Everything About The Springs Inside a Mechanical Watch

We all know there’s a "power" spring within a mechanical movement, but a watch still can’t function without several other vital springs.

In a basic mechanical movement, there are two primary springs: one that delivers power and another one to keep it accurately beating. But others are essential for this overall dance to work. Once complications are added, even more are needed and complex pieces can have dozens of springs. When most people think of a spring, a long and cylindrical metal coil comes to mind, like one in a retractable ballpoint pen, but springs inside of a mechanical watch have many different shapes (although the same general concept applies). Let’s look at the two primary and not-to-be-ignored secondary springs that work together as a team in a basic mechanical movement.

The Mainspring – power supply

A mechanical movement starts with the mainspring, which is the power source of a watch. It’s a long, thin coiled ribbon of steel or metal alloy that lies flat inside a barrel, slowly unwinding as it sends power through the gear train to the balance wheel and escapement and, of course, the dial’s hands and various complications (if applicable). Modern mainsprings are often made from Nivaflex, comprised of an anti-magnetic cobalt-nickel alloy with a high tensile strength – 45% cobalt, 21% nickel and 18% chromium (with small amounts of iron, tungsten and other metals). The mainspring can be wound manually or via an automatic weighted rotor, including an integrated micro-rotor or peripheral rotor. Before the first quartz watch in 1969, battery-powered watches replaced the mainspring with an electronic equivalent, like Hamilton’s Ventura in 1957, aiming to eliminate the need for winding in an otherwise mechanical movement. These early attempts were temperamental and never able to replace physical mainsprings en masse.

At the start of the 15th century (almost a century before Columbus sailed), mainsprings began replacing traditional hanging weights in clocks, allowing for much smaller and even portable (or luggable) clocks that didn’t require substantial vertical space underneath. The Burgundian clock from around 1430 is the oldest known spring-driven portable clock, originating in the Belgium/Northern France area (as we know it today) and still functional at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum. German locksmith Peter Henlein is credited with inventing the first pocket watch powered by a mainspring – in reality, these early timekeepers were basically miniature clocks worn around the neck, but also the catalyst for proper pocket watches moving forward. There are generally two configurations of mainsprings today – one that’s attached to the barrel wall for hand-wound movements, so the crown stops when fully wound, and one with a bridle for automatics (known as a slipping spring), where the end can slide along the barrel wall when fully wound to prevent overwinding and damage from the winding rotor. Think of it like a friction clutch in a car.

