How Watch Dials Are Illuminated?

From radioactive and dangerous radium to Grade X2 Super-LumiNova, watchmakers have experimented with lighting dials at night for over a century.

Technology has overshadowed some of the advancements of watch dial lume that have progressed for over a century. For example, the digits on Hamilton’s Pulsar P1 LED watch from the early 1970s were bright by the nature of the tech – light-emitting diodes. Timex introduced INDIGLO back in the early 1990s, which provides a bright, uniform backlight with the push of a button. And who can forget the tiny “light bulb” in 1980s LCD watches from Casio, Seiko and others that lit up from one side with an uneven, barely adequate glow (it was cool at the time). Smartwatches have always-on screens (as do smartphones), while just about every clock in your house and car is self-illuminated (from the oven to the microwave to the dashboard).

Mechanical watches have seen a huge resurgence since the Quartz Crisis of the 1970s and 1980s, and dial lume has never been better. It’s brighter, longer lasting, and there’s a wide assortment of colours, all without batteries. For those of us who prefer tradition and all things mechanical, dial lume remains a huge part of the watch-wearing experience. It’s not just for general nighttime visibility – divers rely on lume in dark water, cave explorers rely on it in underground caverns, and then there’s dark movie theatres and even just showing off with a UV flashlight. Since the dawn of the 20th century, watch dials and lume have gone together like New Year’s Eve and champagne. Not a requirement, but a very desirable combination.

Radium

Radium was discovered in 1898 by scientists and married couple Marie and Pierre Curie. Marie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in 1903 (she won a second in 1911), while Pierre shared that 1903 prize for achievements with radioactivity. It wasn’t all sunshine and roses as both suffered from radiation sickness following the discovery of both radium and polonium, and Marie died in the mid-1930s from aplastic anaemia as a result (Pierre was killed in an unrelated accident in 1906). It wasn’t until 1902 that newly discovered radium glowed when W.J. Hammer mixed radium with zinc sulfide, and a paint derived from this mixture began appearing on watch dials in 1908.

