All About the Different Crystals Used in Watches Today

There's more than just sapphire, and some alternatives do make sense.

If you’re not a big watch nerd like us, you likely don’t give a lot of thought to the glass covering watch dials. It’s not just a generic window and a bigger deal than you might think, as we’ll see in this instalment of the ABCs of Time. Some enthusiasts even demand one type over another, depending on the watch itself. Let’s travel back in time to the early 16th century, when the first primitive pocket watches appeared. A German locksmith named Peter Henlein (likely) developed the first “miniaturised” movement driven by a spring that was reasonably portable, but these early “pocket watches” were more akin to small clocks. Often referred to as Nuremberg eggs (Henlein was based in Nuremberg), these portable timekeepers were worn around the neck, had a single hour hand and usually a hinged brass lid as crystals weren’t a thing yet.

Nuremberg clock-watches spread throughout Europe during the 16th century, but the 17th century brought the more familiar pocket watch design that has endured for over 300 years. King Charles II of England introduced a new fashion in the mid-17th century, the waistcoat, which had a dedicated pocket for the burgeoning pocket watch and the concept of portable time went mainstream (at least for the well-to-do). At this point, “glass” crystals were commonly protecting the dials, although they were a natural quartz variant and not manufactured glass as we see today (hence “crystal” in the name). Chains or “fobs” kept the watches attached to waistcoats. Glass was the standard window for centuries, but modern materials in the 20th century really changed the game, coinciding with the proliferation of wristwatches.

