The History of the Iconic Calibre 11 (and its Evolution)

Dubois-Dépraz celebrates the 50th anniversary of one of the first automatic chronograph movements.

1969 was a revolutionary year for watchmaking with the advent of the automatic chronograph with three distinct projects presented almost simultaneously. Fifty years down the line, Zenith has been celebrating the 50th anniversary of the El Primero with great fanfare, Seiko commemorates 50 years of automatic chronographs, and TAG Heuer pays tribute to its 50-year icon, the Monaco. It is now time for Dubois-Dépraz to pay tribute to a movement that powered some of the most iconic sports chronographs: the Calibre 11 or Chronomatic.

The first wrist chronographs appeared in the early 20th century but these were powered with hand-wound movements for years. In the 1960s, watchmakers embarked on a genuine race to develop the first self-winding chronograph. Three parties started to develop their own projects, each with its own merits and its own technical vision.

- Zenith with the code-named 3019 PHC calibre, better known as the El Primero – The development of this high-frequency integrated chronograph was initiated in 1962 with the goal of presenting the movement in 1965 to coincide with the centenary of the brand. The calibre was also named “Datron HS 36” at Movado, which commercialized the movement under the Zenith-Movado-Mondia consortium.

- Seiko with the calibre 6139, a 27mm integrated, column-wheel chronograph with vertical coupling and beating at 3Hz.

- The Chronomatic/project 99 Consortium uniting Heuer-Léonidas SA, Léon Breitling SA, Hamilton-Büren and chronograph specialist Dépraz & Co. This joint-venture conceived the Calibre 11 (or Chronomatic, depending on the brand using the movement), a modular construction based on a micro-rotor Buren movement and a Dépraz chronograph mechanism.