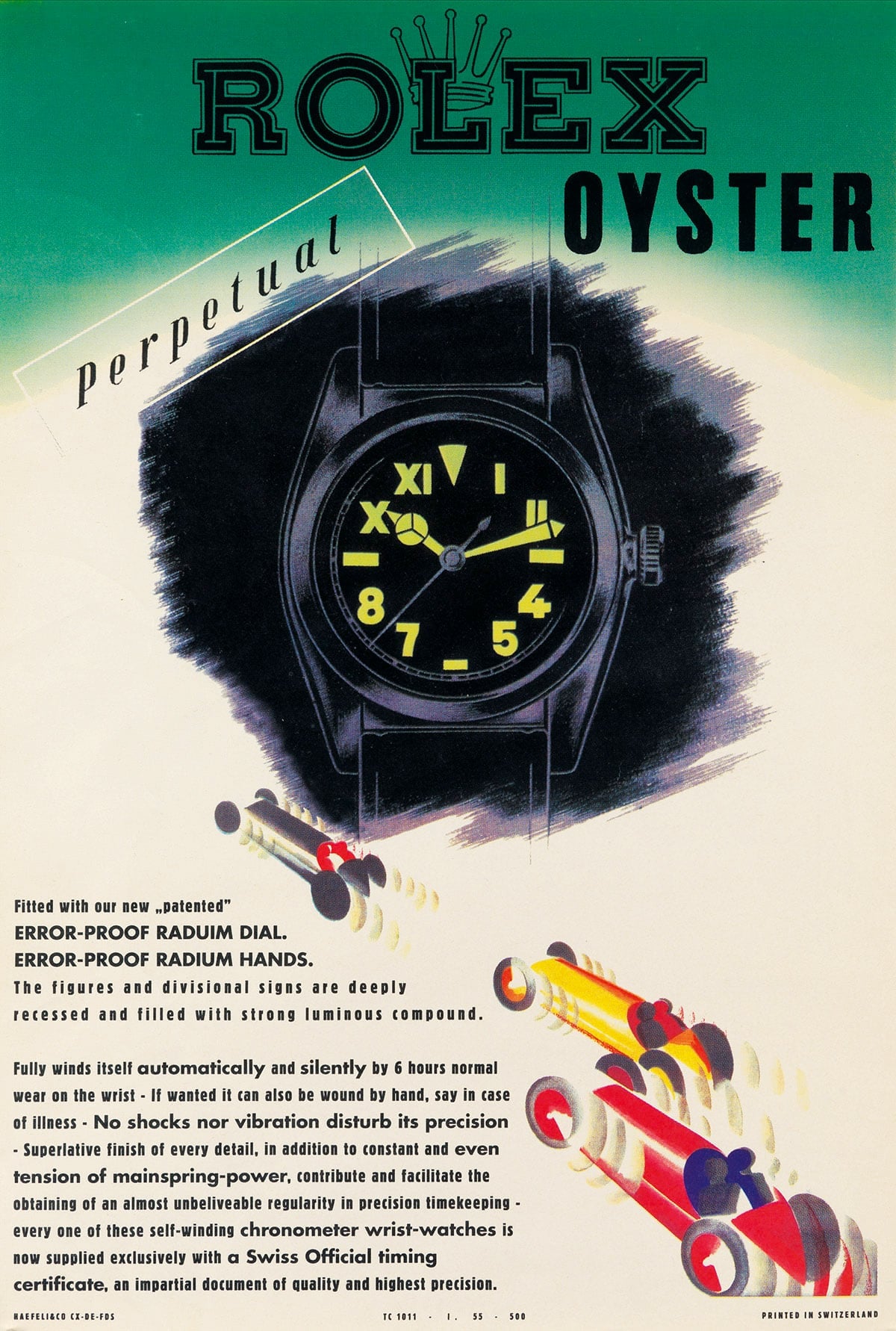

This was a game-changer at the time, as dial elements could clearly be seen at night with this magical paint that always glowed. It went mainstream in 1914 after the Radium Luminous Material Corporation was founded by Dr Sabin Arnold von Sochocky and Dr George S. Willis, leading to mass production of “Undark” lume. The Radiolite pocket watch from accessible watchmaker Ingersoll became a huge hit in 1916, bringing radium to a wide consumer audience and setting a standard for watch dials moving forward. It was an industry sensation and played a significant role in World War I as radium became a requirement for soldiers’ trench watches for nighttime visibility (without requiring external light that could compromise positions). Unlike modern lume, radioactive radium always glowed without needing to be charged by light. The most common glow was green from the zinc sulfide, but some mixtures were tweaked for a blue or even red glow; those were rare. It was all just perfect, until…

The Radium Girls

Our understanding of radiation was limited at the time, particularly the dangers (although industry leaders had a clue – see below), and young women were hired in the 1910s to paint radium on watch and clock dials. It was believed that women, by nature, were more talented with the delicate and precise dial work. This soon became a “patriotic duty” as military trench watches were in high demand. For such precision, the brushes needed to have a fine point, so the women were instructed to use their tongue and lips to continuously maintain the bristles’ pointed shape. This exposed their mouths to highly radioactive material, which was also ingested in significant amounts over time. The body confused radium with calcium, so it accumulated in bones and caused necrosis or “radium jaw” – teeth fell out, jaws started to rot, bones fractured easily, and anaemia, cancer and death often followed. Industry leaders were quick to deny any relation between radium and the chronic illnesses, blaming anything and everything from X-rays to poor diets. The truth was more sinister as most understood the growing dangers, at least in part, and ignored them for profit and efficiency.

In an era when women’s rights were lacking, a group of these Radium Girls sued the US Radium Corporation in the late 1920s (the new name for the Radium Luminous Material Corporation) and ultimately prevailed, as there was no denying the horrific symptoms. This was a major win that set labour safety precedents that continue today. Government agencies like OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) eventually formed as a result of enforcing new safety standards in the workplace, from construction to factories to farming. Given all of this, however, radium remained the watch industry’s lume until the 1960s as the dangers still weren’t clearly understood, and the benefits (at the time) outweighed the risks. New and intact watches released small but consistent amounts of gamma radiation – low yet still a potential cancer risk over time. As radium paint begins to deteriorate on the dial over the years, airborne alpha radiation particles can escape through bad seals and be inhaled. And storing radium watches in a drawer or even a closed closet can cause radon gas to build up as radium decays, which is a dangerous carcinogenic gas known to cause lung cancer.

