A Week in Japan with Grand Seiko Reveals Secrets of the Brand’s Unique Craftsmanship

Trying to understand the Japaneseness of a high-end watchmaker and its unique approach.

Stating that Grand Seiko is Japanese is like saying that the Eiffel Tower belongs to Paris. It seems so obvious at first that you might forget that France’s most famous monument wasn’t meant to become a permanent fixture. With Grand Seiko, the Japaneseness of the brand isn’t just about the location. It’s not about making watches in Japan; it’s about making watches the Japanese way, something the brand calls Dou (?) or The Way. A couple of months ago, I had the opportunity to spend a week in Japan and my goal was, besides visiting several key locations for the brand, to understand what makes Grand Seiko unique. To discover what makes it intrinsically, deeply, brilliantly Japanese.

When I received an invitation from Grand Seiko in the late summer to finally visit Japan and the brand’s manufactures and other important locations (I say finally because this trip was initially planned for spring 2020…), I couldn’t hide a certain excitement. I had long wanted to visit Japan, a country that felt distant to me, a country that I looked at with the eyes of a Westerner, full of preconceptions. I tend to romanticise these things, a tendency that could easily lead to disappointment. Reality can strike hard sometimes. In this case, it certainly did, but not in the way I expected. Being able to travel to Japan has been, for many reasons, a unique experience and might well be why Grand Seiko named this trip the “Grand Seiko Media Experience”.

If I had to summarize the entire week in one word, it would be contrasts. You can see contrasts in all areas of daily life in Japan. The contrast between modernity – an omnipresent overdose of technology – and yet a deep respect for tradition. The contrast between a strong pop culture and underground scene and a profound appreciation for rules and order. This ambivalence is perfectly exemplified when you exit Meiji-jing?, one of Tokyo’s most famous and traditional Shinto shrines, and immediately find yourself deep into Shibuya, one of Tokyo’s most popular nightlife areas.

These contrasts, this constant ambivalence, this is what defines Japan. It has its own culture, its own way of doing things, its own way of looking at every aspect of life. It might be the long isolation of the country, but despite its need to open to the world, Japan remains a place like no other. What surprised me, even more, is that Grand Seiko, in all areas of its watchmaking, from the initial input behind the creation of a watch to the design process and, finally, the manufacturing capacities, is also a world of unique and fascinating contrasts.