The Chronomatic consortium and Project 99

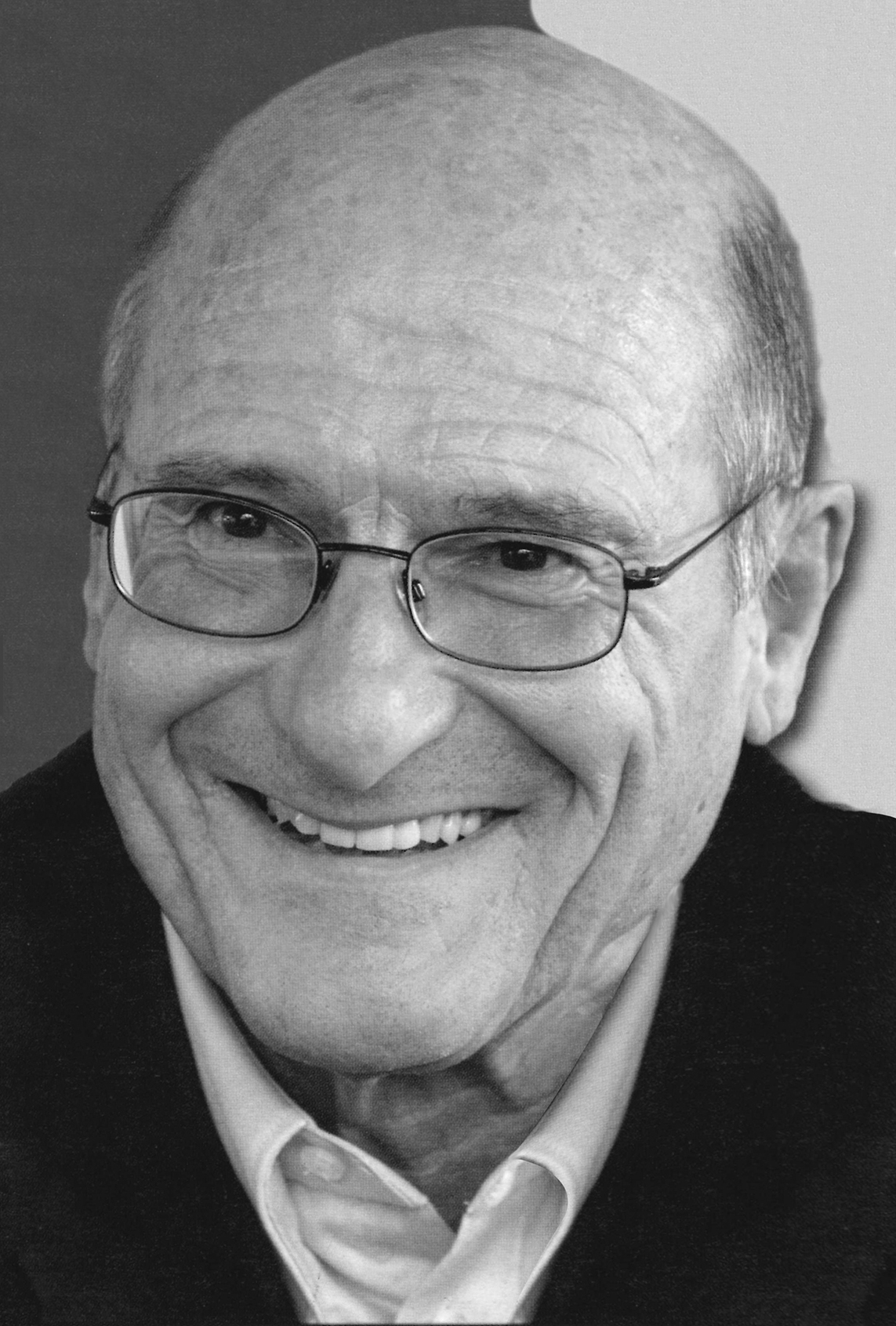

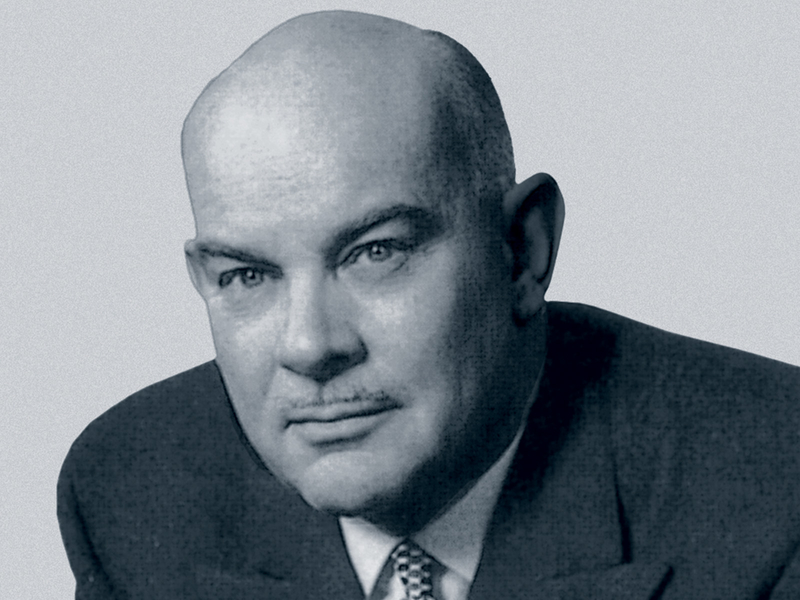

Above: Gerald Dubois, Hans Kocher, Jack Heuer and Willy Breitling

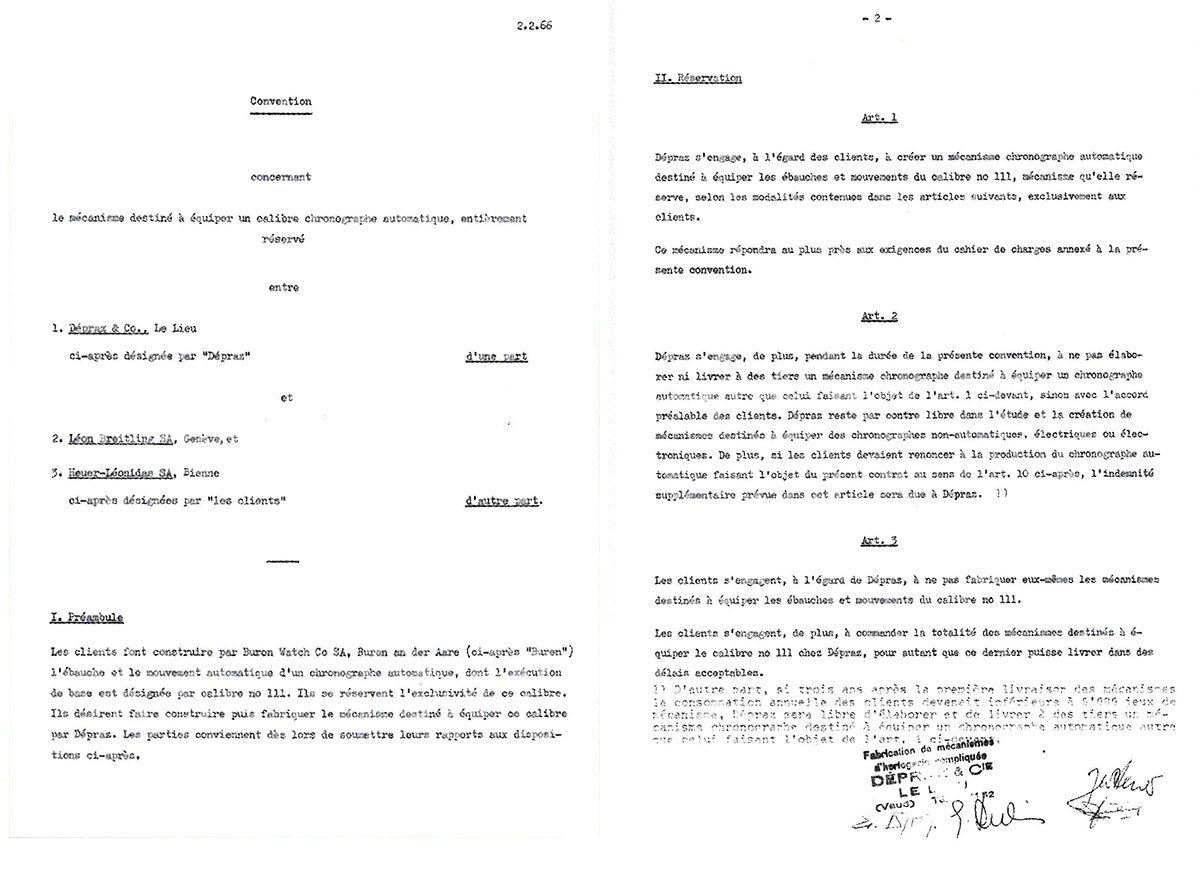

The history of the Calibre 11 starts at the end of 1965. As Büren had pioneered the production of micro-rotor movements, Gérald Dubois (of Dépraz & Co., a chronograph specialist) figured out that these would be thin enough to be the base for a modular chronograph movement. Dubois contacts Hans Kocher of Büren Watch Co. SA. In need of commercial partners, they manage to convince first Jack Heuer and then Willy Breitling to support the project. On February 2nd, 1966, an agreement is signed. The four-party Chronomatic consortium is born, including two rival brands teaming up to develop their own automatic chronograph. For confidentiality purposes, the development is code-named Project 99.

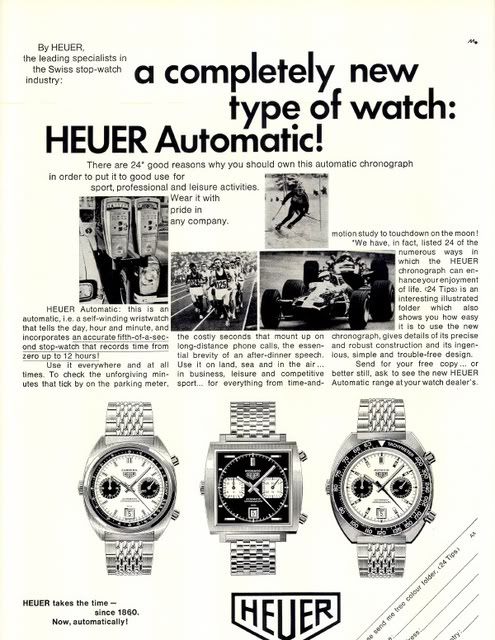

Büren is in charge of the base calibre. Dépraz of the chronograph mechanism. Three brands – Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton (who acquired Buren during the development process) – will fit the movement inside their watches. A patent application for the Calibre 11 is filed in September 1967. At the end of 1968, about 100 pre-production movements are assembled in prevision of the 1969 Basel fair. On March 3rd 1969, the movement is officially presented, simultaneously in New York and Geneva. A month later, the three brands present their first chronographs at the 1969 Basel fair. With the practicality and comfort of automatic winding, the chronograph becomes a staple of motorsport… the Calibre 11 is used to power iconic watches by Heuer (Carrera, Monaco, Autavia), Breitling (Chrono-Matic) and Hamilton (Fontainebleau). And later by other brands such as Bulova, Kelek, Zodiac, Elgin, Stowa…

So, who won the race?