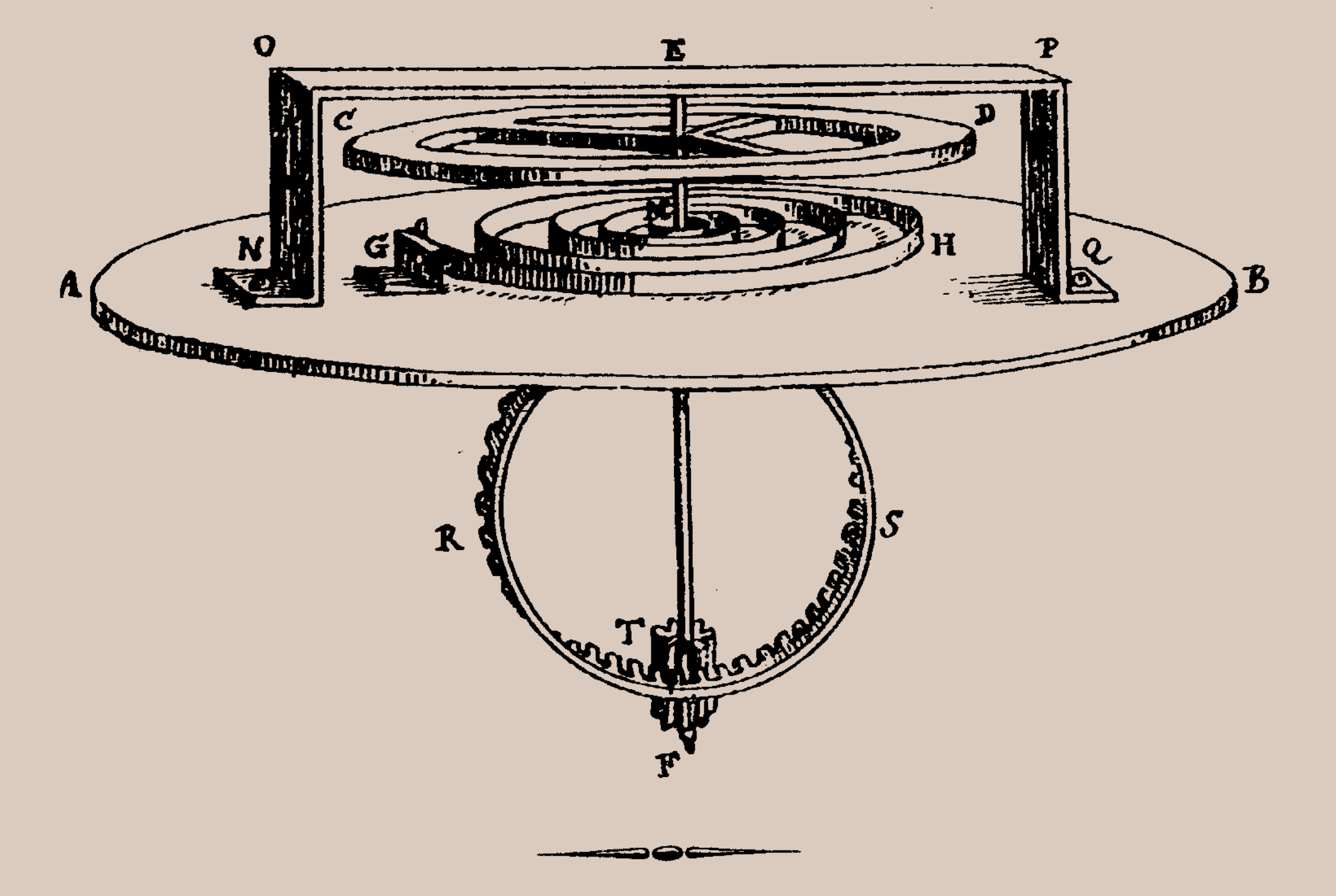

The Fusee and Chain

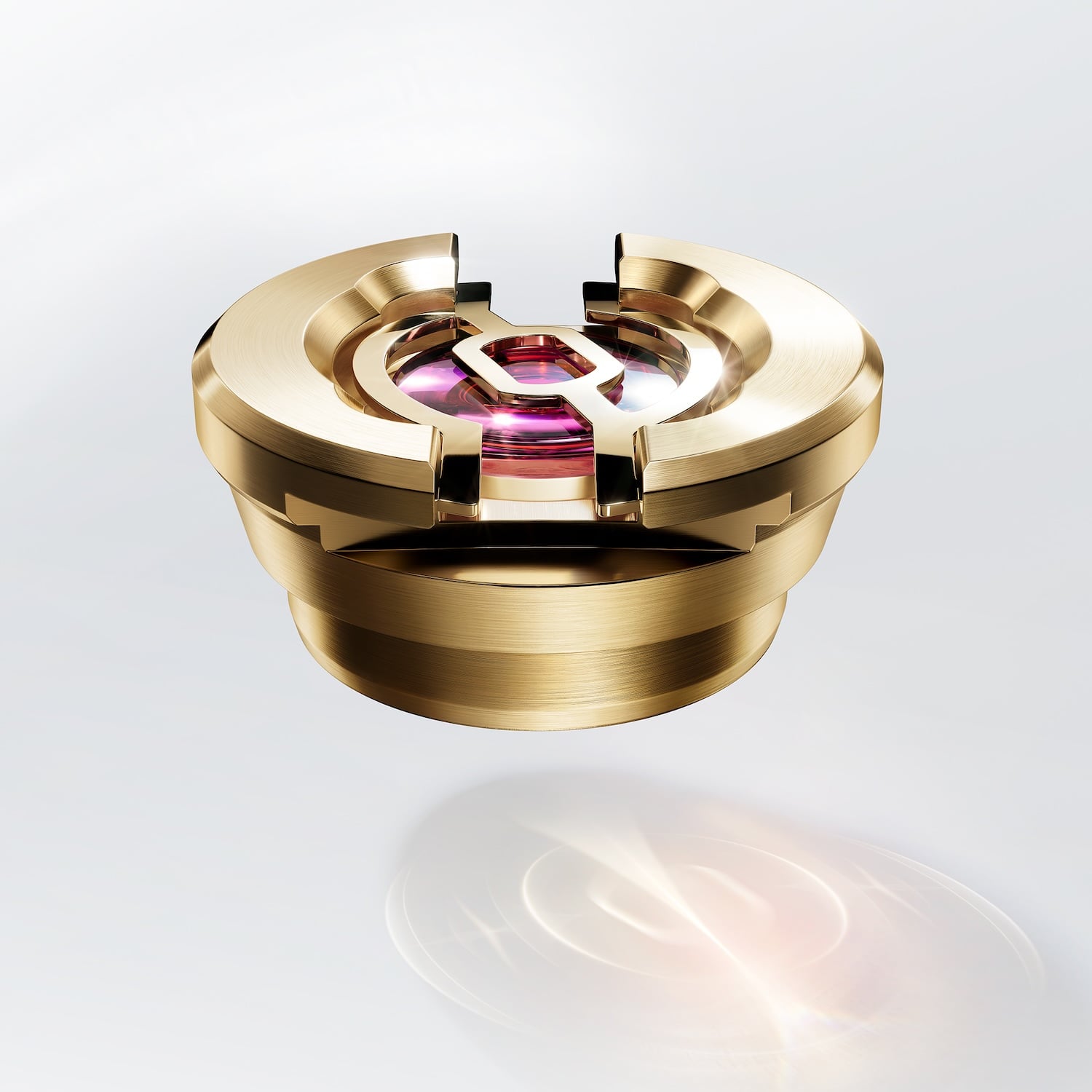

Early metal mainsprings weren’t made from fancy Nivaflex and suffered from significant variances in torque, losing power as they unwound. To counter this, a fusee and chain were often used – basically a metal cone with a chain wrapped around it. Starting at the tip when fully wound, the chain moved down to the wide base as it unspooled, compensating for the weaker force of the unwinding mainspring to maintain consistency throughout the gear train. It’s kind of like a Continuously Variable Transmission (CVT) in a watch. This was used in clocks as early as the 15th century, but didn’t make it to pocket watches until the mid-17th century. Modern mainsprings and better engineering have made the fusee and chain obsolete today, but a handful of high-end watchmakers toy with the design for tradition and the uniqueness of the setup – A. Lange & Söhne, Breguet, Ferdinand Berthoud, Zenith and more. It’s unknown who exactly invented the fusee and chain, but the concept and drawings trace back to Leonardo da Vinci.

Double Barrel (and more)

Some watches have dual barrels (or more… many more) for multiple reasons, but the three most common are to increase the power reserve, to provide a more stable delivery of the torque to the regulating organ, or to provide an independent power source to power-hungry complications like repeaters/grande sonneries or chronographs. There are generally three configurations: 1. The barrels work sequentially in a serial setup, so the second barrel only takes over after the first is unwound, doubling the power reserve, 2. The barrels work together in a parallel setup, providing a more constant force for accuracy (balance wheel has increased amplitude) and 3. The barrels work independently of each other, powering time with one barrel and power-hungry complications with the other. Some watches today can get a full five-day power reserve or more with one barrel, so double barrels in that capacity are less common.