Rolex responded to the growing concerns in the late 1950s by recalling the GMT-Master (ref. 6542) with radium-coated Bakelite bezels (that were also contaminated with Strontium-90), replacing them with aluminium counterparts. The few surviving ref. 6542 models with intact Bakelite bezels are now highly collectable as a result. There was also a lawsuit in 1961 from U.S. Navy veteran Willard M. Mound, who claimed to have health problems from wearing the model. The US banned the use of radium on watch dials and bezels entirely in 1968, but major watchmakers were proactive and removed the radioactive lume earlier – Rolex and Omega replaced radium with tritium by 1963, for example. The rise of the atomic age in the 1950s and 1960s also highlighted radiation dangers to the public, who demanded change.

Tritium

Tritium is also a radioactive lume, but safer than radium and poses little risk to watch owners with its low-level beta radiation (compared to gamma radiation from radium). Tritium was discovered in 1934 by physicists Ernest Rutherford, Mark Oliphant, and Paul Harteck, but it couldn’t be effectively isolated from hydrogen isotopes until 1939 (tritium is Hydrogen-3). Its use as a luminescent material was patented by Edward Shapiro in 1953 and made it to watch dials about a decade later. It glowed from the material’s beta radiation reacting with zinc sulfide in the paint – the same general process used with radium’s more dangerous gamma radiation. These dials had designations at the bottom to confirm the new use of tritium, like T SWISS T or SWISS T<25. Tritium wasn’t perfect, however, as its effective half-life was around 12 years, so it faded over time. Tritium was also used for radiometric dating and even to help boost nuclear explosions, but it’s best known as the watch industry’s lume standard from the 1960s through the 1990s.

