific references, and all helped to lay the foundation for the rise of Chopard and of L.U.C.

Illustration images for this article were provided by mrwatchley.com and are used under prior agreement.

9 responses

Great article, enjoyed it immensely. 🙂

I saw this 16/1860 model live in yellow gold. Although yellow gold is not my preference, this watch was gorgeous. If I had to choose from all the watches I have ever seen in my life, one model that would be the essence of elegance, it is this watch. A beautiful piece.

Let me tell you a secret: 16/1860/1 Stop being a secret a long time ago…

If this caliber had been used into Alpine Eagle at their first release appearance (non-tourbillon), it would have been a perfect combination in competing with VC Overseas and AP RO on the same table…

Very interesting article. I was fascinated by an artcicle about happy diamonds and immediately bought one for my wife who use it every day leaving a rolex in the drawer?

Thanks for the excellent article about the history and merits of the L.U.C 16/1860. I particularly love the limit edition L.U.C XPS 1860 Officer released in recent years, first in white gold with silver dial three years ago and then in yellow gold with green dial announced in W&W last month.

Love the straps. Is there a name for that style, that type of leather?

They are epsom leather straps. Love to know who makes the black/charcoal with dark stiching

Big post, good read