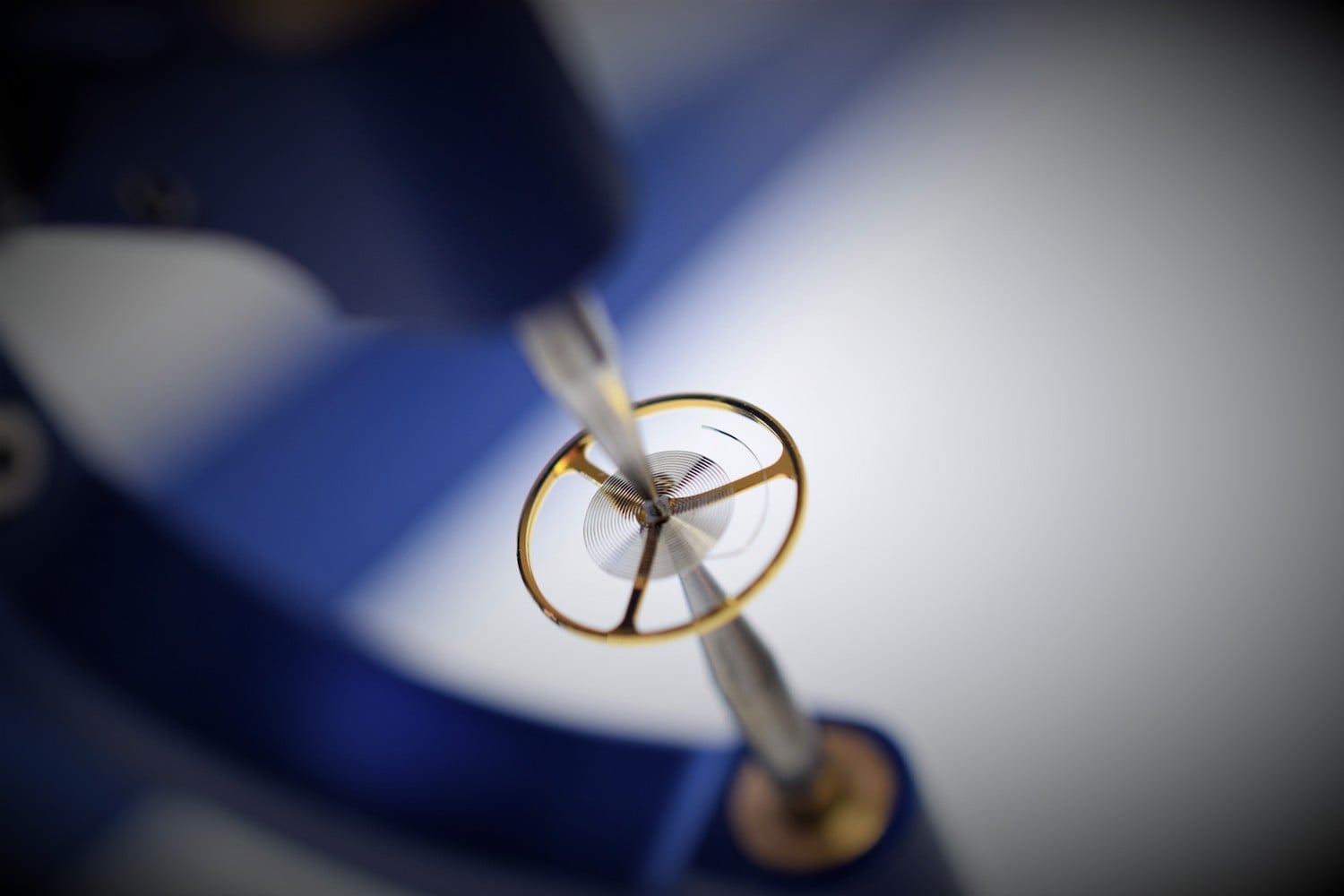

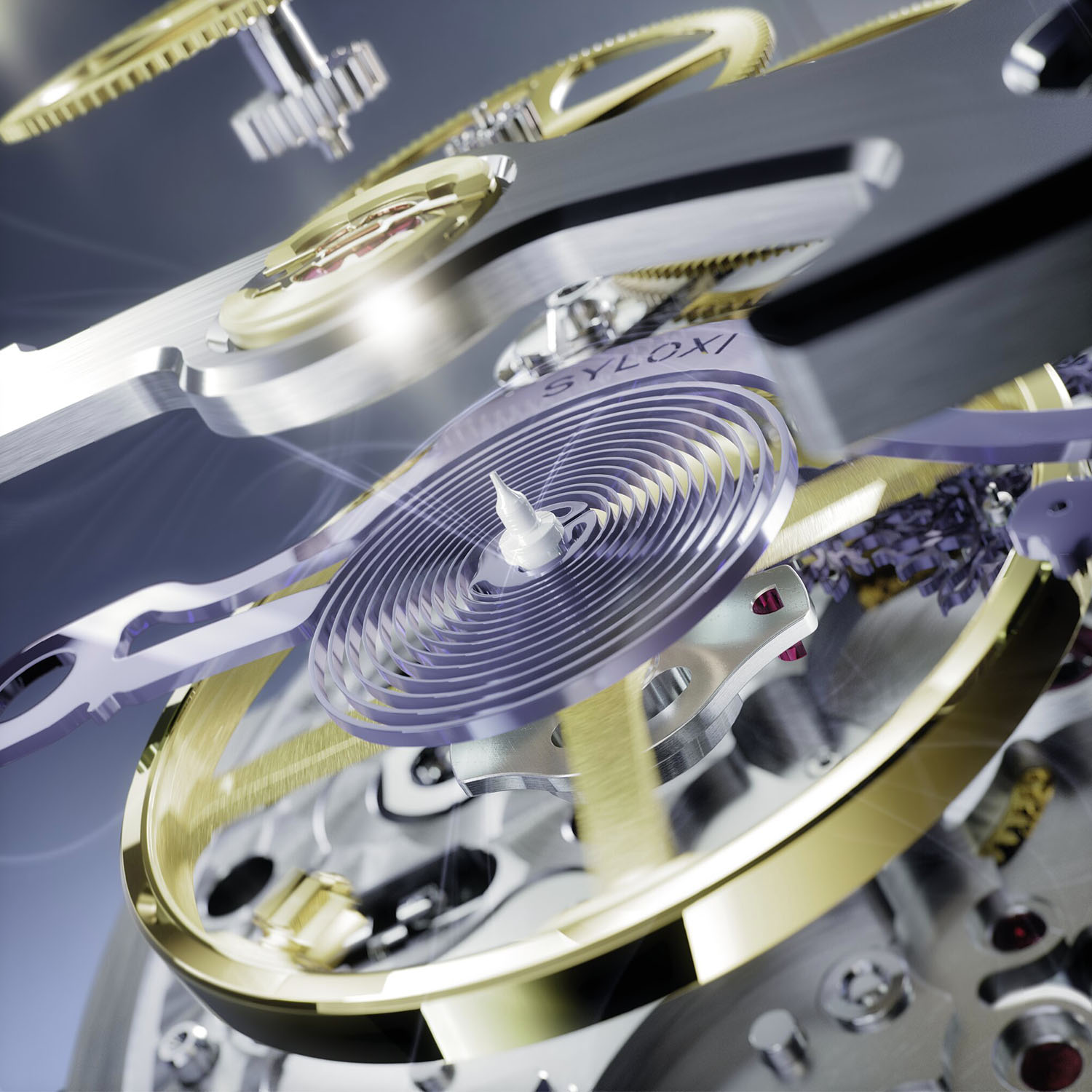

The Hairspring or Balance Spring

The hairspring or balance spring (names are synonymous) is a very fine, coiled spring within the balance wheel that controls its oscillations or the beat of the watch. Working together with the balance wheel and escapement (altogether making the regulating organ), the spring generates the heartbeat that regulates the speed of the gear train and, consequently, the accuracy of the watch.

The back-and-forth swing of the balance creates the specific oscillation frequency of the movement – 28,800vph (4Hz) or 21,600vph (3Hz) and so on. Hz (hertz) defines how many times a full back and forth swing of the balance happens per second. Vph (vibrations per hour) measures one swing at a time, so 28,800vph is actually 14,400 full oscillations, as the tick and tock are both counted.

Balance springs come in various materials, with silicon being a somewhat recent and popular choice as it’s anti-magnetic, very durable and lightweight. Ulysse Nardin was the first to use silicon components in 2001 (within the Freak), but a collaborative agreement among Rolex, Patek Philippe and the Swatch Group created silicon hairsprings with a protective patent. These hairsprings have become more widespread today within the Swatch Group and now outside watchmakers following the expiration of the patent in 2021. Nivarox nickel-steel alloy is another common choice, which is also magnetic-resistant and temperature-resistant. Some watchmakers have their own materials of choice – Rolex developed an alloy of niobium and zirconium called Parachrom, Seiko developed another proprietary alloy called Spron, Swatch Group’s Powermatic relies on Nivachron, and TAG Heuer recently unveiled TH-Carbonspring, made from carbon nanotubes (as an alternative to the patent-protected Silicon).

Very few watchmakers produce their own hairsprings (but so is the case for the mainspring), so the majority of in-house movements generally use outsourced hairsprings. Nivarox, which is a subsidiary of the Swatch Group, is the biggest Swiss manufacturer of hairsprings and provides the majority to Swiss brands. Precision Engineering AG is a sister brand of H. Moser & Cie and its supplier (both are subsidiaries of MELB Holding, although Precision Engineering AG also operates independently). Other high-end watchmakers with in-house hairspring production include Rolex, Patek Philippe, Bovet, Ulysse Nardin, Schwarz Etienne, Raketa, and A. Lange & Söhne.

