Testing (really testing) the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon (and see if such mechanisms have a chronometric interest)

The watch we’ll test today is worthy of a Chronometrie contest. It has been created with one unique goal in mind: being as accurate as possible, in all positions and during the whole range of its power reserve. Usually, we would have written a review exposing the case, the dial, the finishing or the wearability of the piece. However, with the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon, this would have been too short. We had to test it, and when I mean “test”, I mean looking at it on a watchmaker’s bench, with professional measuring tools. So here we are, with the test (and not the review) of this demonstration piece, and answers about the utility of such complex devices in a watch.

Preamble

Why such a review today? Why with this watch? Usually, our reviews, which are not known to be short of explanations, are what we can call in-depth stories (and no ego here, just pure facts). However, today, we’re not going to look at this watch like we usually do. We’re not going to debate about aesthetics (even if the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon is superb), we’re not going to look at wearability or finishing’s, or at least, not in the same way. Today, we’ll look at accuracy and we’ll argue if stacking a double barrel, a tourbillon and a remontoire (a constant force device) in a single watch has a real interest.

Why don’t we do it in other reviews? In fact for many reasons. First of all, pieces we receive for reviews are 1. Press watches that go from one show to another, from a boutique to another, from a journalist to a blogger. Thus, they usually are quite mishandled and in poor conditions 2. They can be pieces especially send to us, and of course, especially regulated to be even more accurate than commercial versions. Objectivity in both cases is affected and results might be better / worse than a regular piece. In a column written on Hodinkee, Jack Forster explained why they never test accuracy. In many ways, I must agree with him. The conditions are not always perfect and we (journalists) are not knowledgeable enough to properly interpret these results. Then, there’s the issue of the need for such a test. Do we need to test a watch with ETA movement? Certainly not. Watches that don’t come with a specific chronometrer certification (Geneva seal, COSC, Metas, Rolex Superlative…) are regulated on average and, from a piece to another, large variations can be seen. And in the end, does an ETA-powered watch need to be super accurate…? Probably not.

However, when you have a piece like the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon in your hand, it would actually be a shame not to test what makes this watch so particular, so complex and so expensive. We talk about a watch that was made to be precise and all its features are there for this single reason. In fact, we’re not honoring it with a normal review. This why we’ll look at it in a different, chronometric-oriented way.

How we came to test such a watch

If you remember, last year, I wrote a review of this watch. I did this review after having the opportunity to touch and feel it for a few hours, but in the middle of Baselworld. It allowed me to understand the technicality, to feel the beauty of the movement and to feel the watch on my wrist. However, it didn’t allow me to test the watch properly, to see if the technology deployed was useful. This is why, at the end of my previous article, I ended up saying that ON PAPER, this watch had all the arguments to be extremely precise – and here, you could easily see a sort of invitation to the test we have today. Luckily, the head of movement design at Arnold & Son and the man behind the development of this tourbillon, Sebastien Chaulmontet, is both a good friend of Monochrome (don’t worry, we are still completely impartiality) and someone who stands for his products. He was so good to allow us to put his watch to the test. So here we are, with a 200k watch in the hands, in front of a Witschi testing device and a professional watchmaker (someone independent, not in Switzerland, extremely knowledgeable and not linked in any ways to Arnold & Son or Monochrome).

The technology deployed in the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon

In this video, you can easily see the 3 different elements that compose the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon. These 3 devices are the basics of the entire movement of this watch – all of them are linked by gears and wheels of course but these 3 properly define the concept of this constant force tourbillon. What do we have, and why are they here:

- A double barrel (in series)

The Arnold and Son Constant Force Tourbillon isn’t equipped with one but two main springs, which you are located on the upper half of the dial. Why two of them? First of all, the simplest explanation would be the longer power reserve. Indeed, this watch offers 90 hours of energy; a good result but not exceptional either. The point of having two barrels in this watch is not here. To understand why, we have to go back to basic rules. The energy of a watch is delivered by a spring, wound around a barrel and, when unwinding, it provides energy to the escapement. However, a spring tends to deliver more torque when fully wound than when almost unwound. This issue gets even worse with larger springs. The larger the spring, the more unsteady the delivery of torque is. To compensate this problem, watchmakers who look for a longer power reserve tend to use two smaller main springs rather than one large. This double main spring will help the work of this remontoire by already smoothing the torque over the entire power reserve.

Then, this watch has 2 barrels that are working in series and not in parallel. A first main spring will unwound and deliver its torque. Once about to stop, the second main spring will take over and deliver its torque until the end of the power reserve. This will minimize the torque delivered to the gear train and thus the frictions. This is the first element to participate to the accuracy of this watch: a rather long power reserve, but delivered in a more stable way.

