Your Guide to the “Dirty Dozen” – Including the Only British Member, VERTEX

Simple timekeepers that have played a critical role in the successful execution of British military operations.

In our modern age of smartphones and wearable tech, it’s easy to forget just how indispensable the humble mechanical wristwatch once was. Yet even a brief foray into the world of military watches is enough to provide a vivid reminder. Rugged, reliable and entirely fit-for-purpose, these simple timekeepers have played a critical role in the successful execution of military operations that dramatically shaped the course of modern history. Particularly during World War II, the period which we will be focusing on for the purpose of this article. Arguably the best-known such watches from this era are those of the British Military. More specifically, the Dirty Dozen.

Background

Chances are you’re already familiar with the Dirty Dozen, or have at least heard the name. That’s probably because the “Dozen” is amongst the most sought-after series by military watch collectors. If you’re not familiar with the name though, allow me to provide a brief introduction. The use of wrist-worn watches in military conflict really began in World War I. Pocket watches – the popular choice of men of the day – proved too cumbersome and time-consuming to use in the trenches. Not to mention the distraction of fumbling around with the dust cover, etc. could inadvertently expose your position to enemy snipers.

The initial – albeit rudimental – solution soldiers came up with was to strap their pocket watches to their wrists for easier access. This soon evolved into the “trench watch”, which basically used a small pocket watch case with wire lugs soldered on either end so a strap could be attached. The designs were not standardised, and the soldiers typically had to purchase these watches themselves. Meaning they were not issued by the government.

The design of these watches continued to evolve throughout the war based on the feedback from the constant “field testing” they were subjected to. For example, white dials with black numerals were soon inverted as it became clear that white text against a black background was more legible. Likewise, luminous paint – containing radioactive radium – was introduced to enable reading in low-light conditions.

By World War II, the wristwatch was well and truly established as an essential part of a gentleman’s daily attire. Assuming he could afford one, of course. Pocket watches still persisted – even within the military – but their popularity continued to wane. As you might expect, the wristwatch played an even more significant role in the Second World War than it did in the First. Yet there wasn’t a great deal of standardisation in the design of these watches until the early 1940s.

The Dirty Dozen

According to the history books, in 1943 Commander Alan Brooks (later to become Field Marshal) recognised the value of having a general-use timepiece for the armed forces. Until then almost all service watches were personal civilian items. Given that this “general-use” timepiece was destined for a very active war zone, the MoD set specific criteria for how it should look and function. These included:

- Black dial with Arabic numerals, subsidiary seconds at 6 o’clock and railroad-style minutes

- Luminous hour and minute hands plus luminous hour markers

- Movements with 15 jewels, 11.75 to 13 ligne in diameter

- Shatterproof Perspex crystal

- Waterproof to the standards of the era

- Precision movements that had to be regulated to chronometer criteria in a variety of conditions

- Rugged case capable of diminishing the impact of shocks

- Water-resistant crown of good size

The military code for these watches was W.W.W. (Watch, Wristlet, Waterproof). They were also required to be engraved in three places with the Broad Arrow or Pheon (which denotes property of the British Crown.) On their casebacks was the descriptive code W.W.W. Two serial numbers could be found as well, one being the civil serial number of the manufacturer and the second a military one which started with a capital letter.

As part of its brief, the British MoD clearly stipulated that these watches were explicitly meant for ‘General Service.’ This did not mean that each soldier would be eligible for one; it was and certainly remains over-the-top to provide a watch regulated to chronometer standards for every soldier. With the term ‘General Service,’ the British meant that these watches would be issued to special units and tasks respectively such as artillery members, staff members, engineers and personnel of the Communications Corps.

At the time, British watch factories already had their hands full with the manufacturing of munitions and weapons. So, requisition officers were sent to Switzerland to find companies that could fulfil the order. In the end, twelve companies would be selected: Buren, Cyma, Eterna, Grana, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Lemania, Longines, IWC, Omega, Record, Timor, and Vertex. (Although Vertex was technically a British watch company, it had Swiss Manufacturing plants.)