Tritium Tubes

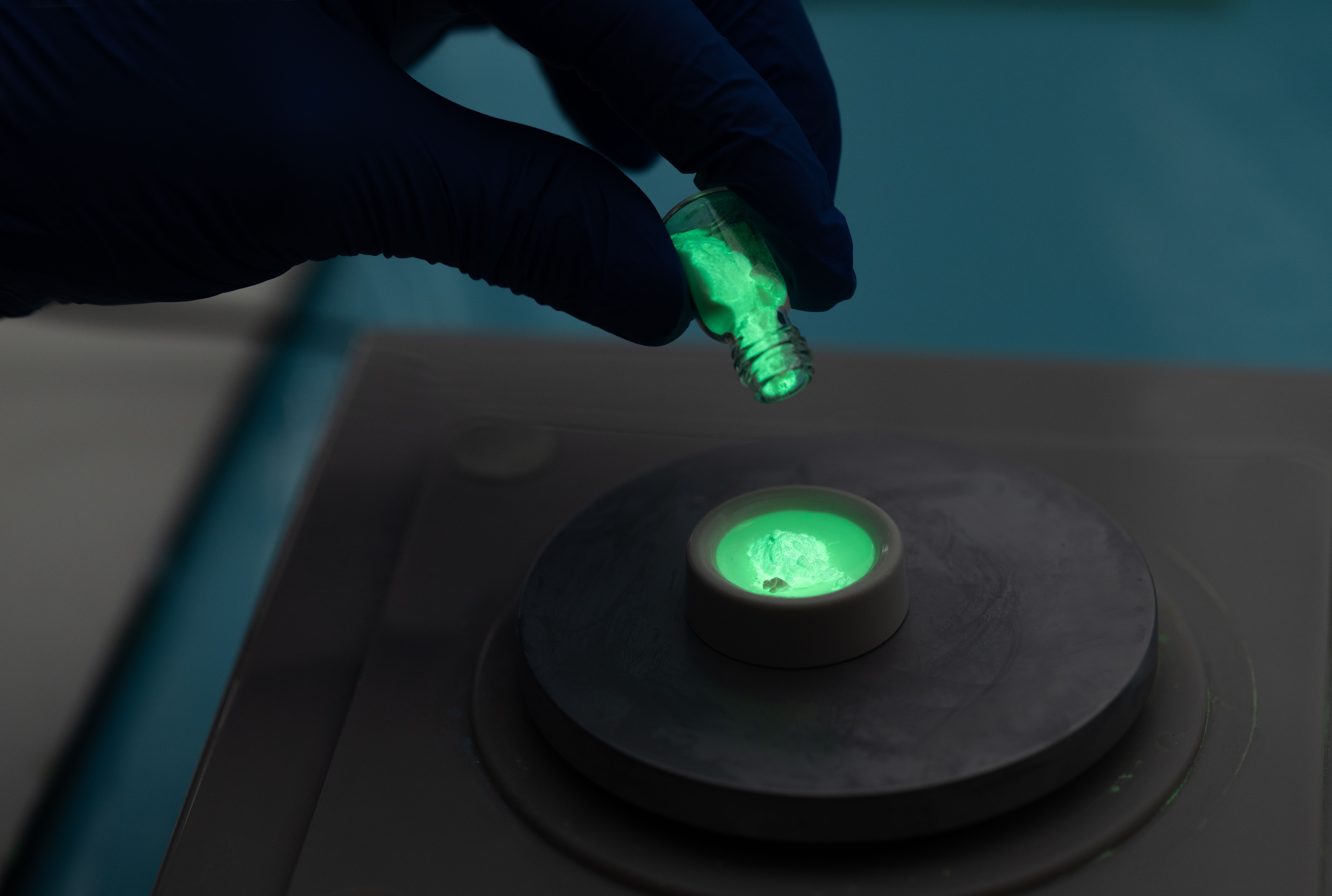

An improved albeit rarer form of tritium on watch dials is tritium tubes, and they’re even popular today. Instead of paint mixed with tritium and zinc sulfide, tiny glass vials are sealed with tritium gas and a powdered phosphorescent coating, which creates a continuous glow for up to 25 years without the need for external light for a charge. The tubes are brighter and more reliable than tritium paint and pose virtually no risk from the sealed radioactive material. The overall method is similar to the paint counterpart, as beta particles in the tritium gas react with the internal phosphor coating (in the same way as zinc sulfide). The tubes are known as Gaseous Tritium Light Sources (GTLS), and Ball Watch Company is a true GTLS pioneer and among the first to embrace these gas tubes.

The Ball Roadmaster M Model A is a great example with tritium tube indices and Arabic numerals at 12, 6 and 9 o’clock formed by a series of tubes. Luminox (with “Luminox Light Technology”), Traser (with “Trigalight”), Marathon and many other brands also use tritium tubes on certain models instead of Super-LumiNova. Tritium tubes remain popular with the military as well for the same reason as radium a century ago – a consistent glow without the need for a charge by external light.

Tritium Colours

Tritium has an assortment of coloured glows available, particularly with GTLS tubes. The brightest and consequently most popular is green, but there’s white, blue, orange, purple and yellow, with the latter three being the dimmest and used more for aesthetics. Most of the daytime colours (the paint without the glow) are either off-white/cream or pale yellow. Going back to Ball Watch Company, the Fireman Night Train III has an astounding 61 tritium tubes on the dial – one per hand (three total) and 58 around the dial in multiple glowing colours. In fact, buyers can even choose the lume colours, such as yellow hands with orange indices and blue markers, or the same setup with green indices and so on. Ball’s Engineer III Marvelight Chronometer Meteorite 40mm has 15 tubes with six different colours on the dial – yellow for the three hands and green, white, yellow, blue, orange and purple indices (a pattern repeated twice with green at 12 and 6 o’clock).

Luminova

By the late 1990s, conventional tritium paint was viewed poorly for its radioactive properties and even banned in some regions, despite it generally being safe for consumers (GTLS was a different story, but has always been a rarity overall that few brands embraced). A new mainstream solution was needed that provided a bright and lasting glow without a radioactive reaction. Contrary to popular belief, the next widespread watch lume, LumiNova, was invented in Japan, not Switzerland, and its origins go back to 1941 when Kenzo Nemoto developed a non-radioactive paint for the military’s aircraft instrument panels during World War II. It wasn’t LumiNova yet, but Nemoto & Co. was later established, and clock and watch hands were illuminated with the non-radioactive paint after the war.