- A Tourbillon

The tourbillon is a specific type of escapement developed during the end of the 18th century and patented by Abraham Louis Breguet in 1801. At that time, marine chronometers, clocks and pocket watches had the same issue: they were worn or placed in static position – on a desk, on the deck of a ship, in a pocket (usually placed vertically). The main issue was gravity. The rate of watches was negatively influenced by the Earth’s gravitational force, in particular the balance whose oscillations were fundamental to the accuracy of the movement. In order to prevent such fluctuations, Abraham-Louis Breguet had the idea to enclose the regulating organ of the watch (the balance, balance spring and escapement) in a tiny cage rotating on itself and typically completing a revolution in one minute. This allows the regulating organ to successively adopt all vertical positions, thanks to which errors of rate cancel each other out.

Even if the utility of a tourbillon is nowadays more than debatable – our timepieces are wristwatches, thus worn in multiple positions – the tourbillon remains a useful device when looking for the highest chronometric results. Furthermore, some of us have a desk activity and our watches usually lay on a nightstand or in a box during the night, and are thus in static positions. The Arnold and Son Constant Force Tourbillon is equipped with a one-minute tourbillon, which is also quite specific in its construction. The balance is not made from a full circle of metal but instead takes the shape of two arches (a Z-shaped balance), to make the balance wheel lighter, more aerodynamic and more balanced. This has of course minor influence but then again, all these small details show the intense work done by Arnold and Son.

- A Remontoire / constant force device

In a recent technical article, our editor Xavier explained to you the ins-and-outs of energy management in a watch. There are multiple ways to obtain a constant (let’s agree on “extremely stable”) force: fusée-and-chain, constant force escapements, an intense work on barrels… For the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon, we have a device dear to FP Journe, the remontoire. Usually, the escapement is linked directly to the barrel by the gear train. Here, in the middle of the gear train, we have an intermediate device, which will stabilize the torque provided by the barrels to the escapement.

To understand why such a device, we have to understand how a watch works. a watch is powered by the torque of the springs. However, we’ve seen that springs are not stable. They tend to give more energy when fully wound and almost none when close to be unwound. This has a direct effect on the amplitude of the balance wheel, which can easily go from 320 degrees to 200 degrees in a normal watch. And of course, this is bad for accuracy. This is why watches with long power reserve are usually regulated in the maximum wound position and this is why it’s not good to use a watch with 7 or 8 days power reserve when almost unwound (accuracy will be poor).

The solution chosen by Arnold & Son in the Constant Force Tourbillon is a remontoire. This is a small spring, which is being charge during one second and that releases its energy directly to the escapement. This remontoire will always release the same amount of energy, no matter if the main spring is fully loaded and has a lot of torque, or whether the main spring is almost unwound. When the power from the mainspring drops below what is required to charge the small spring of the constant force mechanism, the movement stops rather than running at lower precision. On paper, a watch with remontoire will always run on the same amount of torque and will thus have the same amplitude at full-winding or close to stop.