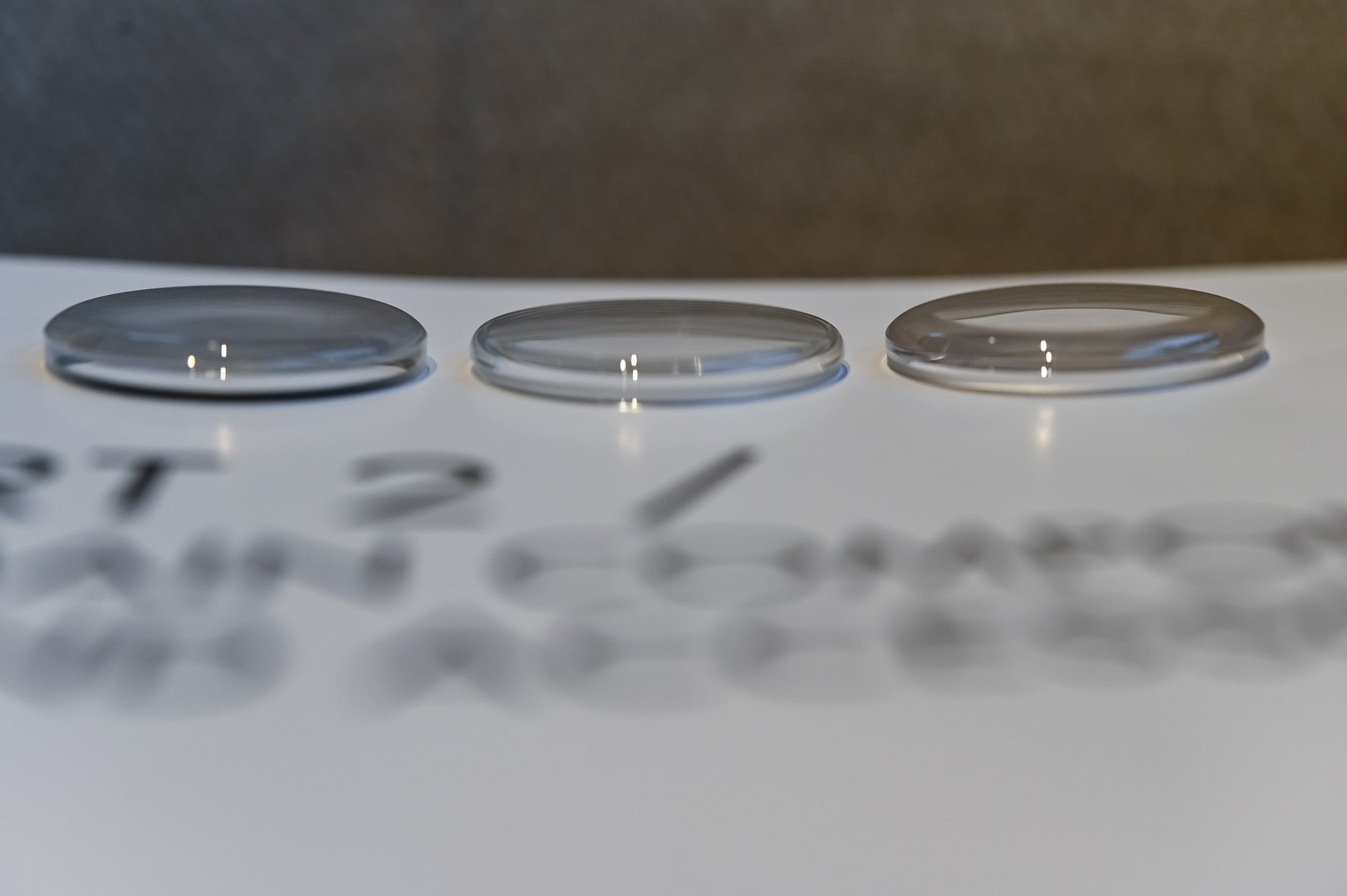

Mineral glass crystals

This is basically the mid-range material for watch crystals today, as it’s an inexpensive yet relatively hard option that’s superior to the old natural glass of the past. Many of these silica-based glass crystals are tempered – heat-treated to further improve scratch resistance and overall hardness. Common tools and methods are used for production, and they’re easily replaced; and you’ll often see them referred to as K1 glass. Some brands even have specific names – Seiko calls its mineral glass crystals Hardlex. Mineral glass is naturally less reflective than sapphire, so anti-reflective coatings are less commonly used, further reducing costs. It all sounds like the ideal material for crystals – inexpensive, scratch-resistant and optically sound – but there are disadvantages.

Although tempered K1 glass is scratch-resistant, it’s definitely not “scratch proof” and knocks and daily wear can lead to surface scratches and even pits. These (generally) can’t be polished out, and the crystal must be replaced, which can be an inconvenience and a moderate expense. The material is around 5 on the Mohs hardness scale, which is used to measure the scratch resistance of minerals. Diamonds are the most scratch-resistant at 10 on the scale, while the soft mineral talc is rated at 1. So, K1 glass is right in the middle, but still not suitable for high-end watches today, although some luxury brands use it for the exhibition case backs, as the wrist offers continuous protection. It should be noted that Seiko’s Hardlex is chemically treated to reach up to 7 on the Mohs scale (harder than stainless steel), so not all variants are the same. Mineral glass can also shatter, potentially damaging the dial and hands, while also leaving the case exposed to the elements. Obviously, water and dust resistance are out the window (pun intended) without an intact crystal.

With care and sometimes a bit of luck, mineral glass crystals can last for decades without fuss and are solid options for affordable watches. It’s usually the preferred material if sapphire isn’t used, but the next material on the list sometimes finds its way onto high-end pieces and was the preferred crystal for decades by heavyweights like Rolex and Omega.

Acrylic crystals

Acrylic is synonymous with plexiglass (a durable thermoplastic) and is specifically polymethyl methacrylate, which isn’t very scratch-resistant compared to K1 glass, but offers a warm aesthetic and, importantly, doesn’t shatter. Like Seiko’s Hardlex glass, some brands have their own special names for acrylic crystals – Omega traditionally calls it Hesalite. Acrylic is common for inexpensive watches today as it’s cheap and easy to manufacture, but high-end brands like Omega continue to use it for watches like the traditional Speedmaster Moonwatch Professional. Sapphire is also an option for the model, but acrylic again offers a warmer, vintage aesthetic, and there’s a history behind its use.

It’s called the “Moonwatch” as the Speedmaster was the first watch worn on the moon by Buzz Aldrin during the 1969 Apollo 11 mission. Acrylic was the only material considered for the crystal, as NASA couldn’t allow the potential of a shattered glass crystal contaminating the space capsule. Some pilot’s watches by Sinn also have acrylic crystals for this anti-shatter durability, and brands like Junghans have embraced them as well. Beyond the anti-shatter advantage, acrylic can also be polished, removing surface scratches to restore a perfectly clear finish. This can only be done a finite number of times as small amounts of material are removed during polishing, but it offers a quick and inexpensive fix without having to replace the crystal. When replacement time does arrive, it’s usually the easiest and least expensive of the main crystal types.

Acrylic crystals were invented in the 1920s and became a mainstream product in the 1930s, and were standard on military watches during World War II due to their high shatter resistance. Brands like Rolex used acrylic crystals for much of their existence and didn’t discontinue them entirely until 1991. It’s the least optically clear of the three main crystal types (acrylic, mineral glass and sapphire), but that provides its warm, vintage tone. Acrylic remains a popular option for affordable models from Swatch, Timex and many other “department store darlings” and certainly still plays an important role in modern watchmaking.