From the “House of Precision” to Grand Seiko

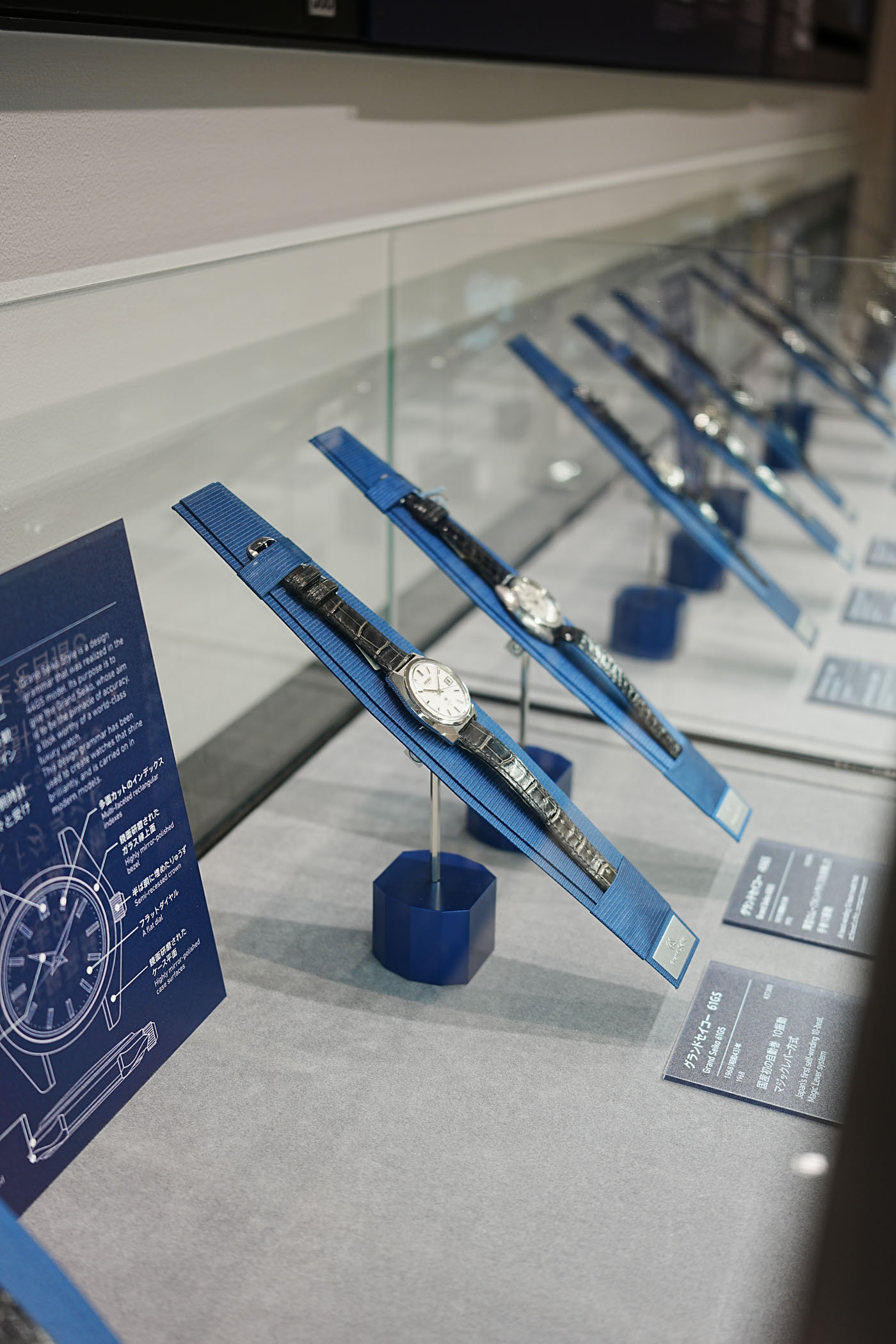

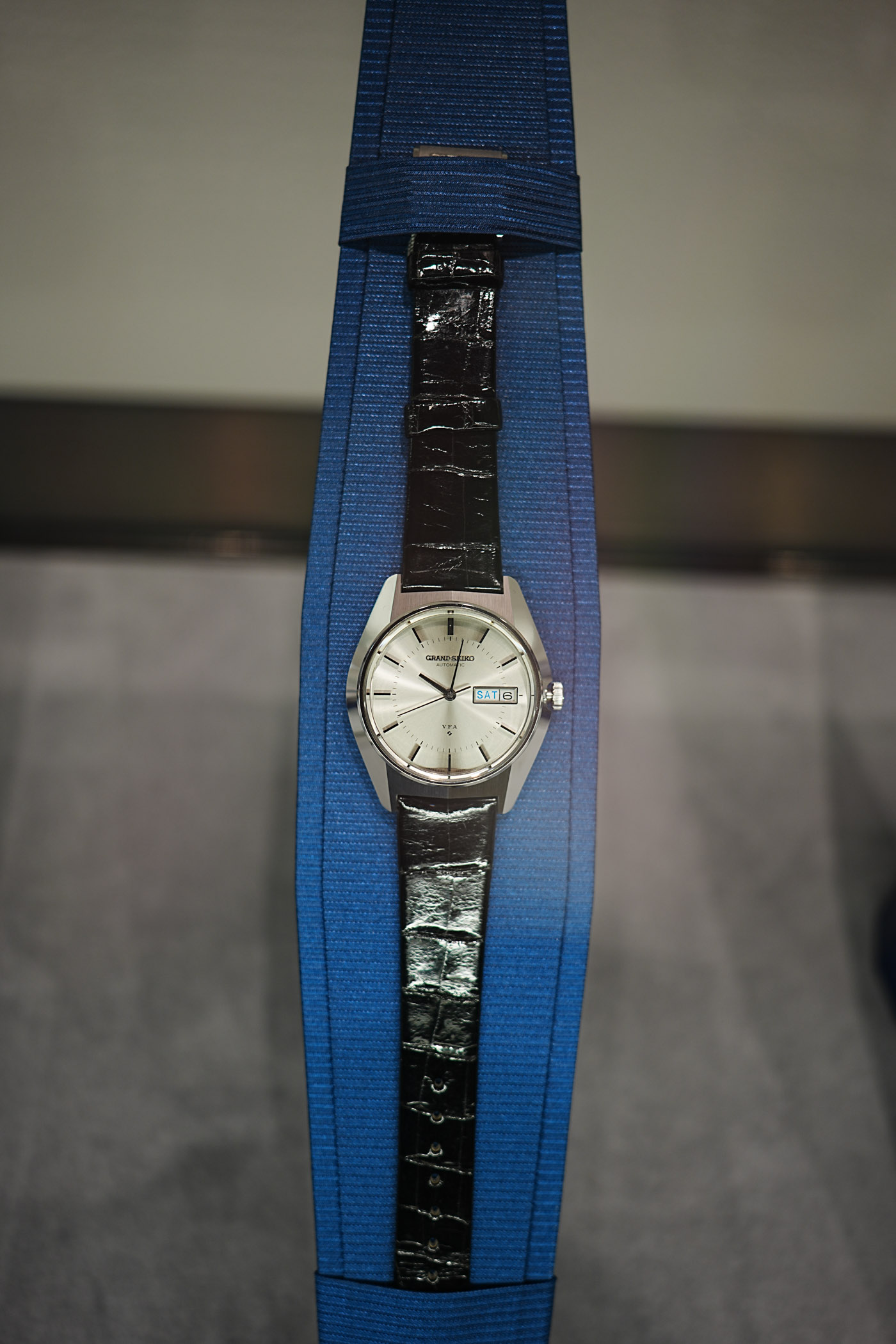

Our journey into the world of Grand Seiko starts in Ginza, Tokyo’s upscale shopping area, but also the birthplace of Seiko, with a visit to the Seiko Museum. It is an impressive place – highly recommendable – with a collection of over 10,000 timing instruments showing the evolution of watchmaking in Japan and the birth and growth of Seiko and Grand Seiko over the years.

To understand the birth of Seiko, or should I say the House of Precision that is Seikosha – seik? (precision), sha (house) – you first have to remember that, for centuries, Japan didn’t use the same timing system as Western countries. Relying on the lunar calendar, Japanese timekeeping was built around divisions between sunrise and sunset – six divisions between sunrise and sunset, six more divisions between sunset and sunrise – but with varying seasons, these units were of different lengths. For this reason, up until the Meiji Restoration, the country relied on wadokei ((???), clocks measuring traditional Japanese time. With the restoration and the move to the solar calendar in 1873, the need for new watchmaking expertise grew.