It wasn’t until 1993 that LumiNova was created with an improved formula, and the company soon received a patent. LumiNova was based on strontium aluminate that glowed after absorbing external light (unlike tritium that glowed indefinitely on its own), and watchmakers began using it in small numbers by late 1994. It didn’t become an industry standard until 1998, the same year Rolex switched from tritium to LumiNova (with the well-known Swiss-only models), and it’s a short-lived but very important bridge between tritium and today’s Super-LumiNova.

Super-LumiNova

Super-LumiNova is an enhanced variant of LumiNova created by Swiss company RC Tritec AG, which was licensed to use LumiNova in 1993. It resulted from a joint venture between RC Tritec AG and Nemoto & Co., and the Swiss company LumiNova AG was soon formed with RC Tritec taking the lead. In 2000, Rolex transitioned from LumiNova to Super-LumiNova, with many brands following, and it quickly became the gold standard that remains today. This new “Super-LumiNova” was superior to LumiNova in a few ways – it was brighter, lasted longer after an external light charge and was more durable, resisting cracking and fading over time. Both LumiNova and Super-LumiNova hold a significantly bright glow for a brief period after an external charge, but the consistent and stable glow afterwards from Super-LumiNova is far superior, especially today.

There are generally eight Super-LumiNova glow colours (compared to six with tritium tubes), which are green, blue, white, yellow, violet, orange, pink, and ultramarine. Additional custom colours are also available. Brightness levels depend on colour and type, with C3 (green glow) and BGW9 (minty blue glow) being the brightest, respectively. There are multiple daylight colours as well (the paint colour before the glow), including white, yellow, green and blue, and then there’s “Old Radium” with a vintage orange/yellow hue to safely mimic the look of classic radium on vintage-inspired dials. These daylight colours can also be customized with black being a fairly rare and stealthy option. BGW9 is often the most popular as it’s almost as bright as C3, but with a neutral white daylight colour compared to C3’s more yellow/green hue. C1 has a pure white daylight colour, but isn’t as bright as C3 or BGW9 at night (even with its green glow).

To add to the confusion, several grades correlate with performance (similar to movement grades like Elaborated, Top and Chronometer). Standard Super-LumiNova is the “workhorse” grade that’s the least expensive with the shortest nighttime glow, while Grade A is an improved variant with a longer glow, like comparing Standard and Elaborated grade movements. Grade X1 is a big step up from the prior two, with a much longer nighttime glow as performance is improved by around 60% after two hours. The newest is Grade X2 and is around 40% brighter than X1 with a longer glow. It’s a significant leap forward and a world away from Standard and Grade A variants. Grade X2 was introduced in 2024 on the Panerai Submersible GMT Luna Rossa Titanio (PAM01507) and is now seen on others from the Submersible GMT and Luminor Marina lines. Accessible brands use it as well, like British watchmaker Farer with several collections, including the latest Aqua Compressor.

Lumicast

As with tritium tubes, there are Super-LumiNova options other than paint. Lumicast refers to a solid ceramic form of Super-LumiNova that can be used for applied indices and numerals, providing a bright and three-dimensional effect. The luminescent powder is mixed with a binder and then hardened in moulds, providing blocks of Super-LumiNova for a variety of creative designs. Any colour can be used for Lumicast, from C3 to BGW9 to Old Radium. Steel or gold (or other metal) indices can also be filled with Super-LumiNova for a deeper and brighter application. The lume is mixed with a varnish to keep it solid within the hollow index or numeral, and it results in a crisper look in daylight over traditional paint.

Chromalight

Although Super-LumiNova is the industry standard, some brands have introduced their own proprietary lume. Rolex started moving away from Super-LumiNova in 2008 in favour of Chromalight with a bright blue glow instead of traditional green, and it debuted on the Sea-Dweller Deepsea. It has a brighter glow and lasts longer than the Super-LumiNova it replaced, although this was many years before Grade X2 debuted with comparable and perhaps better overall specifications. Rolex claims Chromalight will last 8 hours in the dark, while X2 can effectively top 10 hours. In daylight, Chromalight has a nice white colour, similar to Super-LumiNova C1, and Rolex says blue is easier on the eyes with better overall nighttime visibility than green (your mileage may vary). Both Chromalight and Super-LumiNova are based on strontium aluminate, but the former has been tweaked specifically for Rolex.