The results of the chronometrie test

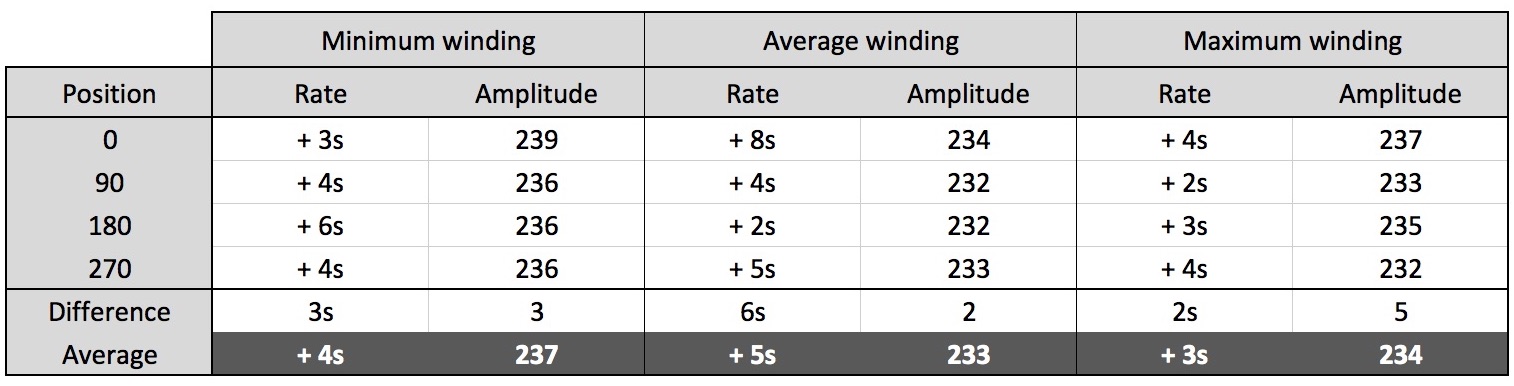

Conditions of the test: The watch has been sent to us by Arnold & Son as a review watch, and, like most review watches, it has been used and abused by several journalists before us. It was not specifically regulated for a chronometrie test or anything like that. We have to consider the ‘risk’ that Sebastien takes, with an unprepared watch, and knowing that this watch is his “baby”; a watch that he, as watch developer, always wanted to create. I brought the watch, with the main spring being unwound, to an independent watchmaker (someone who does services and restoration of antique repeaters, Lange or Breguet, vintage Rolex or Omega… Someone who knows his job – named Alain Delepine). The watch has been tested on a professional Witschi measuring instrument, in the same temperature, humidity and pressure conditions, in one forenoon. The Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon has been tested to 3 stages of its power reserve (at the lowest possible, when the watch just started – at an average position of the power reserve – at the maximum winding position) and in 4 positions. Two main aspects have been tested: the rate (the deviation in seconds per day) and the amplitude (the degrees of rotation the balance wheel does in one beat).

As said, the watch we had was a review piece. It has not been prepared for a specific chronometrie contest. However, if the rate is not perfect (really, we’re pushy…), the results are still properly impressive. First of all, this watch could easily pass the COSC certification (reminder – COSC says -4/+6 seconds deviation per day) and here, whatever the winding, we’re always in the standards of a chronometer (and this is not the case in COSC certification, where watches are not tested in low power reserve conditions). Point 1: this watch is very precise, whatever the winding. This is due to the combo double barrel / remontoire. If we put the average results apart, we can notice that the difference in rate between the positions is low. Here, we have the effect of the tourbillon. Point 2: whatever the position, precision is kept.

The second point – and the major one in fact – concerns the amplitude. At first, I was quite surprised to see such a low amplitude. Usually, watches with normal movements (ETA, Rolex, Omega, tourbillon or not, high-end or entry-level) have an amplitude of over 300 degrees when fully wound. Here, we have only 235 degrees on average. This has been explained to me by Sebastien Chaulmontet:

In a normal watch, when fully wound, you usually have an amplitude of over 300 degrees. Then, when the barrel unwinds, the amplitude gets lower, as torque decreases. The amplitude is always regulated to such a high level because, once starting to unwind, you don’t want the movement to go under the 180-200 degrees barrier (where the accuracy becomes really poor). These 300 degrees or more are only required to provide a correct average amplitude (after 24 and 48 hours).

In the Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon, there’s no need to go that high in amplitude, simply because there’s a remontoire. It is known that an amplitude between 230 and 250 degrees is perfect for the good run of a watch. This is why we have this result here. (Ps. if the final client wants more amplitude, for any reason, this is easily done by just adjusting the remontoire… but useless).

So back on the amplitude results. If we look at the 3 average results, we can see that all 3 are extremely close (and when I mean extremely, it’s an understatement). Whatever the winding stage of the watch, the amplitude is always around 235 degrees. There is a variation of only 4 degrees when a normal watch would show here a difference of maybe 100 degrees. Then, when looked in details, whatever the position, the amplitude stays close to these 235 degrees too, and again whatever the winding. This shows the combined work of the remontoire and the tourbillon. Point 3: this watch keeps the same accuracy and the same amplitude, whatever the winding and whatever the position. I should have taken a photo of my watchmaker when looking at the results. I quote him “I’ve never seen such amplitude results in my entire career, it’s just stunning“.

Is there a utility to this Constant Force Tourbillon?

I think the results of the test talk for themselves. Yes, this Arnold & Son Constant Force Tourbillon has a superior precision and yes, it does really have a constant amplitude – and it deserves the name “constant force”. For those who were doubtful about remontoires or tourbillons, we can see here the effects. Does it mean that a normal watch can’t be precise? No, of course they can. But it will never be that stable over the whole range of the power reserve and there will be higher differences depending on the position of the watch. This piece is made for chronometrie contests, for those who really know a lot about watchmaking – or for the accuracy maniacs. This watch does in real life what it announces on paper. It works, period!

Then again, the point of this article was to demonstrate the effects of constant force and superior mechanics. We’re not going to debate visuals or design, but if you want more, please read our previous review here. More details on ArnoldandSon.com.

Special greetings to Sebastien Chaulmontet (Arnold & Son) for playing the game of this test (he’s one of the fews) and to Alain, watchmaker, for carrying with us the tests.

4 responses

Really enjoy these more technical articles, thanks for them!

Fantastic article! This is an example of someone (A&S) who truly understands horology. Thanks Brice, please do more of the same, would love to see this against a GP Constant Force.

Great article. The watch is truely a work of art.

Watchmaking is both art and engineering, and Goulard has conveyed both very well here. Well done! (I’ll also share that while A&S’s commitment to accuracy is admirable, my ETA 2895-2 powered Hamilton Frogman is faithfully keeping about +1s-2s a day…here’s to Swiss movements!)