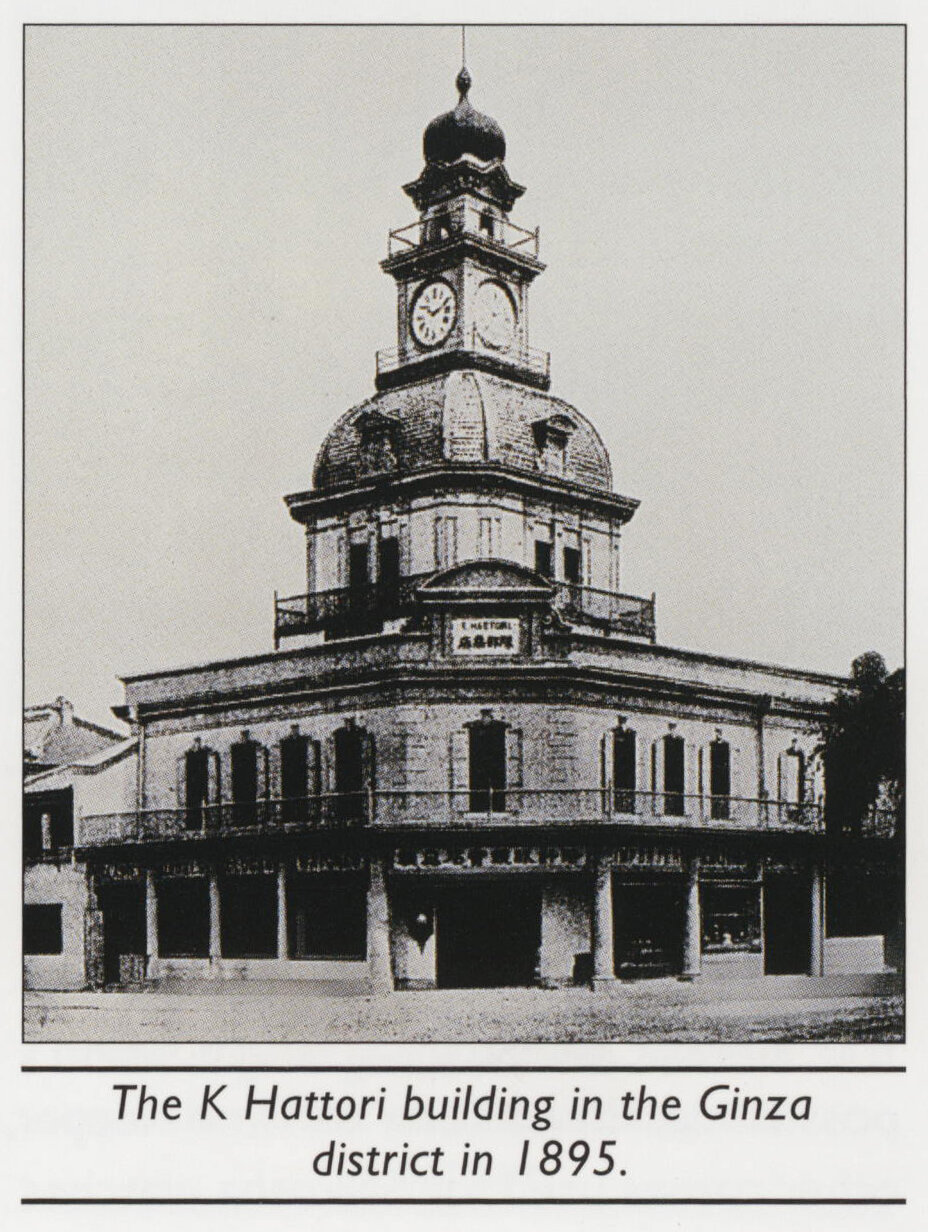

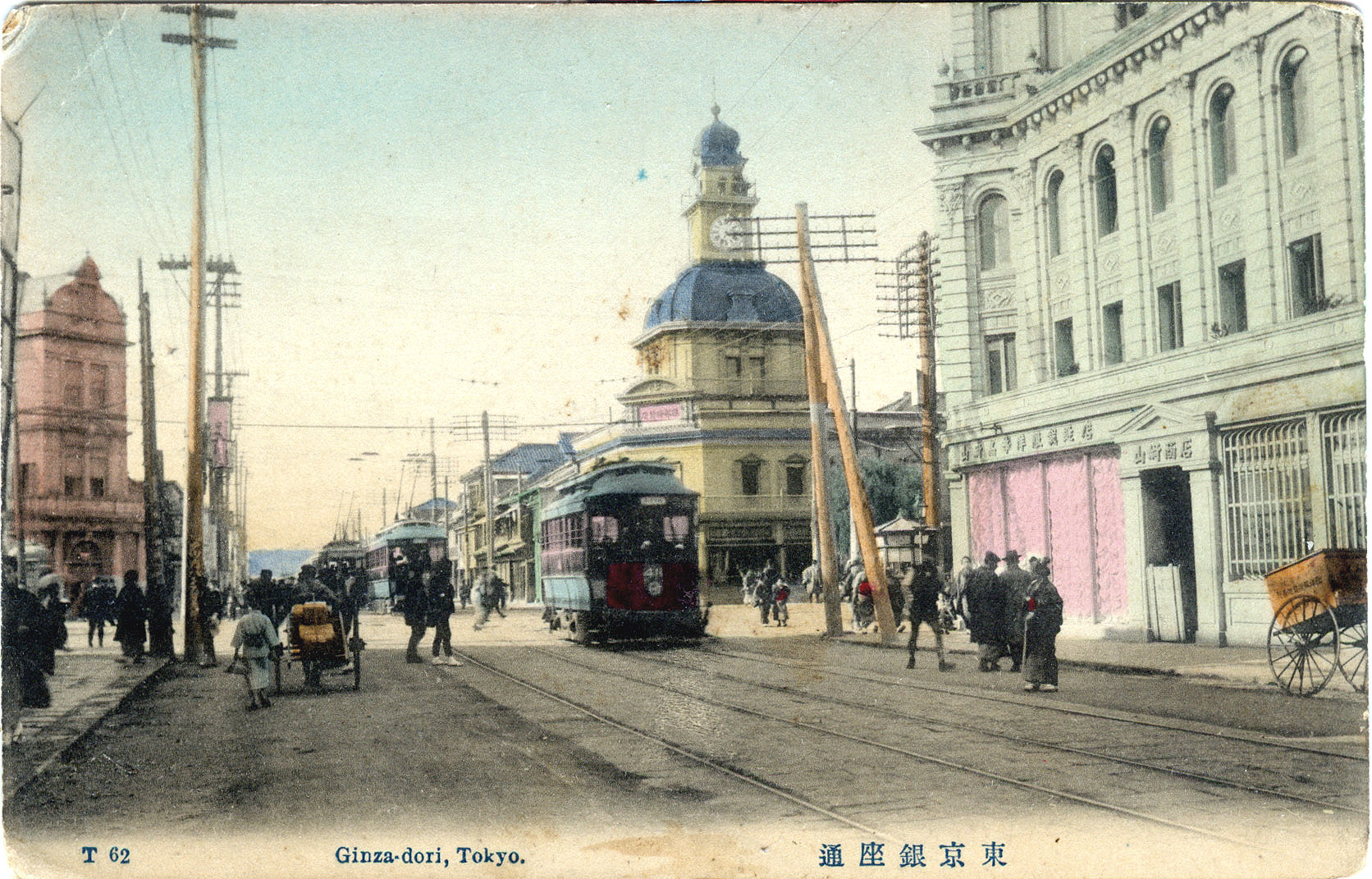

Everything was about to change with the arrival of Kintaro Hattori. Just 21 years old in 1881, Hattori opened his workshop in the district of Ginza, where he sold and repaired clocks. A few years later, taking over a disused factory in Tokyo, he built his own watch factory, which would be named Seikosha – later to become Seiko. In 1892, the first watches were produced, in 1913 the first wristwatch of the brand left the factory and in 1924, the name Seiko first appeared on a dial.

By 1895, just three years after the foundation of Seikosha, the company was exporting, and by 1911, Seikosha had cornered 60% of the domestic market. But things were not as easy as they seemed. Even though the country was undergoing rapid growth and industrialization, Japan’s isolation was still strong. Machinery eventually began to replace manpower at Seikosha. Following visits to the West, Hattori returned with powerful steam engines and state-of-the-art machine tools. Expertise and production capacities had to be sourced from Europe and America. And this is something you can appreciate by looking at the early watches of the brand. The contrast starts here. A deep Japanese culture, heavily influenced by the West – the same can be said for Japan as a whole, which, at that time, had to face immense pressure from Westerners in order to adapt to the rest of the world. The Great Earthquake of 1923 also had a huge impact on Japan and destroyed Seiko’s company building in Ginza. In true Japanese spirit, Hattori counted his losses and, in four days, started to rebuild the manufacture. By December 1924, Seikosha had been rebuilt. By 1932, the Clock Tower, which sits atop the Wako building and is the emblem of the district, was completed.

An anecdote from the Museum, which led to a long conversation with one of the curators… I discovered a small wristwatch from the late 1930s, with a case resembling that of a Calatrava and a sector dial that would have been perfect with the name Longines or Patek printed instead of Seikosha Precision (I must also admit I pushed the idea of a re-edition to the Seiko team). What I want to highlight here is the contrast between what has always felt like a deeply Japanese brand and a production that was still heavily influenced by external factors.

It wasn’t until after WWII that one can appreciate the change in design and spirit. Watches such as the Marvel, the King Seiko, the Cronos or the Gyro-Marvel paved the way for the creation of Grand Seiko in 1960. The first watch to bear this name was still relatively conventional design-wise. Everything changed in 1967 with the celebrated 44GS and the creation of the Grand Seiko Style, a.k.a Grammar of Design. From there, Grand Seiko started to infuse its watches with pure Japaneseness, something that covered every aspect of the watch, from its design, precision and legibility to its unique way of playing with the light.