Zenith’s automatic chronograph was the first to be unveiled to the world. It was presented during a press conference in January 1969 and christened El Primero (“the first” in Spanish). The reality is a bit more complex. There are endless debates about which was the first automatic chronograph, as both the Seiko and the Chronomatic movements were announced later the same year. What’s more, El Primero was not the first to hit the market. But the controversy about who came first doesn’t really matter anymore… what is important is the impact that these movements had on watchmaking history. Since then, the automatic chronograph has remained one of the most popular complications.

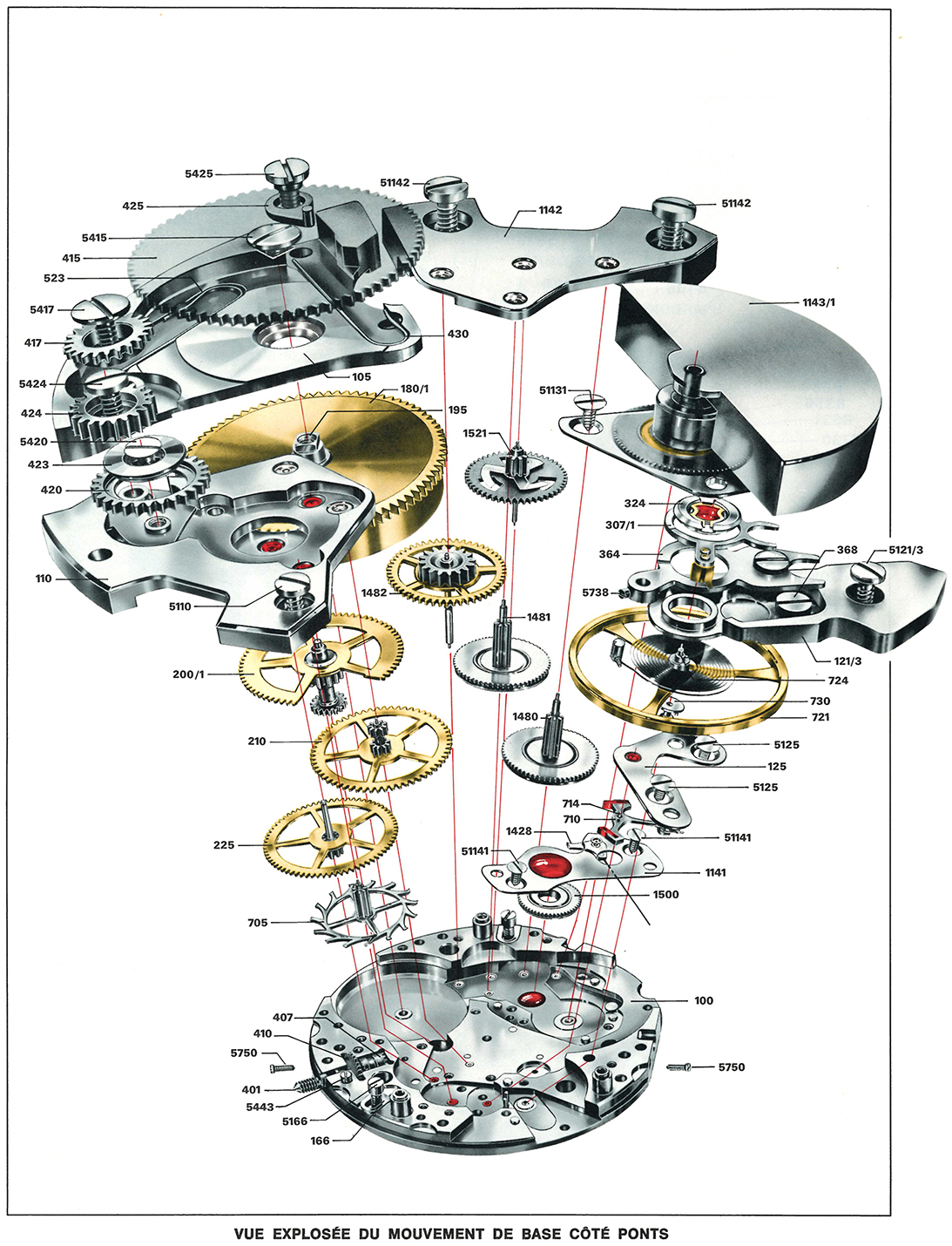

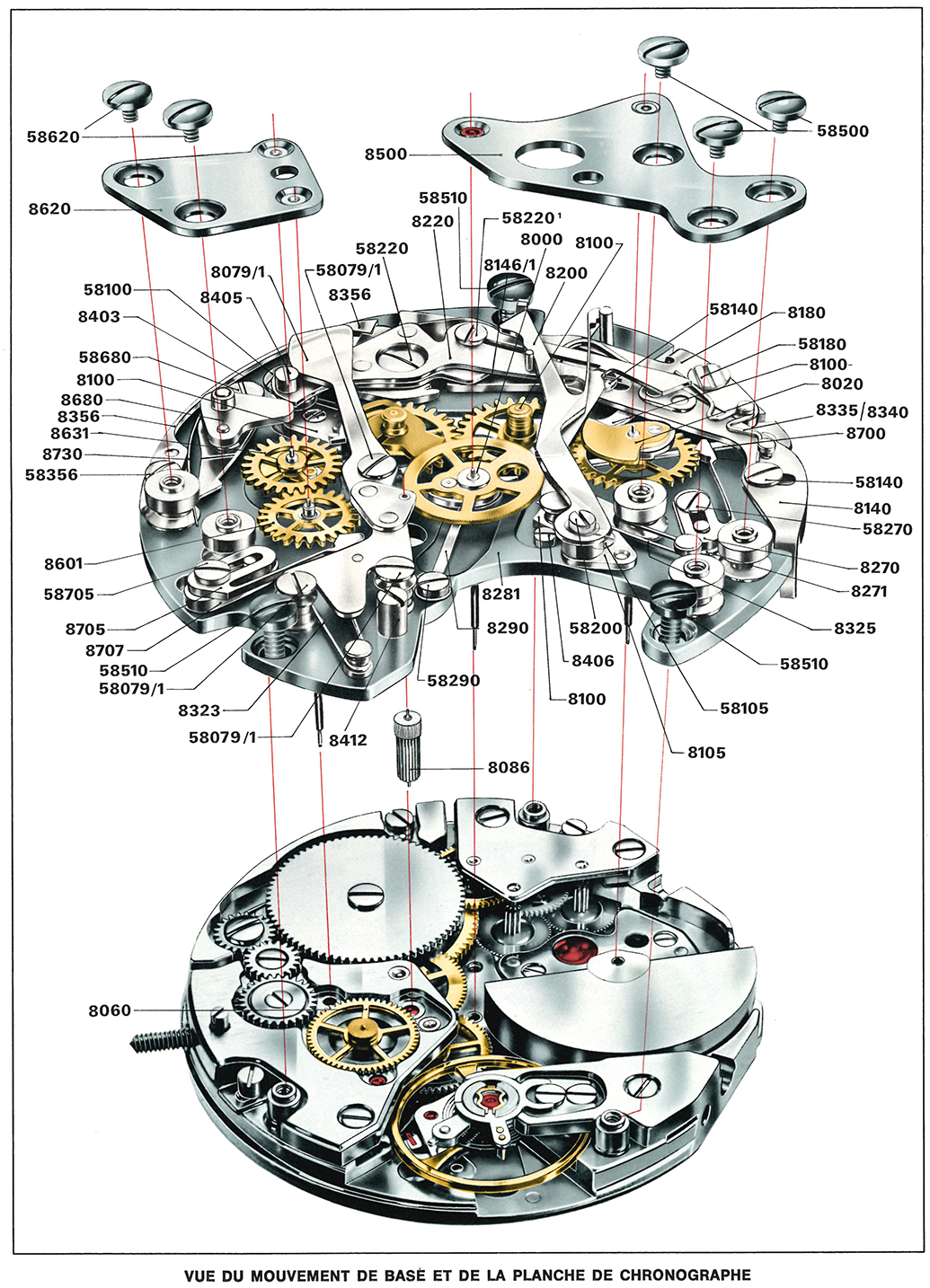

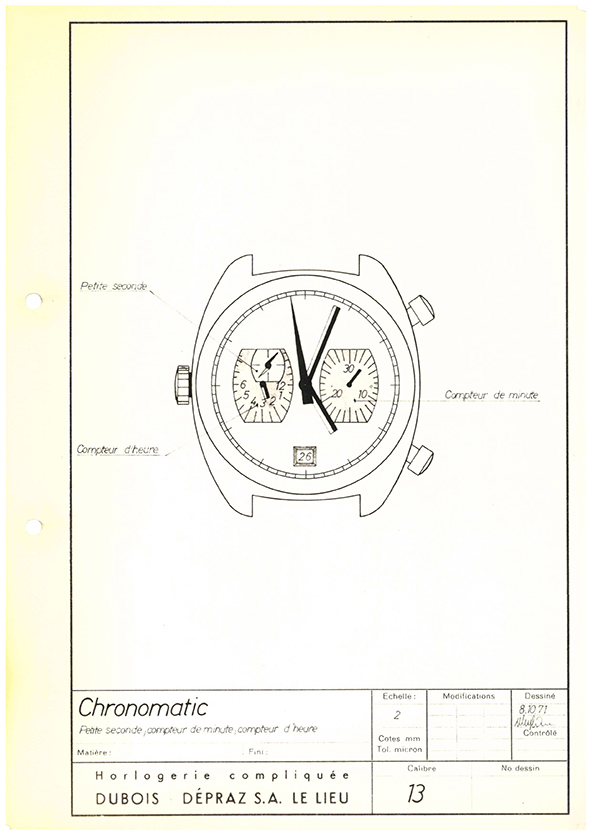

The Calibre 11

The Calibre 11 is a 17-jewel modular chronograph measuring 31mm x 7.7mm. This modular architecture implies first a base movement, a micro-rotor automatic calibre made by Büren, in charge of the timekeeping part. Beating at 19,800 vibrations per hour, it boasted 42 hours of power reserve. Manufactured by Dépraz, the lever chronograph module is assembled on the backside of the base movement. This movement has a bi-compax