An Ode to a Timeless Classic: The IWC Mark Series

Most of you have probably heard about the IWC Pilot’s Watch Mark XVII. This is the latest incarnation of IWC’s classic line of pilots’ watches with a central hour, minute, and second hand and a date function. In this presentation we are going way back in time in order to trace its bloodline, which is one of the most important in the history of horology. The Mark series of watches were created as life saving tools for aviators, designed in accordance with military specifications and nowadays have reached a cult status that few wristwatches attain.

At the start of the 20th Century, mankind began to make its first endeavors to conquer the skies. The time-keeping apparatus was an essential tool that progressed in parallel evolution with aviation and those first attempts towards proper navigation in the air.

Leading the development of the early navigation wristwatches was Prof. Philip Weems of the U.S Naval Academy and the “Seconds-setting” watch that he designed which was produced by Longines in 1929. Later, in 1932, Longines again used the input of the great Charles Lindbergh to produce the “Hour Angle” model. (See our previous article: The History of the Pilot Watch Part 4 – Longines and Lindbergh). These two models, were the archetypal aviation watches that ultimately led to the development of a vast array of dedicated aviation timepieces, with some of the most famous belonging to the Mark family and the B-Uhr family (see our previous article: The History of the Pilot Watch Part Five: B-Uhr) of Aviation/Pilot/Navigator watches. The Mark series in particular, are considered to be among the most iconic bloodlines of purpose built timepieces in the history of horology.

History and evolution of the Mark Series

The Early models (IX – X)

From the earliest advent of flight, keeping track of time was an absolutely crucial element of the whole operation. The aviators had to deal with vibrations, extreme temperatures, variable light conditions and most importantly powerful magnetic fields. The watches that existed in those early days were not designed to withstand all of these conditions. The first watch from IWC specifically designed for Aviators was the originator of the Mark series, produced in 1936. The Spezialuhr für Flieger (Special Pilot’s Watch) had a black dial, high contrast luminous hands, and a rotating bezel which helped its user to measure elapsed time accurately up to one hour. It was of course a hand-wound timepiece, with the caliber 83, being shock-resistant and tested and adjusted at extreme temperatures. This specific model was one of the pioneers of the timepieces that we identify today as aviator watches, and it became known as the Mark IX. It is important to point out that it was never labelled by IWC as a Mark IX. Its name derived colloquially the next model,which was classified as a Mark X by the British MoD (Ministry of Defense).

In the early 1940s the British compiled a set of specifications for military watches that they wanted to supply to their troops. The twelve companies that produced watches which were accepted by the MoD as meeting these specifications, would later become known among collectors as the dirty dozen: Buren, Cyma, Eterna, Grana, Jaeger LeCoultre, Lemania, Longines, IWC, Omega, Record, Timor and Vertex. The Mark X name was adopted by all the manufacturers and in 1944 the IWC Mark X was issued to the military for service. It had the caliber 83 as well, and it was signed with the Broad-arrow or Pheon (which denotes property of the British Crown) and the three letters W.W.W (Watch. Wrist. Waterproof). For 4 years it was used by a variety of military personnel including RAF pilots and navigators. However the real start of the mark family came in 1948 with the model that perhaps created and helped to sustain the legend of the IWC aviation timepieces.

The mark series mature (XI-XII-XV)

The Mark XI is considered by many collectors to be one of the finest military watches ever produced. The XI entered service in 1949, having been specifically built in order to help the RAF navigators during their dead reckoning duties. For the personnel of that time a chronometer and a sextant were adequate in order to calculate latitude and longitude. The MoD put out requirements for a navigation timekeeping wristwatch, that would have a highly accurate movement with hack-device, an inner soft iron cage forming a shield to protect the movement from magnetic interference, a stainless steel waterproof case with a screwed ring in order to protect the crystal from sudden decrease of pressure, and a black dial with luminous hands. The XI was introduced into the RAF (Royal Air Force) and the FAA (Fleet Air Arm) in 1949 and into the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) in 1950. At first IWC and JLC (Jaeger Le Coultre) provided the watches, however having bought 2,000 XI’s from JLC the RAF decided to buy only from IWC (up to 1953). The tests these watches passed in order to be declared ‘fit’ for active service were quite demanding.