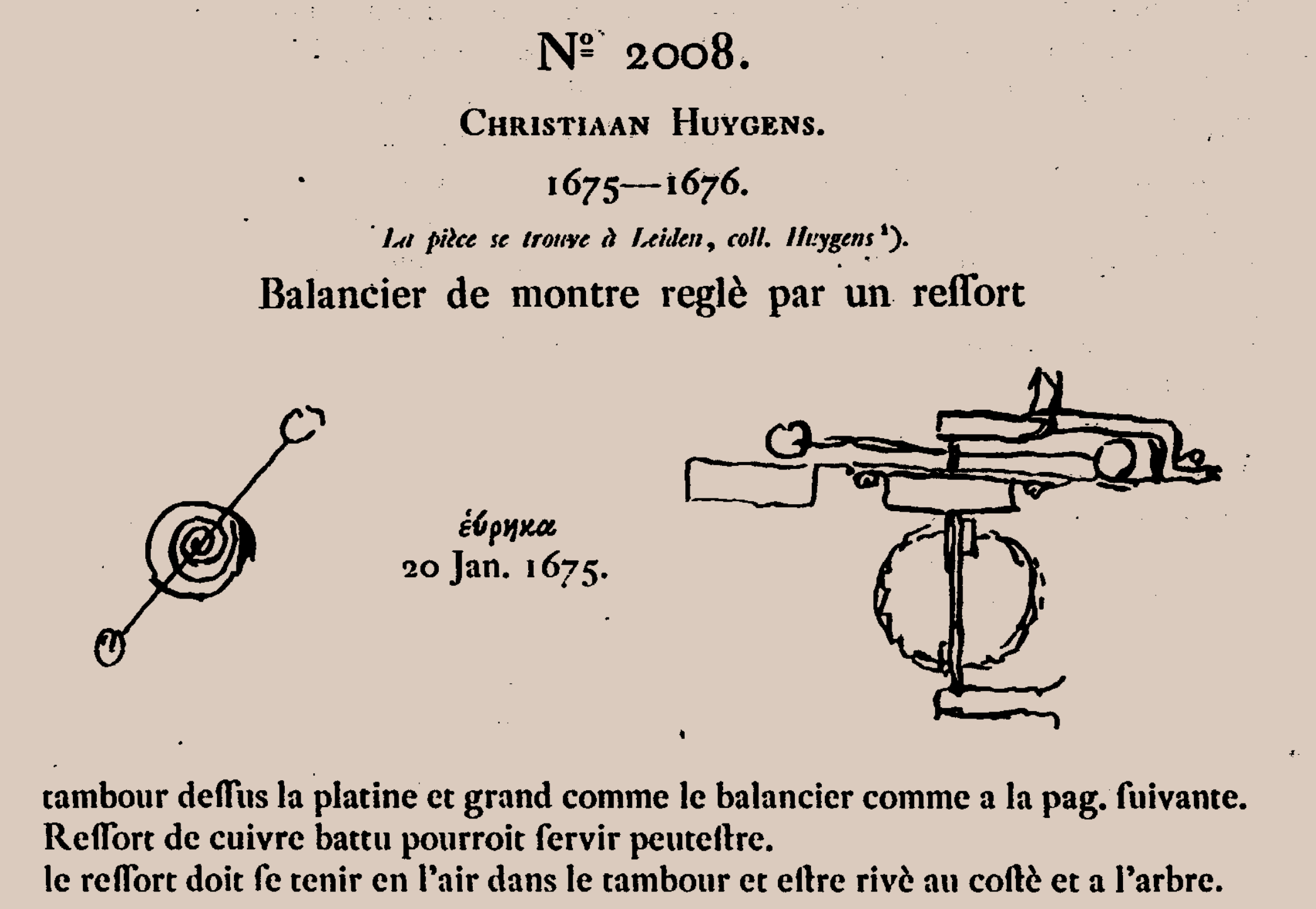

Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens invented the hairspring in 1675, although Robert Hooke could have developed the idea around 1670 (without a working sample). It replaced early foliot mechanisms and revolutionised the accuracy of watches, and remains a key standard of watchmaking today (along with the lever escapement and watch stem and crown). A significant advancement to this came in 1795 from Abraham-Louis Breguet, where the outer coil was raised above the otherwise flat coil and then curved towards the centre. This eliminated the lopsided expansion of a totally flat spring to improve isochronism and accuracy. The now symmetric spring movement from this Breguet overcoil also reduced positional errors (negative changes when the watch shifts orientation) and wear on the balance staff. It’s a standard for many high-end movements today, but flat hairsprings for mass-produced counterparts are much improved with modern materials and achieve comparable accuracy results.

Click Spring

To prevent the mainspring from unwinding, a pawl and click spring are used to keep the ratchet wheel secured and unable to spin freely – the ratchet wheel is a gear on top of the barrel, so the mainspring can be wound via the crown (this is separate from the teeth on the barrel itself that mesh with the gear train). The pawl is a small lever that engages with the ratchet wheel teeth to lock it in place, while the click spring simply pushes the pawl against the ratchet wheel. As you wind the watch, the clicking noise comes from the pawl snapping into each tooth as it’s pushed by the click spring to keep it from coming loose. Simple yet vital for the watch to wind and properly function.

Jumper and Setting Lever Springs

For watches with date windows (including day-date, etc.), a jumper spring is needed to push a lever into the date wheel until force is generated to push (or jump) it to the next digit (the spring releases tension during this instant jump). After the jump, the jumper spring and lever hold the wheel’s position until the next jump. This also applies to similar concepts like jumping hours. A setting lever spring is used for the crown and stem, holding the right position as you pull the crown to set the time, date, wind the watch and so on (you can feel and sometimes hear the click as the crown is pulled to each position).

Shock Absorber Springs