From there, Dou (?) or The Way became an obsession that can be felt across the board, from the manufacturing to the final product on the wrist. But things were not initially easy for Grand Seiko. Up until 2010, Grand Seiko was (almost) uniquely available in its domestic market. In 2010, Shinji Hattori, a great-grandson of Seiko founder Kintaro Hattori, decided to open Grand Seiko to the rest of the world. Aware of the need for Grand Seiko to stand apart from its more accessible and functional brother Seiko, in 2017, Grand Seiko became a stand-alone brand and, since then, has gained impressive visibility and popularity. Not to mention that, in a highly controlled way, Grand Seiko watches have never felt as unique, as different, as Japanese as they’ve ever been before.

But how are these watches made? The first experience with the manufacturing of a Grand Seiko watch was clearly not what I expected; as I mentioned, I began my journey with many preconceptions. Inside the Wako building is the Atelier Ginza… Not a place where you’d expect to see watchmakers at work. Nevertheless, there you’ll find a small room, one of two locations for ultra-high-end watchmaking. This place was created specifically for the final assembly and finishing of the Grand Seiko Kodo Tourbillon, under the lead of a Swiss-trained rock-star watchmaker named Takuma Kawauchiya (a musician turned watchmaker, obsessed with the beating sound of a movement). And this place couldn’t be more different from the rest of the experience. This is the crown’s jewel, which combines traditional Japanese watchmaking and techniques with postures and processes from the West. However, my next encounter drastically changed this initial perception.

First Stop, Seiko Epson Shiojiri, the temple of quartz and spring drive

Heading west in the mountains next to Nagano is a very important place for Seiko and Grand Seiko, the Seiko Epson Shiojiri Plant. Home to about 600 employees, the initial view is that of an industrial plant, a large white building that could have easily been producing pharmaceutical products or chemicals. And, to a certain extent, this isn’t entirely wrong… Compared to the Atelier Ginza, the contrast was striking.

And yet, the more you dive into this building, the more you feel these contrasts. As I said, an overwhelming sensation of ambivalence… This place is where all quartz and Spring Drive movements (9F and 9R, respectively) are produced. But not only. It is also where the watches around these movements are almost entirely produced, and it is home to the Shinshu Watch Studio, entirely dedicated to Grand Seiko watches, and finally to the Micro-Artist Studio.

This place, once again, oozes contrasts. It is at the intersection of traditional craftsmanship and pioneering technology. One side of the Shiojiri plant is, as you’d expect, dedicated to the manufacturing of parts – all sorts of parts, from movement blanks to raw cases and electronic components. Highly industrialized locations were not part of the visit. However, when I said that there was a connection with chemicals, it wasn’t so far-fetched and can be seen when you hold a MASSIVE quartz crystal grown in-house by Seiko. This, among many other aspects of this manufacture, shows the dedication of the group to be as independent as possible. Or is it the result of the long isolation that forced Seiko to act this way? The President of Seiko Watch Corporation, Akio Naito, told me that the absence of external suppliers resulted in this strategy of vertical integration.

Moving further into the Seiko Epson Shiojiri Plant, you end up in the Shinshu Watch Studio. There, things change drastically from what the exterior of the building insinuates. This is where the distinction between Seiko and Grand Seiko truly crystalizes. Here, cases are finished by hand using the Zaratsu and hairline finishing techniques that I have not seen anywhere in Switzerland (and I have seen more manufacturers than I care to admit!). Hand craftsmanship is everywhere, with a tangible dedication from the women and men working on these watches. It’s still a rather oil-filled place, but you can see the attention to detail. Employees entrusted with this task can use only their eyes and the feeling in their fingertips to sense the exact angle and pressure required. Then, and only then, will the famous distortion-free mirror-polished surfaces appear.