Upon delivery, the MkXI was subjected to an exhaustive 44-day testing period for ‘Navigator Wrist Watches’. Each batch, then had to be sent to the chronometer workshop of the Royal Greenwich observatory in Herstmonceux. All watches had to be sent there from active units for maintenance as well. These, ‘fitness’ tests entailed a 14-day period rating in 5 positions and at least two temperatures, plus further tests for ensuring the antimagnetic and waterproof properties of each piece. After passing these tests, each watch marked for a 12 month interval were the tests had to be run again. The Mark XI was originally reserved for use only by navigators while later on it was issued to pilots as well.

Although the last XI was delivered to the RAF in 1953 the type was not officially decommissioned untill 1981. IWC actually sold watches, in the open market, though its commercial network (around 1,000 pieces) while XI’s were still been given to pilots and navigators of the BOAC (British Overseas Airways Corporation). The watch was rather small and unassuming by today’s standards (36mm in diameter) and it was equipped with three hands and no date display. It was driven by the IWC caliber 89, which is generally considered one of the greatest movements ever produced. The caliber ran at 18,000 bph and was equipped with a barrel bedded at both ends, a patented drive for the central seconds hand, and a Breguet hair spring. Precision and reliability were the key descriptors for this fine piece of micro-engineering.

The replacement of this legendary wristwatch came in 1993 when IWC introduced the Mark XII. It maintained the 36mm diameter and similar styling throughout but featured the addition of a date window, and, for the first time, an automatic movement. Interestingly, it was a Jaeger LeCoultre caliber 889/2 that was used as a base for the IWC caliber 884/2. The well-reputed movement had 36 jewels and ran at 28,800 beats per hour. As Michael Friedberg, moderator of IWC’s ‘in-house’ forum, wrote in an article in 2000, “The Mark XII is more than a watch; it is an homage to the tradition of fine Swiss watchmaking. It salutes military watches; it salutes flight watches and it salutes the heritage of International Watch Company… In some ways, the Mark XII is the ordinary watch par excellence’“.

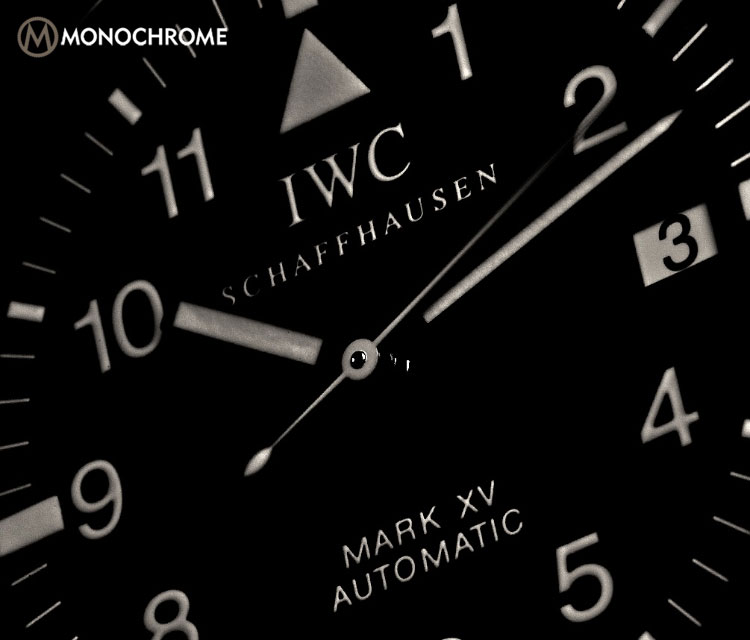

Through the Mark XII the precision military aviation timekeeper transformed into an austere and classy civilian wristwatch; this metamorphosis was completed with the 1999 introduction of the Mark XV, the model we photographed for this article. The peculiar thing someone might notice and wonder about is, why name it the 15 instead of 13 or 14? The rationale was purely due to superstition. The number 13 is considered unlucky in the U.S and Europe while the number 14 is shunned for similar reasons in Asia.