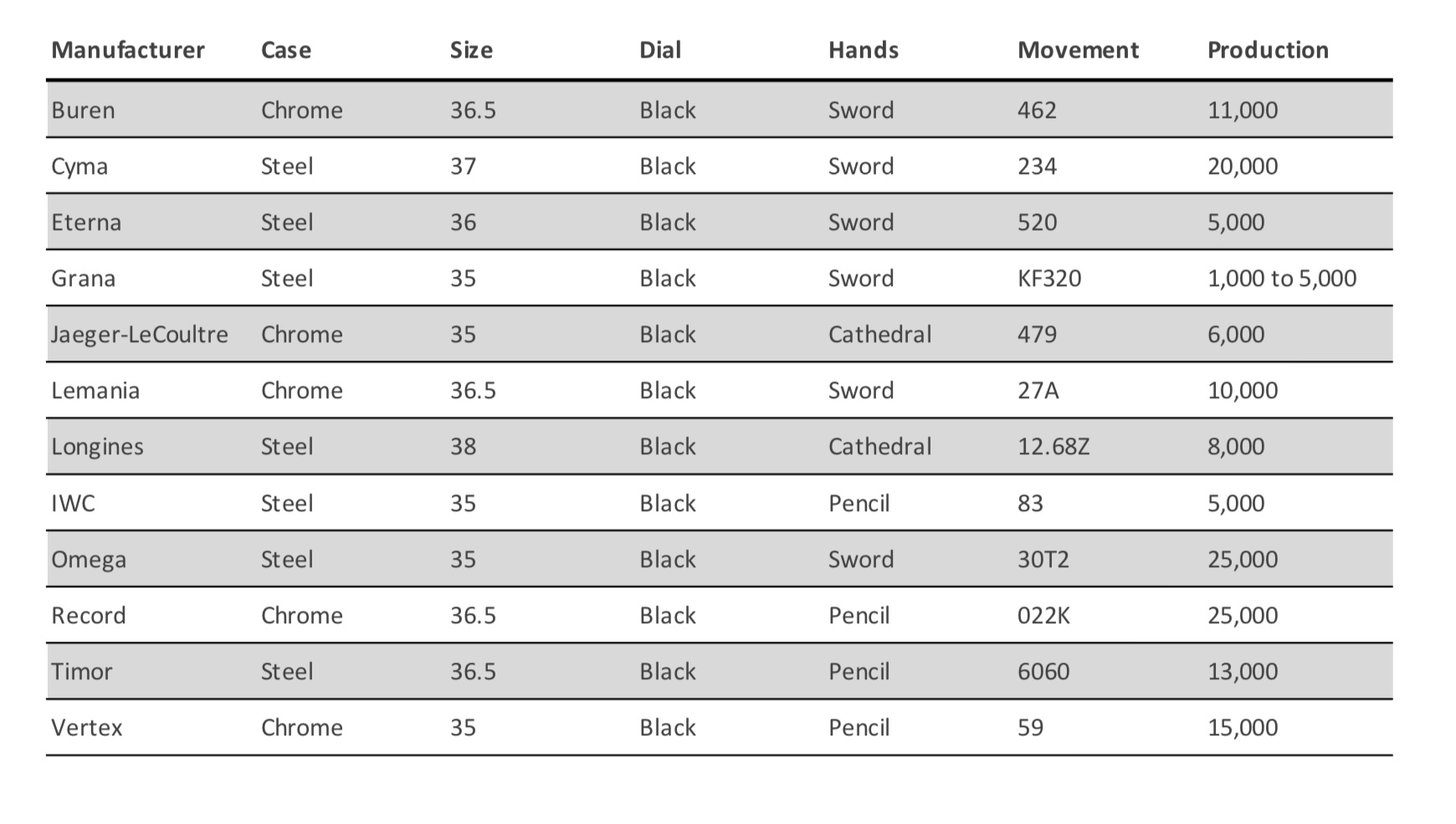

About 145,000 W.W.W’s were delivered to the British military by all 12 manufacturers. The table below from Konrad Knirim’s book British Military Timepieces provides an overview of how many watches were contributed by each maker:

As you can see, some – such as Grana and Eterna – produced relatively low volumes. This makes it particularly challenging for collectors trying to find nice examples of each to complete their “Dozen”. A task that is made infinitely more difficult by the fact that these watches were serviced, let’s say without the greatest of care, by the R.E.M.E (Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers) who often chopped and changed parts between the various models. On the other hand, spending a lifetime searching and collating a complete set must be a very rewarding experience indeed.