display, with a 30-minute counter at 3 o’clock and a 12-hour counter at 9 o’clock – no running seconds sub-dial. The date is indicated at 6 o’clock. The unusual crown position, at 9 o’clock at the opposite of the chronograph pushers, is a signature feature of the movement.

The Calibre 11 and its evolutions

Like most movements, the Calibre 11 has been optimized several times over its lifetime. As early as 1969, a barrel spring providing less torque is used. The date jump mechanism is adapted. The sliding pinion is changed and made in steel.

In 1971, a variant running at 21,600 vibrations per hour and named Calibre 12 is introduced. It becomes the main product of the calibre family. It uses a stronger barrel spring. The gear train and balance wheel are adapted. The chronograph hammer is modified to improve shock-resistance.

The Calibre 13 is developed to integrate a small seconds indication in the periphery of the hour counter but will never be commercialized. In 1972, the Calibre 14 adds a GMT function and the Calibre 15 adds a small seconds to the Calibre 12, positioned at 10 o’clock, replacing the elapsed hours sub-counter.

In 1974, a new movement, the Calibre 7740, is launched. This movement features the same display and the same functions as the Calibre 12 since the chronograph module is identical. However, it relies on a different base calibre. Manufactured by Valjoux, it is now hand-wound, it runs at 28,800 vibrations per hour and the winding crown is classically positioned at 3 o’clock. It is used, among other watches, in the last versions of the Heuer Monaco, such as the PVD-coated “Dark Lord”. This movement will also be the last one to use this specific chronograph module.

For more information, about Dubois-Dépraz, you can read our introductory article about the company and their new integrated chronograph movement here.

3 responses

Very interesting, thank you!

Awesome read, learnt a lot

Interesting that you have a portion called ‘Who won the race’ but you don’t actually say who won the race and even propose ‘who came first doesn’t really matter anymore’, when it does actually matter. Perhaps this is because it was the Seiko launched first with the Speedtimer featuring the calibre 6139 in May 1969, the Zenith launching in October of the same year. I’m not entirely sure how this is perceived to be embarrassing enough for the Swiss watch industry to mask all these years later but its not controversial, merely historical fact.