The XV introduced two radical changes. Firstly it grew bigger (38mm) and secondly instead of a JLC movement, it used a caliber 37524 from IWC which was based on the ETA 2892-A2 movement. In all other aspects it was a spitting image of its predecessor, the MkXII. While the first change was welcomed by collectors and buyers the second one was not so well received. For the first time a member of the legendary Mark family had not a JLC movement but an ‘ordinary’ ETA. However, this was far from an ordinary caliber (28,800 bph with 40-hour power reserve). IWC’s changes to the base movement were such that you could almost describe it as a total revision. According to official statements, the factory bought the top version of the 2892-A2 (chronometer version) and then proceeded to replace all critical components along the path from the escapement to the mainspring. The caliber was gold plated and adjusted in 5 positions and at least 2 temperatures, sticking with the tradition of the family. This was the end of the traditionally styled Mark model because in 2006, IWC introduced its revised successor.

The ‘New Mark’ (XVI-XVII)

In that year, IWC decided to update its entire Pilot’s collection by giving them a more unified look. The Mark XVI adopted the flieger hands of the Big Pilot’s Watch which were longer and wider in order to better fit the larger dials and cases. The watch grew by 1mm while the dial changed font; the numerals 6 and 9 were also omitted. The XVI used the IWC 30110.cal (based on the 2892-A2) while it kept the antimagnetic and waterproof qualities of its predecessors. The crown’s characteristically small fish emblem (to indicate water resistance) also changed to a ‘Probus Scafusia’ stamp. Although a radically revamped model, and one that was not received well by the traditionalist fans of the Mark series watches, the XVI kept many of its family’s inherent qualities while also becoming fresher and more modern. Its production ceased in 2012 when the Mark XVII (see here) was introduced.

Epilogue

In the history of wristwatches, few designs have been more archetypal than the remarkable IWC Mark family. These wristwatches were created for the specific needs of a special breed of professionals, the aviators. They have remained in production from 1936 until today. A large portion of their design character was dictated by purely military requirements, hence mottos like “Form follows Function” & “Less is more” find their true meaning in these watches.

Through the years the Mark wristwatch progressed from strictly a military styled tool to a watch that managed to keep its austere design qualities but also become a highly desirable wristwatch in the market. Either a modern or a vintage Mark timepiece would be the perfect everyday companion, which IWC obviously has understood, since they have revised it and offered many variations in their catalog throughout the years. Just check out the Mark XII for SAAB and Mark XVII Special Edition “Le Petit Prince” that IWC introduced last year.

From the point of its inception to the present day, the Mark has managed, like no other, to be associated with the aviator watch and nowadays it is classified, deservedly so, as one of the most important and influential timepieces in history.

16 responses

Hi Ilias,

Great read. Just two things.

The calibre 89 in the Mark XI is IWC’s own calibe, not from JLC.

The name ‘Mark X’ is not the original name. The watch was ordered by the Army (not the Air Force!) as W.W.W. (Watch Wrist Waterproof). The name Mark X was given by collectors afterwards. There were 12 other manufacturers for this watch.

Source: IWC Engineering Time since 1868 by Fritz’, Coelho and Bilal, p. 245-248

Bas

Hi Bas,

Glad you liked the article.

Regarding your first point. Yeap, that was a typo error and will be fixed.

Regarding your second point. I quote from the article.

“Its name derived colloquially the next model,which was classified as a Mark X by the British MoD (Ministry of Defense).”