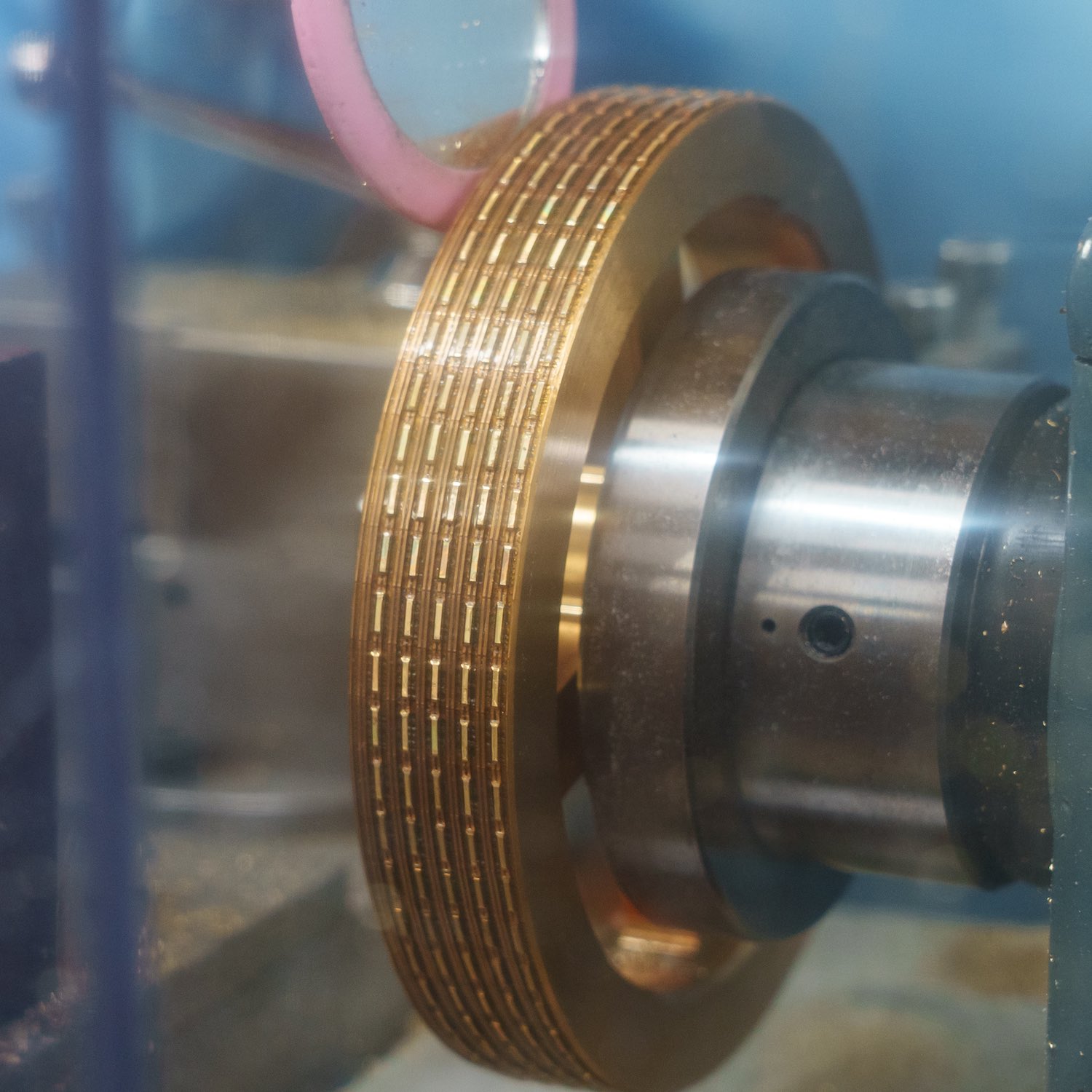

Grand Seiko is rightfully proud of its dials, and these are also crafted in this studio (at least, those used on 9R and 9F watches), using textures that reflect the “Nature of Time” philosophy of the brand. The Japanese attention to detail becomes clear when you see how the markers of these watches are done. Once again, a technique that I’ve never seen before. There are no CNC machines or computer-controlled diamond-cutting tools here; instead, the markers are cut and polished by hand using a rotating drum – I’m still wondering exactly how it works, but I’ll leave this as part of the mystery.

Assembly, adjusting and control take place in a series of ateliers that are surprisingly different from Swiss or German manufactures. First and foremost, the posture. Japanese watchmakers work using a microscope, not a loupe. It is a detail, but one that has its importance in the overall philosophy of Grand Seiko. It reflects a different way of thinking.