Sapphire crystals

Although once regarded as an expensive, almost niche luxury for high-end watches, sapphire crystals have become the norm and are now seen on mid-range and even many microbrand offerings. They were generally introduced in the 1960s, but use cases go back much further. In 1902, French chemist Auguste Verneuil perfected the process of making synthetic rubies, which soon replaced more expensive natural jewels in watch movements. Synthetic sapphire crystals, which are pure for the best optical clarity, have been seen in watchmaking as far back as the 1930s with a Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso.

Most natural sapphire is blue due to contaminants like iron and titanium, and other colours are somewhat common as well (this isn’t suitable for watch crystals). In the 1950s, Omega began using sapphire crystals sporadically, while Rolex started in the 1970s with the Datejust Oysterquartz (ref. 5100). The Rolex Day-Date, Sea-Dweller and Submariner were upgraded to sapphire crystals later in the 1970s, which prompted other luxury watchmakers to adopt sapphire over acrylic or glass.

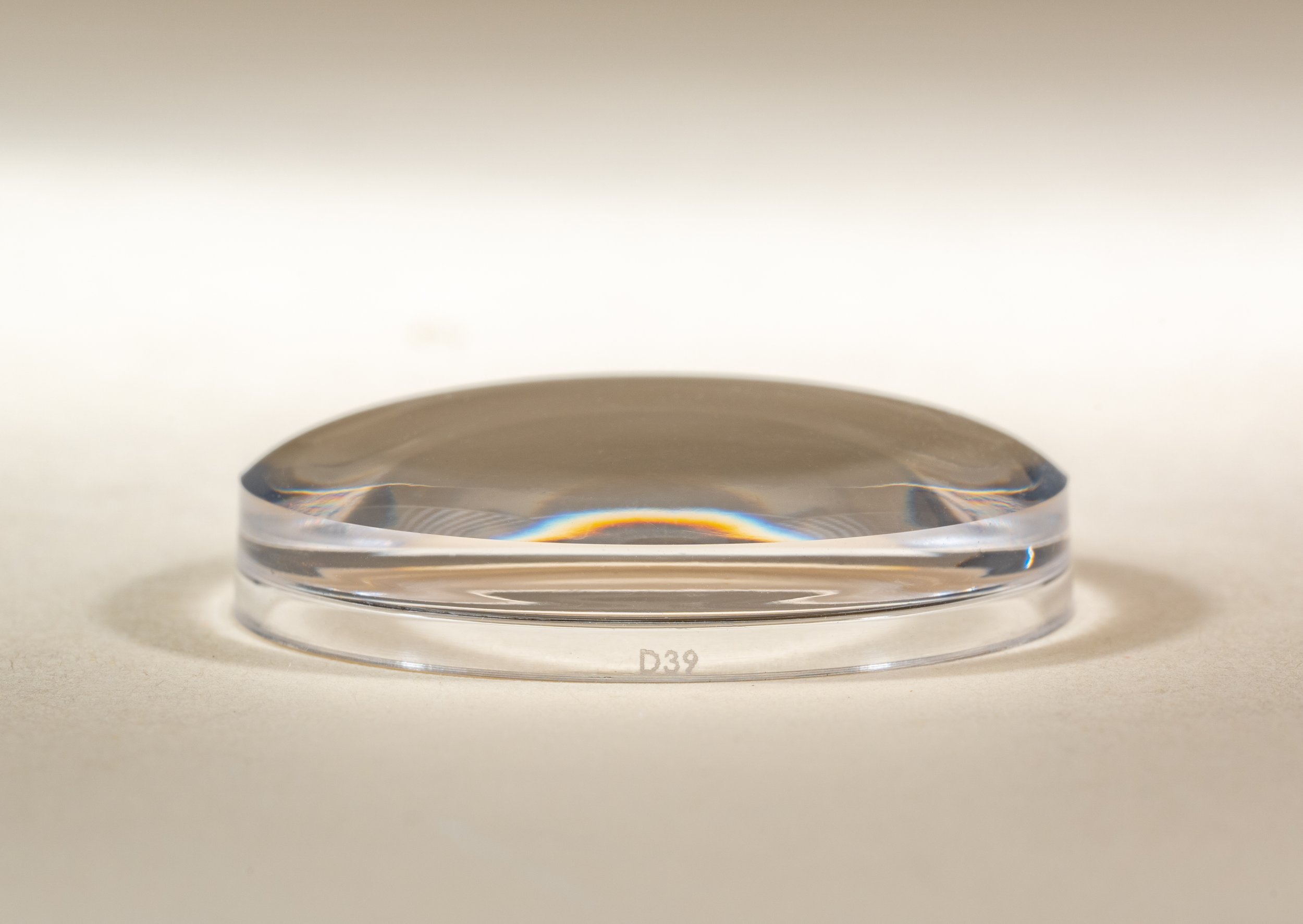

In a nutshell, synthetic sapphire is the crystallisation of pure aluminium oxide under extreme heat. It’s among the hardest and most scratch-resistant of materials and measures 9 on the Mohs scale (diamond blades are required to cut the material). Natural sapphire has the same hardness, but again (usually) not the colourless clarity. It’s least likely to scratch during regular wear, but it’s still not 100% scratch-proof and can’t be polished like acrylic. A damaged sapphire crystal from rough handling must be replaced, and it can also crack or shatter like mineral glass. Unlike mineral glass, however, sapphire crystals are very reflective and usually require anti-reflective coatings to counter this disadvantage. Applied via a physical vapour deposition (PVD) process, AR coatings can be used on both the inner and outer crystal surface, but outer coatings are prone to scratches and imperfections as they’re not as hard or scratch-resistant as the sapphire itself.

Watchmakers have really innovated with shaping the material, and sapphire has gone beyond just crystals, as we have full sapphire cases. The Jacob & Co. Astronomia is a great example of a sapphire case that almost disappears as the calibre with a triple-axis tourbillon and miniature solar system is visible in its entirety. Hublot went a step further and produced both a sapphire case and bracelet with the Big Bang Integral Sapphire. There are sapphire dials as well to hold dial elements while also showcasing skeletonised movements and so on. Sapphire crystals themselves can be flat for thin cases or domed and box-shaped to mimic vintage acrylic, providing dial distortions at angles. The material’s strength also allows dive watches to descend to extreme depths, something mineral glass and acrylic can’t claim. For example, the Rolex Deepsea Challenge has a hefty 9.5mm sapphire crystal and can descend to a depth of 11,000 metres, which is about as deep as the ocean gets.

Wild Card – Corning Gorilla Glass