Also

” …… The twelve companies that produced watches which were accepted by the MoD as meeting these specifications, would later become known among collectors as the dirty dozen…The Mark X name was adopted by all the manufacturers and in 1944 the IWC Mark X was issued to the military for service….. For 4 years it was used by a variety of military personnel including RAF pilots and navigators. ”

Cheers

Ilias

Another fine article that brims with information about a truly iconic timepiece.

Nicely executed job Mr Yiannopoulos.

Excellent article, thank you. Precisely the reason I purchased a mkXV around the time of this article. It is the last faithful representation of an icon.

Whilst I don’t mind the XVI, the ‘altimeter’ style date window on the XVIi seems to show a trend toward gimmicks for IWC which is disappointing for a brand with genuine history.

Unfortunately I don’t have the wrists to pull off a 46mm big pilot!

I found a IWC mkxv automatic in the goodwill in excellent condition for $10. Wondering if it’s authentic and it’s value. Any advice?

Can you send us a photo of the actual watch?

Well told article, however be careful as my Mk XV pilots watch which worked beautifully when first purchased was sent of for it’s twelve month guarantee service at an accredited IWC service centre. When it came back it did not run on time and would not auto wind , even on an automatic watch winder. After consulting with the original seller a very reputable established firm they advised me that IWC would look at the watch, however, it was going to cost about half of the original cost to have it sent off to Switzerland to be serviced. I deemed this to be a bit rich, so after trying two local watch (and I hesitate to say) repairers I found a watch repair craftsman who at one time did repair work for Rolex specialists in the Bulington Arcade, London. He for A$350 gave the watch a service which included a new (IWC) mainspring and showed me two pieces of broken bezel glass that were found inside and had bent the escapement and caused problems. He did warn me that genuine spares will be harder to get in the future as IWC has brought all servicing to in house. The repairer did warn me that the fine tolerances of the watch makes a normal watch winder not good enough to keep the watch fully wound when not being worn (his winder in his workshop looks more like a scale model of a sideshow fun ride). So unless I wear the watch sixteen hours a day I have to manually wind the watch, until the next service when I hope he can do something about that. Problem is that good watch repairers with IWC experience are thin on the ground in Adelaide. But, after all the watch is accurate to minus 5/10 seconds a day and is otherwise a delight to be it’s owner.

Where can I get a strap like that?

Really? Twenty (count them yourself….20!!!) photos of the dial- but not one of the movement?

@Bill Nopper: the Mark XV (like most Mark series) has a closed case-back

I bought my Mark XV in 1999 from a very well known watch retailer in L.A.

I had three watches at the time, and wanted to simplify my life and minimize my watch collection. I had been experimenting with collecting watches for a year or two, but by no means did I have any real expertise in timepieces, or horology. My collection included a Rolex TBird, a Two Tone Datejust, and a Patek Calatrava.

I’d had the Patek for 12-14 years, but though beautiful in 18k it was a bit formal for a contractor. I loved the classic and clean look of the TBird (less so for the 2Tone), and never would have sold it except for the fact that I found both the Rolexes and their steel bands quite uncomfortable.

Living in L.A. my whole life, I had perhaps passed by this one retailer’s store not less than a thousand times. But this time, I decided to stop in and pay them a visit.

I was searching for a quality timepiece with the simplest face I could find. The salesman pointed me immediately to a new IWC XII with a leather strap. One look – even before trying one on – and I was hooked.

However, once I tried on the XII, the deployment strap fit my wrist poorly. The salesman then showed me the XV with a steel strap. That steel strap, with its mesh design, fit like it was made for my wrist. The XV was larger and heavier than any watch I owned, or had ever owned, but it felt nearly weightless on my wrist.

Ironically, the XV was quite a bit less expensive than the XII, so it was a no-brainer. I went home with it. (Within a few weeks I had sold off my other watches, fetching a nice premium over the price I’d paid. Full disclosure: Although I am not a purveyor or retailer of any kind, I have sold something like a dozen watches over a period of years, and have never had a complaint about one that I’d sold.)