LumiBrite

Seiko has its own proprietary lume called LumiBrite, which also evolved from LumiNova in the mid-1990s. Seiko added europium and dysprosium to the strontium aluminate mix for better brightness and a longer nighttime glow, and it absorbs light faster as well for a better initial burst. Many claim that LumiBrite is brighter than Super-LumiNova and Chromalight after the initial charge, but Super-LumiNova X2 lasts longer than both. Seiko dive watches arguably benefit the most with oversized LumiBrite indices and bright green glows during low light and nighttime dives. And to compete with the latest Super-LumiNova variants, Seiko introduced LumiBrite Pro in 2024 with even brighter glows and better performance. It debuted on some Prospex Black Series models like the SRPK43 and SSC923 and has since expanded. LumiBrite and LumiBrite Pro usually have a bright green glow, but some variants are blue.

Natulite

Not to be outdone by Seiko, Citizen also has a proprietary lume called Natulite. It’s comparable to many Super-LumiNova and LumiBrite variants, although there’s a bit of a grey area as to the exact tweaks that were made to the LumiNova base. Most Natulite watches have a green glow, but there’s also blue, and the Promaster Diver line is known for having excellent underwater legibility with Citizen’s lume.

Panerai

You’re familiar with the collections Radiomir and Luminor, but those names actually come from Panerai’s lume, starting in the early 20th century. The watchmaker uses Super-LumiNova today, but introduced “Radiomir” lume back in 1916 for use by the Royal Italian Navy, comprised of radium and zinc sulfide (the common formula at the time). Radiomir was initially named for a low-light gun sight (and torpedo tube aiming calculator) that Panerai patented using a radium and zinc sulfide powder within a sealed glass tube – “Radio” for radium and “Mir(e)” for sights. The watch lume that followed provided excellent underwater legibility, and in 1935, Panerai released the first Radiomir watch models as prototypes (named after the lume) for the Italian Navy with Rolex movements. A year later, the Radiomir ref. 3646 was released as a standard military issue, and the iconic design was established with the large cushion case and unguarded crown.

In 1949, Panerai trademarked the “Luminor” name as a tritium-based lume that was a safer alternative to radium. However, the watchmaker didn’t actually have access to tritium, and the US government could only produce small amounts in the 1950s for military use. The trademark came around 20 years before the Luminor tritium-based lume became a reality. The Luminor watches with the iconic lever-operated crown guards didn’t debut until 1993 for mainstream consumers, but Luminor models have been available for the Italian Navy since the 1960s. Sylvester Stallone was an early enthusiast and instrumental in the brand’s civilian popularity of the oversized watches, soon followed by Arnold Schwarzenegger. Both wore Luminor models in movies in the 1990s, which helped push global demand (Daylight for Stallone and Eraser for Schwarzenegger).

One of the Greatest Innovations in Watchmaking

Watch dial (and bezel) luminescence remains one of the most important innovations in watchmaking, allowing professionals and civilians alike to see the time and other vital information in darkness. Whether you’re diving in dark water or checking the time in a movie theatre, lume keeps the lights on (so to speak) without the need for batteries. It has a somewhat dark past (no pun intended) as radium was not only dangerous for consumers, but took many factory workers’ lives in the early 20th century (highlighted by the Radium Girls lawsuit). It was a very successful watch dial lume, nonetheless, remaining an industry standard for many decades until the mid-1960s. Tritium tubes and Super-LumiNova are the current champions of dial luminescence, but proprietary lume like Rolex’s Chromalight and Seiko’s LumiBrite are also some of the best (although the latter two are still based on LumiNova). In a world increasingly dominated by technology, old-school wonders like mechanical watches and battery-free lume remain timeless and still capture the hearts of consumers

3 responses

Long live lume!

Great article

Has anybody else noticed that, in the Rolex advertisement, radium is spelled wrong? “Raduim”.