Most mechanical movements today have shock resistance, like Incabloc, Diashock or Parashock, and springs play a vital role. Shock protection generally focuses on the balance wheel and its staff via relevant jewels. These jewels are secured with specialised spring systems, allowing them to move and flex a bit during a hard knock or shock that prevents the staff from breaking and the jewels from potentially falling out – a suspension system. There’s a standard for a watch to be labelled as shock resistant – ISO 1413 – that requires testing for specific shocks on the crystal and case side. Vintage watches without shock resistance were much more susceptible to broken balance staffs and sheared off jewels.

Just the basics

This isn’t an exhaustive list of springs, but it covers the basics of a mechanical watch. Once complications are added, like chronographs and repeaters, a smorgasbord of specialised springs is introduced. A grand sonnerie, for example, has approximately 22 blade springs for the striking mechanism alone, while jump springs are needed for each gear in the striking train. These movements can have over 1,000 parts with a lot of tiny springs involved. A chronograph adds dozens of springs to the basic movement, as does a perpetual calendar. The king and queen are the main players on a chess board (let’s call them the mainspring and hairspring), but you can’t have a game without the rest of the pieces, which are the other vital springs within a mechanical movement. Perhaps not the best analogy, but you get the idea. Without springs, we’re back to archaic clocks with verge-and-foliot designs in the 14th century (and a basic game of Checkers).

6 responses

Though “it’s not an exhaustive list of springs” as you mentioned, I would hope that you could include remontoir d’égalité, a relatively obscure but highly significant device in high horology to obtain the constant force.

@Weitsu Fan Yes, rare but very important. This was just covering the basics for a standard mechanical movement.

The man who really understands all this is Dr smith .George Daniels protege.

@ErikSlaven Thanks for replying. The reason for my feedback is seeing you mentioned the fusee and chain mechanism and especially the picture of the modern Ferdinand Berthoud’s illusive and superb FB watch which is beyond the basics. Excellent article and hope there will be a sequel.

Robert Hooke first proposed a sprung balance around 1658 and it is documented that he had a working pocket watch (made with the assistance of Thomas Thompion) which he presented it to the Royal Society on 23 June 1670.

This takes nothing away from Huygens, his elegant spiral was a huge step forward for accuracy, and both men deserve fair recognition.

Robert Hooke was paranoid about people stealing his ideas and took the notes of the meeting that spelled out his hair spring. The notes were later discovered but over three hundred years late.