We can thank Steve Jobs for this one, as he requested a tough, scratch-resistant, chemically strengthened glass for the iPhone, but its history goes back several more decades. Chemcor or “muscled glass” was developed in the 1960s by Corning and famously used in Plymouth and Dodge race cars in the late 1960s for both strength and low weight. In 2006/2007, Jobs was angry about iPhone prototypes having plastic screens that easily scratched, so Corning delivered its first “ultra-thin” glass screen covers for the 2007 iPhone debut. Gorilla Glass went on to become the standard “crystal” for smartphones and many other electronics, and the latest generations include Gorilla Glass Armor, Ceramic and Victus variants. Scratch and crack resistance improved with each generation and helped revolutionise the toughness and daily practicality of both smartphones and smart watches.

So, Gorilla Glass naturally comes to mind as a viable alternative to mineral glass for wristwatch crystals. It’s not as scratch-resistant as sapphire, but it potentially holds up better than typical mineral glass and certainly acrylic. For wristwatches, it’s still most common with smart watches, although many of those have moved to sapphire crystals like Apple Watches and Samsung Galaxy Watches. Vortic Watches, a US company based in Colorado, repurposes vintage pocket watch movements for 3D printed wristwatch cases, which use Gorilla Glass crystals over mineral glass. It’s currently rare for traditional watchmakers to use Gorilla Glass crystals, but Vortic has proven that it’s an excellent and cost-effective alternative to sapphire.

Final Thoughts

It’s easy to simply declare sapphire as the superior watch crystal and move on, but each type has advantages and disadvantages. Sapphire is the most expensive, can’t feasibly be restored if damaged and is highly reflective, requiring anti-reflective coatings for most high-end watches. And despite its incredible hardness, sapphire is somewhat brittle and will crack or shatter from a significant impact. Mineral glass is a perfect middle ground between cost and durability, but it’s also prone to cracks or shattering and can pick up scratches over time. Theoretically, mineral glass can be polished to remove some surface scratches, but in reality, most damaged crystals need to be replaced. An advantage mineral glass has over sapphire is its more anti-reflective quality, so anti-reflective coatings are often unnecessary.

Acrylic is generally considered the cheap stuff today, but not only was it the gold standard for decades, but it also remains a shatter-proof, warm and vintage-inspired alternative to the above options. It can also be polished to remove surface scratches, so a quick and cheap fix will restore acrylic crystals to a new condition (even at home). And if people didn’t like the qualities of acrylic, Omega wouldn’t continue selling a traditional Speedmaster with a Hesalite crystal. As far as Corning Gorilla Glass, it’s the go-to material for smart watches, fitness wearables, portable gaming and more, and I’d be surprised if it didn’t trickle down to more traditional watch brands in the future.

2 responses

Thank you for this breakdown of the different materials used for wristwatch “crystals”, including for what actual material is used in the Omega “hesalite” crystal, and in Seiko’s “hardlex”.

Excelente matéria!