The Vertex Connection

As the only British member of the Dirty Dozen, Vertex stands out. It’s true that the company had manufacturing capabilities in Switzerland thanks to its partners there. But it’s also likely that Henry Lazarus, son-in-law of company founder Claude Lyons and a captain in the British Army, was able to exercise his influence to get his company on the list.

That’s not to say Vertex didn’t deserve to be there. Far from it. After all, the company had been supplying watches to the British military since 1915. And as you can see in the table above, Vertex provided more than its fair share of the total, with a contribution of 15,000 pieces of its Cal 59 Nav watch.

It is this same watch, along with the requirements set out by the MoD, that Don Cochrane used as the basis for the M100; the watch that relaunched the Vertex brand in 2016. If you don’t know who Cochrane is, you can read our interview with him here. The M100 – and the later M100B – are not intended as direct homages to the Cal 59, but rather draw on it for inspiration.

The result is a contemporary tool watch with obvious military undertones, satisfying both the requirements of the MoD and the modern watch lover. It won’t suit all tastes, and unfortunately for the many military watch collectors out there, it won’t allow you to complete your “Dirty Dozen” set either. But it is still a very nice watch all the same.

More details at vertex-watches.com.

Opening photo credits: A Collected Man

11 responses

Thank you for this article. It is always nice to be reminded that the purpose of a watch is not to signify one’s place on the socio-economic ladder, or “to provide a cohesive brand identity”, or garner likes and hits to keep your company profile relevant. I wonder just how much punishment these watches could take and how many survived WWII in working order.

Sorry…. where is the Panerai? In the Ladies Theatre Elegant Jewels section??? 🙂

Hi there,

thanks for the article. I have one question, maybe it is a bit stupid…. Switzerland was sourronded by the axis forces. How did the British officers reached Switzerland and how did the watches reached the Allied?

Thanks and sorry for my bad english

Christoph

Thanks for a very well written and informative article.

As a watchmaker I enjoy reading things like this.

Thanks, Tom – very interesting article

Tom,

How does this coincide with the American GI issue watch development at the same time? I know that’s a broad question but they seem too similar to be coincidence.

Thanks

collective and amazing article.these are very beautiful historic timepieces.

I just picked up a “Vintage Dirty Dozen Rolex Military Watch”. Any input? I can’t find another like it anywhere on the web. It says Rolex Shock-proof on the dial & has the same smaller seconds dial located at 6 o’clock which somewhat covers the 5 & 7 adjacently. It it says 17 Rubies on the movement. I see Omega made the cut as one of the Dirty Dozen but not Rolex. I also see & know Rolex holds their value better. Im not sure what I have here. Any ideas or comments? Thanks! I wish I could add a pic to this post.

RLTW

ew742

Because Switzerland was neutral, it could import and export through normal processes, although subject to some restriction by Germany. Material was often railed to Portugal, and from there to Britain.

Hi all,

Excellent article, I am an old-time watchmaker and I have 2 of these Dirty Dozen watches, Vertex (Revue 59)A6470 and Lemania (27A) 5469.

Any idea what they are worth?

Both these watches are in good condition for their ages.

Any advice would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks

David Malik(old watchmaker)

I have a cyma www that was issued to my father in 1958 when he was serving in the Grenadier Guards. He was involved in the anti EOKA terrorist police action there. He was the O.Cs driver/bodyguard hence why it was issued to him. His O.C got it written off as lost so he could keep it instead of returning it to stores. It’s all original as it was issued to him brand new other than a replaced balance staff .