The Shinshu Watch Studio is also home to the Micro Artist Studio, the second jewel of the brand, where high-end Grand Seiko and Credor watches are built. The contrast with the rest of the plant is once again striking. There, time beats differently, slowly, peacefully. There, Philippe Dufour has a caring eye on things. There, watches are more than timekeepers. They are objects of true Japanese art, mastered by highly skilled watchmakers who have been trained internally at the Takumi Studio. Indeed, in Japan, you’re not a master watchmaker; you’re becoming a Takumi (?), something that has long been recognized by the government and that is cherished by Grand Seiko.

There, you can be selected by the Japanese government as a Contemporary Master Craftsman and awarded the Yellow Ribbon Medal given to individuals who have become public role models through their dedication to their work. This, when compared to the technology deployed in a Spring Drive movement, is what best represents to me the concept of Japaneseness, the clash of cultures that results in an object where perfection is constantly sought.

Stop two, Mechanical at Grand Seiko Studio Shizukuishi

The second half of this experience leads us to the north of Honshu, Japan’s main island, in a quiet forest in Iwate Prefecture near Mt. Iwate, one of the country’s most famous yet shy mountains. We’re far from Tokyo and its bright lights. The main building that composes the Grand Seiko Studio Shizukuishi is yet another shock, strongly contrasting with what was behind us, the Shinshu Watch Studio.

Here, mechanical watches are manufactured. And not only movements. Entire watches. Next to this immaculate, serene wooden building are yet more industrial plants where raw parts are produced. Indeed, as surprising as it may sound, cases, dials and other external components of mechanical watches are produced here, too. Production capacities are doubled at Studio Shizukuishi. This explains why, for instance, small differences can be seen between the Spring Drive watches and the mechanical watches that form the Grand Seiko 4 Seasons Collection.

There’s a tangible serenity in this place, a connection with nature that was key in its conception and that has been around since its opening in 2020. Nature surrounds the place, almost invading it. In a way, this contrast between what remains an industrial activity and this place exudes the same feelings as the perception most of us have of mechanical versus Spring Drive or Quartz watches. Despite many of them having a hi-beat movement, mechanical watches run at a much slower beat than quartz-controlled watches. In a way, it’s ancient, traditional watchmaking versus innovation and technological mastery. Like the rest of Japan, contrasts are everywhere.

Once again, time flies differently in this place. It’s a modern manufacture, designed to be an example of what the country is capable of. And yet, it remains deeply imbued with traditions rooted in its location and its surroundings. But it’s also a place where people have conceived highly advanced movements, such as the Calibre 9SA5 and its Dual Impulse Escapement. The rush to always do better is inevitable; the idea to constantly improve is inherent to Grand Seiko, and yet, time seems to have stopped near Morioka.

The moment arrives when you strap a watch around your wrist, the Grand Seiko Studio Shizukuishi behind you, maple trees that have turned red with the Autumn on your right, a small garden designed according to Japanese traditions on your left and Mt. Iwate looking at you in the far side. Then, you understand what Japaneseness at Grand Seiko means.

For more details… I would normally invite you to check www.grand-seiko.com, but this time, even to the best of my abilities, I won’t be able to transcribe everything that I’ve seen and felt during this experience. So, instead of clicking on a link, I encourage you to fly to Japan.

9 responses

Sure they have the micro studio and now it is time for micro adjustment in their clasps.

Ok, I had to be that guy and I love GS.

Great story. A very nice read, highlighting the contrasts.

Which model of strap is on the GS SBGM221? It looks great!!

@Rob – it’s a taupe nubuck strap, which we sell in our webshop. You’ll find it here (make sure to take 19/16mm) https://shop.monochrome-watches.com/collections/nubuck-watch-straps/products/monochrome-nubuck-watch-strap-taupe

@Yachtmaster2021 – it is one of the possible improvements I mentioned to them… let’s hope the team at GS considers it.

As a former Japanese resident and longtime admirer of Seiko watches, I thoroughly enjoyed your observations and insights of a brand that has through generations of hard work, dedication to tradition and innovation achieved its definition — success. How ironic that a photo of a worker shows a smart watch on a wrist. Not enough wrists to go around for Seiko timepieces. Thank you.

The story is a real eye opener very well written. The only problem is I did get to go with them ,

!

Thank you Brice.

I have owned a rose gold Eichi II for four years and it will remain the crown of my collections forever.