Sometime after I’d bought the XV, I learned that the XII was a more valuable than the XV, and more sought after as a classic. Nevertheless,I’ve never regretted buying the XV. First, and foremost it’s a watch – not jewelry – which fits my wrist better than the XII. And with its larger size, it fit my eye better, too. (Moreover, to equip the XII with a steel strap would have cost a small fortune.)

When I bought the XV, the salesman told me to: 1) never open the case, 2) never swim with it, and finally, 3) don’t service it until it stops. The first two admonitions were probably good advice (from everything I’ve read since), but the third was, unfortunately, not a very good piece of advice.

When the watch did stop, I brought it back the retailer for repair, thinking that their sizable service department would certainly have expert watch repair for my model, and would probably save me quite of bit of money, too.

That was a mistake, or rather, two .

After two years, the watch still didn’t run more than a day or so before grinding to a halt. After all that, I extracted a promise from the retailer that if after one last attempt at repair it still didn’t run properly, he would ship it off to IWC for repair.

As they say, good on him and good to his word, he did send it to IWC. Finally, it was expertly serviced. Sadly for the retailer, IWC charged him twice what he had charged me. Waiting so long – until the watch completely stopped running – had dried out all the lubrication, and all that friction had destroyed the watch’s internals. IWC essentially replaced the entire movement, along with the crown and crystal.

(I’ve posted about this experience before, so I’m not mentioning the dealer’s name because, ultimately they’ve done right by me, and are, in other respects, imo, honorable.)

Again, years later, I waited until the watch began to run poorly – but not stopped – before returning it for repair. This time I went directly to the IWC store in L.A. (actually Beverly Hills): The new repair from IWC wascostly, but generally in line based upon the value of the watch, the service performed, and period of operation.

This time, the cherry on top was when IWC returned the watch to me and I opened the box. I was stunned to find that the watch had been utterly transformed from a well-worn watch to a brand new timepiece.

I was told that IWC’s method of scratch and nick removal is so precise and effective, it completely restores the watch to “new.” As a semi- retired contractor I am no longer on the “line” daily, so three years later, my Mark XV is still nearly flawless. I say “nearly,” though my naked eye cannot perceive any imperfections in its appearance. There is neither a nick nor scratch on the crystal, case, bezel, nor anywhere on the bracelet or clasp. And, btw, I was not charged a red cent for the latter improvement.

Nearly twenty years on, my IWC Mark XV still fits beautifully; and though rugged and masculine, it’s still beautiful to my eye. I can’t imagine that in my lifetime I will ever need, nor wear, another watch.

Vincenzo, your story is beautiful. I would like to share it on the IWC forum.

I have own an IWC Mark XV, for the last 3 years, wore it in a daily basis, it gains about 3 seconds per day, better than most well known watches such as Rolex, etc.. I think it is the best watch in every respect that I have ever wore. Congratulations to Vincenzo on the very well writen article.

Jose Casas

Do you happen to remember where you got that Nato strap from?

Very nicely written article. I enjoy my MkXV immensly.

@flokon, which of the nato straps in all the photos are you referring to?

I have both XV and XVI. The XVI was my grail watch, and ten years after I first saw it, I managed to fulfill my dream. A few years later, I became somewhat annoyed by its size. It was a bit too large for me. I decided to switch to the XV, and since then, I wear it for 80% of the year. It is outstanding in terms of both wearability and versatility. It is a default tool watch (black dial with a low-profile font for numbering and a contrasting date window), but it has this spark of elegance that was missing until the Mark XX.

Furthermore, once I learned that the XVI and subsequent Marks have luftwaffe hands, I felt somewhat embarrassed wearing it. I am aware that the history of the brand is complicated, and that this might be somewhat irrational, but rationality and collecting watches usually do not go hand-in-hand.

Either way, great article. The picture at the top of the paper is the best picture of this watch I have ever seen. It perfectly captures the charm of it.